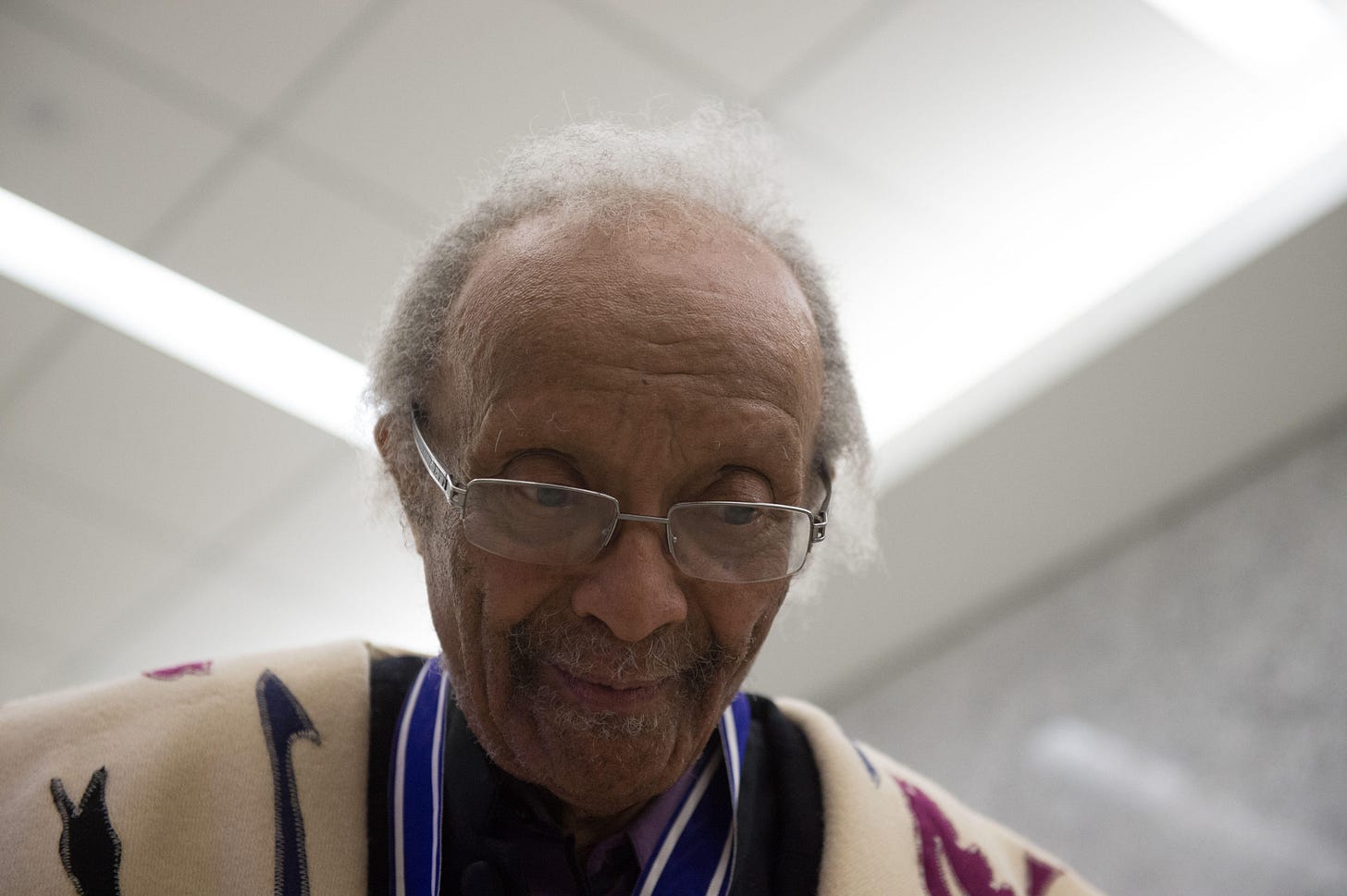

Cecil Taylor

Keyboard Magazine, January 1985

I arrived In New York for my interview with Cecil Taylor just a day or so after the transcendent avant-garde pianist had moved into his new home near an airy, sun-splashed house near the Brooklyn Academy Of Music. As I recall, I was staying at a hotel in Manhattan, so his publicist picked me up and took me on a short tour of places that had meaning to her client. We passed venues where he had recorded some of his monumental live albums. I think we also drove by a restaurant where, even as those who revered him around the world listened to and analyzed his work, he worked regularly as a dishwasher to help pay the rent.

I do remember making one stop, at an apartment where he had lived either at some time in the past or just before relocating to the borough. It was dark and cramped but, the publicist explained, it had some history; years before Taylor moved in, this had been Charlie Parker’s flat.

From there we headed to Brooklyn. I skimmed the notes I had brought with me, a combination of biographical background, quotes from and about Taylor from other sources and thoughts that had popped into my head over the previous few days that I had spent cramming on his material. There was a lot to digest but I had been guaranteed that I would have all the time I needed to touch every base: his roots in both classical music and jazz, his unprecedented explorations of free improvisation and shattered tonality, his revolutionary technique, marathon solo concerts, theatrical productions and original poetry, both of which he occasionally wove into his musical performances.

It was early afternoon when we arrived at Taylor’s residence. There, he greeted me warmly, with an almost old-world grace: a smile, a small bow, a sweeping gesture inviting us in. The place was nearly bare, with only spare furnishings and a few African artworks arranged on the wall or on stands. The floors were wood, immaculately polished. Most of his possessions, he explained, had yet to be delivered. I noted how much room he had here. He touched my forearm.

“It is amazing!” he exclaimed. “For most of my life I lived in Manhattan, in these tiny flats. I barely saw daylight.”

“Why did it take you this long to leave?”

He replied, “When one lives in Manhattan, one doesn’t dream of living anywhere else! When someone suggested to me that I think about moving, it was like a revelation. I wondered, ‘Why hadn’t I thought of that?”

His guests laughed along with him. For a few minutes I relaxed as they talked among themselves. After a while, some other friends of his arrived at the front door, bearing housewarming gifts. Taylor welcomed them as well. Tea was served. Time passed. I began to get restless. It was almost as if the host, expansive and entertaining, had forgotten why I was there. I believe the sun was starting to set when I excused myself and asked the publicist if she could step with me into another room.

“What is going on? We were scheduled to speak several hours ago. I’m thinking maybe I should just head back to the hotel.”

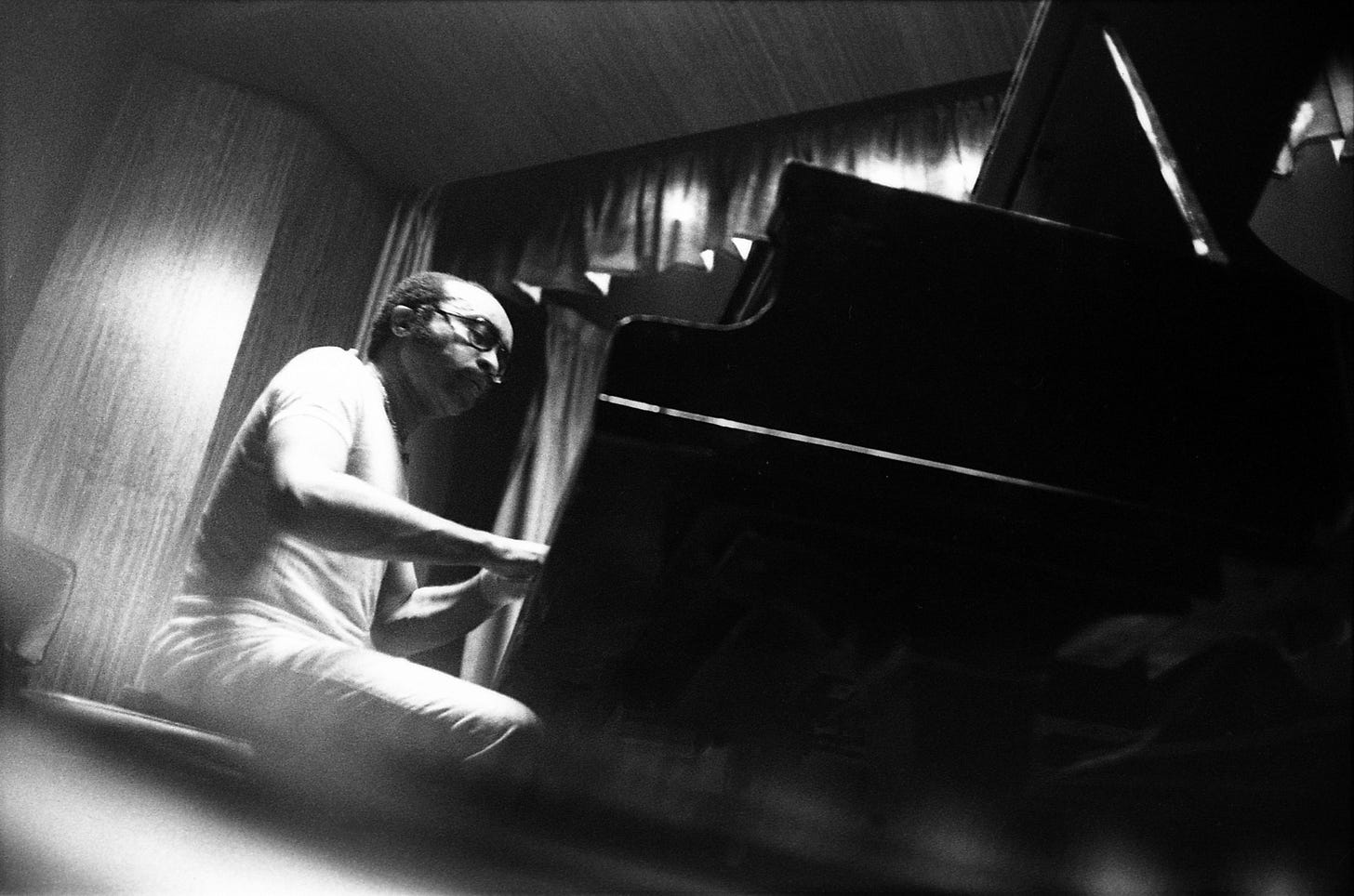

Alarmed, she asked me to step downstairs into the studio and wait. I grabbed a chair a few feet from the Steinway concert grand piano. Just a minute or two later Taylor swept in, graciously apologizing, and then settled onto the nearby couch, curled into a comfortable position and we began.

(By the way, this transcript illustrates a methodology I often try to follow in doing interviews: When the artist says something provocative or enigmatic, using one particular word to encapsulate the entire idea, I like to take that word and work it into my next question. You’ll see this several times, in my repetition of Taylor’s emphasis on “thrust,” “temples” and other carefully selected words or phrases. … Cecil Taylor passed at his Brooklyn home on April 5, 2018. He was 89.)

****

You’ve said that you play most of your gigs at home these days. I suppose that makes the process of selecting a house that much more crucial to you. What did you find in this house that let you choose it as the center for you and your music?

Well, it doesn’t really matter where you’re living. After finally understanding the challenge that my aesthetic point of view means to musicians, and also to business people, it became incumbent upon me, not having gigs, to fight for my own development. The place you fight best is in your own home, wherever that is. So you practice at home.

What sort of practice do you do?

Well, it really begins with the breath of one note, with hearing and experiencing that, and the separation of that note from all the notes that you play.

You view each note in your practice as a separate entity?

I think it’s all about finally making clear to oneself the kind of form that you want, and using that to make the one note sing.

Do you practice the connection of notes, the phrasing, after addressing the notes in their singularity?

I think it begins with the attempt to make the note one in itself … a universe.

Well, in actual performances are the actual notes you play as important as the overall contour or texture?

I don’t make a separation. You begin with the first note and the aesthetic processes that shape the touch and the hearing and the breath of the first note determine the accumulation of the pulsations, the contour of the notes.

“One hears oneself sing at the same time that one strikes the note.”

In A. B. Spellman’s book Black Music, Black Lives, Buell Neiglinger said that singing was an important part of your process: “He’ll sing a phrase, and then he’ll harmonize it at the piano, and then he’ll sing it again, always striving to get the piano to sing.” Is your voice in fact an important part of your practice at the piano?

What happens is that one hears oneself sing at the same time that one strikes the note. There is no separation.

…

How should people listen to your music: analytically or in terms of surrendering to the effect of what you do without trying to figure it out in musical or historical terms?

I really have no demand that I can put on the listener. At this point, however, I think those people who do come to my performances have an idea of what they’re going to be in for, in terms of the totality of the experience that they may receive. They may not comprehend, in which case they have the option of leaving, and you don’t worry about that.

You’re not offended if somebody walks out?

Oh, no! Actually, I’m amused [laughs].

…

When you started playing, did you begin with improvisation or with pieces written by someone else?

Well, Mother gave me the first piano lesson that I had to learn. But she always allowed Sunday for me to do whatever I wanted to do.

How different were those Sundays for you?

It was about what I wanted to hear, getting in touch with a particular spirit of the universe that informed my particular thrust. And I was allowed to do that.

Were you aware even as a child that you had a unique musical thrust?

In retrospect, one becomes aware of it. But fortunately, the home environment allowed me that one day to do that. The catechism had to be dealt with during the other six days of the week.

“Practice … is the preparation to celebrate one’s entrance into the temple of invention.”

Were you a frustration to your teachers?

Yeah, I was, of course. I never practiced. I always had a problem with any authority, outside of my mother’s. You know, life depended upon genuflection. It really does depend on that. I’m very fortunate that certain spirits have chosen this body as a vessel to pass through, and that allows me to do what I do. I realize that maybe it’s easier to say that at times than to live it, but it has nothing to do with my ego. It’s something that makes stones stones, trees trees, plants plants and my cat a cat. The life force inhabits all of this, and music to me at this point is really the celebration of the life force. And practice, which I still believe in, is the preparation to celebrate one’s entrance into the temple of invention.

What impact has the business of music had on that element of celebration in music?

The reality is that there’s a commercial margin which we must find and choices we must make to perhaps go beyond that. It’s a question of whether we can develop suitable options in terms of areas in which we might express ourselves.

When you spoke about playing most of your gigs in your living room, were you saying that, given those realities, it might be better for you to not play at all in public than to play in a way that didn’t feel right for you?

Oh, that was a choice I dealt with years ago. However, what one chooses to deal with as years go by becomes easier when one understands the limits placed on one. And then one deals within those limits to create temples, pyramids.

How did you deal with that choice?

Not very well. But I’ve been fortunate in that I’m still alive and that I’ve had opportunities to grow wiser. That’s what I mean when I say I’m having more fun now than ever. All things are possible, but one must be centered. And one must believe totally in the spiritual essence of the music and then make the necessary adaptations because a society is always changing. The machine that is the force determining whether the music we play is heard, it too is alive. It too is doing investigations. Finally, it becomes easier because one no longer confuses absolutes or morality. One begins to understand morality. One begins to understand reality. And then one makes a choice. So I can enjoy Michael Jackson — but I enjoyed Michael Jackson eight, nine years ago.

Or go see A Chorus Line, as you did the other night.

And learn!

Yet there must have been a moment when you began to realize that you were speaking with a different musical voice.

Well, the thing about that is, that didn’t happen until I had made my first record. Upon hearing it, it took me at least three years to get over the shock, because I had always considered myself as paying homage to the great geniuses who had preceded me. What that first record made very clear to me was that what I had done with Ellington, Waller and Monk was very personal.

Because you had never heard your music from the listener’s standpoint rather than from the midst of its creation.

Yes! The personal process is always different from what you objectify when you hear, because when you hear from outside it’s always as though someone else is doing it.

You really weren’t aware of your sound relative to what else was happening in jazz. You were just making music.

Yes. Maybe it’s hateful to use the term, but when one hears, one must objectify. Then there is a whole process of thought patterns that comes out of that, which are startling and disturbing.

What exactly is the difference between what you heard and what you thought you sounded like?

I think what happens is that you imagine that you are sounding much closer to the people that you would most love to emulate. From outside you hear all the other ingredients that make you sound the way you really sound. You can hear the people that you emulate, but you also hear other forces that make you … an individual voice.

Did that include non-Western elements of music that you hadn’t consciously assimilated?

I think I heard everything I’d ever imagined I had heard.

How were you able to absorb these elements into your work on the piano, with its Western diatonic scale?

The limitations of the instruments always strike you. The surprise is that, given the limitations, you begin to hear these other things that you thought you had digested invisibly before.

In the beginning of your career, you played with a lot of traditional swing-type musicians. Did you ever feel a dissonance between your obligations in backing them and your own developing style?

No, I never felt that. I felt that I was privileged to play with them because it seemed to me that they recognized something in me and they informed me in a way that made me attempt to do things that I would later develop on my own. They gave me the information I needed. It was always a positive experience with Hot Lips Page and Johnny Hodges.

You were playing standards in those days. Is it still important for young musicians to develop themselves through playing those tunes?

No, because times have changed now. You play your own repertoire now, and then you get validation of your own repertoire. If you are really into your own repertoire, the nature of that will make you go back and perhaps investigate that which preceded you.

How do musicians discover their own repertoire?

Well, the problem that I’ve been thinking about is that so many pianists repeat the mistakes of teachers who have themselves been molded by similar teachers, so that the attitude and the shaping of the style is with a language that is commonly accepted as being the piano language, rather than seeing the piano as just one instrument that makes a sound, on which you attempt to imitate the sound of nature.

Are you striving for sounds in your playing that are beyond the limits of the piano?

Well, of course I understand that you could always hear the great people who inspired me on the piano when they played. Then, if you hear the Kabuki or the Bunraku [traditional schools of Japanese music], if you hear the Abuti or the Azuma, you understand that these are part of the voice that they didn’t understand in the West. You understand the connection of Louis Armstrong to it, and the universality of the music they labeled jazz, which I might call something else, was in touch with it. So now, for instance, we do use our voice in performance.

The idea of limits can be better described as a process of better understanding the nature of what one’s life work is about. One works always to move beyond the limits that one is very much aware of one year. You work at it and then a year later you’ve moved maybe an inch further. You remember John Coltrane’s piece, called “The Inch Worm”? By inching, you make music your life’s work.

The process is as important as the product.

The process is the magic of it [giggles delightedly]. Yes!

“I’ve always been trying to work to be able to make that one note sing!”

Do you plan to explore what some people perceive as a more consonant style of playing?

But I’ve always loved Billie Holiday! And I’ve always been trying to work to be able to make that one note sing!

Your piano lines sing in a more aggressive way than most listeners are used to, though. Where an artist on the ECM label might play a melody or a solo line in single notes, you often play yours in minor seconds, which some would consider to be more dissonant.

No comment on ECM [laughs]. No, that was a joke. The point is that I have recorded very clear pieces that would be called ballads, but because of my history they’re simply not heard as that.

Still, your music often puts me in a reflected state of mine that isn’t that different from what I sometimes get from ECM, which seems surprising because of the constant activity in your playing. Why have you apparently rejected static chords and long sustained sounds in favor of your usual busy lines and flurries of notes?

I think that one’s conception of what one does becomes enriched the more one does it. One may think at a certain time in one’s life that vertical structure is stationary within the boundaries of the weight applied by the piling of tones upon one another. But as one grows one sees those innards breaking apart and standing independently of the verticals.

Earlier in your career you did play blues progressions with vertical chord structures. Why doesn’t that framework work for you anymore?

What happens is that one adds to one’s experience. All work is built upon the continuing aesthetic experience. One adds to the body of the work; the forms change in themselves by themselves.

“The piano to me is in itself an orchestra.”

Do trained pianists and teachers have trouble comprehending what you do because your technique is so far outside the boundaries of their tradition?

Well, the other thing is that most piano teachers would appear to lack courage, because I don’t hear from them.

Have you taught many students yourself?

Very few. I rather shy away from teaching pianists because the piano to me is in itself an orchestra.

You’ve talked in the past about Western notation representing a separation of the musical process and the intellectual perception of that process. Today you also spoke about the intellectual phenomenon of perceiving unanticipated elements while listening to your own records. Is there a similarity between recording and notating music for you?

See, it is an intellectual process to understand that there was that separation on my records. But you’re doing what it is to record, you do the best you can, although you are forced into an artificial environment in the recording studio. The intellectual doesn’t have anything to do with it; the weight of what you respond to is one of the prime forces. The emotional fact of all that makes human beings human beings.

My contention is that the emotional thoughts are the basic determinant and the intellectual selective thought process determines which aspects you have chosen from the world view. The blood of my family does not encompass only one thing; it encompasses maybe three or four different cultural manifestations.

So from the very beginning you knew that there were many cultural paths open to you?

As an only child, brought up in a special, i.e. precious way, I was not aware of anything except what I was allowed to do. At that point one is dealing with the opportunity that the immediate environment of home allows one to do. As one begins to venture forth, it’s at that point that you discover how to let the self-protective armament, which could be translated as ego, protect yourself.

If that ego compels some musicians to struggle to master conventional modes of musical expression in order to win recognition through competition with their peers, then your music seems to be extremely free of ego.

Well, since I was involved in track, basketball, softball and baseball, I’ve always been competitive. But when one gets older, one understands that for all the grace of the gymnasts, or of Willie Mays and Joe DiMaggio, athletes usually leave their careers behind them at 35. The truly great poets are maybe reaching their first period of greatness at 35. That’s how Lena Horne, approaching 70, is for me far greater now than ever. Gil Evans, to me, has continued to develop.

What bridges those two worlds — the athletic world of youth and the poetic world that emerges in later life?

I appreciate the athletic world, but the world of poetry is another level of human development. Young gymnasts can inspire, but great poets can really excite.

In our last interview, you mentioned a book you were working on, titled Mysteries. How is that going?

That’s probably turning out to be a life work. A lot that I have written is an attempt to analyze the cultural process that gives birth to the spiritual art. Other statements I would align side by side with musical instruments, the sources of musical inspiration, but they may be directed to questions of human experiences as such.

You’ve noted that Mysteries will focus specifically on the black music in America. What is the greatest misconception that white America still has about black music?

Ignorance of the magic of rhythm.

Is this something that can be eventually communicated? Or is there a permanent misunderstanding?

[Smiles.] One likes to be … optimistic.

Bravo, RD.....a great read and interaction with Cecil Taylor, who's music still challenges me in a way very different from all other. This will have me digging through the LPs to test and challenge my listening skills and the ability to let go and let the music take control.

What a FANTASTIC interview. Thanks for sharing it.