My dad was, among many other things, a jazz arranger. Starting with the charts he wrote for his fellow soldier Tony Bennett and the U.S. Army Band in wartime Europe, he finessed his skills to the point that he picked up a regular gig writing for Art Van Damme, a moderately celebrated musician who was best known for his choice of instrument: the accordion. To my young ears, he defined its sound: a light tone that skipped over my dad’s breezy grooves, perfect as background music at cocktail parties. Never did his playing or Dad’s charts exploit the power that more aggressive use of the bellows could ignite; as far as I knew from Van Damme, not to mention “the happy Norwegian” Myron Floren’s bubbly renditions of “Lady of Spain” on The Lawrence Welk Show, that was pretty much what the squeezebox did and nothing more.

I can’t remember how or when these prejudices were shattered, but it probably had something to do with zydeco. In the hands of Clifton Chenier, Rockin’ Dopsie and Boozoo Chavis, that tinkly accordion morphed into a beast. It roared and snarled.. Welk’s and Floren’s goal was to tickle the listener’s ears; this wave of Louisiana-bred players engulfed pretty much the whole body in a hurricane of texture, volume and rhythm.

This revelation inspired me to propose dedicating a complete issue of Keyboard Magazine to the accordion back in the Eighties. This was more of an evangelical than academic concept, in that it would open the ears of readers whose preconceptions were similar to the ones I had abandoned. Putting “Weird” Al Yankovic on the cover proved to be controversial; we got more than a few letters expressing bewilderment or even indignation. But it also attracted attention, and I like to think that it led a lot of people into the issue.

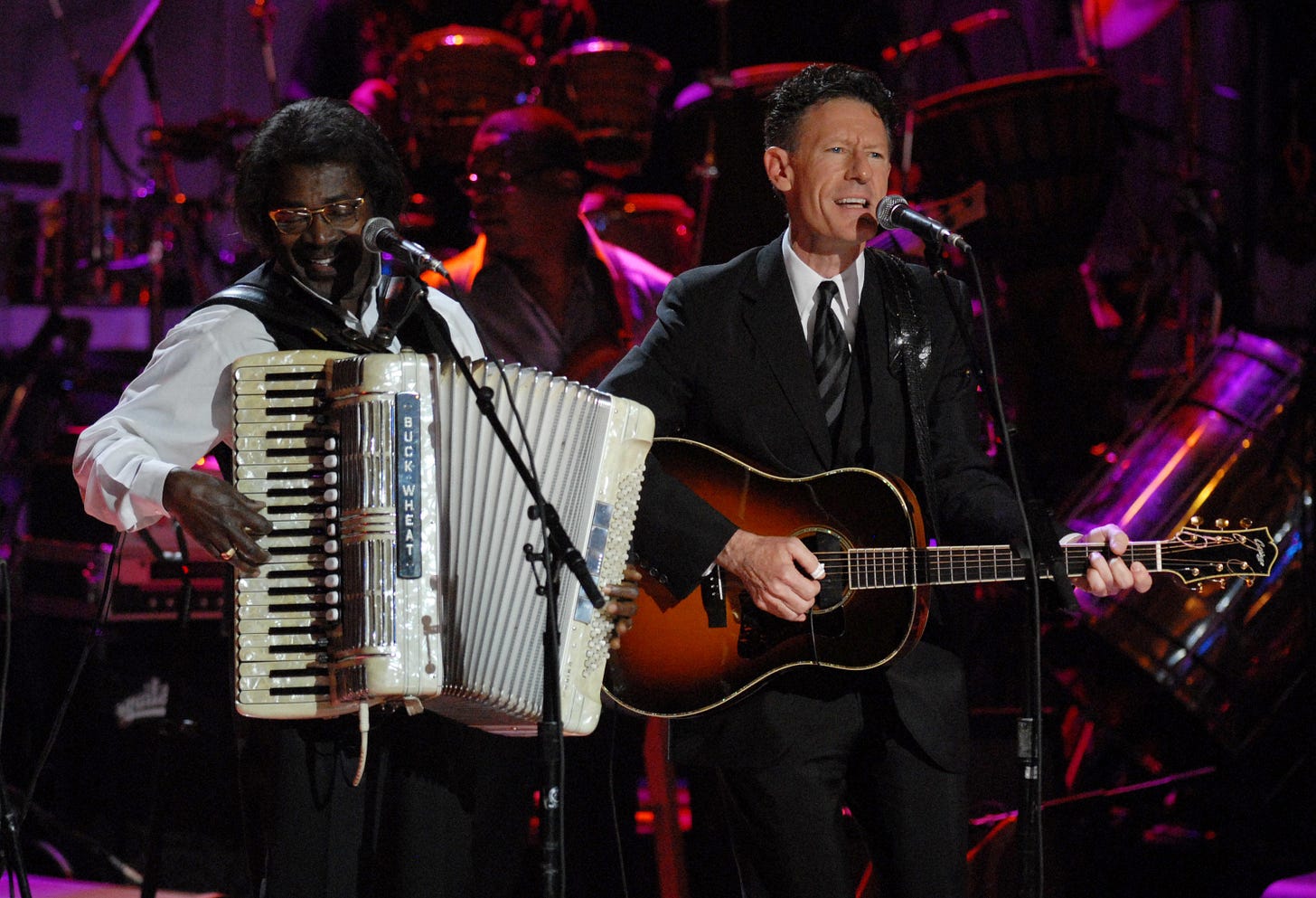

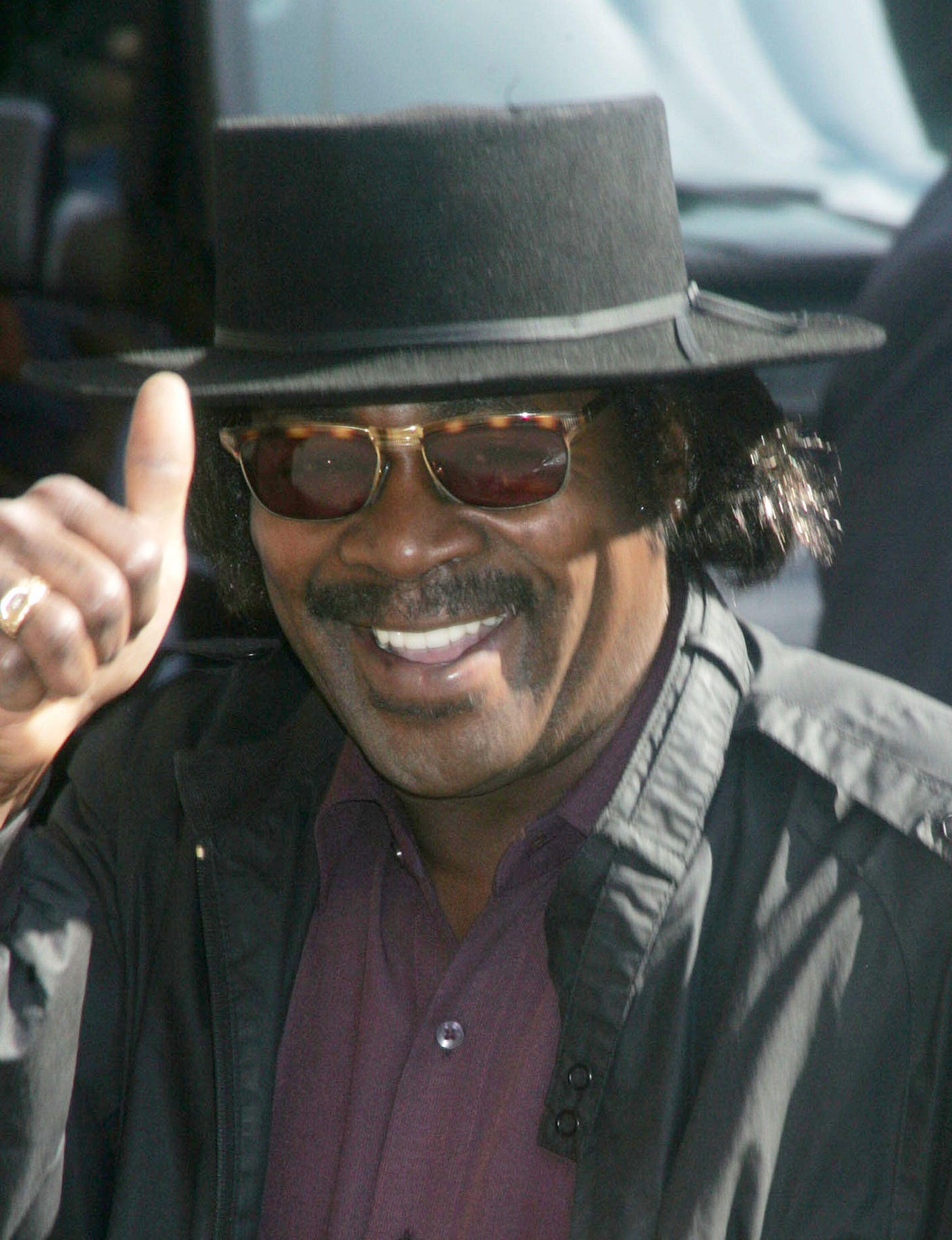

Buckwheat Zydeco was at that time the best known and most widely heard practitioner of this style. It was kind of nervy for Stanley Dural to adopt that stage surname, kind of like Van Damme changing morphing into Art “Martinl” Jazz. But it was also appropriate. If Chenier was the “king of zydeco,” then Dural was its advocate. Being a younger and dynamic performer, with a generational insight into other genres, he could share the stage and studio with the likes of Eric Clapton, Paul Simon and U2. In these respects, Dural stood alone as his music’s ambassador.

I saw Buckwheat play live only once, at Slim’s in San Francisco. My main recollection of that night was the sheer power of his playing, along with his charisma in the spotlight. By the end of the show, having experienced his renditions of “Tee Nah Nah,” “Hot Tamale Baby,” “Walkin’ to New Orleans,” “Ya Ya” and the rest of his electrifying set list, I staggered out the door, my recollections of “Lady of Spain” eviscerated, perhaps until this very moment.

****

What was Lafayette, Louisiana, like when you were growing up there?

Well, Lafayette has always been a city, but as the years went by, man, it just took off. Everything started happening in Lafayette, just like in every city that grows. That’s very different from when I was a kid. Matter of fact, the house where I lived, there were not other homes around it, just land, cotton fields. If I went, I would say, a block behind that house, there’s a road, which was called Lillian Road, and there was nothin’ but fields there.

How many brothers and sisters did you have?

We were twelve kids: seven sisters and five brothers. I had another older brother I did not know, because he died before I was born. I was the fourth kid.

There were only two rooms inside your childhood home. How did you all live in there?

I left that home when I was about eighteen years old, or maybe a little earlier. So did my older brother; I have one brother and two sisters who are older than me, you see. We left that house because we had the younger sisters and brothers, and it was time to go, man, and get on our own.

Your father was a musician. Is that how he earned his living?

Oh, no. He’s a car mechanic. Matter of fact, we all had to learn some mechanic work, the boys and the girls. That’s how come I can fix my tour bus, every once in a while. He was an A-1 mechanic, know what I mean?

And he wanted you to learn to work on cars so you could have a profession to fall back on?

I guess that was in his mind. My daddy had no education, you know. He didn’t go to school. His life was everyday livin’; he taught himself. So many other people who didn’t go to school, that’s what they did. You want to learn and that’s what happens; You teach yourself? He had a lot of wisdom, know what I mean? A very smart man.

Pardon My French

Were you raised speaking French and English?

No. My parents spoke the French language when they didn’t want us to know what they were saying. When you were growing up, with this Creole French, it was like, “You speak English. You don’t speak French.” That’s how I grew up.

Why did they want you to learn only one language?

This is what I came to as a conclusion and so many others thought the same way. You went to school and you spoke French, and the kids laughed at you, like an embarrassment. I hear this a-plenty when I’m in Canada. That’s why you have the situation where some parts of Canada don’t speak French, you know? So that’s what it was. My parents would speak French only to each other, so that we wouldn’t know what they were saying. But I went to work in the cotton fields, matter of fact not too far from where I’m living now, I had kinfolk who couldn’t speak English. So I had to speak French. I learned a whole lot from listening to my mom and dad, but I definitely learned a-plenty from my cousins.

Do you speak both languages equally well now?

Yeah. I did pretty good.

“The first time I picked cotton, I was five years old.”

When did you start working in those fields?

The first time I picked cotton, I was five years old. My brothers and sisters used to leave to go pick cotton, and I always wanted to go with them. Worst mistake I ever made in my life, I tell you [laughs]. I’m serious! My parents decided to let me go, just to see what it’s all about. Oh, what a mess, man.

Were you mixing work in the fields with going to school?

Oh, no. When the school time came, you went to school. That was definite. As got more more children comin’ in, four or maybe five of us had to get off of school and then go to work to help our parents. It’s not like it is today. We had to do what we had to do. That’s just what you did.

Did you make it through high school?

No, I went to work. Let me tell you what I did: I went to school in the morning. When I got off from school, I had another job. The first job that I had was as a delivery boy for a grocery store. I worked at pizza houses. I worked at Ford garages. My brother was an A-grade mechanic too, and he worked on Fords. I did veterinarian work; that’s why you see about twenty dogs in my house right now. I love animals. So I did a lot of work. Man, you had to. If you want to get ahead, you’d better. It makes you understand that things don’t come free, you know what I mean? If you want to do something, you get out there and you bust your booty for it. If it don’t come, at least you know you tried.

And these lessons of life affected your approach to finding success in music.

Yeah, I see what you’re saying.

Too Much Accordion!

Can you remember the first time you heard the accordion? Maybe you were too young to remember now?

Oh, I wasn’t too young. I was playing piano when I was five years old. A lot of things happened when I was five. I was a little kid, bangin’ on the piano. We always had an accordion. We always had music in the house. My oldest brother, Rodney, he was a champion. That’s who I learned from. He also played beautiful piano. I’d just sit and listen to him. Then when he’d get off the piano and go to work, I’d jump on the piano.

Why didn’t the accordion attract you as much as the piano back then?

You gotta remember, I heard it 24/7 from my dad. Pop would come home for lunch and he’d play. He’d come home at night and he’d play. That was enough accordion for me [laughs]. Also, it was the type of music that he played on it, which is what’s happening today. But it was ahead of the time for me. It was good because everybody was having fun. We had family over and we’d cook out. Everybody was dancin’ and partyin’. It looked good to me, but I didn’t know what they were doing all that for because I didn’t care for it, you know? This is because I was playing some Fats Domino and Little Richard on the piano, some jumpin’ music from a different generation.

So your dad was trying to get you to play his kind of music and you were refusing?

Well, you tell me if you think it’s bad. You understand, I’ve been onstage, playing professionally since the age of nine. They’d hold my hand to take me in and out, then they’d open the door [at home] and say, “I brought your son back [laughs].” Now, I was born in 1947, and my daddy never went out to listen to me play until I was with Clifton Chenier in 1976. So you tell me.

Your father didn’t even want to hear you play anything, unless it was zydeco?

That’s what I’m saying! He’s so much in the culture, so much in the roots. It’s that simple, you know? I’ve been playing that many years, since I was nine years old, and my dad doesn’t even go out and hear me. I can understand my mother [not coming out], because she never went to nightclubs.

You would think that musical parents would be excited that their kids are doing music, no matter what style it is.

Well, my dad was glad that I’m a musician. But he wasn’t glad about what I was playing, because he was stubborn. That’s why I’m the only one in my family who’s performing for the public. Man, I’ve got seven sisters, and my family would sing spirituals in church. My mother sang spirituals and I’d play for her on the piano.

I guess it took getting a gig with the king of zydeco, Clifton Chenier, to get your dad to one of your gigs.

Exactly. And I can understand that! I love a lot of that stuff, but there’s a lot of stuff I can’t deal with. I wouldn’t jump up and down behind something I don’t care about. My dad was like that as long as I knew him, until he died.

Childhood Gigs

Describe your first gigs, back in the mid Fifties.

Let’s see. When I was nine years old, we had a little band, Lynn [Lynn August] used to play drums. I had to teach him how to play the keyboard. That was many, many ago. But my education came from Sammy and The Untouchables, to start getting myself into gigs. This guy had a big band: Where Lynn and I played together it was five or six people, and with Samuel it was like ten or twelve people, with horns and everything.

Were you reading charts on those gigs?

No. The only thing I played was the sounds of the notes. I have good ears, but I didn’t know it was a G, I didn’t know if it was a C, I didn’t know if it was a B-flat. I could play ‘em, but I didn’t know what to call ‘em.

Did the musicians in the Untouchables mentor you in any way?

Definitely. They were very helpful. They’d say, “I’ll teach you this.” They didn’t criticize me, you know? It’s amazing: When you see a young kid doing amazing things, you can’t help but love it. That’s how these guys were. I mean, they had me in their band, you know what I’m sayin’? They’d take the time to come out of the car, come up to my door, get me from the house and take me back that same way. They didn’t mind that, you see? That was Sammy and The Untouchables.

Even as a kid you played with some pretty well-known musicians, like Joe Tex.

We were opening for those guys.

But were you making connections that would pay off later for you?

I don’t know how you mean about the connections, but it was advancing my knowledge of the music. I’d just sit and hear some bad cats, man, on organ and stuff. My man was Jimmy Smith. I don’t know if I ever missed any record that Jimmy put out, you know? When he’d come out with something, I’d buy it and try to learn it. He was my idol, you know?

“I didn’t like to do my chores; I preferred getting on the porch and boogie-woogyin’ on the piano.”

What was it like to play in clubs that young? Was it scary? Exciting?

I know it was exciting because I cried when my parents didn’t want me to play in that band. And that’s what I wanted to do. My daddy used to say, “That boy’s got nothin’ but music in his head.” Because I didn’t like to do my chores; I preferred getting on the porch and boogie-woogyin’ on the piano. That’s what I did.

Did your mother at least give you some support as you started laying?

Oh, yeah. You got to understand: The support was there, but you didn’t tell my dad “R&B.” You didn’t tell him “rock & roll.” Now, you’d tell him zydeco, okay? Because he’d tell me, “You need to play the accordion! Like Clifton Chenier!” I can hear him right now. I stopped playing because my dad almost gave me a choice: “Play the accordion or don’t play no music at all.” This is serious, man.

Didn’t he take your keyboard away from you at one point?

Yeah [laughs]! But I’m pretty stubborn myself. So I said, “Okay, I’ll play nothin’! Before I play the accordion, I won’t play anything.”

How old were you at that time?

Twelve or thirteen years old, maybe younger. As I get older, it kind of fades away from me, you know?

Clifton Chenier

Even though you weren’t playing accordion yet, you got to know Clifton Chenier as a family friend.

Yeah. If Clifton didn’t come two or three times a week, he didn’t come at all. He and my daddy were really close friends. He admired Clifton, up to the highest. That’s where my dad was. It was like he knew my future! Look at what I’m doing today, know what I’m saying? He knew something. But I guess you have to pick your own path, man.

Your early memories of Chenier were very positive, then.

Oh, yeah. But, you see, I didn’t really know Chenier. In those days, man, when the older people were having a conversation, you’d get your butt away from there. That was the law, you know? Kids don’t hang around grownups when they’re having a conversation. Or you’d walk around with half of your lip gone. Kids play with kids; you don’t go into no combinations. I see so many amazing things today, man [where kids get in the way of adults]. Had it been me, I would never do that. But that’s how it was. So I’d see him come to the house. They’d sit there and play accordion for the longest time because there were always accordions and the piano in the house.

But even hearing the great Clifton Chenier play in your own house wasn’t enough to win you over to that type of music?

No.

So what did it finally take to get you to strap on an accordion?

All this started in 1976. I’d never played it before in my life. Never played the accordion, never sang, never played zydeco music, until I went to the organ for Clifton Chenier in ‘76.

Lessons in Leadership

At that point, what was your main instrument?

I was just playing the Hammond B-3 organ. I was the leader of my own group [Buckwheat and The Hitchhikers]. I had five horns, man, and five singers and five rhythm [players] onstage at the same time.

How did you get that B-3?

It was a church organ and they were getting ready to renew it. That was at St. Anthony’s Church, I think it was. It was like brand new, man. I paid $1,500 for it and it was a little over fifty years old.

…

What kinds of gigs were you doing with the Hitchhikers?

We did a lot of Texas and around the Mississippi area. We traveled to the northern parts of Louisiana. We never advanced to, like, what Buckwheat Zydeco is. Back there in the Seventies, just jumpin’ out of the Sixties, it was pretty wild, you know? We were opening for people like Bobby Womack, Rufus & Chaka Khan, a lot of amazing things.

What did you learn from leading your own band?

To stay on top of the job. Stay on top of what you’re doing. Stay very positive. It can go two ways, man: the better way or the wrong way. But if you neglect your business, it’ll get away from you.

“Musicians are sort of afraid of me. They say I’m too hard.”

Did you learn from any major mistakes you made at that time?

No, but I’ve seen it happen. You see, where I come from, musicians are sort of afraid of me. They say I’m too hard. I heard it the other day: “I wouldn’t want to work for Buck, man, because you got to be perfect.” Well, you don’t have to be perfect; you just need to be good. They get the wrong impressions. If you put all your effort to what you’re into, you can feel more positive. You can feel like you might have a better goal. How can you feel good about something that you’re not doing anything about? When you’re just sitting on it, wanting it to come to you? First of all, I feel this way: If it’s music that you’re doing, and you love the music that you’re doing, well, then you do it. If you don’t like what you’re doing, leave it alone. Just point-blank, let it be.

You balance control of the band with letting the musicians have fun with what they’re doing.

That’s right, man. You have to. I tell you what: I’m no critic, but it gives me a bad taste in the mouth when I see musicians say things like, “Well, I’m getting paid, so I don’t worry about it.” That trips me out, man. You’re a disgrace to it, you know what I mean? You got people like that.

A Magic Night

As a kid you resisted your dad’s demands that you play only zydeco, his kind of music. So why did you accept a gig with Chenier?

The reason I went to this gig is, I just left my band, Buckwheat and The Hitchhikers. Matter of fact, I was just taking a break, to get my mind back together and see what direction I wanted to take. Then I got this invitation from Clifton Chenier. I had a very close friend, Paul Senegal, the guitarist, better known as Li’l Buck. I once worked as an organist with his group back in the Sixties, when he had Li’l Buck and The Topcats. Now he was the guitar player with Clifton Chenier, so that made me feel a little more relaxed, because I know him and I know what he can do. So I decided to go and perform that one night with him at this club in Lafayette, mainly because my dad always wanted me to play the accordion and he and Clifton were friends. So I said, I’ll go in and do this. Then after the gig, I’ll put the organ back in my van and go back to the house.”

This was supposed to be a one-night gig.

Right. So I wound up going there that night and performing with Clifton Chenier. And this gentleman played, man! He played four hours nonstop.

No breaks?

No. I’d never seen that before. And when he said goodnight to the people, man, I thought he’d performed maybe half an hour or forty-five minutes. That’s how much energy he projected. That was amazing to me. Please believe me, I’d never heard nothin’ like that before. From that one night, I wound up staying with Clifton for more than two years, which surprised me [laughs]!

“This guy, he was playing this washboard with pop bottle openers on all his fingers. It was amazing to me.”

You'd heard the music through your dad. You’d even heard Clifton playing it in your own home. Was there something different about hearing it onstage as a member of the band?

Yeah. Clifton Chenier, he had a saxophone, he had drums, he had a guitar and bass. Then he had his brother, Cleveland Chenier, with the washboard. That was the first time I’d seen a washboard like that, one that was modified so you can put it on your shoulders. See, back home, my dad played the original washboard, with the wooden frame. I remember washing clothes on it. But this guy, he was playing this washboard with pop bottle openers on all his fingers. It was amazing to me, because where I was coming from, they played the washboard with a spoon.

Was it hard to find a place for the organ within the zydeco groove that night?

It was natural, you know? Because he played I-IV-V blues, and that was natural to me. First of all, playing music, I’m by ear. That’s how I learned. So I have a pretty good ear. If I hear something, in less than seconds, I can repeat. So performing with Clifton Chenier, it just fell in the pocket. That’s what amazed me.

Because you didn't know you could play so easily in that style?

That’s right. The thing is, Chenier had good timing. If It was supposed to be on the one [i.e., the first beat of a bar], that’s where he put it. That’s what shocked me, man. I said, “God, this guy’s fantastic!” And this man used to come around [our house] two or three times a week!

Your relationship with Chenier must have changed immediately.

Man, that’s right. See, what you’re supposed to do as a professional is, when you get onstage, you pay attention to your leader or whoever you’re backing up. You give the best of your abilities, 110 percent. That’s where I was. When we’d get onstage, that was it, from beginning to end.

Did he start giving you lessons on accordion?

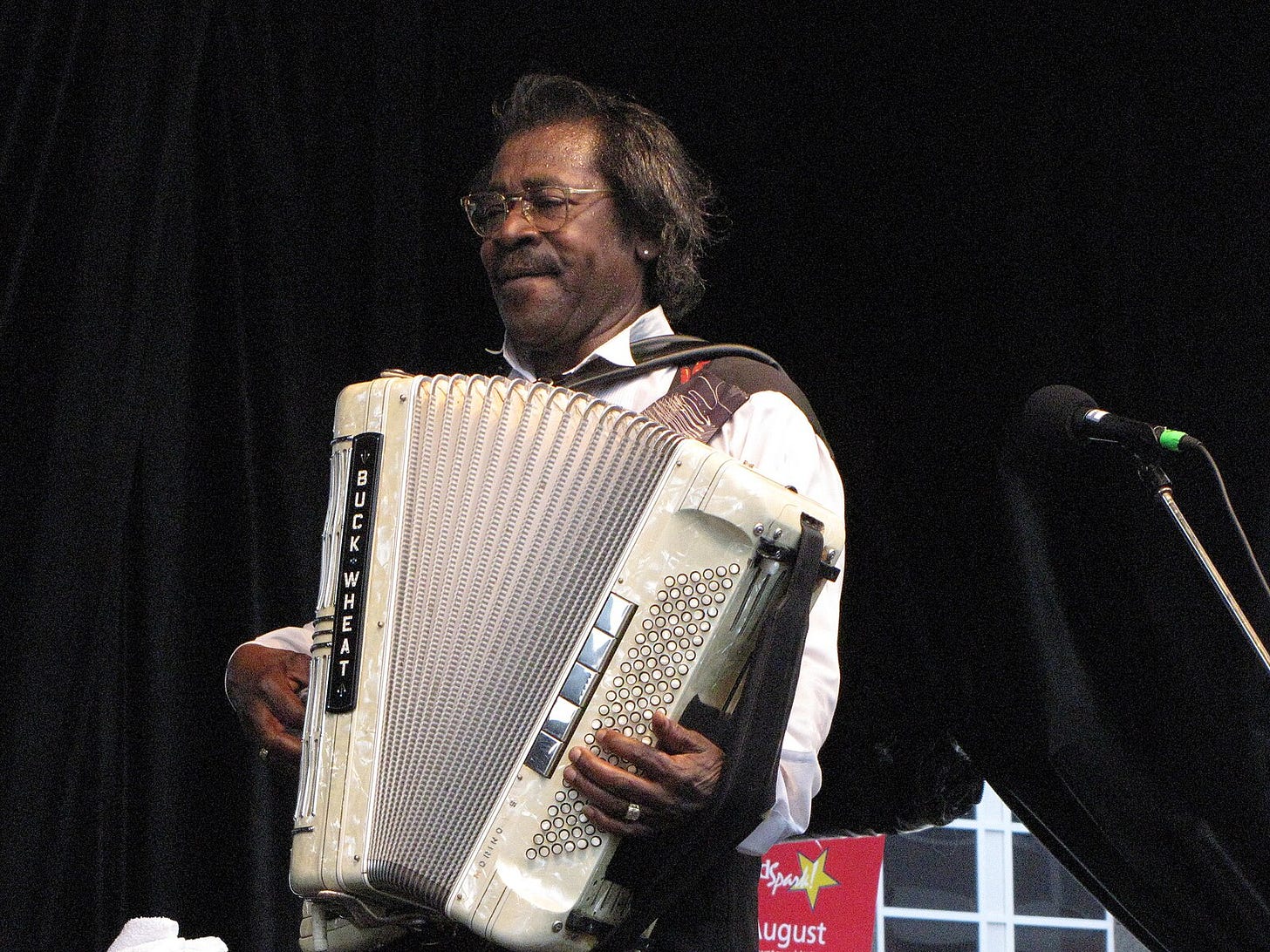

No. When I first picked up on an accordion was when I left his band. That was my decision, because I was so amazed by the instrument. He played a piano-note [i.e., keyboard] accordion, like I do. That’s where I come from, playing the piano. When I got out of Clifton’s band, I’d already made my mind up that it was time to get another group. I’m a leader, you know. I love to do what I do. So I played the accordion. I knew it would be a fight to learn it. The piano part, which is the front end, I knew that, because I’m an organist. But these little buttons on the back [played by the left hand]. those little black dots, that’s what gave me the blues. Many times I’d just sit at home with the accordion. I’d play a while, I’d get angry, I’d leave and I’d come right back to it. I did that for between six to eight months before I even came out with Buckwheat Zydeco, just learning the instrument.

Other than the left-hand buttons, what was the hardest part of learning to play the accordion?

The in-and-out. You have to huff and puff with it, you know what I mean? I had to get that coordination together. The thing is, I can open and close it, but those buttons in the back? See, I’m a two-hand player, so that’s where the problem came in, when you play some of those dots and you can’t even see ‘em. I’d say to myself, “How in the world does this guy do this?” I didn’t know nothin’ about that. Now, my daddy played the one that had buttons on both sides [i.e., a button accordion]. So I said, “No, it’s you or me.” I gave it two and half years. Hey, I had nothin’ but time to do it. That was in ‘79, and by ‘81 I was touring the country: Buckwheat Zydeco and Ils Sont Partis. You ready? We gone [laughs].

“My first gig in Texas was in the parking lot of the motel where I was staying. It cost me seven hundred dollars to play!”

What kind of audiences did you guys draw?

We were going for the older generation. I played a lot of stuff by clifton and a lot of stuff I heard my dad play. That helped me out. But I also had a background of my own, so I mixed what I played growing up together with what the older cats played. That’s what the older generation couldn’t understand. I had to fight, man. I’d get to a venue and I’d pay people to come in: “Just come in for fifteen minutes, man! If you don’t like it, you can leave. I just want you to hear me.

My first gig in Texas was in the parking lot of the motel where I was staying. It cost me seven hundred dollars to play! I’m serious! I sent invitations to a lot of people who had venues. We played a lot of church halls back then, and in order to get in there, I invited them down and we had Creole jambalaya and something like that. If you want to get it done, you’ve got to do it. That’s PR, man.

Both the young and old audiences had their prejudices about whether and how to modernize zydeco. You dealt with that by just bringing them in to hear you.

Exactly. My idea was this: Fifty percent to the older generation and fifty percent to the younger generation. I didn’t think it was fair to perform for just one set of people. I figured, let the hair go with the hide. I was going to give it two and a half years. If nothing happened, I’d be done with it. But it surprised me; within a year or so, it was happening.

Was it hard to find musicians who could play for multi-generational audiences?

Well, my bass player, Lee Allen Zeno, had been with me since he was about thirteen years old. As a matter of fact, he’s my second cousin. His people, when they had cookouts at their house, also had accordions and this type of music, so he heard it growing up himself. So I knew he could play anything; he’s an all-around musician. But you have to work on it. You have to take it to the shop, just like a mechanic with a transmission, and get it in shape. That’s what we did: a lot of rehearsals. I’d say, “This is the direction we need to go. So let’s go for it.”

The main thing is to work together. If you don’t work together, something’s going wrong. You learn what the program is all about, and then you can branch out. You don’t want to say, “Hey, man, I can play this and that …” Yeah, sure, I know you have that talent, but that’s not what we’re doing. You have to put it in perspective, like, I’m playing a rock & roll solo now and then you’re playing jazz. Something will clash somewhere.

Did it take a while to win over skeptical audiences?

I’m gonna tell you what happened. A lot of people came just to be nosey, you know? In other words, “Let me see what he’s talkin’ about. He told me about it, but I got to see this.” that was my idea: “I know you don’t believe I can play this thing, but you come to see me and I’ll show you.” That’s what happened, and then it was word of mouth. They went back and said, “Man, you should hear Buck play that damn accordion!” I’m not a braggart, man. I wear hats every day; my head doesn't get too big. But this is what happened to me.”

And that only makes you better as a player, when you’ve got to work to win over a doubtful crowd.

Exactly! This is the way I say it: If this is what you’re going to do, but 110 percent into it. Give it the best shot you can give it. Even if it’s just a hobby, you want to make it as good as you can.

Audiences today know who you are. They come to hear you not as skeptics but as supporters. Does that make it harder to keep up the kind of energy you drew from to prove yourself?

No. Starting from Buckwheat Zydeco onstage and going out to everybody in the audience, everybody gets involved. That’s how it’s done. When the bell rings and it’s time for dinner, everybody eats. That’s what it is: Everybody who knows what the zydeco means gets involved. As far as being older now, well, I think I still have a little bit of energy left [laughs].

In a way, your life has been about bringing different types of people together through music.

Exactly! We need more of that, instead of all that fussin’ and fightin’ stuff. That’s the way I feel when I get out onstage and see thousands of people out there, all together. When I play a song and thousands of people are dancing, that’s unity.

…

Under the Knife

You’ve had some voice problems recently. What happened?

Too many cigarettes, man. I’d been smoking since I was a teenager. It’s built up what’s called a dysplasia on my vocal cords. It’s like plaque, and it grows until your vocal cords stiffen and don’t work anymore. That was my problem. I thought it was because of the different climates, like when I’d leave from here and go to Canada or some different places. But I got an appointment with my doctor here in Lafayette. Dr. Robert Tarpy. He found this on me and he sent me to Dr. Robert Ossoff at Vanderbilt in Nashville. Sure enough, they had to go in and scrape my vocal cords.

Did you feel better as soon as you woke up?

Well, it takes a while. The hardest part for me was that you can’t talk for weeks. Matter of fact, I couldn’t talk for a month. For somebody who’s gabbin’ all the time, that’s pretty hard [laughs].

I assume you’re off the cigarettes now?

Oh, yeah, man. You know, it’s so hard to stop smoking. … The thing is the nicotine, man. I wish I’d never put a cigarette in my mouth. Never. That’s my advice to any person. Not just singers: It could be teachers or anybody who uses his voice all the time. I never thought I’d be the one saying, “Don’t smoke cigarettes.” I never did mess with drugs, Some drugs, I don’t even know what the hell you’re talking about. But cigarettes really messed me up. Thank God that I caught this in time. Do you smoke?

Never did.

Bless you, man.

[Postscript: Buckwheat Zydeco succumbed to lung cancer on September 24, 2016, in Lafayette, Louisiana.]

####

I love his version of "When The Levee Breaks".

I miss him to this day. I saw him live two or three times, I can’t remember clearly because those were party days! What a show. He took one break in the set that I remember the most, and that was to change his shirt which was soaked with sweat. Never anybody like him I hope there will be again.