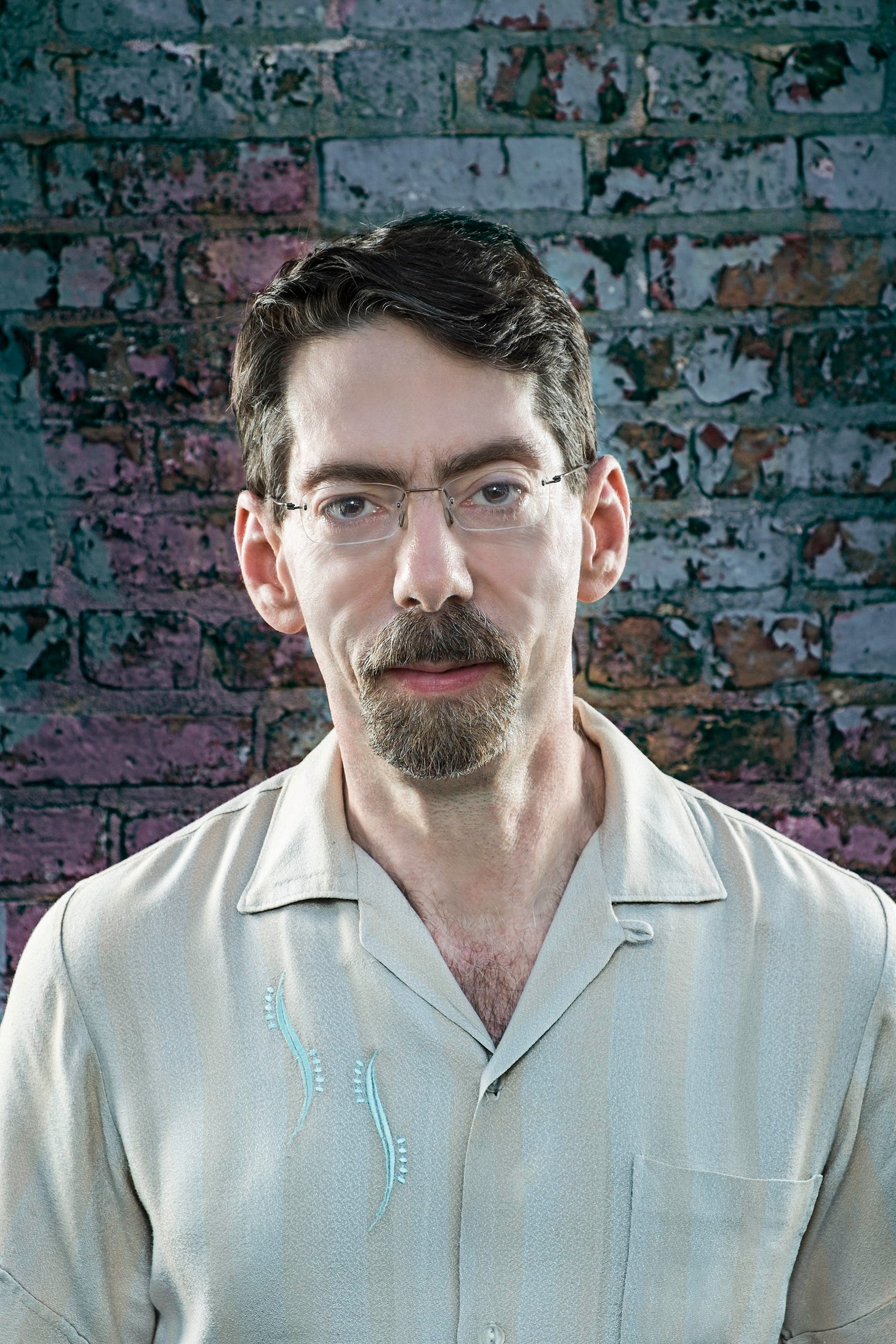

Fred Hersch

Allmusic Zine, January 2000

****

Improvisation is the most primal element in music. The baby’s cry, driven by need, unconfined by words, is as much a solo as a chorus from Lester Young. That same impulse will push the jazz singer into the sonic Dada of scat, where lyrics succumb to the purity of sound and rhythm.

This is why there’s something contradictory in the notion of talking about improvisation. Language itself seems to battle the process by its tendency to erect barriers and create rules. Some musicians deal with this the easy way: by being nonverbal.

Then there’s Fred Hirsch, whose ability to extemporize in music is tempered by intelligence and introspection. Whether seated at a piano or before an interviewer’s microphone, he communicates thoughtfully, in musical phrases or articulate sentences. In conversation, he listens and responds, building his idea with care. At the piano, his process functions more emotionally, drawing from concepts more cerebral than the ones found typically in jazz, from adaptations of French and classical repertoire duo recitals with the classical pianist Jeffrey Kahane.

When we met shortly before his solo recital at the Kerrytown Concert Hall in Ann Arbor, Michigan, all of this was on Hersch’s mind. Sunlight streamed into the intimate room as he sat at theSteinway and considered the magic of inventing music in real time.

****

How do you choose songs that work for you as an improviser?

I’d say I’m pretty idiosyncratic in my choice of material. When I’m dealing with a reinterpretation of a jazz composition by Monk or Billy Srayhorn or Wayne Shorter, often there are no lyrics, so I’m just attracted to the form, to the shape, to the harmony, to the way the chord changes move. I also play a lot of songs that have words. Words are an important way for me to get into a song. If I can sometimes connect with the words as well as the melody, then that gives me another element to work with.

I try to respect whatever composition I’m playing. If it’s a good composition, I’m gonna respect it. But I never want to be so reverent with it that I’m doing a cover version. I like to do what I call a creative reinterpretation of a song. I like to see how I can put my own signature on a song by way of an approach or an arrangement, whether that’s spontaneous or more played. There’s a lot of ways in for me, but it’s one of those things like, I kind of know it when I hear it.

Do you ever get tired of playing certain songs?

Sometimes there are songs that I maybe learned early on and as a jazz player I got real sick of playing. And now I’ve rediscovered them twenty years later and I find I enjoy playing them. So I think you go in cycles with material. Classical pianists say the same thing: Maybe they record Bach in their twenties. Then they come back to it in their forties. And then maybe they feel differently about it in their sixties. There’s always something new to be done with great things.

When you drop a tune from your repertoire, is it simply because you’re tired of it? Or has it somehow stopped stimulating your creativity?

A little bit of both. I think the analogy I might use in terms of talking about, say, why I continue to play standards … It’s almost like a glass bowl. A song has a shape. It’s rigid shape, thirty-two bars long or sixteen bars long, whatever it is. And this bowl, you can put anything into it. You can put peanuts into it. You can put M&Ms or marbles. You could put dirt in it. You can fill it with whatever you want. But the shape doesn’t really change. It’s like the painters who do landscapes and still lifes. I don’t think the definitive still life has been painted. Just like I think there’s room for another great interpretation of “Body and Soul” or Bach or anything else. These things are very doable. It’s about what we bring to it, how we connect to it. It’s not often even about technical things. It’s about feeling.

Classical performances are more about bringing a composition to life, whereas jazz standards are vehicles for artists to use in exploring their own creativity.

The material is a springboard. At different moments, I feel more or less inspired by different material. It also depends on who I’m playing with. I do a lot of solo concerts, so that’s one repertoire. I have a traditional trio, with bass and drums; that’s a different sort of repertoire. And special projects with other musicians, where we build our own repertoire that can involve a lot of things. I like doing all of it.

If the tune has an especially beautiful melody, though, does that affect how you might improvise on it?

Well, I like to play melodies. I had a very interesting experience with Jimmy Rowles many years ago — a great pianist and a wonderful, crusty kind of fellow. I was listening to him play at Bradley’s one night in New York; Bob Crenshaw was playing bass. I was sitting up close — you know, a young guy who was new in town. He knew who I was and he let me sit in a couple of times. He knew a million tunes and had great stories — a wonderful gravel voice. He played a ballad, just played the melody. Then he went to another ballad and played the melody. By the time he got to the fourth ballad, without playing any “jazz,” any improv choruses, he leaned over to me, because he could tell I was looking at him like, “Okay, where’s the jazz?,” and said [in hoarse whisper], “You know, sometimes I just like to play a melody.”

There’s something to be said for that. Sometimes I like to just play a chorus of something. And the jazz, or whatever you want to call the improvisation, is the harmony that I use and in the movement of voices and the way that I interpret the melody. I’d kist ;ole a great singer doesn’t really have to do much, except connect [with] and sing the song. There doesn’t have to be lots of wild scat singing or anything else; it’s about acting the song, delivering the song.

Is it easier to play a standard tune than to create your own material either through writing or improvising from scratch?

Playing standards or reinterpreting standard pieces, I don’t view it as any less creative than writing my own music. It’s just a different kind of creativity. To those who would say, “Yeah, he’s playing tunes,” just playing tunes is not easy. And the material does not have to be complex for it to be interesting, if the performer is engaged. That’s the quality that I need: I need to be engaged. I need to be comfortable but not too comfortable, stimulated by not overwhelmed, respectful but not reverent — just finding that balance.

Jazz improvisation is all about balance: If it’s too technical, then it’s dull. If it’s just emotion for the sake of emotion … It’s got to be thought but not too much and felt but not indulged. It’s very elusive. As soon as you think you sort of have it, it’s gone. For me, that always keeps it interesting.

“If you go into something with an open mind, then maybe you’ll be pleasantly surprised.”

How do you get ready to play a gig that involves a lot of improvising?

I usually do crossword puzzles backstage. For me, especially at a solo concert, I want to think about stuff as little as possible. I don’t really want to have a plan. If I take anything onstage with me for a solo concert, I might have a list of tunes that’s almost like a menu. I’ll take my first tune or two. Then I’ll start looking down the menu to see if anything pops out. Or maybe it kind of suggests something that isn’t on the menu. And I’ll play that, because it’s just me out there: I can do what I want. So I try not to think about it. I think this is true of life too: I mean, if you have an agenda, you’re most likely to be disappointed. If you go into something with an open mind, then maybe you’ll be pleasantly surprised.

The Opened Door

[At my request, Hersch plays “Shenandoah,” a song he remembers fondly from his youth but hasn’t played in many years. His performance is reflective but emotionally compelling, with the melody kept prominent through a series of reharmonization and a key change.]

Absolutely beautiful. What was going through your mind as you played this piece?

I’m hearing the words and the idea of maybe thinking of something different — you know, “across the wide Missouri” at the high end of the piano. There were times when I was sort of freely improvising around the melody without thinking about the form.

Did you let your improvisation carry you through the key change?

What happens is, you play along and things happen. It’s like a door: You just open the door and you go into another room. If you have an agenda, or if you’re worried about being correct, you won’t go through these doors. A lot of times, you know, I’ll play something that would be considered a mistake. Rather than panic, I go, “Okay, this is interesting. Let’s see where it goes.” And I’ll let it take me somewhere. I don’t want to control it. I don’t want it to get out of control either. So it’s a question of balance. I’ll probably never play that tune in the same way again; it’s just what I played at this moment.

How can a musician learn to unlock those doors and improvise?

I’ve always improvised, since I was a young child. When I was a little kid, I would improvise. But it would sound like classical music, because that’s what I listened to. I would play things that sounded like Mozart or Haydn or Stravinsky or Brahms, whatever I was interested in. Sometimes, even before I played jazz, I would take pop songs: Beatles tunes or James Taylor songs, folk songs, whatever. I would learn them by ear. Then I would sort of play them my way. I wouldn’t go to the music store and buy the sheet music. I’d use my own kind of chords.

Discovering Jazz

How did you move from that point into playing jazz?

I discovered jazz as a late teenager. It seemed to me … First of all, I thought it was really cool hanging out with adults in smoky places, staying up all night, things like that. But beyond that, I thought it was a great language, the closest we have to an improvisational language, where we can sit down with people and go, “Okay, let’s play ‘Autumn Leaves.’ Count it off.” And something will happen. It’s common practice: If you know the conventions and the basic tunes, you can get involved.

You know, there’s a lot of jazz being played now that’s, frankly, fairly academic, just like there’s a great number of classical players who can play the notes and not much more. It’s not really gonna inspire you or take you somewhere or be in any way transcendent or enlightening. I hope that when I play a song, people, if they’re open, might be able to hear that song in a different way or consider another interpretation. I would like to take people somewhere as I’m letting the music take me somewhere.

Do memorable recorded solos encourage audiences to prefer regurgitations of those solos, rather than having the artists try new things?

Yeah, and also, as jazz has become more of an academic subject — jazz education has become an industry and so forth — there is a sense of, “Okay, this is the correct approach.” If everybody listens to and learns from the same thirty, forty or fifty records, jazz is gonna become a dead art form.

What I bring to it, given my background and the kind of person I am, is important. We all need to be personal. You know, in the classical music world, the competitions winnow out many people with interesting personalities because they’re not perfect enough or accurate enough. I’m quite sure that many of our great concert pianists who had amazing careers thirty, forty, fifty or sixty years ago, wouldn’t be the people they pick to win these competitions. It’s gotten to the point now where, if you’re a competition winner, who cares? It’s like, what do you have to say? You’re a good player, but the next level is, are you an interesting artist? Are you going to do something that’s intriguing, that’s going to involve the listener, that’s going to make a person want to listen to that record again and again?

“You’re a good player, but the next level is, are you an interesting artist?”

It’s like they say about the secret of creativity: You make it up. There’s no answer, you know? If I knew what the answer was, then there’d be no point in doing it. The role of the artist, or the role of the person who’s creative, is to continually search for these things that are elusive. If you know what you’re gonna play on the fourth chorus of an improvisation and you’re only on the first chorus, well, you might as well sell insurance.

Why?

Because you’re not taking into account how you feel that day, or the instrument you’re playing, or the other musicians you’re playing with. The bands that I play with, I want them to surprise me. I don’t want it to be anarchy up there; it should be focused. But, hey, things take off in a different acoustical environment every night. It’s a blessing and a curse, but every night I have to play a different instrument. They’re sometimes better or worse, and they make me play differently. I could look at that as a bad thing. Sometimes I do, but I try not to. I try to say, “Okay, this is just gonna be different.”

###