I’ve never experienced a longer day than I did after flying to Spain for an interview with the enigmatic Icelandic artist Björk. I’d already spent several days listening to advances of her upcoming album, Homogenic, as well as earlier releases. I’d read other interviews with her, which somehow provided insight while not clarifying much about how she had developed her singular approach to recording and performing.

I landed at the Airport Picasso in Málaga, caught the shuttle down to Marbella’s Costa del Sol Airport and from there drove to my hotel, which was overrun by British weekenders. That night, I visited the bar in hopes of ordering a glass of absinthe, whose history among French and Spanish artists had kindled my interest; though illegal at the time in the U.S., it was still available in Spain. Turns out the Brits had already exhausted the entire supply, so I returned to my room without the benefit of hallucinogenic insights, which I’d hoped might help me see deeper into the mystery of Björk.

The next morning, after a restless night on my room’s single bed, which could easily have seen prior service as an army field cot, I headed back toward Marbella, this time following directions to drummer Trevor Morais’s studio. I can’t describe it any better than I did in the cover story I wrote after my return to New York: “[It] perches high above a swimming pool and a deep, scrub-filled ravine. In the distance, looking south toward the Mediterranean, the sky melts into a watery horizon. A patio, lined with colorful tiles and bordered by Cordovan pillars and arches leads toward the open front door.” This served as both residence and workplace for Björk as she crafted Homogenic.

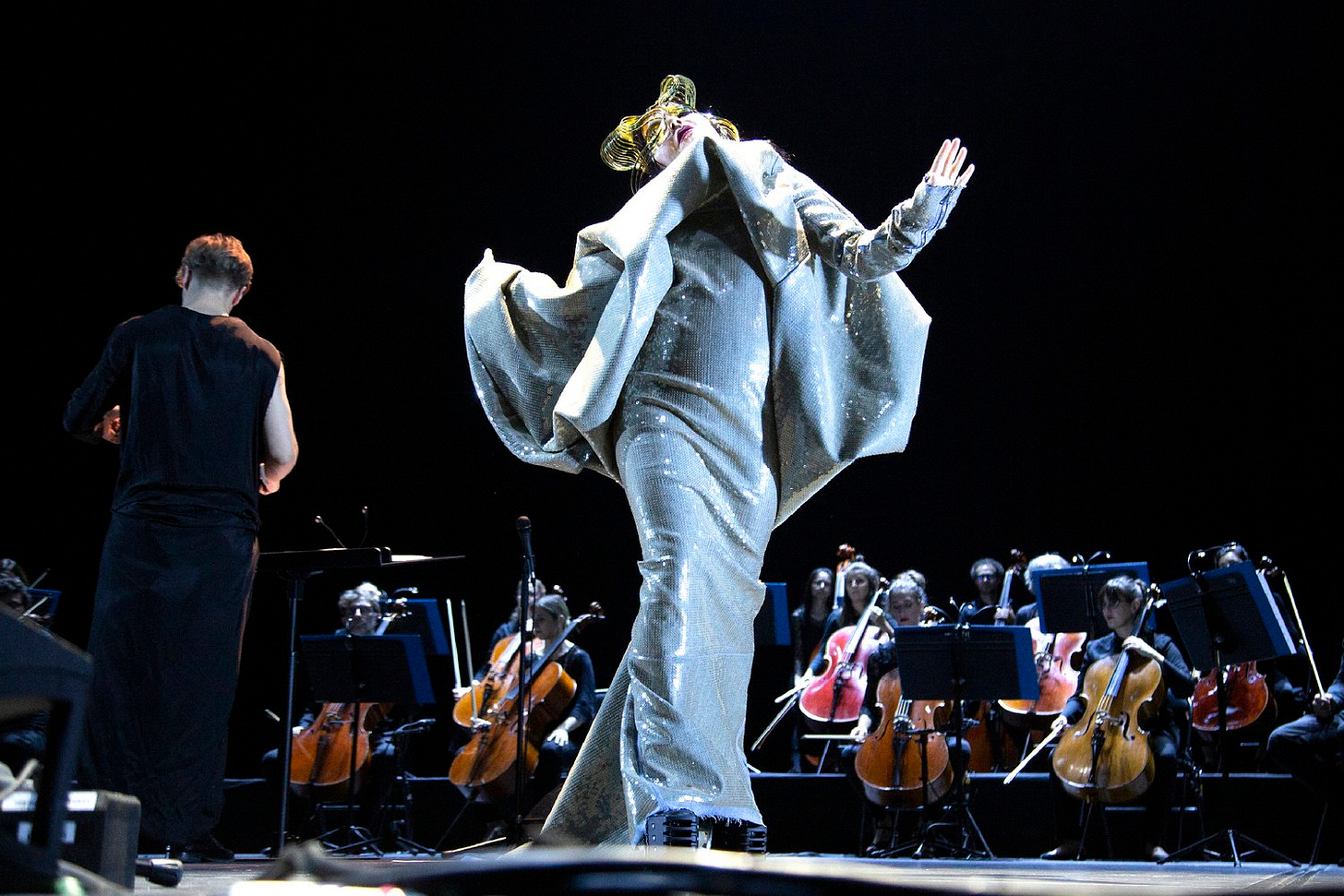

As we met, she was in an exuberantly upbeat mood; clearly, the sessions and the intoxicating sea air were working their magic. There was none of her stage flamboyance in the white slacks and blue short-sleeved shirt she wore. As we spoke, she emanated a pixie energy, frequently laughing, underscoring her stories with playful snorts or animal noises and, it must be said, uninhibitedly and frequently picking her nose and flicking whatever she pulled out from it, grinning as if she’d removed a critical object to her productivity.

We spoke on and off throughout the day, in between hours of working on tracks. During these breaks I would sit with members of her team, including famed Brazilian composer and arranger Eumir Deodato. By around six o’clock we had wrapped the interview and I headed back toward my hotel for what I hoped would be a better night’s rest. About halfway there I noticed a restaurant just off the AP7 coastal highway, where I stopped for dinner. The maître d’ regretted that they had just sold their last bottle of absinthe, so I settled for water.

At the hotel the Brits partied rowdily. English-speaking singers and comedians provided entertainment, barely being heard amid the festive din. The bartender confirmed sadly that once again, they’d run out of the Green Lady. I headed back to my room … where, for whatever reason, I lay absolutely awake until the next morning, when I checked out, retraced the now familiar route up to Málaga and, surrounded by business-garbed commuters, back to Madrid and onward to New York, still maddeningly awake. Somehow, even after my delirium, details of my day with Björk never faded.

After all the diverse influences you’ve incorporated into your music, is Homogenic more of a pure Icelandic expression?

First of all, there is no such thing as Icelandic music. But I want to prove that there should be. Just by looking at the mountains and walking around, you can feel that.

Iceland’s literary history is so rich, though. Why hasn't its music developed as well?

There’ve been many thoughts about that. The Danish treated us very badly for the six or seven hundred years we were their colony. For example, the church banned musical dancing. So storytelling became the thing that thrived with us. Storytelling is us. The Icelandic people, we were the ones who wrote down all the sagas. They memorized stories from generation to generation. They could go on for, like, two hours. That’s why I believe in old-school songwriting. Now, I really respect the Sixties pop culture of the Beatles, where you get one idea and you repeat it nine hundred times. I respect that repetition: “Love, love me do.” But that’s not where I come from.

So that’s where your way with lyrics comes from. What about the music, since Icelandic music was nonexistent?

First, it’s the beats. It’s to prove that techno doesn’t come only from Germany. There should be such a thing as Icelandic techno, which if you look at nature in Iceland, you’d see that it would be very simple, very explosive, very raw. I mean, NASA sends its astronauts there to rehearse, because it’s like a moonscape. So I want the beats like that.

Then the second thing is the strings. I attempted to make string arrangements, with a lot of help from [Brazilian composer Eumir] Deodato. He’s been like a big daddy, letting me experiment with notes but being there for me when I need him and sometimes just completely doing it for me. So the starting point of this album is beats and strings, with the voice in the middle.

Which would be different for you.

Very different. That’s why I call it Homogenic. It’s like a challenge in that you have few tools to work with but you want the whole emotional scale, as before. Some of my favorite albums are just, say, one voice and one drummer, but you’ve got one sad song, one happy song, one intellectual song, one prankster song, just with fewer tools. …

This is very important: People have said that I do a bit of this and a bit of that, but that’s never been the case. I never wanted a style simply for style’s sake. Music is a very personal and human thing, so if I go and do a song with, say, [rap artist] Tricky, I don’t give a shit where he comes from. His race is bollocks. And when I’m talking to you, I’m not looking for your passport and wondering where you’re from or what brought [you] here, like the hippies do: “I wonder what star sign he is.” No luggage, please! When I work with someone, it’s down to [unintelligible] characters. Björk Goes Latin? That wouldn’t be honest.

Yes, but when you recorded, say, your rendition of “Like Someone in Love” [written in 1944 by Jimmy Van Heusen and Johnny Mercer], the arrangement stays within the tradition of American standard tunes. In that sense, you seem to be going away from what might be your natural cultural reference.

[Sighs, a bit frustrated.] We can analyze forever what it’s about, but it’s just an instinct thing. It felt right to do that song, but I had to be respectful as well. Maybe it’s a balance of how much you can visit, like the balance between how much you stay in your house and how much you go to [your] friend’s house for dinner. For “Like Someone in Love,” you can say, “Let’s eat out tonight.” You just can’t do that as much.

“For the first few years I sang, I used no words.”

So what will you be working on today?

We’ll be doing one of the songs that Deodato did the strings for. I haven’t even heard them yet, so I’m very excited about it. [Björk plays the next track on her cassette.] This was the first version. Later we introduced the bass line; it’s so easy to do a song for a bass line, so putting a bass line in at the last stage is like indulging yourself.

Deodato wrote the string charts without knowing what the bass would play?

Yeah [impish grin]. I wanted so much for it to be just beats, strings and voice. [We listen for a few moments; the final version of the song, “Unravel,” is on Homogenic.] There’s a lot of storytelling going on, a lot of brutal, in-your-face stories. One of them is this kind of Wuthering Heights epic. [She puts one hand melodramatically over her heart.] The first song in this epic was “Human Behavior” [from Debut, 1993]. The second one is “Isobel” [from Post, 1995]. I guess this one is the sequel.

Why did you come all the way down here to Spain to do an album that’s so strongly connected to Iceland?

Well, I do go to Iceland. It’s my home and it always will be. But I need to get away from the world as well. Iceland isn’t what it was like when I was a kid, because I’ve become something … different. It’s the same for me, but I’m not the same to them. If I’m gonna fight that one, I’ll spend the rest of my life doing it. It’s better to accept it. There were boring practical reasons too. The fact that I don’t know anyone here in Spain keeps [me] working. It’s also so beautiful here. There’s not many places where I feel at home, and I feel at home here for some strange reason.

Soul Within Soullessness

You studied classical music for ten years, from five to fifteen years old. What was the most important lesson you learned in music school?

The best thing was that it introduced me to all music. Well, actually, that’s not true. That was another thing I learned. “Classical music” is really music from Germany over a period of two to three hundred years. You go to the classical section at Tower Records and it’s German music. That says a lot about the history of humans for two thousand years, because we’ve been making music all this time.

My obsession was always to work with people to create something that had never been created before. That became very obvious in my school. I had a lot of meetings with the headmaster. He would sit there and say, “What are you doing with yourself? You’ve got this talent and you’re just wasting it! You’ve got no concentration!” It was like a love/hate relationship between us. I used to go to his classes, and he tried to make me work. But I’d just sit there and cry my eyes out. I couldn’t fit in the mold. He was Jewish; he escaped from Germany to Iceland just before the war. But I’m Icelandic. I’ve got a voice. And it doesn’t have to be so complicated. It’s just about me and you communicating. That’s my biggest turn-on, to meet someone who comes from a completely different place than I do. I’ll show them everything. I’ll give them everything I’ve got. For me that’s creating: One plus one is three.

You must have had a more eclectic group of influences than most of your fellow students.

If I were to say who influenced me most, I would say people like Stockhausen, Kraftwerk and [recording engineer on Homogenic] Mark Bell. I’d been watching Mark since 1990, when he was doing [early techno band] LFO. The work he did when he was nineteen proved to our generation that pop music is what we understand. We walk around with all these telephones and car alarms. We hear all those noises. We keep saying, “No, it’s soulless. It’s cold.” But it’s part of our lives. Also, I like the pioneers who have stayed faithful to techno.

“There should be such a thing as Icelandic techno.”

You probably weren’t exposed to much electronic music as you were growing up. Did that present any problems in learning to create with those tools?

For anyone to communicate, you have to make an effort. Whether you’re born in Idaho with American TV or in Guatemala, you’ll always have to fight certain barriers to communicate. For the first few years I sang, I used no words. Then very slowly I started throwing one or two Icelandic words in there. When I was eighteen, I did my first tour abroad, and I would translate one or two words into, sing the rest in Icelandic and do noises. Communication is about energy. That’s how we are, and the language sometimes doesn’t matter all that much.

Are your English lyrics literal translations from the original Icelandic?

They’re as literal as they can get. Icelandic is very personal to me. I’ve tried to do interviews like this in Icelandic, but I can’t. I just feel like I’m lying, because English is in the head, being clever, analyzing myself, seeing myself from the outside. Icelandic is personal and private. I still can’t translate certain lyrics because they’re just too intimate.

Do you dream in Icelandic?

It depends on what kind of day I’ve had.