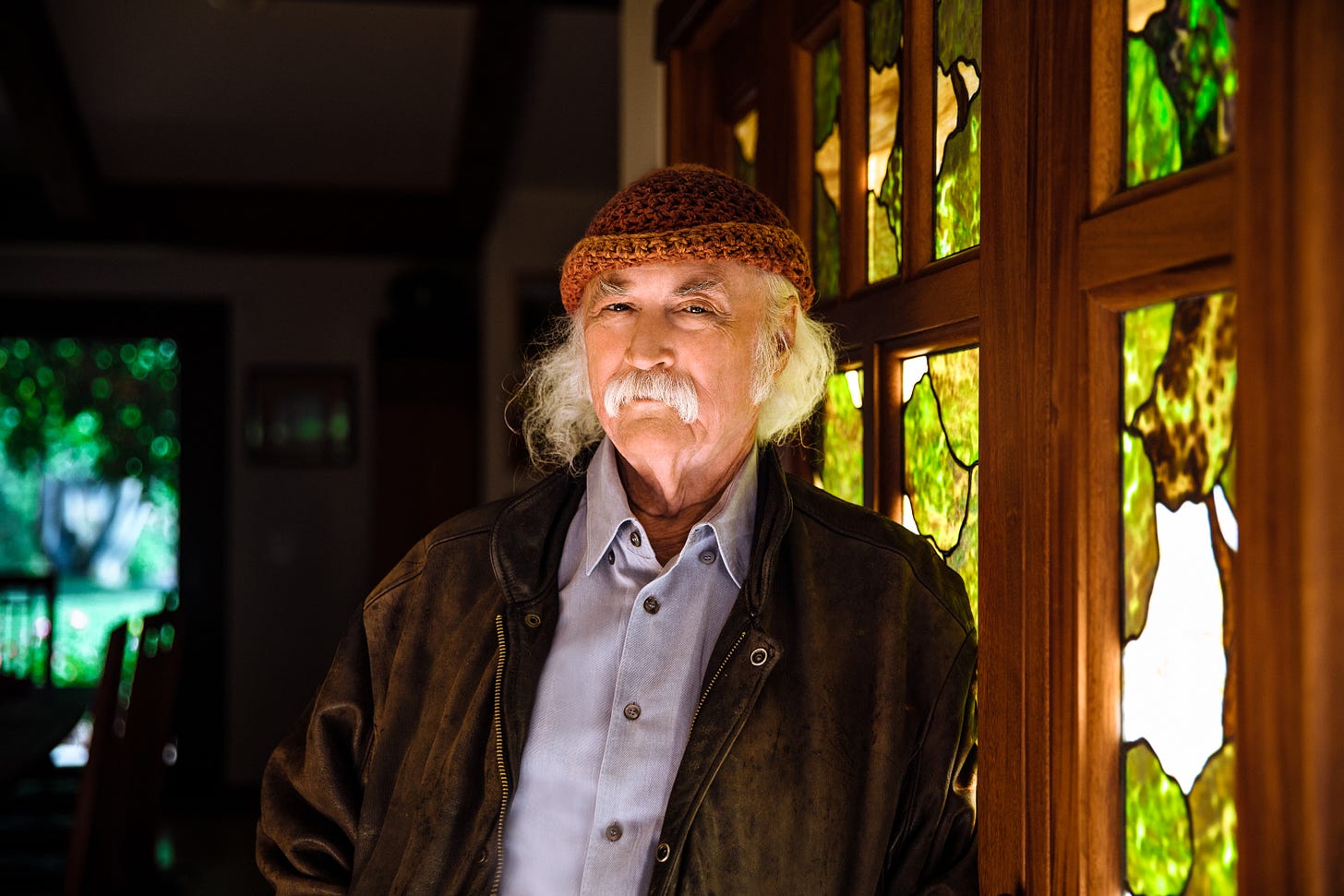

I’m still kind of amazed that I got to spend a lot of phone time with David Crosby for USA Today. Twice, in fact: Once to tie in with his 2017 album Sky Trails, the second time to reflect on Here If You Listen, from 2018. In my opinion, our first conversation was the more rewarding, I think because that project had a unique importance to him, because it marked his first major collaboration with James Raymond, the son he had given up for adoption shortly after the child’s birth in 1962.

Raymond had already distinguished himself as a musician prior to learning that his father was one of the most important figures in American music history. Prior to his reunion with Crosby in 1995, he had served as musical director for the Roundhouse series on Nickelodeon and toured as a keyboardist for Chaka Khan, Take 6 and other artists. Within a couple of years they were working together onstage and in the studio, all of which served as prelude to Sky Trails, on which their respective essences as musicians achieved full synchronicity.

As I researched before our interview, I felt drawn into this story more than I had expected to be. In particular, it touched that part of my own life that involved tracking down my wife’s birth mother. While the results of that particular effort weren’t as harmonious as I had hoped, they motivated me to explore with Crosby this more personal angle. Happily, he was more than open to talk about it. In fact, he encouraged me to share my parallel experience with him how my parallel. Those parts I omitted from the transcript and of course from the story itself. But I want to say here that it continued for a while after we had wrapped up the story, through an exchange of personal emails that ended with his assurance that I had proven myself to be “a good man.”

To hear that from anyone warms the soul. From Crosby, it was a glow that lingered for quite some time, all the way up to that second interview. To my surprise and, honestly, my disappointment, he didn’t seem to recollect any of what we had discussed before. As a result, I think that interview was more perfunctory, less illuminated by that sense of connection I felt we had shared.

In retrospect, of course I do not blame Crosby for any of this. In his many decades of controversy, recreational substances, sometimes chaotic personal adventures and above all countless and immortal accomplishments, one chat with one phone voice from years before isn’t something I’d expect him or anyone else to have kept fresh on the burner. But I can testify that when one is really connected to him, there is no better listener, raconteur or conversational enthusiast. At least I’ve never met one.

###

You’ve worked with your son since your first solo album but you connected with him in the Nineties.

I connected with him when I had my transplant twenty years ago. I knew that he existed but you can’t find an adopted kid from the parent down. It’s only from the kid up. When he tracked me down and found out I was his dad, he’d already been a musician for twenty years. We had a really lucky thing happen, man. Instead of either one of us bringing some bad baggage to the meeting, he gave me a clean slate. He gave me a chance to earn my way into his life. The writing we’ve done together is some of the best I’ve ever done in my life.

How did you get to know each other musically and find ways to collaborate?

I can tell you exactly how it started. I said, “Do you like our music?” And he said, “Eh, it’s OK [laughs].” But he listened to Billy Joel and Elton and two or three other keyboard players. That’s who he really liked. The truth is, he did love our music. He just didn’t want to butter my toast. He’s a very sophisticated guy, man. He’s listened to a ton of jazz. He writes very sophisticated stuff.

There’s some jazz influence on Sky Trails. So you found areas where your differences came together in complementary ways.

I haven’t found an area where we have any real differences. We’re certainly not identical but I hear his thing so completely. It sounds so right to me. And he certainly knows where I want to go.

About two seconds into the first track of your new album, I thought, “Wait a minute. I’m supposed to be getting a David Crosby advance. Why did they send me Steely Dan?”

[Laughter.] Yay!

What does this album represent to you in the context of all your solo albums?

OK, this will take a little framework. You have to understand a number of things about this record. This is the third in a triad of records: Croz, Lighthouse and now Sky Trails. My son James Raymond produced Croz and Sky Trails. My friend [Michael Liddie?] produced Lighthouse. They are quite different in that James produces full-band stuff generally when he and I work together. We sometimes use horn stacks. We tend to make that kind of music. Not all of it is: There’s a Joni Mitchell tune on there that’s pretty much piano, pedal steel and my voice.

This is a very unusual thing in my life, man. I’ve never been that prolific. I write two or three songs a year. I think some of them are good but I haven’t written a whole lot of them. But now I’ve written and recorded of what I think are my best records in three years — bang, bang, bang, just like that. How did that happen? How are they different? Well, Lighthouse is a very acoustic record. It was done so on purpose. Sky Trails is a very electric record. It was done so on purpose.

But the body of work of these three records is a little puzzling, man. I’m supposed to be fading out now! I’m at the end of my life! I should be someone you see on crutches who says, “Hi! remember me?” I don’t feel like that at all! I feel great! I love to work. Working on the road is harder but I love recording.

Now, to put a sad note in, there’s not much point to it other than it’s good art and it will last longer than I will. Nobody’s buying records anymore because the streamers killed the record business. They’re stealing my music and they make billions of dollars selling it without paying me.

You might get a check for thirteen cents for thousands of plays.

Exactly. Roger McGuinn told me that he’s had some huge number of plays for “Eight Miles High” and he got, like, twelve dollars. It’s nuts! I can’t say anything except I hate them.

But to go back to the songs, this record is different from the previous one because of its electric nature. But these three records represent a resurgence for me, a kind of rebirth. When bands get together, they love each other at first. They love each other’s music. They’re really excited with it. Forty years later, most of them devolve to the point where they just turn on their smoke machine and play their hits. That’s what happened to Crosby, Stills and Nash. We didn’t like each other. We were not having fun. And I got out. I quit. I’ll take the blame. That’s not to say I don’t treasure that music. We did good work. I’m proud of the work that happened with the Byrds. And I’m proud of the work that happened with Crosby, Still, Nash and Young, which is a completely different band.

But I need to keep moving forward. That’s what this record really is. It’s me trying really hard to keep forward motion going.

Your three recent albums differ in orchestration. But what about the writing? On Sky Trails did you begin writing new songs with the idea they would be played by a bigger band? If so, did that impact the kind of songs you wrote?

No. I write all the time. I write every day. When we were making Lighthouse I was writing these songs. The minute we finished recording Lighthouse I came back to the studio the next day and started work on this record [laughs].

The truth is, man, I don’t see them as records until I assemble them. I see it as me serving the songs. First I try to create songs. Then I try to serve them. I try to make them have a life. But I don’t plan records out ahead of time and orchestrate them to fit my concept. I accept what comes to me and try to build something coherent out of it.

So if you had written some of these songs earlier, you might have done them in an acoustic, more intimate setting.

That’s entirely possible. We could easily have done Joni’s song, “Amelia,” on Lighthouse. It would have been very good there. But it wound up here.

Are any of these older songs that you pulled out from your archive?

The only thing that’s not new is the Joni song. I fell in love with that song when she wrote it. I had dinner with her the night before last and I got to tell her again how much I love that song. It’s such a beautiful piece of work. The truth is I was really intimated by it. For a long time I didn’t think I was good enough to sing it. But I loved it so much that I couldn’t resist it.

To my ears, a good portion of this album is an homage to Joni. The piano chords at the top of “Before Tomorrow Falls In Love,” the raised fourth in the melody and the soprano sax improvising on “Here It’s Almost Sunset” … these really bring Joni to mind.

Joni has influenced everything I’ve done since I met her. There was a definite influence all the way back to “If I Could Only Remember My Name” and in everything else I’ve ever done. She and Bob Dylan are the biggest influences in my life. She’s a consummate musician and the best songwriter of our time. I don’t think there’s really any question of it. So, yeah, she influenced this record … but she’s influenced everything I’ve done.

Did you do alternative tunings on your guitar throughout Sky Trails?

Oh, yeah. In fact I don’t think anything I did on this record is in regular tuning [laughs]. I work mostly in other tunings, man, because it gives me interesting inversions of the chords. It takes me to interesting places.

As a piano player, I can’t imagine retuning the 88 strings o my instrument.

That’s why you guys run the world [laughs]. We don’t like you keyboard players because of that. You’re in charge. Most Western music was thought up on the keyboard. We guitar players are kind of the back door [laughs]. But as a guitar player I was inspired by keyboard players. I listened to McCoy Tyner play a chord that had nine notes in it; it was like a tone cluster. I wanted that! I would listen to Gil Evans do that. I would listen to Bill Evans. And I would say, “Damn! How do I do that on a guitar?” I wasn’t a good enough guitar player to do it in regular tuning. But if I retuned the guitar, I got those kinds of chords. That’s why I went there and that’s why I stayed there.

New tunings do produce new emotional resonances.

There’s a magic to them.

Do songwriters have a responsibility beyond simply writing a good song, to also comment through music on our times?.

I don’t think there’s any responsibility to do it. I think there’s opportunity to do it if you care enough to do it. I don’t think you should feel compelled to do it. Nobody says you can only write love songs or you’re not really writing songs [laughs]. But if you’re a conscious human being and you see something like Kent State take place, then you’re going to want “Ohio.” That’s part of the deal. We need to always remember, though, that our main job is to [make you perky?], to take you on a little emotional voyage, to tell you a story. Our main job is not to be the watchmen. That’s just part of our gig.

Steve Earle once said he wished he didn’t have to keep writing topical songs. He wanted to get back to writing about love and baseball but circumstances didn’t allow it.

Well, he has the opportunity and he feels personally the responsibility to speak out. That’s not the only thing he does, by any stretch of imagination. He writes about everything.

Speaking generally, how has your approach to lyrics evolved to this point?

Well, it didn’t change for this record. But people fascinate me. More than anything else, i write mostly about love. But I do write about people because they’re just so interesting and so emotional.

I do occasionally feel the need to go back to my roots as a folkie. Part of our job is to be the town crier or the troubadour and carry the news. Every once in a while, if we see them shooting down your own children in America, you want to want to write “Ohio.” I wrote “Capitol” because I’m disgusted with the people in Congress. I doubt that there are eight people in there with a conscience. The rest of them are unbelievably, abysmally bad. And they’re doing a huge disservice to this country. So I couldn’t resist writing this song.

Generally, though, our job isn’t to preach at you. It’s to boogie and take you on emotional voyages. Generally, that’s what I like to do. If I can communicate anything interesting in the process, it’s a plus and I’m happy.

“Capitol” kind of took me back to “Long Time Gone” in this idea of making a blunt, direct commentary about things that anger or frustrate you about America today.

Well, here’s the thing. I’ve been trying to do that about Trump. I’ve been trying to write a song about what a disaster I think he is. I haven’t succeeded yet but I want that song so badly that I’ve actually gone on the Net and said, “Hey, you songwriters. We need a song. It needs to be an ass-kicker, another ‘Ohio.’ We need another ‘We Shall Overcome.’ We need a fight song. We need inspiration. We need to be lifted up, man. This is discouraging a lot of us. We believe in democracy and we’re watching it get sacrificed. It’s very tough.’ So, yeah, I want to write that song but I’m more than happy if somebody else does.

Music meant something significant during the turbulence of the Sixties. It feels like we’re entering a similar period, which may trigger some kind of similar artistic renaissance.

I share that exact view. I’ve been telling people that. One of the only good things to come out of this horrible circumstance is that it should generate a countervailing force. It should generate some really good art. The first sign of it I’ve seen is this song “Man in a Tinfoil Hat.” Donald Fagen and Todd Rundgren made this record. It’s hysterical! It’s gonna make you laugh for a week. You’re gonna want to call me back up and tell me how cool I am for turning you on to it. It’s wonderful. And it’s about Trump.

USA Today will premiere “Curved Air” with this story. The first amazing thing about that track is that the flamenco guitar at the top is actually your son on keyboards!

I wrote a really strange set of words. They’re about a guy getting blown up by an IED. The words don’t make that obvious; you have to really listen to the song to figure it out. But “curved air” is a blast wave. I sent them to James. Now, James is a consummate musician, probably one of the best musicians I’ve ever encountered in my life. He loves flamenco music along with the way he loves jazz and Indian music and all world music. He listens to it and he understands the structure. He understands how those guys are playing and in what time signature and where the emphasis should be and how the thing works. And then he does it on the keyboard. I don’t know how. I am completely flummoxed. When I heard it I said, “Who did you get to play the guitar?” And he said, “Me.” I said, “Oh, come on. You can’t possibly have played that. It’s not even conceivable.” But, yeah, he did it. He’s that good.

He wrote stunning music for it. If you listen to what the guitar is doing, in between the strumming parts there are picking parts. And if you listen to the picking parts, there are two or three melodies interweaving. It’s ridiculously musical! And beautiful!

This is the most complex song musically on the album. Were you worried that it was getting a little too outside as you were putting it together?

We just go with it. We’re into intricate, complex music. That’s just fine with us. We’re not trying to be pop guys, man. We’re not trying to have a hit. We’re trying to serve the songs and do the best music we can conceivably do. I don’t mean to whine or anything, but I’m at the end of my life. I’ve got a little bit of time left. And I feel a real strong pressure to do every bit of music I can conceivably do and do it the very best I possibly can.

Have you ever thought about posterity as you write songs?

No, I haven’t thought about it that way. The truth is, man, I tend to not think about my place in things or what is gonna come from my work at all. There’s a kind of a trap there where you wind up looking at yourself and going, “Gosh, I’m significant!” And I don’t want that. I want to do really good work and have other people say, “Wow, Croz is doing really good work.” But I don’t want to look that much at my work.

Have you thought about publishing your lyrics in print?

I would like to do that. I’ve been working on a songbook, which would give me a way to get the words out there. But I’ve also wanted for a long time to print a book of lyrics as poetry because some of them are pretty good. Some of them I think are excellent. I’d be really proud of it but so far I have not been able to do it.

This album has a lot of evocative visuals — the “towering sky” in “Home Free,” the “cavern open wide in the sky” in “Curved Air” and of course Sky Trails. Yet it all comes down to this intimate final track, “Home Free.”

It’s a great story, man. Here’s what happened. There’s a town in Connecticut where this woman lived in a little pink house. It was the biggest thing in her life. She loved it dearly. She was a nurse and she worked all her life to be able to have a house of her own. But the town took it away from her by eminent domain because a big pharmaceutical company was coming in and they bought up a huge lot. So the town took her house. She fought it all the way to the Supreme Court … and lost! They bulldozed it. And they never … used … the … lot. They never did a damned thing with it. They destroyed this woman’s life for nothing, only because they could.

A good friend of mine, a writer named Jeff Benedict, wrote a book about it called Little Pink House. Some other people decided it was too good of a story and they had to make it into a movie. So they did. Then he called me and said, “Would you write a song for the movie?” And I did.

I called James and said, “This is the story. How about it? You think we could write something?” And that’s what we wrote. They are now trying to get it nominated for an Academy Award.

You draw a broad range of ages to your shows.

That’s exactly what we try to do.

You’re privileged to be able to be fully contemporary and represent the past too. What is the difference between writing during today’s social upheavals and those of the past?

The big difference comes from writing more with other people.

You didn’t write collaboratively in CSN?

Occasionally it was a collaboration — like “Wooden Ships,” with Paul Kantner, Stephen Stills and me. But mostly it was a very competitive environment. Each of us wanted to have our songs be better than their songs. There are two types of efforts, man. There’s collaborative and and competitive. Competitive effort winds up in war. Collaborative effort winds up in a symphony orchestra. The more collaborations I do, the more I like them.

But the basic ethic behind how I look at the world hasn’t really changed. There are things I believe in and things that I’m definitely against. I try to celebrate the good stuff and call bullshit on the things I strongly disagree with — racism, sexism, war. I don’t have any problem sticking up for what I believe in. I never have. If there’s a purposeful edge to what I’m doing now, it’s to make good music.

There’s a difference between what you’re describing and what people sometimes call protest songs.

Well, that’s part of our heritage. We come from folk music, which comes from troubadours in the Middle Ages. It’s like the function of the town crier: “It’s 12 o’clock and all’s well.” Or “It’s 12:30 and you’ve elected an imbecile.” But that’s just a part of our job. It’s not the only part. The strongest thing we can probably do through music is to celebrate the best parts of humanity that we can find and to be a lifting force.

###

Hi, Robert. E.Z. Prine and I are both writing about music biopics, since there are so very, very many of them! David Crosby is interviewed in "Echo in the Canyon" which I wrote about in https://albertcory50.substack.com/p/echo-in-the-canyon