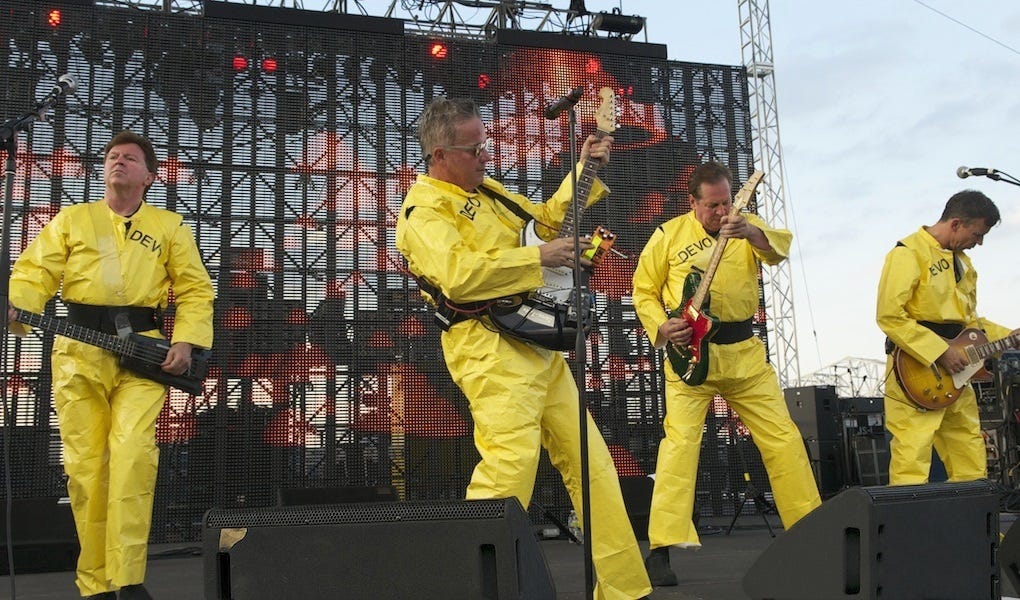

There were bigger stars on the scene in the Seventies, but none was more prescient than Devo, an unlikely lineup of collegiate nerds in jumpsuits and red flower-pot hats. Their mission was to destroy rock excess, something punk wouldn’t get around to doing until a few years later, and to replace it with a kind of music that reflected the anxieties of the modern world without lapsing into incomprehensible avant-gardisms. Their weapons were a pounding beat, a fascination with technology and a gift for merciless metaphor. Their songs paraded absurdities – potatoes, Marlboro hunks, whip-snapping weirdos – in tight formations that signaled discipline rather than psychedelic chaos. The future, as they saw it, was little more than a continuation of the ominous grind that had already reduced us from simans with some potential to money-hungry androids.

Mark Mothersbaugh, his brother Bob Mothersbaugh, and their colleagues Gerald V. Casale, Bob Casale and Alan Myers, put the band together as students at Kent State University, just after the National Guard’s attack on student antiwar demonstrators. The resulting massacre reverberated through youth culture. At Kent, though, the proto-Devo guys took this as their cue to put on bizarre costumes and start preaching an obscure philosophy drawn from a book, In the Beginning Was the End: Knowledge Can Be Eaten. As aggrieved young boomers railed against President Nixon to strains of folk and/or rock. Mothersbaugh and company sang of happy Mongoloids, accompanied by sputtering electronics and jerky beats.

The world eventually took notice. Buoyed by praise from David Bowie and Iggy Pop, they released a short but influential string of albums, until they got into hassles with record labels and dropped from sight.

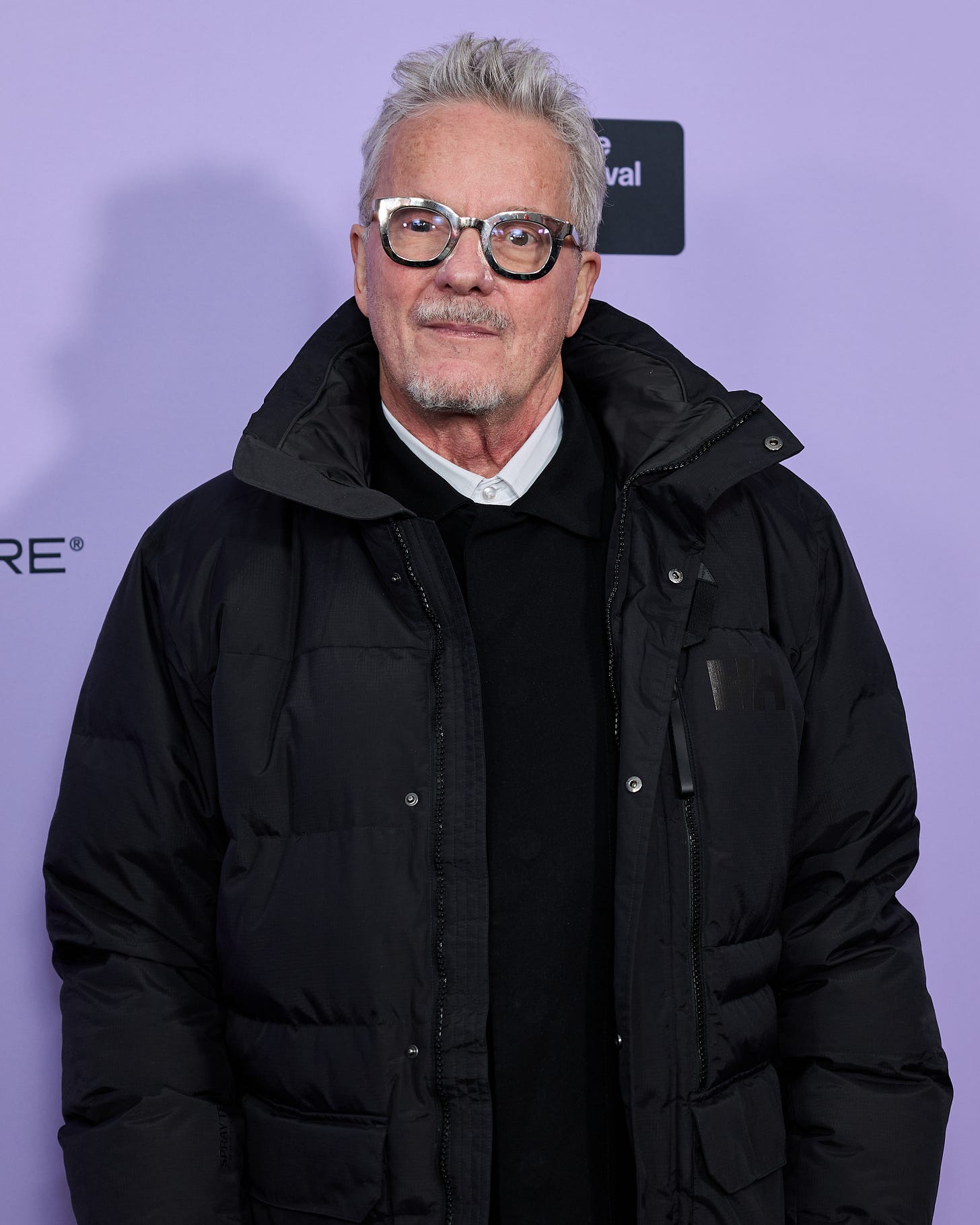

Well, not entirely. The key Devo players kept working together under the umbrella of Mutato Muzika, a firm dedicated to creating music for film, TV commercials and video games. Mark Mothersbaugh in particular contributed significantly to the zeitgeist: His music for the visionary “children’s” program Pee Wee’s Playhouse, marked a transition in the raw Devo sound into something that managed to be palatable to Middle American kids and their parents without losing its subversive edge. After that he scored Rugrats, It’s Pat, Bottle Rocket and other projects. When he and I spoke by phone for the Allmusic Zine, The whirs, ticks and clinks of his music was already embedded into the mainstream. Once described by Rolling Stone as fascistic, his work became familiar and assuring to dads and moms throughout Middle America.

If that isn’t a textbook example of de-evolution, you tell me what is.

****

What can you recall about their neighborhood where you grew up?

Akron, Ohio, in the early Seventies, was still the rubber capital of the world. You would drive through certain areas and smell of vulcanized rubber in the air. It has a climate very similar to England, since we were just below Lake Erie, so when we got the winds coming down off of Canada it would quite often pick up a lot of water from Lake Erie and turn it into snow and dump it on us. It was very overcast. As a matter of fact, when we first went over to Europe … We had independent singles that were actually hits in Europe before they came out over here, so when people said, “Akron? What’s that?,” we were like, “Well, it’s like Liverpool: dark and gray and overcast all the time.” It’s a factory city. The snow turns black once it touches the road.

So Akron was like England but without trendy punk angst.

Well, I don’t know if that still applies, because I haven’t lived there for a good fifteen or sixteen years. I’m starting to go back now and then, though. But its nickname back then was “Little West Virginia” because so many people between World War I and World War II migrated out of West Virginia and the coal mines of Pennsylvania to Akron. So it was kind of an urban hillbilly town.

Your family had a home organ. Was that instrument important in defining your idea of musical sound?

Yeah, very much. As a matter of fact, I viewed that organ as an instrument of torture. I thought that music was invented just to make my life difficult. I would sit there for organ lessons that I hated, with an organ teacher who warbled out of tune sitting next to me and banging her bony finger on the page while I played.

But what about the sound itself?

Actually, it came full circle. When I started collecting electronic instruments in that time period, I started hearing those sounds again after escaping from my parents’ living room twenty years before that. It kind of took me back to the days when I was sitting there with Ronnie Wyzinski, my grade school friend who had an accordion. We’d just bought the sheet music for “A Hard Day’s Night,” and we were sitting there, trying to play it on this wheezy organ and a beginner’s accordion. We were trying to figure out why we didn’t sound like the Beatles. It took us a couple of weeks before we realized that we’d spent our lives studying the wrong instruments. At the age of twelve we became very morose and suicidal over the fact that there was this incredible music out there that we couldn’t be part of because we learned the wrong instruments.

Roots

The sound of Devo seemed to have no precedent. How did it evolve?

[Awkward silence.]

Actually, excuse the word “evolve.”

No offense taken. I know what word you meant; you meant “devolve.” But people make that mistake often. In some ways, all words are equally useful in describing the phenomenon of de-evolution. But anyhow, I think a lot of it had to do with … We were going to school when we started the band. Jerry Casale and I were going to Kent State. We were protesting the war in Cambodia on campus – So was my brother Bob; he was a little high school kid who would come up and protest too. Then they shot a bunch of people while we were there and closed our school down.

That spring, we were writing music. We were hearing music everywhere. There was not anything called “sound design” at the time. I think that we were seeing that technology, besides creating instruments that were called instruments, it was also creating sounds and noises that were more integral to our culture and to where we came from. Jackhammers and windshield wipers and zippers were just as valid as the stuff that was being marketed and sold at Akron Music Center.

In fact, didn’t you pretty much dislike most of the music people were listening to at that time?

Well, you know, we started writing music together in 1970, the four of us. We saw what was happening after they shot people at Kent State. We saw our region, and probably most of the nation too, kind of go into a big sleep. It was like, the hippies and yippies rebelled, then they went, “Oh, crap. This is a little too real for us.” Then everybody went to sleep. The Republicans started building for the next onslaught. We had a Democrat come back again, then the Republicans got in there full force. But we saw the music that was happening in the early Seventies as being … The two most popular musics were disco and concert rock, and concert rock – Styx and Foreigner and Boston – was just a turnoff for us. … We were kind of bored with rock & roll. We were reading in Popular Science that there were these things called laser discs that everybody was going to own in a few years. So we made the connection that pop culture is going to take a big jump forward, and rock & roll is gonna disappear because sound and vision is going to supersede it. In the early Seventies, we were already predicting an MTV.

Our biggest error was in predicting that music television would kill rock & roll and expose the Emperor in his new clothes and would allow a new breed of artist to spring forth. What happened in reality is that the people who control music television became co-opted by the record industry. They just did payola and allowed dinosaurs that had no reason to be making videos to prop up their sagging careers.

Devo Debuts

When did Devo play its first gig?

The first gig we played, we called ourselves Sextet Devo because it was at a jazz and creative arts festival on campus at Kent State. I think they gave us something like fifty dollars, or maybe we played for free, I’m not sure. Jerry and I had been writing these songs. We paid a drummer to play with us, who swore after the show that he would never do that again because it was too embarrassing, because our music wasn’t up to his professional standards, given that he played in a covers band that played in the bar area around Kent. He felt like he had a reputation to protect and didn’t want to be associated with anymore after that show.

What year was this?

It was 1972. Chuck Statler, who was a friend of ours and a student at Kent State, showed up with an early video camera that was black and white, with reel-to-reel half-inch tape. It had the visual quality of, like, a 7-Eleven surveillance camera. So the funny thing is that our first performance was actually videotaped.

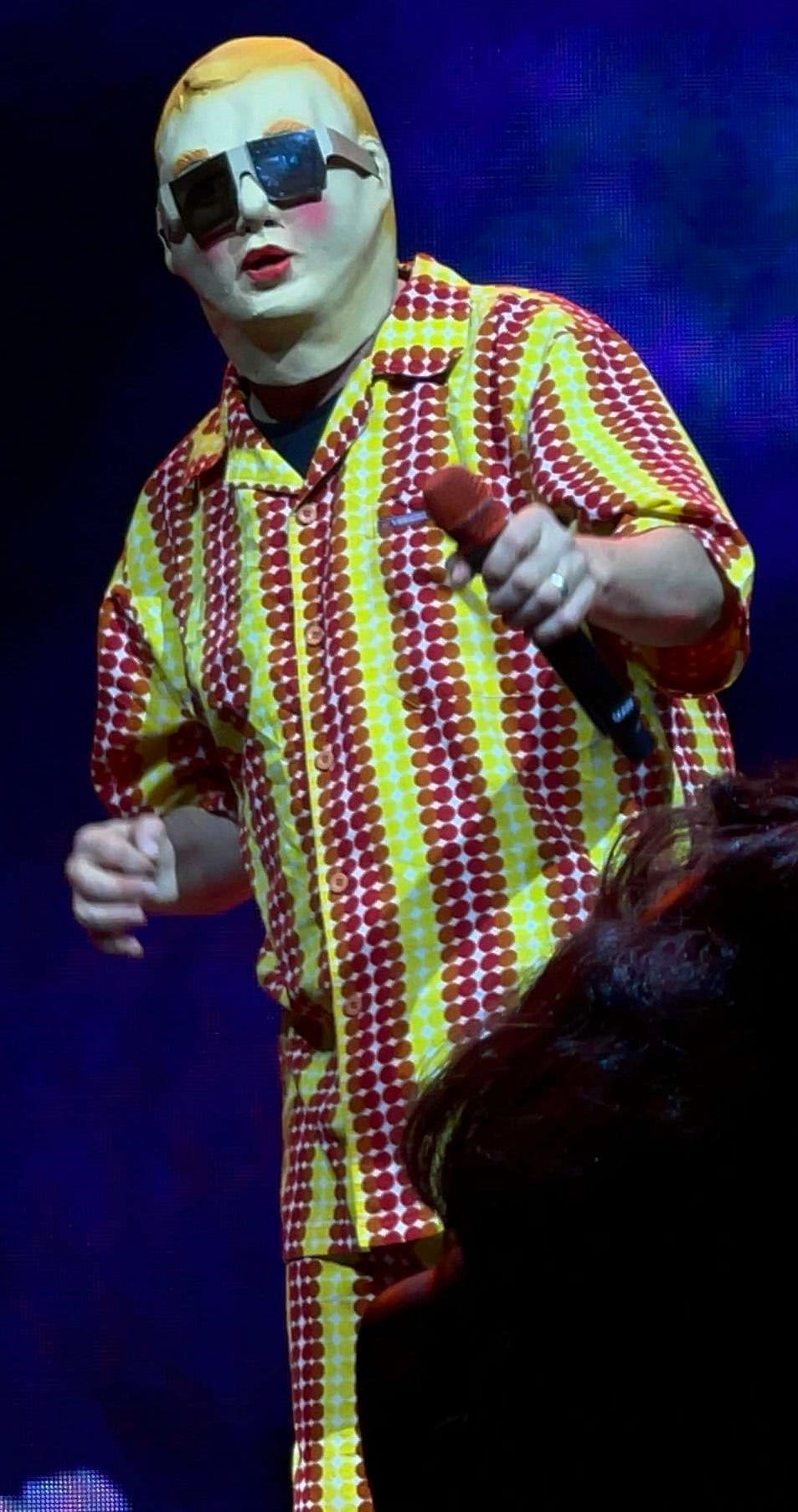

What were you wearing?

We had costumes. We were characters. We didn’t have any money. We couldn’t afford drugs, so we didn’t really fit into Akron because that’s pretty much the three areas of recreation that were available at that time. So we had masks and we pretended we were characters and took on personalities. I was wearing a full-head monkey mask and a lab coat.

Did this video pretty clearly forecast what Devo would eventually become?

There were a couple of songs that lasted through the years. I think we played a song called “Be Stiff” back then. But everything was much slower and more hard-core. It was very, very hard-core as far as being very sparse. It sounded like strange Chinese blues progressions matched with sequenced John Cage. My interest in electronics came from the inside of the instruments. We would experiment with our instruments, and when we broke them we’d oftentimes try to avoid fixing them, so that we could get the same sound over and over again that the broken synthesizer would do, that you couldn’t get from one that was in good condition.

That’s kind of the opposite of Brian Eno’s approach to working with broken gear. His interest isn’t in the instrument locking onto one defective sound but rather in its becoming harder to control and more random in what it produces.

I think it’s actually quite similar. We both wanted to be at the same place, and that was finding a new voice for an instrument. The makers of it had preconceived ideas of what you should do with it. All the early synthesizers sounded like glorified organs, really. People like Rick Wakeman and Keith Emerson kind of proliferated that myth because they played, like, classical music, just with slightly different sounds. We were saying, “You know what? Fuck all that. Those things are capable of making the sound of a V2 rocket or a mortar blast or the sound of skin being peeled off of a body.” That interested us more than sounding like a Dr. Seuss pipe organ.

Your interest in de-evolution seems to have come from a kind of a cerebral game, which transformed into something more serious after the Kent State shootings.

Well, it changed our lives, that’s for sure. And it helped create the band. We didn’t really have the band Devo before the Kent State shootings. We were looking for a way to describe what we saw going on in the world around us. Technologies were sprouting up left and right, but yet the quality of life was deteriorating. De-evolution was a word we used to describe what we saw as the condition of man on this planet.

But you never took the Neil Young “four dead in Ohio” approach in addressing these concerns.

Because we weren’t on the outside looking at it. We were right there when people were shot. We were in the middle of it. I remember the FBI showing up, four guys who looked like the Blues Brothers pulling up in a black Plymouth, like a government car, up our driveway, getting out and freaking my mom out by showing her pictures of my brother Bob burning a flag while firemen were trying to put out the ROTC building in flames at Kent State. [In mother’s voice:] “What’s he doing there? He’s only a sophomore in high school! What’s my baby doing at Kent State?”

Strange Collaborations

Your father was involved in some of the early Devo shows.

He was an active part of Devo from the beginning. It was one of those situations where somebody said, “I don’t want to be connected to you guys. What you’re doing is weird. I’ve got a reputation! I’m an up-and-coming lawyer in Akron, Ohio!” At the last minute, he backed out of being Generalboy in our very first film, The Truth About De-Evolution – you know, the fictitious head of Devo Inc. and the De-Evolutionary Army, and Booji’ Boy’s dad. My dad stepped into it and, strangely enough, it struck some nerve in him. It’s like, he suppressed his artistic desires when he was younger, because of the Depression and World War II. He got married right after World War II and started having kids immediately. So he became a salesman and was always trying to make sure there was bread on the table. So he totally got into the part of Generalboy, to the extent where, on our first tour, we were playing a hockey arena in Minneapolis, and some security guy came up and said, “There’s a guy out at the back door, dressed in an army outfit, who says he’s Generalboy. And he wants to introduce you guys onstage tonight.” We’re like, “What?” But he had driven from Akron to Minneapolis. He was in a number of videos. He reached his peak when, somewhere around New Traditionalists, he co-wrote a song. We ended up using one of his lyrics, called “Enough Said.” So he was one of the few people we ever collaborated with on a Devo song, the other being John Hinkley Jr. Those are the only two guys we ever co-wrote songs with.

Of course, what you did was to take some things that Hinkley had already done …

… and adapt to it, yeah. As a matter of fact, William Burroughs sent us lyrics and we did write a song with them, but whenever recorded it.

Have you thought of looking over some of Theodore Kaczynski’s writings as a source for lyrics?

Well, you only want one guy who’s attempted to assassinate somebody. I don’t want to make a career out of that. I liked the ironic nature of Hinkley’s lyrics, which were so heartfelt. They were Barry Manilow-esque. We thought, “Wow, the only thing that separates him from a career as Engelbert Humperdinck’s ghost writer is that fact that he acted on his impulses. …

Music Biz Casualties

How does the album business differ from the soundtrack business?

Well, that’s like comparing boogers with vomit. Devo, we were angry young men. That was our big statement. I think that most artists, even though they claim to reinvent themselves, Bowie and people like that … Your first statement as an artist, both a video or an audio artist, is usually your big statement. Everything else is permutations of a theme. Whether it gets better or becomes more focused or more commercial or stranger, you usually make the statement about who you are and what you’re about early on. If I could wish it on people, I’d say, “Yeah, be a rock star.” We were rock stars for, like, three minutes. And that was cool. Everybody should try it for three minutes. It’s fun. I only feel bad for people who try it and become addicted and can’t get off it. They spend the rest of their lives being miserable, trying to get there again.

So in fundamental ways, being a soundtrack composer can’t really compare with being a rock star.

It’s hard to compare them. Spinal Tap is the greatest rock & roll film ever made, only because it is more honest than any other rock & roll film ever made, including Woodstock or Monterey Pop. Spinal Tap is so realistic about the Larry, Curly and Moe nature of rock & roll and the music industry. It’s nonsensical. It’s frustrating, if you’re in it and you’re not a complete nitwit. It’s a sexy septic tank to swim around in; it’s got seductive powers.

And ultimately it confines performers in the trap of audience expectations.

Oh, yeah. You know, our first couple albums we did on Warner Bros., we were below the radar because we sold, like, a quarter-million records. They would say, “Oh, yeah, we have Captain Beefheart, we have Frank Zappa, we have Devo, and we’re not just about Madonna and Prince and Bob Seger.” They would throw our names out to show that they had taste. We were fine with that; they left us alone until “Whip It” accidentally became a big hit. After that, it was downhill. They’d show up at the recording studio and go, “Hey, you guys! Do anything you want! Whatever you want. Just do another ‘Whip It’ somewhere in there.” And we’re like, “Well, we don’t even know how we did that.” It wasn’t a plan, you know?

…

[So] we got boxed in. We looked more and more like a thinned-out version of the last album we’d done, because that’s what record companies would support. All the experimentation that we were doing, it’s kind of strange to go back and listen to it, because there’s elements of new age in our older things, there’s elements of hillbilly punk, there’s elements of trance-style dance music and industrial things that were much closer to what Nine Inch Nails and Nitzer Ebb ended up doing that what we put out on vinyl. We had forces that were pressuring us to do something, that had preconceived ideas of what we were about. At a certain point, we just had to say, “You know what? We do what we do. And some of it nobody’s ever going to hear.” I mean, most of the music we’ve ever done is on tapes in the basement here in this building. You don’t release everything you do, unless you’re … Sting, I guess [laughs].

A lot of the elements you’ve mentioned – the hillbilly punk, for instance – stem from how you use guitars in different contexts. “I’m a Potato,” for example, is kind of a riff-driven blues guitar piece, and “Midget” has an old funk feel.

Now, Jerry and my brother Bob were both very blues-oriented. Before we did Devo, Jerry was in a blues band and my brother was in a band that was doing almost Southern rock. They were doing Rolling Stones-type material, although they were writing their own stuff. My brother, his singing style was really similar to Mick Jagger. And I kind of came more out of Tangerine Dream. I was interested in elevator music and soundtrack music and TV commercials. I liked all that weird, fucked-up pop culture stuff that was, like, horrible and humorous and interesting all at the same time.

…

A Night with the Rolling Stones

How did you, of all people, wind up playing keyboards on a Rolling Stones session?

What happened was, in 1981, Devo was recording New Traditionalists. We were at the Power Station in New York City. It was cheaper to record in the evening than in the day, so we had a block where we were recording every night. We would come in at, like, seven in the evening. I forget who was there during the day; it was some funk band or somebody. They would leave and then we’d come in, and we’d booked it for all night. Aerosmith was there, doing an album, and I felt really bad for them because I was like, “Oh, those guys should really quit [laughs].” This is that time when they weren’t very popular and were still struggling to keep it together. And the Rolling Stones were in another room.

So this old man came up and stumbled into our studio at, like, two or three in the morning. He was like, “Hey, will one of you guys come and play on my album?” I’m looking at this guy: He’s in this big old sweater, he’s got gray hair and he’s kind of mumbling. And I’m saying, “Oh, my God! That’s Charlie Watts” So I said, “Sure!”

They had this track that they’d recorded in England in 1968. Bob Clearmountain was working at the console. They wanted to add a few instruments to it, because it was just the band playing. So I worked with Mick Jagger and put a keyboard track on it.

What was the song?

“Worried About My Baby.”

Was that just … really weird?

I was numb the whole time I was doing it.

It seems so contradictory to your whole artistic direction to be jamming with the Stones.

It was wrong, but at the same time it was the one chance in my life to be a groupie, because the first song we ever covered was “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” When I was a kid, I bought that song and listened to it ‘til the vinyl turned gray. I’d hear it five hundred times: the same song, over and over and over and over again. You’d just immediately start it up again when it was over. I remember one church woman saying to my mom [in hectoring, shrill voice]: “Mary? You’re letting him listen to that? That’s a dirty song!” And I’m like, “Really?” I got really excited. Now I’m listening to it really hard, because I knew she meant dirty like sexual or something. I was trying really hard to figure out what the hell it could be.

You were trying to break the code.

Yeah! So Devo was rehearsing in this car wash. It was in the middle of winter. They had no heat and we were freezing. Bob Casale started playing this little riff [articulates staccato figure] on this guitar, and everybody kind of fell into it with a part. Jerry tried to sing “Paint It Black” over it, but it didn’t really work. Then I started singing “Satisfaction” and it all fit.

Had you met Jagger before that night at the Power Station?

One time. It was, like, 1976, in New York City. We went to [Rolling Stones manager] Peter Rudge’s office and asked permission to record their song. They said, “Swell, let us hear it.” We played them the independent single we’d done – and Mick Jagger walked in and started dancing around the room, saying, “Yeah! I like that!” He knew who we were! He said, “Yeah, you guys look different in person than you do in your pictures with those outfits on.” I was like, “Mick Jagger has heard of us!” I was stunned.

Five years later, I’m sitting in a recording studio, Mick Jagger’s smoking my girlfriend’s pot and I don’t care. It was like I was in a dream world. I don’t remember much about it; I just remember how unbelievable it was.

…

An Eerie Premonition

Not long ago, the Kansas state board of education made it illegal to teach evolution in their schools. Your thoughts?

Well, it’s funny, because I used to invite the Jehovah’s Witnesses into my apartment in Akron because they’d give me these really great pamphlets – Awake!, and The Watchtower – that were always filled with anti-evolutionary information. We could always find things in there that we could use for Devo [laughs]. Now, I think there’s a lot of things they should quit teaching in school, but our biggest problem is that they’re not teaching anything in most of them. Out here in California, it’s really a problem. L.A. is a total mess. It’s shameful, because it’s not like the city doesn’t have money.

But in Kansas, they’re talking about actually wiping out any public school discussion of a subject.

That’s pretty insane. I think they should teach alternate concepts, without a doubt, and not necessarily any of the religions that are popular right now [laughs]. We have to go back to find some of those obscure Scandinavian and Central / South American religions. Did you ever see the movie Inherit the Wind, with Spencer Tracy?

Sure.

There’s a section in it I didn’t see until about four years ago, when somebody brought it to my attention. I can’t remember his name, but the guy who’s like the Pat Buchanan lawyer who’s representing the religious right …

That’s Frederic March, as William Jennings Bryan.

Yeah. There’s, like a sideshow at the courthouse. A barker has got a chimpanzee that’s got some clothes on, sitting on a podium, and there’s a sign behind it that says, “Is this your uncle?” And then it says, “Was man created by God or evolution?” That’s an unbelievable moment. If you watch the film again, you’ll never forget it. For about fifteen seconds they do a closeup of the monkey. And when they do, they cut off the first two letters of “God,” the monkey obscures the word “or” and the word “evolution” is cut off at the “o.” So on one side of the chimpanzee is a D, and on the other side is an E-V-O.

So they’re asking, “Are we not men?” And the chimpanzee was there with the answer.

And it predated us by a good twenty years.

####

I loved Devo.