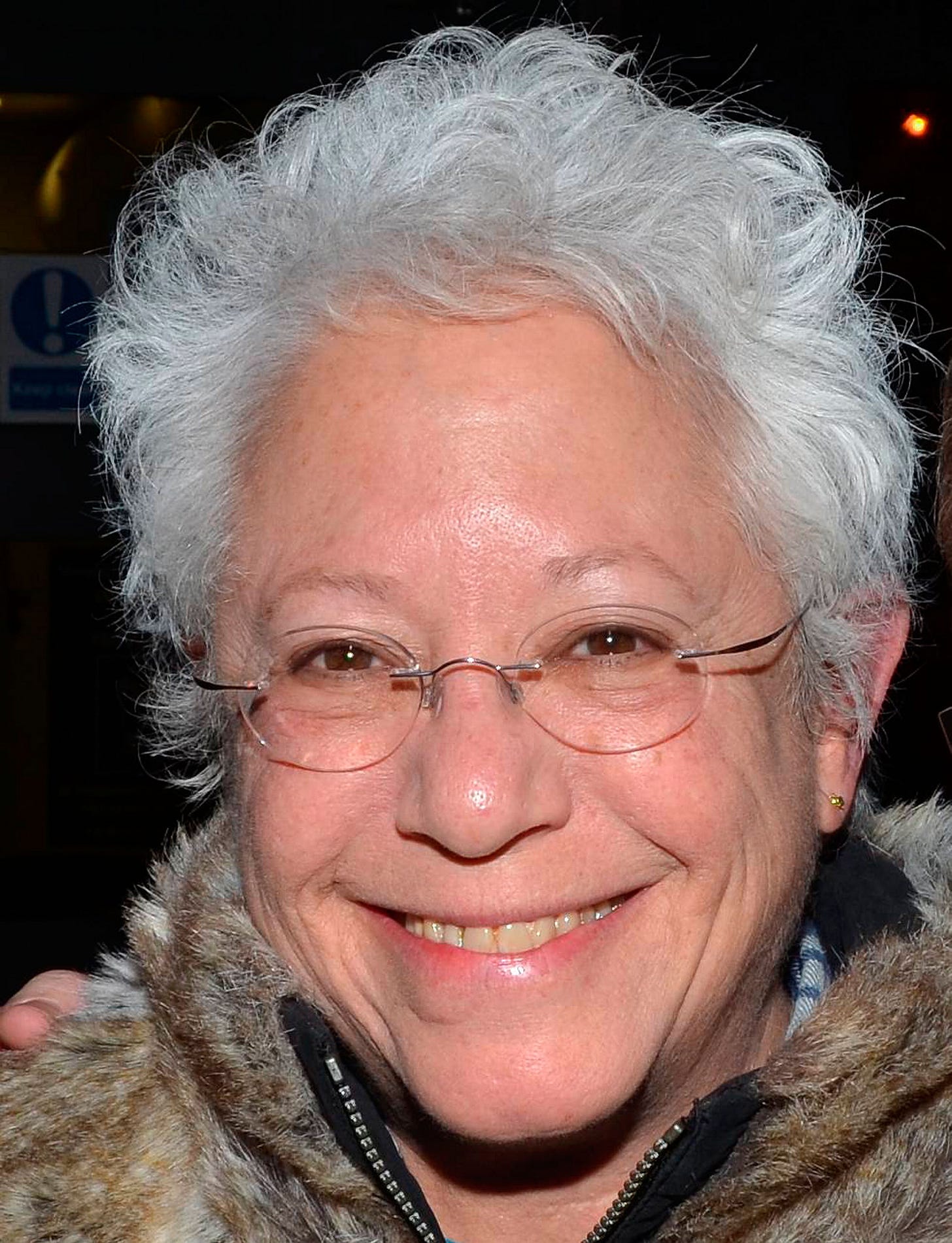

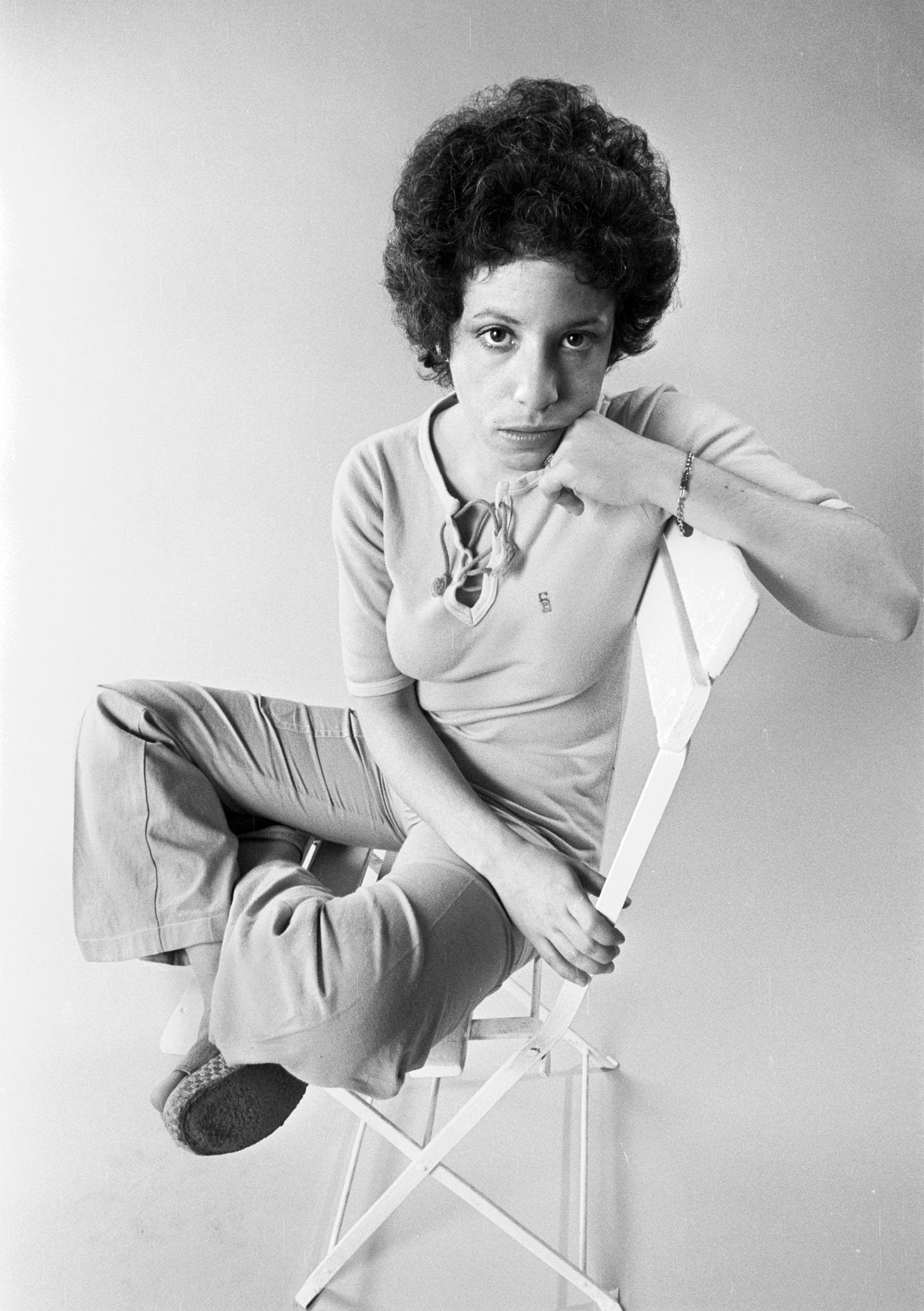

Janis Ian

Relix, June 2006

I don’t remember who it was, but a few days after I had relocated from New York to Nashville as editor of Musician in its new Music Row headquarters, someone set me up for a dinner with Janis Ian. My sense is that this person suggested we’d get along because I was this sophisticated big-city hotshot and she was not only a New Yorker herself but, in a line I eventually realized was already rather tired in this town, one of the few songwriters here who knew more than three chords.

Being aware of who Janis is, namely a creative force equipped with the ideal mixture of integrity, intelligence and no-longer-raw talent, I said sure. And shortly after that we introduced ourselves at the Koto Japanese restaurant in downtown Nashville for a few enjoyable hours.

Over the next several years I would interview Janis maybe five times, I’m not quite sure. I found her funny and very quick: She spoke with uncommon speed and articulation. She was a sharp observer of broad social developments and the nuances behind what might be said to her in conversation. I know that happened with me, which left me even more impressed with her perceptiveness and the tactful humor with which she drew this to my attention.

All this was evident again when we met at Noshville, at the time a popular deli on Division Street, to talk about her new album and whatever else we came up with. As I often do on these sorts of stories, I opened by asking the artist to expand on what distinguishes their latest project from others they’ve done. Often they answer reflexively, with sometimes less than convincing enthusiasm. Not so with Janis; as always, she put things into greater perspective, with a little irony and self-deprecation added when appropriate.

In particular, I think this conversation reflects those last qualities, as it strayed from her latest album to broader musings on how the music world would soon evolve, for labels as well as consumers. Of course, it’s all come to pass pretty much as she foresaw.

****

As you look through your catalog, what does this new album, Folk Is The New Black, represent to you?

I probably would need some time. But off the top of my head, it’s probably the easiest album I’ve ever made, in terms of things falling together without any hassles. We tried only one song that didn’t work. Everything else worked. We got it done in three days. The artwork came together. The mixing came together. So it was an easy album. That’s reflected in the album. I come from the school of musical quantum physics: I really believe that whatever you’re feeling at the time somehow goes into the grooves. Even in a sad song, you can tell if someone was stressed or unhappy while they were recording. So this album feels right.

These songs do cover a large emotional range. Yet there’s also consistency; it flows from one track to another. It must be a challenge to get that kind of diversity and yet come up with a unified product.

This might be the first time I’ve actually managed to do that [laughs]. My eclecticism has been the bane of my career, because I’m a writer first and writers write what they write. You don’t write while thinking, “I’m a jazz writer” or “I’m a folk writer.” I, at least, just write. So to make all of that hang together in a record is problematic, to get something like “Standing in the Shadows” to sit next to “The Last Train” becomes a problem. A lot of the reason it hangs together is that we did it live and it was the same musicians cutting pretty fast. There wasn’t a lot of time to screw it up by saying, “Let’s make this track different.”

Were you in fact writing before you ever sang in public?

No, I did both. I probably started singing in public with my dad at farm gatherings when I was three. I started performing when I was twelve, when I started writing. I always wrote poetry – stuff that kids did.

You were a reader as well as a writer.

And I was verbal. I process outward. My partner says I never know what I’m thinking until I’ve talked about it, and that’s pretty true. I have to work it out either verbally or in writing, whereas my partner has to work everything out internally before she’ll talk.

The Lure of Music City

How is it that you wound up moving to Nashville?

I came here in ’86, just before all the carpetbaggers, because I wanted to write. I set foot on the tarmac at the old airport and thought, “I’m home.” I had a lot of preconceptions that were wrong. I had no idea what I was walking into, except that I felt at home right away. I still don’t know why, but two years later I moved here lock, stock, and barrel.

You came here initially for a writing date.

Yeah, MCA Publishing sent me down here for two weeks. I was living by the beach in Santa Monica. It was very nice, but I felt a sense of community here among the writers that I hadn’t felt since Greenwich Village in the Sixties. Much as there’s a culture shock for a Northerner moving here, because it is a different country, there was also a sense of coming home.

Everyone here is really polite, compared to New York.

It still has a lot of the small town, although that’s fading as the entire country becomes one big TV Land. But there’s still a small-town ethic here. And it’s still a lot smaller than most cities. When I moved here, Metro Nashville, in a sixty-mile radius, was three hundred thousand. And now it’s well over one point two (million). But you still run into people all the time. I just ran into two people this morning. In that sense, people in the South have always understood that there is no real anonymity. You’re going to meet those same people ten years down the line, so it’s best to keep some of those thoughts to yourself.

A Music Row songwriter here once objected to the stereotype of writing so many songs based on three chords by pointing you out as someone who could write songs based on four or more chords.

[Uproarious laughter.] When I started working here, a lot of the A-list writers, like Don Schlitz and Tom Schuyler, kept coming back to, “Why don’t you move here?” I kept saying, “There’s not really a place for me here.” But they kept saying, “We could really use some writers who aren’t cut in our mold.” I found that interesting because they were so concerned with the health of the writing community. In L.A. and New York people are concerned with their BMI statement. In Nashville, Don said to me, when I started writing here, “I don’t want to see you writing only with the A list. I want to see you writing with the B list and even the C list, because we’ve got to give them a shot at working with the better writers. You can’t always write with people who are as good as you or better; you’ve got to write sometimes with people who need the experience. That had never even occurred to me, although I would think about it as a performer with an opener. I’d never thought about helping the writing community that way.

You came here as an established writer.

Yeah, I was very lucky, because I bypassed a great deal of what people usually go through when they come here and need to prove themselves. I was lucky that Nashville’s writing and production community tend to look at what you’ve done, not what you’re doing.

Yet perhaps you did have to prove yourself, in terms of being able to fit in.

Oh, yeah, I had to prove that I wasn’t some snobby Northeasterner who had decided to come down here and teach everybody how to write. In fact, the week I moved here, I was at the Bluebird, and an L.A. producer came in and said, out loud, “I’m gonna show you how to make records!” And I thought, “Man, you’ve just killed your career in this town.” You know, this is a small town. Word gets out pretty quick. I watched Beth Chapman come to town. She sang her song “Emily” at the Bluebird. Two days later every writer in town knew that she was good. But you step out of line … I find I have to be cautious when I release a new record, that I don’t get full of myself. Nobody will call me on it to my face, but it’ll take me years to live it down if I do.

Things have changed a lot here in the past five or six years.

Yeah. I’m hoping it’ll start swinging back. It changed a lot with “Rhinestone Cowboy” and then it swung back. When sales drop enough that everybody stops chasing radio’s tail, it may change some.

“The problem with having a reputation for being good is that there’s nowhere to go but down.”

How has being here changed you as a writer?

Nashville has changed my writing more than anything since Stella Adler. The problem with having a reputation for being good is that there’s nowhere to go but down. I was writing with Deana Carter. It was one of her first co-writes. She was very sweet but also really nervous. She said, “Oh, God, if this is awful, everybody’s going to say that Deana Carter wrote with Janis Ian and it was just awful; she must be crap.” And I said, “No, everybody will say that Janis Ian wrote with Deana Carter and turned what should have been a good song into a piece of crap.”

Once you’re the older, established writer, I wouldn’t say that people gun for you, because I’ve never felt that. But they look at what you do with a different eye. And they hear it with a different ear. You’re expected to set an example. Nashville also forces you to tighten up. It forces you to get rid of bad metaphors and stupid filler that doesn’t work and to tell the story the way the story should be told. In my first week here I was writing with Tom Schuyler and I came up with some line, and he said, “Man, that’s a great line! That’s a great Janis Ian line! I don’t know what the hell it means and no one else will – but it’s a really good line!” That was a slap in the face in the best sense.

From Excess to Essence

The lyrics on your new album show how what you’re saying has integrated into your natural style of writing. Looking at “Jackie Skates,” for instance, I see that the writing is very streamlined …

I love that lyric.

It’s bare, which is appropriate to that story, and yet elegant and eloquent.

You don’t waste time here. You’ve got two and a half minutes, so there’s no time to waste. Since I moved here and tightened up, I find that I’m usually done by the second verse and I’m stuck with, “Well, where do I take it from here?” You try and say everything in the shortest possible space. I don’t know about the elegance; maybe that’s elevated language.

I don’t mean elegance in a rococo sense. It’s like this coffee cup is elegant, in its streamlined simplicity …

… as opposed to Lucite.

When did you first sense that this album was approaching on the horizon?

I wish it were that simple [laughs]. Philip, my co-manager, and I started talking about this album in the spring of 2004. I made a list of everything. This was an unusual album for me because I don’t normally get that codified, but I knew I wanted to make a folk album. I knew I wanted to make a complete change of engineer, of studio. And I also knew that even though the previous two albums had been released through license deals, this was the first one where we were going to be fifty-fifty partners with everybody, which placed a different onus on me because I felt that I owed it to my affiliates to at least make something they could advertise and sell. I had no thought of making something that’s going to sell a hundred thousand units but at least something that would make them back their money and a little besides.

So we blocked out time last year in January and February and, I think, May and June to write. That was new also, because I’d never sat down and said, “Okay, now I’m going to write an album.” Billy Joel does that, apparently, all the time, but I never have. I think that worked in part because I was on the road through all of 2004, so all this stuff, these little scraps of ideas, had built up. Then when I started going through the songs in January, I had spent 2004 literally listening to folk music. Every night, when I’d go to be on the road, I’d turn on the computer and have Baez or Paxton or Dylan on – someone who’d influenced me as a kid – because I wanted to make sure that my album was coming from that spirit. I really believe in “garbage in/garbage out.” Artists, by their nature, take everything in. And then, depending on what you allow yourself to be exposed to, everything comes out.

Then I was kind of surprised when I started writing it. Some of the songs, like “Danger Danger” or “The Great Divide,” had been around in a different form for a while but had never come together. “Jackie Skates,” though, was a complete surprise. I was just sitting there, fiddling with that tuning. I’d had that first line for a couple of years, but where that song went really surprised me.

Was it based on a real incident?

It was, sort of. A friend of mine, Stan Goldstein, was killed by a truck back in the Eighties. His girlfriend’s only concern was that her new pants had been in the back and did they get them out? Some of them, like “The Drowning Man,” came out of nowhere. And some, like “The Last Train” … I wrote it, wasn’t happy with it, wrote it, wasn’t happy with it, and finally did the last rewrite the morning that we cut it.

You obviously made a conscious decision to write the songs for the new album on your own.

Very much so.

These suggest a movement back toward purity of conception and intention. I liked God and the FBI …

… but that pretty much maxed it out. We went as far as we could go and that was the end of that. The only logical thing was to go the other way. We played around with the idea of just doing the voice and guitar, but I decided that since I’d spend the next year doing that on the stage, it would bore me to death. Then the opportunity to work with Victor Krauss came up and that was a no-brainer.

What made this combination of musicians ideal for this record?

They listen. That’s pretty much it. They were excited. Working with someone who’s excited over the songs as a musician is different from working with someone who’s just excited to have a session and earn a living. I thought that Victor’s sensibility as a bass player, because I sing off the bass, would suit. They were enthusiastic. We actually rehearsed for two or three days. They both came in, having charted every single song, and there were twenty-five songs to start with. They both came in with ideas for parts. Neither was worried about speaking up or arguing. All of that is important because it’s too easy for somebody … I don’t mean to brag on myself, but it’s too easy for somebody with my reputation as a songwriter to watch that reputation intimidate people into silence. That’s really dangerous. But I knew [percussionist Jim] Brock wouldn’t be silent; I’ve worked with him for years. And I hoped that he and Victor would mesh, which they did.

Punch Lines

Talk about the challenge of doing humorous lyrics, as you did with the autobiographical song.

How do you mean “challenge”?

Some songs are sensitive, along the lines of “The Drowning Man” or “Home is the Heart,” where the intimacy of the lyric might make it more accessible to you as an interpreter of personal lyrics. But where you’re doing a song with punch lines, is it a different process to find the right delivery?

I never thought about that. No, I don’t think so. “My Autobiography” grew from Philip and me trying to find a book agent for my autobiography. I was sitting one night, alone at the house, thinking, “Oh, my God, how am I going to explain this to my friends?” I started with the idea that it was funny. I mean, I don’t write funny very often, and when I do it’s usually clever/funny. But I’ve never even thought about whether it would be difficult to sing. I mean, I’m the writer, so I put things where they suit me.

The hard thing is that nobody has a song that’s funny with just one punch line. That gets old very quickly. It’s just like watching a standup comic: It’s got to top itself, top itself, top itself … That song almost does. The last verse should have been a little bit funnier, but I was tired and I couldn’t think of anything. But you need to break things up.

This was a three-day recording session. What do you do to get your recording space comfortable?

I do very little. We did it at Master Link, which is an old studio, so (Jim) Brock would say there’s already a good vibe in there. It’s a decent-sized room, very crowded and cluttered. We set Brock’s drums up right in front of the control room window, facing out. We set me up at the opposite end of the room. And we set Victor up at a triangle. We put up some baffles. We built me a riser so I could see over the baffles. The main thing for me, in setting up the studio, is, “Can everybody see everybody’s face? Can everybody see everybody’s hands?” And that was it.

On some of them, like “Life Is Never Wrong,” where Victor plays bass and National steel, he just moved to a chair opposite me. I just put my guitar down and sang on “Crocodile Song.” I’ve seen people bring their rugs and candles and photographs into the studio. That’s all fine. Maybe I’m too compartmentalized, but I survive being a writer, being a performer, being a recording artist, being this and that, to be really clear that what I’m doing right now is what I’m doing right now. I mean, I’m doing press right now; I don’t expect to be at home, listening to music or being creative in terms of being a songwriter. When I’m recording I expect to be recording and give one hundred percent of my attention to that. All that other stuff becomes a distraction.

Changing Times

How do you feel about music being written and distributed these days?

It’s an interesting time. I don’t think anybody thought about that. Who would have thought that this would happen? You couldn’t have conceived of it. I was reading science fiction and I could conceive of a computer. I worked on that big one at Columbia for a year. But there was no way you could have conceived of the amount of different avenues beyond radio. That’s part of what the music industry still struggles with. People were very slow to catch up. I was lucky that I knew a bunch of geeks, so I was online early, I had a website early and I was into digital music early. But that was just luck. The music industry itself is in the unfortunate position of having gotten bigger and smaller at the same time, so you’ve got CBS/BMG/however many thousands …

It’s hard to keep track.

… which is a bigger company but smaller in terms of the latitude each company has because they’re all tied to this huge octopus. It’s difficult for something that monolithic to change or to accept change. And with people my age running these things, it’s hard to change. My partner Pat (Snyder) said to me, after BMG, “Why are you even looking for another major label?” It took me a good year, even though it may be an intellectual decision to stop, to emotionally catch up with “I don’t need a major label” because all my life, for twenty-odd albums, I’ve been with a major label. That’s just how things are. So if it took me a year to wrap my head around it – and I’m pretty smart and flexible – how long is it going to take at Sony?

The key is the elimination of middlemen and the opening of multiple channels of access to music.

I don’t know that you’ll eliminate middlemen. I don’t foresee it in the near future. But then again, I’ve been wrong before.

The artist’s cut, though, will be less eviscerated …

[Laughs.] That’s a good way to put it.

… because you’re not supporting the salaries of publicists and marketing people …

But it’s a tradeoff because you end up supporting a whole other infrastructure. In my little world, I’m co-paying for the publicists. I’m co-paying for everything. You do make more money in the end if you’re careful and it all works out, but you never get the hundred thousand dollar advance. When I was at CBS and I got nominated for a Grammy, I was at a gig the night before and they sent a private plane to pick me up and make sure I got the awards. You don’t get that stuff. On the other hand, you also rarely get treated like a piece of meat on a hook. At my age, that’s a nice thing. If I was eighteen I’d still be looking at going to a major. That may change in a day, but at this point you can’t have a thriving international career without the help of what a major can put in place for you: distribution, advertising, and all of that.

But aren’t the majors more reluctant than ever to invest over the long term on a promising artist?

I don’t know. A lot of acts failed in the Sixties. There were twenty-two record companies too, which is a whole different thing. The bottom line is that for a major record company to get an eighteen-year-old newbie that they can use for twenty years, that makes a lot more sense than somebody who’s fifty-four and probably looking at not going on the road so much. …

It’s like the different styles of management: Some managers really don’t want their acts to know what’s going on, because they may start asking questions. And once they start asking questions, they might figure out that they can pretty much do this on their own without giving away fifteen or twenty percent. Some managers are a little smarter and prefer an educated artist. But the majors are struggling with, “How do I keep these absurdly inflated profits that started with Michael Jackson and turn into U.S. Steel and never run any risks and also keep the public perception that I’m a good guy?”

“If Goddard Lieberson or Bill Paley were still young and running things, they’d take one look at the RIAA problem, hire a good publicist, and get out of town.”

One of the big issues right now is that they’ve totally blown that perception. If Goddard Lieberson or Bill Paley were still young and running things, they’d take one look at the RIAA problem, hire a good publicist, and get out of town. Instead, these people are running around like chickens with their heads cut off. And let’s remember that within the companies themselves there’s this division. Sony’s hardware people pushed computers with recordable discs. Then when you came to the software, which is their artists, the whole record division suddenly woke up and went, “No, you can’t do that.” I mean, I’ve been on board meetings within the company itself where they’re all screaming at each other. They hate one another. Yet they’re tied at the hip to their opposite. So you’ve got all that internal dissent going on. Then you add to that the economy and the political climate, and you add that they’re so big that they can’t move without tremors affecting everything, and it’s a big, fucking mess.

Artists are going to have to become more capable of survival through their own ingenuity.

And they’ll have to become more proactive. In that sense, it’s back to the Sixties. No folk singer expected to get a major campaign or major money. We all figured that if we were lucky we’d get back to the clubs where we started and build a bigger audience and then finally, with a big enough audience, we might get a record contract and sell a few albums.

From the consumer point of view, though, you or Judy Collins or someone else would put out an album and it would appear that you had it made.

That was my perspective too, until I started doing it. You think that if you get a contract, that’s great, you’re in. But in any business, life is “if I could just.” There’s always an “if I could just.”

The basic reason for these problems is technological. In those days you couldn’t get hold of music unless you bought a vinyl disc.

And you couldn’t make that disc unless you had a budget.

And now all you have to do is get a copy of the master of the next Elvis Costello album, put it online, and there you go.

I’ll take that a step further. You don’t need a record company to make records anymore. That’s a huge shift in the paradigm. Anybody with a computer and Garage Band can make an album. And a lot of times it’ll sound better than what the majors are funding.

“We’re not selling CDs. We’re selling dreams. And if we don’t sell dreams, we have nothing to put on a CD.”

That’s one of the casualties in all of these changes. There are producers who do make a difference, but their contribution will be devalued over time as low-budget recording changes the perception of what production is.

That’s very possible. But it has to be a flexible business. At the end of the day, art survives. I once told a group out at Belmont (University), “Don’t forget, we’re not selling CDs. We’re selling dreams. And if we don’t sell dreams, we have nothing to put on a CD.” Record companies forget that. I think that we as artists tend to forget that too, as we get caught up in the day-to-day business nonsense.

That’s the other downside of where things are going now: Artists have become, in many respects, much more proactive. Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings have their record company. Ani [DiFranco] has her record company. I’ve got my record company. But that also means that you spend a proportion of your time doing things that are not in the arts. I hesitate to say “not creative” because I find something like negotiating a contract creative. But for most of us, there’s less and less time to do what we care about. It’s hard to set up an affordable infrastructure that will buy you that time. But you have to. There’s no way around it, if you want to survive. But it’s hard because it forces you to be a grownup, and no artist wants to be a grownup. You only want to be a grownup when you’re ten.

Can you project ahead and imagine where the public and its expectation of getting access to music will lead us five years from now?

I am so totally clueless. You learn, as you start getting older, that things can change on a dime. You never really believe it when you’re a kid, unless you suffer some huge, sudden tragedy or grow up in the middle of a war. But once you hit your forties and fifties, and people start dying, and events start changing, you become all too aware of how quickly things can mutate. So I have no idea. (Apple co-founder Steve) Wozniak is probably the guy to ask.

What’s he doing these days?

He’s teaching two or three days a week. He goes in and gives computer classes to kids. He’s busy sending out bad jokes. Guys like that have their pulse on what’s going on in technology. I don’t; I’m happy if my cell phone works.

I would hope that the music industry calms down a little. This is not brain surgery. Nobody’s dying here. We have such high financial expectations. And, man, I’ve been all over the world, and I know that we live very, very well. The poorest people here, if they can figure out the system, can live, as opposed to in Dubai or Djakarta or any of those places. Americans – and I include myself – are incredibly spoiled. There’s always a reckoning. I reminded somebody from New Zealand the other day that we’re only 230 years old, which is not very old in the scheme of nations. After 230 years, to be the biggest and the richest, well, yay, but there’s a parallel to the music industry: It’s so isolated, it’s so used to having it easy. And there’s got to be a reckoning.

####