Years ago I kept a diary. Beginning with my sophomore year in high school, I dutifully recorded my thoughts and the day’s events. This exercise continued after graduation and into my freshman year at the University of Southern California. I took the book with me to London that summer, where I spent a few months with my family. I got to know a fascinating guy there named Michael Wall, whose extraordinary career as a playwright had barely gotten off the ground when brain cancer took him. It was in my pocket when I left for the Bath Rock Festival, a chaotic mess and sublime generational experience. When I got back to home, I dutifully scribbled down every detail,

This archiving stopped when I flew back to my dorm at USC and unpacked. Everything I had taken with me was there, except for the diary. I turned my clothes inside out, looked for rips in the fabric inside the suitcases, inspected every inch of my room. Then I did it again, several times. I called my parents – this wasn’t as cheap and easy as it has become in the Skype / FaceTime / Zoom era – and asked them to hunt for the missing journal at their place. There, too, nothing turned up.

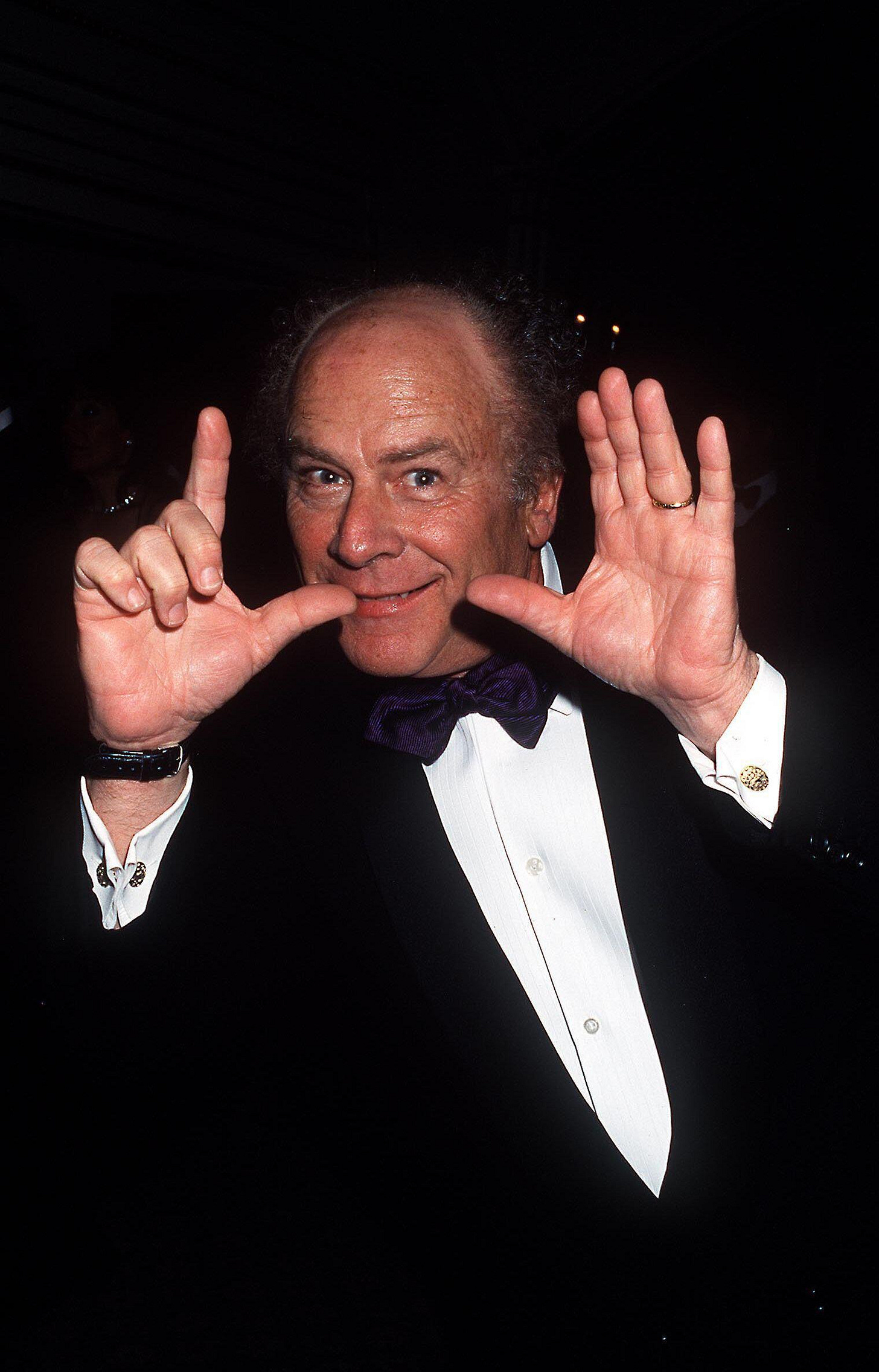

I don’t exaggerate when I say that the next several years, though bristling with memorable diversions, passed with a pall overhead because of this loss. A long time had to pass before I could accept what had happened. Not true, though, as far as my chat with Art Garfunkel, more than half of which for some reason has disappeared, or been erased or what have you.

When I was called to write the PR way back in 2002, the incomparable vocalist had done his first post-Paul Simon collaboration. With Maia Sharp representing the West Coast and Buddy Mondlock in Nashville, Everything Waits to Be Noticed was a true transcontinental project and a bit of a risk. At the time he hadn’t worked with or even heard of either one; nonetheless, for reasons noted below, he agreed to give it a shot. Even more significantly, this album represents the fabled singer’s first attempt at writing. Having worked long with Simon, there was no shortage of great material. But with his former partner testing the waters from South Africa, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, the black church and other ports of call, Garfunkel focused on the music he knew best: introspective songs of love, sung or almost whispered with the clarity and emotional fragility that defined his vocal style.

For the bio I interviewed Maia and Buddy, of course, but Art and his compositional debut were the true heart of the project. I had listened multiple times to advances of Everything Waits to Be Noticed, taking notes, formulating ideas for my questions but also falling more into the album’s misty spell with each play. I was bewitched by one track in particular, “Perfect Moment,” whose dreamy romanticism testified to Garfunkel’s then untapped potential as a melodist and lyricist.

As I recall, we had to reschedule our original date and time to talk because, as Art’s people explained to me, it conflicted with one of his “silent days,” dedicated to resting his voice. When we did connect by phone, he surprised me before I could get to my first question by asking if he could read to me a mini-essay he had written and hoped could be included in the final edit. Naturally, I invited him to continue and sat back to see where his ideas would take me. His essay begins the transcript, indicated by quotation marks.

****

“How it began. It was the end of a thousand years. Late in ’99 Billy Mann, this amusing longhair, was pitching me to produce my next recording. I was hard to get. Billy called from London. He had just written “Bounce” with Graham Lyle and he played it on the phone. It was irresistible. He said, ‘They wrote it for me.’ And they knew of two great talents that he envisioned singing and writing with me. I told him I wasn’t a songwriter but that the prose poems I’d written …”

… because you know, Bob, I put about 84 prose poems into a book that had gotten published with the title Still Water.

“ … but that the prose poems I’d written might, some of them, be halfway to being songs. Three weeks later he invited me to Nashville to hear what Buddy Mondlock had written to my words. And so, at the turn of the Millennium, I heard my words come back to me in the song ‘Perfect Moment.’ Buddy was right on my wavelength. Billy was a visionary, it seemed.

“Maia Sharp flew in the next day. She brought her saxophone and this great, hip singing voice. So we all wrote ‘Wishbone’ and demoed the three tunes in Nashville that snowy January. I was the host on Saturday Night Live that week — a replay — and Maia tried to Polaroid my face alongside me on TV while Herb Tassin and Billy mixed our songs in the control room. The Tennessee Titans were headed to the Super Bowl. Bill Clinton’s State of the Union address made us all feel good that week, when I became a songwriter.”

You see, when Billy Mann showed me “Bounce” from London, which he’d written with Graham Lyle, I did love it. It made me feel that Billy is studio-savvy. This guy produces beautifully. These are hooky rock ’n’ roll things. I love the simplicity. It’s not ponderous at all. It’s not a crafty, arty rock ’n’ roll record. It’s a catchy rock ’n’ roll record. I loved it for me. So I was halfway home, even though I’m a hard sell.

I believe I mentioned to Billy, “I wrote a lot of things. they’re not songs. They’re prose things. But if they could be made to be songs, you would have locked up my account.” In other words, “You’ve got me, if you can do that.” That would be such a big thing in my life, that many of those things that I wrote are able to be turned into songs.

Was the poem also titled “Perfect Moment”?

The poem has no title. None of those poems have titles.

As you wrote that poem, was there even a hint of music in your head?

No, there wasn’t. I don’t know if Billy mentioned that to Buddy. He probably did. He said, “I know Art would be tremendously impressed to see any of this stuff in the book Still Water.” Maybe Buddy went out and got it.

How altered was the text when you heard it set to music?

Oh, something like fifty percent. You have to hear it and then you have to read it.

Not beyond recognition or beyond your intent when you wrote it, though.

That’s a very good point. What killed me is that the intent, the feeling, is the same thing that infuses the song. It’s as if the kernel and the heat is the same as the song. That’s why I love it. Every time that I do it onstage, it’s partially mine in its lyrics, partially Buddy’s and Pierce Pettit’s, the other writer.

Can you point to an example of how something you wrote in that particular poem might have been varied somewhat to fit the demands of melody or music?

“A wishbone was broken. I’m left holding the smaller part.” I watched Maia and Buddy take things that I’d written and use phrases out of them. Songs are often a lot about good phrases, so they sort of tore apart my song and used phrases.

On “Wishbone” the line “I wish to God you were still alive” stood out to me because of its directness and passion. Was that lifted intact from your original poem?

Not at all.

Maybe the fact that it stood out suggested to me that it had been added during the process of writing the music.

That’s right. it’s a bit of a stab, a breakout. That’s something that my writers put into my mouth.

How long have you and Billy known each other?

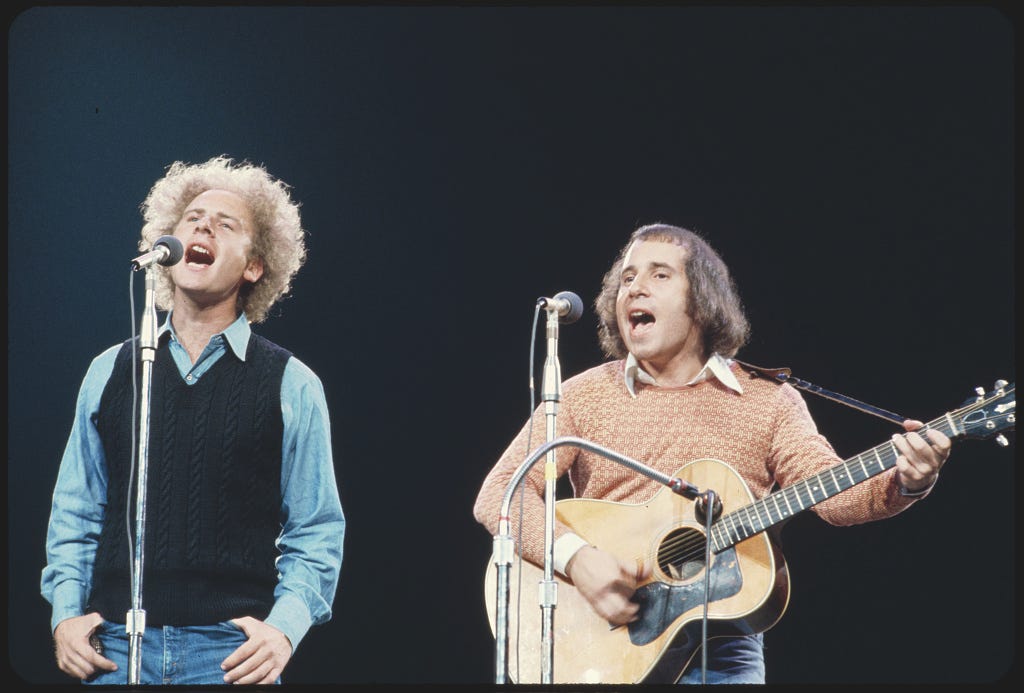

There’s only so much I know from impression. Then comes the focus of, “There he is. Now I know.” He had an interest in me as an artist that he understood. From what I understand, he goes way back to knowing my voice from my Simon & Garfunkel days. I met his mom and she said, “I played a lot of your Bookends album when I was carrying Billy in the womb [laughs].”

So I thought Billy had a real special ear for my half of Simon & Garfunkel. He was sympathetic to my whole thing. He knows that I’m understated about my talents, so he was trying to compensate for that. He became a good advocate for my career.

He tried to get to me through Rob Kos, my working manager at the office. I finally met him when I took a meeting. When Billy left, I thought, “I like his style and his look. He’s very healthy — looks like a firstborn. He looked like he got a lot of love from his parents. This is a very good-hearted Francis Ford Coppola of a guy.

Being raised on your music couldn’t have hurt.

[Laughs.] He had a nice, peaceful, energetic, very positive kind of post-hippie, spiritual hipness about him. I like Billy a lot. I thought, when he left, “He does everything right. He knows the record business. He says it all perfectly. But of course, words are words. How would it really be to work with him?”

He left me, knowing that he had intrigued me but I wasn’t committed until he called shortly after that. He had written “Bounce” for the Ben Affleck movie with Gwyneth Paltrow (also titled Bounce). They wanted me and the trio to be the singers. He played it on the phone for me in London. And I adored it. Then I said, “If you can get some of my poems turned into songs, you will have really changed my life. I will be more than interested.”

He’s the rarest of people: He heard me and he did it with Buddy Mondlock.

Were you familiar with either Buddy or Maia before this project began?

No, I wasn’t. It was all Billy. Once Billy said, “Come down to Nashville and you’ll hear what we’re working on.” I took the leap of faith: We were going to write together and record together. We already had “Bounce.” So I came down and Billy played psychiatrist. I was the patient and he was the psychoanalyst. He broke me down into a nice attitude of trial and error. He introduced me to Buddy Mondlock. Buddy showed me the song — he had a very spare acoustic guitar style. I began to see these wonderful chordal things — the minimum number of notes. So super-spare that if you’re a lover of “less is more,” and I am, Buddy is your guy. He was great for me.

Then he showed me “Perfect Moment.” My own words came back to me and I’ve got to say, Bob, I experienced one of the great moments of my entire being. That was really special. I thought, “Here’s my song. Here’s the heart of the song, the intention of the song, preserved and coming back to me intact with this lovely melody that’s so right up my alley, so much my taste. It was just fabulous how Buddy divined my kernel of a song and finished it off. There was the melody, all theirs, with some dropping of my words and some changing of their words.

Now I come in and I tinker on the final ten percent of the lyric — just a little finesse work, to tighten certain things. Buddy and Billy would keep coming back to me: “Well, what was your intention? Go back to the experience, when this happened to you.” They kept looking as if that’s the fountainhead of source material. I would talk about it and maybe sometimes describe it in a valuable phrase that was nice for us. Things come out of the truth into good songwriter language if you have a good feel for it, and I was developing a feel for that language.

Then we went onto the next song. They said, “Maia Sharp is flying in tomorrow. You’ll love her.” I did. We all sat down at this round table in Nashville, at Bob Doyle’s work complex. Maybe Maia and Buddy came in a little earlier than I did because when I arrived they had been looking at my Still Water book, wondering which poem would they do on this day. And it was “Wishbone.”

How different an experience was it when you began hearing your words come back to you in song? Did that lead you to a process within you that you hadn’t tapped into before?

Well, it has certain similarities to the prose poems I’ve been writing, which is a lot about pacing and pacing. You twirl your hair and do these nervous habits as you hunt and hunt for the syllabification and the right rhyme that says what you want in the most forceful way. …

####

And the rest of it is missing. I don’t know why. I never will. Fortunately, while my lost diary took five or six years of memories with it, only another half hour or so of this transcription is irretrievable. If it’s one of those days when depression seems like an appropriate response to worldly events, I can easily slip into regret about these losses, and others too. But at least the music is still with me, which for us music journalists, is what it’s all about anyway.

###

Another great one Bob - I think any writer not distressed by losing part of their work is maybe not trying that hard...

I don't wish any ill to Artie, at all. Nonetheless:

I think he's pretty modestly talented. He would have been better off, after Simon, finding another singer/songwriter to complement his (undeniably sweet) voice.