Through most of my life I knew that country music existed but not much more about it than that. Having spent three years in Austin, I was familiar with the so-called “outlaw” movement, most of which was rooted in Texas, and I knew that Nashville was its corporate epicenter. To me, that confirmed the notion that Willie, Waylon, Jerry Jeff and those who flocked to their shows at the Armadillo World HQ were the good guys, uncorrupted and not at all slick like those “countrypolitan” crooners who had dominated the industry for so long. And certainly I had no idea who Bobby Braddock was.

My eyes opened, quick and wide, when Billboard Publications transferred me from New York to Nashville in 1998. Central to my epiphany was to appreciate that more than a recording wonderland and label headquarters, this was a songwriter’s town. The learning process accelerated when I was recruited to edit CMA Close Up Magazine. I began to appreciate how the approach of Music Row publishers differed from what I’d seen in Austin — not songs steeped in political commentary or perspectives that could be unique only to the artist who wrote and performed them, but generic tunes, crafted to be accessible to as many singers as possible. They had to have hooks that stuck with you. They had to celebrate a lifestyle that might be authentic for many though more often represented a kind of fantasy. And they had to be concise enough to make it onto country radio, whose listeners had neither the time nor patience to stay tuned for more than a minute before switching stations.

More importantly, I learned that within this community of hit-making writers was a more select group who understood all these limitations and yet had found ways to come up with songs that did go deeper, lyrics that spoke poetically without losing a vernacular touch, melodies that could coexist with catchy riffs. And probably the most revered among them is Bobby Braddock.

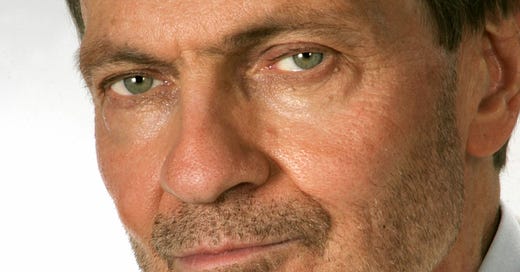

I made Bobby’s acquaintance while at CMA. Before our first interview I studied up on him and learned that, among many other distinctions, his songs had topped the country music charts for five decades, beginning shortly after he left Florida and first set foot on Music Row in the Sixties. Many of these are considered classics now, especially “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” anointed by Radio & Records Magazine as “Country Song of the Century.”

The Bobby Braddock I came to know is quiet, not terribly talkative but amiable and approachable. Above all he has a sly sense of humor, as evidenced in some of his song titles (“I Wanna Talk About Me,” “You Can’t Have Your Kate and Edith Too,” “I Lobster but Never Flounder”). Happily, he also shares my lifelong interest in Civil War history, a topic we discussed once we’d completed this interview.

We met at the office of Sony/ATV, formerly Tree Publishing Company, which has represented his songs since 1965. Bobby was slightly late; his publicist and son-in-law Jim Havey explained to me that he was getting his hair cut in the barber shop he’s patronized for years. “You know how old men are with barber shops,” Jim joked. I laughed, knowing that the wisest among them are treasures that deserve to be revered.

The subject we addressed was the publication of his latest book at the time, A Life On Nashville’s Music Row, but being men of a certain age we let the conversation ramble far beyond that.

###

Why did you decide to write this book?

Everybody wants to write a book. To write a memoir, you probably have to have a little bit of an ego. But I didn't really think of the memoir as being a me-me-me thing. I certainly don't equate a memoir with an autobiography; those are for celebrities. I'm a songwriter. This is a memoir. Also, I just wanted to present the world through my eyes. This particular book is the world of country music over five decades through my eyes. There are great characters in here. Some are famous. Some are infamous. Some are unknown.

Anybody's life is interesting in the hands of a good writer. And I hope I'm a good writer. There's always so much to write about. I'm just passing along my observations and hoping that people who read this will get a strong sense of what it was like to be in Nashville in these different eras.

Being an observer must be the heart of what makes you a great songwriter.

That's part of it. Part of it was the music aspect of it too, being a musician of sorts. Harlan Howard once said that a lyric was ninety percent of a country song. I totally disagreed with him; I think the melody is an important part. A lot the time people don't even know all the words to a song but they know the melody. I told Harlan, "You've written some of the greatest country melodies: 'Too Many Rivers' goes way beyond the lyric." So it's both.

“Anybody's life is interesting in the hands of a good writer.”

In the first part of the book, you list the neighborhoods and addresses where you lived in Nashville. Did you do this in part so people could see the city as it was, beyond all of the demolition and construction going on all over town?

Absolutely. I'm sort of a history buff. I get excited when someone can make me feel like I'm there, being a part of history. I just finished Dave McCullough's book on the Wright brothers. Everybody who went to school in America over the past century knows something about the Wright brothers, but I not only learned that Wilbur Wright was an absolute genius, I also got a sense of what it was like for these guys to be so very, very famous in their own time and to see what they did turn into something bigger and bigger. Orville Wright lived until 1948. He commented that they'd never had in mind to invent a machine of destruction. That fascinates me and I want to contribute to that too.

There are so many things I don't know much about, but I do know a little bit about a few things. And I want to share those. My book would probably appeal to a graying audience but I hope also to some younger people who want to get some perspective on what it used to be like in this part of the country back then and how things have evolved. And I hope it will appeal to people who want to see the evolution of country music.

This book could have been written by anybody who participated in it and I would gobble it up. Four or five years ago, one of the Delmore Brothers published something he'd written decades ago. It was about them going out on the road in the Forties and the late Thirties. For a guy from north Alabama who did not have a lot of education and was strictly in music, he wrote pretty well. It wasn't scholarly, but he was a great storyteller. I was excited about that book. So it doesn't matter who wrote it, as long as it's written well and tells what it was like behind the scenes.

As I read your book, I began feeling a kind of sadness as well, to realize how many of the places that were important to you and to country music have been long or recently gone.

Absolutely, I would say not necessarily institutions but maybe the attitude and the architecture. I think I describe Music Row as turning into Dubai. I feel a little sad seeing that disappear, but anybody who doesn't like change is in for a disappointment. That's why people who like the old country and wish we could keep hearing George Jones and Merle Haggard, well, it's never really been that way. There's always a new breed that comes in. It'd be pretty stagnant if you just had the same thing over and over and over. People can download or go to an oldies station and hear the old stuff if they want to.

The country music that's out right now, I like some of it. Some of it I don't like. But it's always been that way, in any era of any genre. I remind people that the kids who love the bro country stuff, that's the music of their lives. That's the music they're falling in love to. When they're eighty years old, that's what they'll look back on.

You included very generous lyric quotes in the book, from yours and from some other songs. These excerpts reminded me of how narrative writing was so critical to country music. Love songs were about love -- and pain -- as opposed to partying and drinking. Did you hope this book would remind young writers about what the potential was to write lyrics with more depth that we're hearing today?

I hadn't really thought about it. I guess I do feel that way subconsciously.

“The country music I fell in love with was all about raw emotion.”

The era you describe was a time when country music had a somewhat narrowly defined listenership. Now it's America's music. Is that both a good and a bad thing?

Exactly. I think it's both good and bad. You nailed it.

What has been gained and what has been lost?

I don't know if I can objectively do that. It would be subjective. We're talking about the relevance of the song itself and what it says. But also, as a teenager I loved rock 'n' roll, and those lyrics weren't as good as the bro country lyrics! "Be-bop-a-lula, she's my baby"? We loved it because of the way it sounded, the way it felt, the excitement of it. Sometimes it's hard to define why you like something -- you just like it.

But the country music I fell in love with was all about raw emotion. Men weren't ashamed to cry. And country music has gotten away from that. I love rock 'n' roll and R&B but I always loved country a little bit more -- not always but during my formative years, when I was a teenager. I never loved it as much after the 1950s. In fact, in the Sixties I was liking the Beatles more than I did country music. I loved the Beatles.

You're in great company as a member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame. How do you feel about those who wrote the Great American Songbook: Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter and the rest? Did you learn from their catalog as well?

I'm sure I absorbed some of it. I started to appreciate that when I got much older, the Thirties and Forties. I think George Gershwin influenced me melodically. You absorb what you hear and we hear all these great Irving Berlin songs. I'm sort of a chameleon anyway. When Bacharach and David came along in the Sixties, that even had some influence on me. Randy Newman had a huge influence on me.

What did you learn from writing your first book, Down In Orburndale, that affected how you wrote and researched this book?

The big difference with the first book was that very long-term memory. People who have dementia, everything else is gone but they still remember Mom and Dad and running along the creek with their puppy dog. As I went back to that, it was like the opposite of amnesia. I started to remember things I hadn't even thought about in years. It was almost like I was in a time machine, going back to that era. It was amazing. Some of it was very emotional. Some of it was easy. Some of it was very disturbing. Some of it was pure joy.

With this book, I had about 85 journals to bring from. There were things that happened in the Eighties and Nineties I would not have remembered if I hadn't kept a journal and had access to it. That's the biggest difference. When you read something like that, if your brain is in decent shape, that will trigger certain memories. And that did indeed trigger memories.

It was maybe a little harder to write the second book because there's so much to sort through. The first one, I was writing about the first 23 or 24 years. The second book was about twice that much time.

Did part of your process involve getting in your car and driving back to places where you used to live?

Absolutely. Some things were kind of magic to me. When I first moved here, I didn't know Nashville very well. I knew how to get to my house. But things have changed: Roads have closed. Interstates have come through. I hadn't thought that much about exactly where I lived. I went out to search for it. It wasn't that far from I24 and Harding Place. Harding Place was not extended to the interstate. The interstate went right through where our house was. I went back there and found that street. And all this stuff came back to me. It was like I really had gone back there. There was a lot of magic in it for me because it's long enough ago that it's almost like a childhood memory. It looked rural then. They called it Bakertown. It's now a very organized Hispanic part of Nashville.

Surviving Disappointment

You write occasionally about challenges and disappointments, such as writing a song that you really love, like "The Nerve," and how it kept getting postponed and never happened, or the possibility that Blake Shelton's "Austin" might never get released. What can you say to songwriters today about dealing with disappointments?

"The Nerve" was a disappointment because I feel like it's one of the best songs I ever wrote and it never got beyond being an album cut. "Austin" could have been a disappointment; as it turned out, it was wonderful. It just seemed like everything converged to make it happen, right down to the label folding. But the guy at the label had sent out advance copies to radio stations and program directors, and they were playing it before they were supposed to. So Blake Shelton did not have a label but he had a hit. It was racing up the charts without a label. It's probably happened before then, but I don't know if it ever has.

If Blake could have been transplanted back to the golden era of country music, he would have fit right in.

Oh, yeah! He's a great character. And he knows he's a great character. He's very, very funny. He's excited about the book too. He loves stories. He loves to tell stories and he loves to hear stories.

In addition to writing about historic Nashville, you write a lot about very personal aspects of your life.

How do you write about people you loved and people you've lost? Was that the most difficult part of writing this book?

It was probably the hardest and the easiest part because I have such vivid memories. In doing that, you start revisiting and sorting out feelings. I actually got a different perspective on some of these things than I had before I wrote the book.

Did you get in touch with any of the people you were writing about to make sure you didn't betray any confidences?

There was one girlfriend. I got the feeling that she very much wanted to read it. So I read it to her on the phone to see what her reaction was. She said, "That's just beautiful. I couldn't have said it better myself." I thought, "Oh, wow."

I have a signed document from my second wife, Sparky, granting permission to write anything about us. She's sort of a leading female character in the book. She said, "You can say that I did this. You have my permission." She gave me carte blanche to write whatever I wanted to write.

As I read about her, she sounded like an amazing person.

She was. We're still friends. We talk on the phone every once in a while.

What do you think now as you see traffic get worse and construction accelerate all over town?

Well, I'm an old curmudgeon, but I don't like it! Honestly and truly, I hate it.

“A lot of hit songs were born in a bar or in a restaurant.”

You young songwriters were like writers in Paris during the 1920s and '30s: You were bohemians. Can that spirit ever revive in Nashville?

We're kind of expatriates too. But yeah, I think so. The era I was talking about, the 1970s, was very much that way. A lot of songs these days are written by five or six people. That boggles my mind. I'm sure there's something about it they will always cherish. I'm not saying that the way we did it was the only way to do it. I know co-writers now who could write solo if they want to. It’s big business now, money-wise, there are some lucky guys who will write with artists. Some of those artists are probably good songwriters -- some of them, possibly not. But these people write with four or five hot artists and that's what they do. And they're making millions of dollars doing it. I don't condemn that. I won't condemn anybody for going out and making money as long as it's not at somebody else's expense. If that's the way they do it, fine.

Is Nashville still the place for young songwriters to come?

I think it is. I can appreciate the vibrancy of Nashville as it stands and grows in population. But I hate to see Music Row disappear. Other aspects are disappearing too: the camaraderie of the songwriters. One thing I hope I captured in the book was that back in the 1970s at Tree Publishing Company, which is now Sony Music Publishing, the way they were cheerleading for each other … We would go into [producer/artist] Don Gant's office, sit down on the floor and listen to each other's songs. Everybody knew each other's songs. Every major writer here knew the writers here, including the up-and-coming.

Now, the whole music business is more corporate. It's more of a 9-to-5 thing. In those days, you'd go out and get a drink and say, "Hey, do you want to write a song?" A lot of hit songs were born in a bar or in a restaurant. I've started songs on napkins many times -- and on unpaid bills [laughter].

###