I can’t claim credit for the idea of doing a simultaneous phone interview with these two singular artists and personalities. But I remain appreciative that Scott Crawford, editor of Harp, a magazine I had hopes in picking up where Musician had left off.

Even before we connected by conference call I knew that I was almost incidental to the process, that these two would take the ball and run further with it than I could have encouraged them to do on my own. In fact, McKay kicked off the conversation before I could say a word, with a question I myself would never have thought to ask. It was the perfect way to begin.

I spent much of the next hour or so listening and loving what transpired between these two. Of course I kept track of the conversation and jumped in now and then, but I allowed myself a little more time to replay the only time I had seen Eartha Kitt in person. I had spent a couple of hours in Bemelmans Bar at New York’s Hotel Carlyle, listening to pianist Peter Mintun play incomparably, as he always does. As I bade him a good night and left into the lobby, I could see into the supper club, where Kitt, in a glittering gold gown, was hitting the high, final note of some song. I couldn’t hear it but I could see her, head back, eyes closed ecstatically, arms thrust skyward, as the audience stood and rapturously applauded.

That picture is etched into my mental image file. But so is the cover to Nelly McKay’s 2004 debut album Get Away From Me, whose name was a wonderfully acerbic jab at Norah Jones’s chart-melting single “Come Away With Me.” There she was, all of 21, in a red jacket and hat, arms above her head and on her face a smile that was both bewitching and uncertain — an ironic complement to the title.

Even with their 55-year age difference, McKay and Kitt were a perfect match, each a product of cabaret and theater, having created public images that were both sexy and a teasing sendup. So this conversation was more than inevitable; it was necessary. I was lucky to just be there as it happened.

***

McKay: I really want to ask Miss Kitt what Orson Welles was like.

Kitt: Scary. He was wonderfully scary. He had so much on the ball. He was a great interpreter of words. We used to go to lunch. I was the only woman there; it would be Michael MacLiammoir, Hilton Edwards, Orson, and me at Calabados’, which in 1950 was the most famous restaurant in Paris, particularly among the theater people. [Note: MacLiammoir and Edwards were a gay couple who opened the Gate Theater in Dublin in 1928 and often invited Welles to perform there. MacLiammoir played Iago in Welles’ film version of Othello.] We always had a huge lunch. Orson would start with a cordial to stimulate his appetite, and he, Michael and Hilton would have a seven-course meal. And after each sip of whatever they were drinking, they’d get up and recite Shakespeare or Plato or Camus. It was so wonderful to be in their presence that I never said a word.

I think that was one of the reasons why he thought I was the most exciting woman in the world: I knew when to keep my mouth shut. And I was always considered very intelligent. I mean, look at his films – even that stupid thing of his that I saw on television because they’re doing a lot of documentaries now about the geniuses who were thrown out of Hollywood because they were maybe too intelligent, the writers and directors and all these people who had something in depth to say, be it pro or con to what was going on at that time. They were thrown out and considered Communists or whatever it is. So a lot of these really intelligent people had to go out and make these crazy films to get money. The stage was their love. And they always wanted to exercise this intelligence about themselves – but you cannot communicate with everybody who want to just make money. That’s what Hollywood was to them – at least that’s what Orson said. But you want to give people food for thought, so that when they leave the theater they’ll remember what you said. It may not be more than one or two words in your song or even in what you say. In those days it was very difficult, just like it is today, to put your philosophy down on celluloid and be appreciated for it.

But I had a lot of fun with Orson Welles and people like James Dean and Marlon Brando and with Hilton Edwards at the Gate Theater in Dublin. We very rarely had to talk to each other because once we said something to one another, it stimulated another part of the brain, and that brought on another side of the conversation. This is what we’re not doing today: We’re not stimulating each other’s intellects. We’re just watching television and thinking about what somebody said a hundred years ago, but not what somebody said yesterday. People today are against this and that; everything is negative but there’s nothing positive. We don’t converse with each other anymore. We stimulate each other’s minds. We seem to be so afraid of talking about religion or talking about politics or talking about our next door neighbor. But we talk about negative things because that seems to be the most commercial thing in the world. Look at the ratings on radio and television; everything is negative.

But as entertainment media grow more interactive, doesn’t that suggest the potential for a more stimulating and dynamic relationship between performers and audiences?

Kitt: That’s why entertainment is so important. At least we’re talking to one another live, instead of just sitting here, watching a box.

You two first met at a Woody Allen tribute concert in Chicago.

Kitt: Yes.

McKay: We sang a song [“You’re Either Too Young or Too Old”] that Miss Kitt hated [laughs]. It was one of the highlights of the show when she said that to the audience. It was wonderful.

How did you wind up with a song you didn’t like?

Kitt: I think it’s because [music director Dick] Hyman wanted us to sing this song together. He chose the whole program, so he gave each one of us the songs that we sang. Right, Nellie?

McKay: That’s correct, yeah.

Kitt: He wanted us to do a duet together, so they gave us this song that I can’t stand [laughs, then sings in kewpie-doll mimicry]: “You’re either too young or too old …” Oh, goodness gracious me! As far as I’m concerned, it degrades the young and the old. It was at wartime, and all the boys were off at the war, and all that were left behind were the very young and the very old. It’s not an insult to anybody, but I just feel uncomfortable singing it.

It must be hard to present material that you don’t like onstage.

Kitt: That’s why I said I didn’t like it. I said, “I’m not doing this very well because I hate this song [laughs]!” Nellie, it was very nice of you to have gone along with it, because you weren’t expecting me to do that.

McKay: Oh, no, it was wonderful!

Kitt: I was very glad to see that as young as you are, darling, you have a good sense of “hew-mah.” As a matter of fact, I think your life is going to be a lot of fun, because you sang those songs beautifully and you have a marvelous personality. Trying to get hold of you today, it took seven men to tell me how to get hold of you – one woman [laughter].

Nellie, how did you deal with whatever element of being star-struck you might have felt in singing with Miss Kitt?

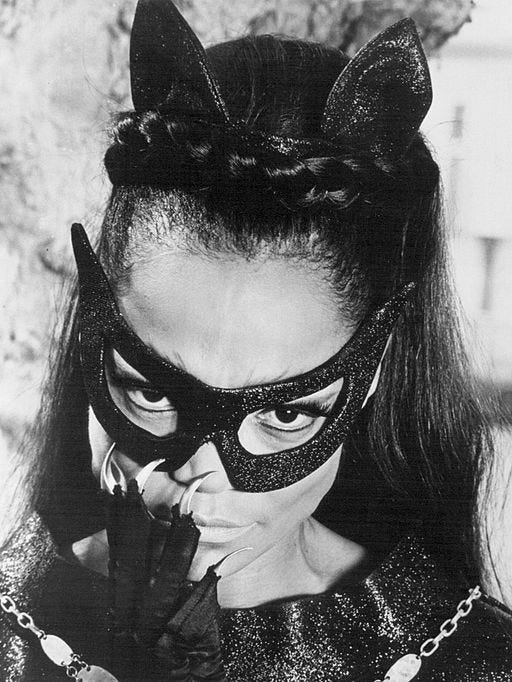

McKay: I just do everything her way. I grew up watching Batman, the TV series. I used to watch it every day after school, so that was a great influence growing up. Also, I have Rejuvenate: Never Too Late, and whenever I try to better myself I check that book.

Kitt: You gave me a feeling that you have a very positive feeling about yourself, without being overly positive, because there’s always a feeling of, “Can I do this?” You always try to do it a little bit better. It wasn’t a matter of having to know somebody, even for days. I know somebody from the minute I meet them. You see eye to eye, and therefore the acquaintance is already either positive or negative. And with Nellie to me, it was a very wonderful feeling. She sang before I did, and it gave me the feeling that this girl is going to be okay.

Each of you, in different ways, has to deal with the issue of audience preconceptions. Everyone who comes to see Eartha Kitt has a preconception of what they can expect from you. Can you work with that positively to put across a performance?

Kitt: To a great extent – I wouldn’t say one hundred percent – I work with it, because you have a feeling that even with the songs they’ve never heard me sing before, you have to have them realize that this is also a part of my program and let’s see whether we can get acquainted through this particular song. It usually works. Sometimes, if I sing a song that I feel they really don’t want to hear me in particular sing, then I delete it from the program because I cannot get into something that I feel the audience is not going to go with me.

Nellie, you’ve gotten a lot of press as an unpredictable, upcoming artist. Does that put you in a box too?

McKay: Gee, I don’t know. I find the road hard, and sometimes when I meet people after the show they’re very nice. But there is that thing of working toward pleasing people you don’t even know. That hierarchy between individuals isn’t just between celebrity and proletariat or whatever; it’s a question of attitude. It seems that, talking to people, I find that it’s high school all over again, and I become the geeky kid. I don’t try to make my audience too happy – I don’t set out to make them unhappy either, but if I think too much about what they want, I don’t think I could perform anymore.

Kitt: You have to learn from the audience. You have to feel that the audience is saying you’re okay with that particular moment, but then they want to see what you’re going to do for the next moment. You’re always auditioning for the interpretation of the next song or even your next moment within the song you’re already singing. I get a lot from the audience because they have always been my best directors.

McKay: You certainly don’t act like you’re auditioning. My mom worked briefly with Yul Brynner, and she said the same thing: When you come out onstage, it’s that command of the audience, the command of the situation. They’re not shying away from applause or adulation. It was just that total self up there.

Kitt: You give the audience the feeling, even though you’re on tenterhooks. That’s the way I feel. I’m never feeling that the audience is going to be on my side every minute of the way, because that’s not true. If one person gets up, or one person sneezes, I feel rejected [laughs]. You’re always going on what has happened and expecting to be able to conquer that, so when you leave the stage you know you’ve done as good a job as you could have done at that moment.

Reading the Room

You never lose touch with what’s going on in the audience.

Kitt: Definitely. I was doing the Litchfield [Connecticut] Jazz Festival, which was an outdoor, family situation. There was a beautiful little girl who decided to start dancing while I was singing. She was so adorable, but she was so distracting! I had to choreograph myself to tell her parents that this was not the thing to be doing, because in those cases I might forget my lyrics and start laughing to the extent that I’m out of the character that I set out to be in that song.

How do you deal with especially difficult audiences?

McKay: Usually the show just isn’t a success [laughs]. But a really aggressive, hostile audience can make me do a better show than a friendly, overly indulgent audience – an audience where you say “hello” and they laugh, or you could say “this is my next song” and they applaud. That’s fine, but I’m thinking, “I’m not being funny right now. Why are you laughing?” But especially when you’re opening for other people, if they ignore you and boo and get to the verge of throwing things, I find that a challenge and I perform better.

Your run-in with President Johnson over America’s involvement in Vietnam was a milestone in your career. Do you see similar issues affecting performers today?

Kitt: Well, no matter what our government does, some segment of the nation is going to be unhappy and they’re going to say so. But at this time we should be embracing the president rather than trying to knock him out of the box, because we are in a war and we are embarrassing the boys who are fighting for our freedom. We are giving them the feeling that we don’t appreciate what they’re doing. What are we trying to do? We’re weakening the country from the inside, and when you weaken the country from the inside it’s easy for the enemy to take over. So we’re knocking ourselves out when we just blurt out anything. The publicity is going against us in the hands of the enemy.

Now, when I took my stand against our involvement in Vietnam, it was because I was asked to come to the White House in order to give my opinions about why there was so much juvenile delinquency in the streets of America. I didn’t stand on a box, at a corner somewhere; I give my opinions when I’m asked. But I knew that the question from Mrs. Johnson was going to be the boys who had run away from the United States, not because they didn’t like America but because they thought that our position in Vietnam was incorrect and that it was an unwinnable and illegal war. And this is what I said: “Our boys feel that it is not right for us to be in Vietnam. That’s why they play the game to be bad, because the bad guys don’t go to war – the good guys do.”

Nellie, you deal with topical issues in your performances. Where do you draw the line between speaking out on one or another concern and entertaining?

McKay: That line is extremely blurry. The Sixties showed that you can provide entertainment while actually doing something about a given situation. That’s entertainment in and of itself. It’s fun to do something. It’s fun to challenge and change the system …

Kitt: You can’t change the system. You can change the president but you can’t change a monarchy.

McKay: A monarchy?

Kitt: Yeah.

McKay: Well, certain countries have gotten rid of their monarchies. I don’t really know why certain countries still have monarchies. They get paid a lot of money too.

Kitt: And they’re probably making suckers of the United States because we pour a lot of money into areas and we don’t keep track of that money, so we don’t know how it’s being used. We do that here too, because we should be taking more care of our schools and education. We put a lot of money into those situations and then we don’t see to it that the education is done in a proper manner.

Miss Kitt, you didn’t sing topical songs in your shows.

Kitt: I don’t believe in doing political philosophy on the stage. People pay money to come and be entertained. If you want to entertain them in a political way, then do it away from the legitimate stage. It’s not fair for the public to be under that kind of restriction. But if you ask me a question off the stage, in my dressing room, I will give you my opinion.

McKay: Well, I’m doing Three-Penny Opera on Broadway. That’s a great example of something that makes people think, but it’s in the context of the story and it has incredible music. It really is about things that affect everybody.

Kitt: Yes, that’s a very political one, and it’s a classic. Which character are you going to play?

McKay: Polly Peachum.

Kitt: [Sings.] “I was young, only just turned sixteen, when you came up from Burma to me.” Is that one of your songs?

McKay: Yeah, but it’s a new translation. I kind of like your words, though. Maybe we can change them.

Kitt: I sang that character for Lotte Lenya. There have been many translations, and they tell me that the translations I had were the better ones because they’d been more simplified. It’s like Showboat. That’s different, because if you do it as a show, people know what they’re coming to see and they know what they’re going to hear. But you don’t just blurt things out because that’s the way you feel and you want to preach to the audience when they came to hear you sing “Santa, Baby.”

McKay: I know a lot of feminists who will go to pro-choice rallies and marches, but in their careers – maybe they’re actors – they do things I don’t really consider feminist. They’re adapting to the system because they feel that’s what they have to do. They do what a lot of the men in charge of the movie studios and TV studios tell them to do. I don’t want that contradiction. My life work is to represent what I believe and not have them be two separate things.

Kitt: It is a separate thing in my position because everyone sees me as the entertainer with songs that I feel I’m capable of interpreting. My politics have nothing to do with me as an entertainer.

Public Images

What about the difference between your stage persona and who you are in real life? This distinction is may be blurring as well with younger performers, who are seen as being hyper-versions of their real selves.

Kitt: I never thought of myself onstage as being a hyper-version of who I am, but maybe that’s true from a psychological view, if you analyze me. Maybe Freud would tell me that’s what I do. But I do know the difference between Eartha Mae and Eartha Kitt. I don’t carry Eartha Mae onstage, although of course she’s always there because she has to remind me not to go too far with whatever Eartha Kitt wants to do at that particular moment. She has to keep Eartha Kitt’s feet on the ground, on and off the stage.

McKay: I just know that onstage I’m more obnoxious.

Kitt: Now, why do you say that?

McKay: Because you have a microphone and you have to be more in control of your facilities, as I think you are, and more precise with what you do. You know what you want to get across and you work to get it across, whereas usually I feel a little lost onstage. I’m not exactly sure where I am or what I’m doing there. I just feel like I come across as obnoxious.

Kitt: Well, that’s a healthy feeling, because that means that you are observing, now that you are thinking, consciously or not, about what is going on around you. You do want to be able to communicate with that audience in front of you. You’re growing. You’re trying to find a way to do that in a positive manner. So it’s healthy that you are, I would say, a little bit confused, because you have not become whoever it is that you’re aiming for yet.

McKay: Right, but do you ever feel that you’re Eartha Kitt but maybe you’d like to try being someone completely different? Do you get a little tired of Eartha Kitt sometimes?

Kitt: Well, now that I’m about to be eighty years old, maybe [laughs]. Actually, I never become tired of Eartha Kitt, except maybe for a time when something happens in the audience, when I hit a wrong note and didn’t sing the way I would love to, or the sound system isn’t right and you’re fighting that element. Then I say, “Oh, Jiminy Cricket, I’m going to get out of this business because it makes me too nervous.”

“I’ve never sung a risqué song in my life.” — Eartha Kitt

Do you look for songs to perform based on what you personally enjoy or on what the Eartha Kitt character would present well?

Kitt: I’m looking for songs all the time. We’re putting an album together now, which I hope to be out by my eightieth birthday, which is the seventeenth of January. I said to Bob Stone, whose company is helping me put this together, that I have to have songs that are meaningful. I have to be able to understand what the story is in the song and to interpret that story. And of course that story has to be something I feel, whether it’s dramatic or comedy. These songs are very difficult to find. Lots of times I get songs that are risqué, because they believe that Eartha Kitt sings risqué songs. I’ve never sung a risqué song in my life, but they say that even if I read the phone book, because of the sound of my voice, they’d think of me as a sex … thing. Of course, I understand that, so I play with it. I don’t think of myself as a sex symbol. Actually, it’s a joke to me, because my whole life has been a joke. I mean, my girlfriend dared me to go down and have an audition. I took the dare, and I won a full scholarship. The audience made me who I am, so I love to play with the audience, and I think the audience likes that too.

McKay: I like it when somebody offers a challenge because all those years of coming home from high school and watching Comedy Central have paid off. You can do your Paula Poundstone or whoever to deflect that. Some of the best moments are the spontaneous ones.

Kitt: Exactly. That’s what I feel. That’s why I can’t find people to write for me: They write things they think of as Eartha Kitt’s sense of humor, but everything I do comes out of the moment. Of course, sometimes I get offstage and I’ve already forgotten that moment. That’s why you have to find your own sense of humor, not somebody else’s; then you’ll be in the business for a long time.

What are the differences between interpreting other people’s songs and singing your own songs?

Kitt: I like songs that give a feeling that the writer has lived. “I’m Still Here” by Sondheim is one of the best songs I’ve ever come by. If someone sings that song, I have to feel that they’ve been somewhere. But there are too many young people … well, maybe they have been somewhere, but you have to feel that you’ve experienced something in that story. So I feel that people like Sondheim, like the Gershwins used to, like Cole Porter, always wrote meaningful songs. This is a problem today: Songs are not as profound, intelligent, or meaningful as they used to be.

McKay: Well, I like obnoxious songs, I guess. When you interpret a song, you’re trying to mirror the emotion of the person who wrote the song …

Kitt: Is that why you write songs? You’re mirroring yourself?

McKay: Yeah, it’s kind of creepy, really. I tend to write when there’s nothing better to do. Sometimes something happy moves me to write, but often it’s anger at a certain situation or it’s a sense of loss. Whether it’s being an entertainment personality, like you, as opposed to … I feel like you’re in a stronger position than a lot of other actors and singers who don’t have such a strong personality. And I feel like I’m in a stronger position because I write my own stuff. If you can differentiate yourself that way, you have more power.

Kitt: You’re writing about your own feelings, happy or otherwise.

McKay: Well, my own feelings, and sometimes the feelings of others. I think there’s such a thing as a national mood or even a neighborhood mood. You see the same things happening everywhere and you try to affect that.

Kitt: Why don’t you send me some of your songs?

McKay: Oh, thank you so much. I certainly will.

Kitt: I won’t make any promises [laughter].

McKay: I know. I’ve been repeating that thing you’ve said about not giving comps. I’ve been using that, let me tell you.

Kitt: Please call me Eartha … and send me a couple of your songs. Maybe I can invite you to sing on my album.

McKay: Oh, my goodness!

How do you keep focused on who you are and what you have to say as a performer, as your career takes you from smaller to larger venues?

Kitt: As far as I’m concerned, I’m still thinking in terms of that one light and talking to that one person. What I get from that feeling of talking to one person extends to the back of the house, no matter how big the house is. I don’t like to work in front of more than two thousand people, though, because then it’s a concert. The big arenas, with the big television screens that the artist can’t even see, with your facial expressions and all that, that’s circus time. I like the intimacy of being able to talk with and sing to people as though they were sitting in my living room. I used to do Madison Square Garden, which was like seven thousand people back in the Sixties. But no matter how many people were in the house, and it was always full, Mister Brown, who was our lighting and stage man, always made it an intimate situation, where everybody felt they were included. It should always be an intimate situation, no matter how big the place is.

McKay: I’m trying to become more careful, so you don’t just turn people out with something you say. If you can put it in a way that you’re still speaking what you believe to be the truth, but you say it in a way that doesn’t seem callous, like you don’t care about those people, I guess that’s my version of intimacy, trying not to either preach to the choir or preach to the majority but to put it in a way so that everybody knows where I’m coming from.

What exactly are audiences looking for these days? For all the changes in music since you broke into the business, are people hoping for the same kind of stuff when they come to your show?

Kitt: No, because they’re getting tired of the noise. They’re coming back to what they hope will eventually be … well, I don’t want to insult the media in any form or fashion, because we all have our positions, whether we think of it as an artistic point of view or just entertainment or a lot of noise, so we think that as long as we’re making a living and as long as we’re still here, everything is fine. But the audience in general is looking for quality now. When I say “noise,” that doesn’t mean that I’m saying there’s no quality in that. There is, obviously. But I’m talking about the quality we used to have as artists who could take an intimate cabaret feeling into a bigger arena without losing anything. As I said, you want to feel that you’re standing in just one spotlight and communicating with just one person.

As a member of the postmodern, more ironic era in entertainment, does that ring true for you?

McKay: Well, certainly, that intimacy is lacking from a lot of things, but also my generation stayed in the Sixties and Seventies. A certain amount of cynicism came into it. That was healthy, because people had been lied to. Now people are so used to being lied to that they feel like there’s no room for idealism anymore, because you’ll never get anywhere anyway. There are politicians, whether they’re on the mainstream left or the right, who all want a certain budget for the military. They’re all pro-war, to some extent. Sometimes people like to see entertainers because they hear what they don’t get from politicians. You never see someone saying, “I don’t think there should be any war,” on the news, but that’s a really pertinent message, and I don’t see why that’s any more inconceivable than hurting people.

####

Wow, Wow and Wow!! I reread this several times because of the fantastic conversation. I adore both women and their stories. Eartha Kitt is a national treasure. THE Catwoman in my opinion. I’ve loved McKay since her first album. What a respite from incessant dumpy trumpy nonsense. Thank you!