Before being appointed editor of CMA Close Up, the magazine of the Country Music Association, my predecessor Peter Cronin gave me several freelance assignments, which served the dual purpose of introducing the country music community to me and vice versa. At the time I was a stranger in those circles. Truthfully, being a New York transplant, my idea of “country” at the time was a vacant lot in Queens. But I learned the basics quickly and developed some awareness of what the music and Music Row are all about. I remain indebted to those who facilitated the process: publicists (particularly the late Jeff Walker), artists (songwriter Fred Koller, gospel rocker Ashley Cleveland and her husband Kenny Greenberg,) of course Peter Cronin and distinguished scribes including especially the inestimable Chet Flippo.

Not long after I pitched a story to Peter about this intriguing cross-genre project, he departed to launch Cronin Creative and I was invited to helm CMA Close Up. The next eight years were among the most intense of my career. There were exhilarating highs, especially when I gathered a team of students largely from Middle Tennessee to report on the annual CMA Music Festival. For four days and nights, they’d come to our press room in what was then LP Field with their copy. I gave myself a few assignments too, but the true thrill for me was to mentor these gifted writers and photographers. My hours stretched from around seven in the morning to after midnight, after which I would stagger across the John Seigenthaler Pedestrian Bridge and try to make it back to the Hilton before the bars closed at one. Usually I made it – self-reward is a powerful motivator.

Truthfully, though, frustrations were as frequent and sometimes even more profound than the good stuff. All of them involved company rules, stemming largely from a fact made clear to me on Day One: Editing this bimonthly was more of a promotional than journalistic endeavor. Despite this and other restrictions, we did produce a lot of helpful content for our members; I’m thinking of stories we did on tips for tracking effective demos, designing covers for CD and digital packaging, USB wristbands and other new channels for music distribution, cutting tour expenses, fan club mobilization, interview preparation, pitch correction, geo-marketing … even tips for taking pets on the road, creating a unique red carpet look and singing the national anthem.

The problem is, unlike every one of my previous employers, CMA has refused to grant permission to me to include any of the transcripts I’ve retained while on salary. Thus I’m constrained from sharing my better interviews (Porter Waggoner, Merle Haggard, Tim McGraw, Ronnie Milsap, Emmylou Harris, Little Big Town, Lady Antebellum) as well as the ones that didn’t work out so well (Miranda Lambert, Trace Adkins … of course, even if these had been green-lighted, I doubt you’d see them here).

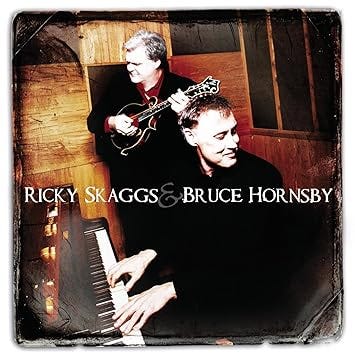

Freelancers, though, were free to repurpose their published work for CMA. So it’s from this corner of my catalog that I offer what I thought was a novel pairing: multifaceted, jazz-oriented pianist, singer and songwriter Bruce Hornsby with bluegrass icon and mandolin wizard Ricky Skaggs. We met on their tour bus, which happened to be parked outside of a concert venue in Franklin, Tennessee, steps away from where I’d just finished my own piano gig at Saffire.

***

What brought you back together for this particular project?

Hornsby: Ricky asked me to be a part of the Bill Monroe tribute record, Big Mon: The Songs of Bill Monroe. He says I was the first guy to say yes and the first to cut a track. And it ended up being the first track on the record.

Skaggs: It set such a high benchmark for the rest of the record. I’m so glad we started with that, as opposed to starting with anything. There’s a bunch of great cuts on that record, but it caused the album to soar.

Hornsby: It was adventurous on that particular song, Darlin’ Corey. I thought he would appreciate a few Bill Evans chords in the mix. We had such a great time cutting that track, and then we had a great run with it. We ended up on Jay Leno and Conan O’Brien. I was part of the bluegrass all-star special they had on PBS. So we talked about it, and Ricky said to me, “Hey, would you consider making a whole record like this?” And I said, “Yeah, of course.” It took us a couple of years to get our schedules together, but we finally did it a couple of Aprils ago.

Skaggs: Bruce moved from one label to another in the meantime, from RCA to Sony. And then BMG merged with Sony, so he’s back where he started.

There’s no escape.

Hornsby: That’s fine, actually, because all my catalogs are in one place. Anyway, that’s how it came together. We met in 1990 at Horseheads, New York. We were part of this ill-fated festival that drew about three hundred people. And then, in ’95 or ’96, Ricky had this show, Live at the Ryman, on TNN, and he asked me to be a part of it. Vince Gill, Béla Fleck, and I were the guests one night with Ricky. That’s when we really felt there was some kindred …

Skaggs: Hot House had just come out at that time. I got a copy of the record, and the front cover blew me away. This was Bruce’s all-star dream band: The Duke …

Hornsby: … Bill Monroe and Charlie Parker …

Skaggs: … all playing together [laughter].

Hornsby: To explain that cover really quick, I felt that cover was illustrated in the music by the cut “White-Wheeled Limousine,” which we did on Live at the Ryman. It had Béla Fleck and Pat Metheny, “together again for the first time.” That was my version of that. I’d done it before with Wayne Shorter.

“I’ve been the ‘new guy’ on this block since 1989.” — Bruce Hornsby

Bruce, you’re the “new guy” in this project, as far as CMA readers are concerned …

Hornsby: Well, I’ve been the “new guy” on this block since 1989, when I was part of Will the Circle Be Unbroken with the Dirt Band. That was my entrée into this world. It made a controversial splash. We won the bluegrass Grammy for our version of “Valley Road,” which we’re playing tonight, and pissed off all the purists. Then I wrote the title cut to Crown of Jewels for Randy Scruggs. Pam Tillis cut “Mandolin Rain.” I’ve always had a strong country influence, from the first record.

Was it your idea to combine your talents under the bluegrass format, or was it more about getting together and just seeing what happened?

Hornsby: I wanted to find a way to make my music fit into the context of Ricky Skaggs and Kentucky Thunder, the greatest bluegrass group going today. So when I was writing new songs, whether it was “The Dreaded Spoon” or “Gulf of Mexico Fishing Boat Blues,” one of the first bluegrass tunes in 5/4, I wanted to fit it into this mode but also twist it a little bit. That’s what I think he likes about what I bring into it.

‘I was saying, ‘I really think this can work.’ Then, of course, ‘Super Freak’ came along, and that was over.” — Ricky Skaggs

Skaggs: We never one time ever mentioned the word “radio.” We wanted so much just to make music. That’s the freedom of having Skaggs Family Records: I don’t have to sit with a committee and ask, “What do you think about this? What’s the single?” So when we got together, I wanted to know what he was thinking. I didn’t want to poison his mind with preconceptions that “I’m only going to do this.” I wanted to hear what he was thinking. So he started sending me some live cuts of things he was doing. I was saying, “I really think this can work.” Then, of course, “Super Freak” came along, and that was over [laughs]. When we play it on the road, I tell the fans, “We’ve killed Rick James again and resurrected him.” And they go crazy. We were at the Birchmere [in Alexandria, Virginia] a couple of weeks ago. Me and the boys did just a little of it. And they just loved it! I think it’s going to be very well received. It is such a musical record. To me, every cut is a masterpiece. Every song is powerful enough to stand by itself.

Hornsby: “Darlin’ Corey” was the template for the stylistic …

Skaggs: It absolutely was. He cut on that same little piano at my studio, a little seven-foot. We actually brought a Steinway in and listened to it, and it just sounded so dark for the banjo and mandolin – the bluegrass stuff. So we ended up using what was there. It was one of those things that worked. The sound of “Darlin’ Corey” was what we wanted, and it really worked well.

Common Ground

Are there any feelings of ambiguity about balancing between a reverence for bluegrass as an established form of music and experimenting with different approaches to it?

Skaggs: Bruce and I have talked about that same thing. I appreciate where he comes from in that he brings along Bill Evans, Bud Powell, Keith Jarrett, and Leon Russell – guys who have influenced him. But he’s such a great player himself that he plays his stuff, and if he wants to all of a sudden pull a Leon lick off the hard disk to go in there, it works because he knows it so well. That’s the same way I am about Monroe. I honor, love, and respect Bill Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs, and the Stanley Brothers. Those three groups, to me, solidified the sound of bluegrass. Bluegrass was sixty years old in 2006; August was the first month that they kept the music [sic]. But Alison [Krauss] and groups like Nickel Creek have proven that this music has to grow. There’s an audience for it out there. The O Brother phenomenon, crazy as it was, it was not a bluegrass record. That music predates bluegrass by twenty years. But people called it bluegrass because they didn’t know what else to call it. They put it in the same category as bluegrass because bluegrass is the most popular name for acoustic music. But I really think that what Bruce has brought to this project is going to cause the music to grow. It’s going to expand its boundaries. Me and the boys go out and play symphony shows; we’re doing the Schermerhorn here in Nashville in February. We have some great charts. Doing those kinds of things causes the music to go out in other directions. His jazz and pop audiences will have a taste … I think they know Bruce well enough to know that he likes bluegrass but he’s never had a chance to experiment with it on a whole record and hear it from start to finish. That’s going to be a great eye-opener for them.

Hornsby: Ricky told me that Bill Monroe always heard a piano in bluegrass.

Skaggs: Yes, he did.

Hornsby: His father-in-law, Buck White …

Skaggs: Buck would sit in at the Bean Blossom {Bluegrass Festival]. They had an old piano onstage because country bands would come up there and play in the old barn that finally burned down. Bill would ask Buck to sit in and play fiddle tunes with him. Monroe said, “I really like that sound a lot. I really want to use piano in my music.” He never recorded with it, but he loved the stuff that me and my band did with “Uncle Penn,” “Wheel Hoss,” and things like: When the piano player would play, he would look over. He really loved that. He would really have loved Bruce Hornsby.

What will each of you take away from this project for your own music?

Hornsby: I’ve developed a consciousness of the old-time fiddle time since I’ve played with these guys. I’ve learned some old fiddle tunes on the piano, which I play with them. That’s been a great education. They’re great technical exercises.

They could almost be like Bach stuff.

Hornsby: That’s right, very much so. That influenced me when I was coming up with the line for “Dreaded Spoon,” which the guys always bitch about to me because it’s real hard [laughs]. That, on a pianistic level, is what I take away with me. But there are so many other things. Ricky turned me on to some real old-time, down-in-the-dirt music by Dock Boggs and Roscoe Holcomb. We ended up cutting two of Roscoe’s songs.

Skaggs: The Bill Evans/Tony Bennett records …

Hornsby: Oh, yeah, I turned him onto those.

Skaggs: … will forever be in my heart. I love it. It just blew me away. It’s one of the best records ever. It’s flawless. I would suggest that record for anybody, any musician. Of course, to get to listen to Bud Powell and Keith Jarrett’s stuff … I’d heard of Keith …

Hornsby: … but it wasn’t the right stuff.

Skaggs: Yeah, I got to hear some things he grew up listening to. Of course, I’ve always been a huge fan of Leon Russell, because he plays such a gospel funk. He’s got that spiritual thing to it that just sets me off. It’s put me in a place with a world-class musician. We have such a musical kinship that my door is always open to doing a volume two. If it sells enough even to just break even, I’m willing to go for volume two, because we’ve already got six songs together for the next record.

When you’re doing a Kentucky Thunder gig, does this experience encourage you to stretch harmonically in ways you might not have previously done?

Skaggs: He brings that out. When he’s playing something, I’ll try to mimic him. Or I’ll do a setup for something; he’ll start on a seven [hums a possible opening for a solo]. Jazz and bluegrass are so kindred. They’re both off the cuff and off your head.

Hornsby: They’re both about virtuosity.

Skaggs: They are.

But what is the role of the piano in this context?

Hornsby: I can create the role. The role is whatever I choose to make it, as long as you’re playing with some sort of taste. What is it? No one knows!

Skaggs: When I was playing country, I always had a piano player in my band. The piano player’s left hand just had to stay with the bass and kick [Skaggs articulates the boom-chuck pattern], just to strengthen that low end, and the right hand was free to play other stuff – but don’t play a third! Play a one and a five, because the third rubs against the guitar and is never really in tune with the guitar. But with Bruce and the bluegrass band, we’re never concerned about him playing right with the bass all the time. He and Mark will work out important lines or runs that are important to play together, but it’s not like a country band setting. The thing is, me and the boys can go out and play some of these songs without Bruce, even though I don’t like doing that. But we’re going to be able to play songs like “Valley Road.”

Hornsby: It’s up-tempo and hitting hard. It’s jacked up!

Skaggs: “The End of the Innocence” is beautiful.

Hornsby: And we’ve completely reinvented “Mandolin Rain.” I improvised it one night in Oregon in 2002, in the middle of a gig. It just came to me, fully formed, at once. I played it for Ricky one day. I said, “You know, this might work.” And it really connected with him.

Skaggs: Oh, yeah. When I heard this, I said, “Man, we’ve got to cut this.”

Are there any songs in your catalog that don’t adapt to this experiment?

Hornsby: We cut “Little Sadie” and “The Road Not Taken.” It was a fine version; it just wasn’t quite as good as the rest of the stuff. And we had too much music; we’ve done at least thirteen cuts, and there are eleven on the record. So the answer is no. And frankly, I wouldn’t think that would happen. I wouldn’t bring “Talk of the Town,” “Long Tall Cool One,” the swing stuff. You know what’s a great bluegrass tune? “Rainbow’s Cadillac” [Hornsby sings the lyric with a bluegrass feel, complete with a vocal break at the end of one line: “People would gather from miles around to see the mighty Rainbow … knock ‘em down.”]

Skaggs: It’s almost like “Uncle Pen”!

Hornsby: That’s right. In my liner notes for Harbor Lights I said that I took this from “Uncle Pen.” Jerry Garcia, when he heard the record, said, “Hey, nice ‘Uncle Pen’ rip, man!” [Laughter.]

###