Ever since that morning in 1966, when I turned on the TV in our new home near Washington, DC, and saw Bruno Sammartino wreak righteous vengeance on some evil-looking troublemaker, professional wrestling has fascinated me. When it was the exclusive realm of cigar-chomping, beer-swilling, blue-collar guys, I watched the matches clandestinely, as others my age eyed Playboy or puffed on their dad’s Marlboro. When it became trendy among college kids as an ironic joke, I crept out of the shadows to read Pro Wrestling Illustrated in natural daylight rather than in my bedroom, curtains drawn and door locked.

Eventually I found my niche in music journalism, which for more than forty years paid both rent and mortgage. But my interest in “sports entertainment” sustained and even intensified. No other dad I know took his family to a local theater to watch Wrestlemania II, where Hulk Hogan obliterated the massive King Kong Bundy. Decades later, I arranged a backstage interview with WWE superstar Kurt Angle while ostensibly covering the CMA Music Festival in Nashville, to talk about the differences between competing in the Olympics and on WWE’s Monday Night Raw. And when I encountered Brooke Hogan, Hulk’s Amazonian daughter, at a rooftop party in Nashville, I “marked out” (in the vernacular, got quite excited).

None of these brief thrills compared to when I persuaded the weekly Nashville Scene to let me do a cover story on an upstart wrestling organization, Total Nonstop Action. In those days, TNA staged its matches exclusively at the Nashville Fairgrounds, which were taped and then syndicated nationwide. Though tiny compared to the industry leviathan, World Wrestling Entertainment, TNA bristled with outstanding new and veteran talent, in and out of the ring.

Before pitching to the Scene, I walked into TNA offices at the Cummins Station complex and just stood there until someone came out and asked why I was there. In a few minutes I persuaded them to set up interviews and backstage access at both rehearsals and the actual matches. A few weeks later, I drove to the Fairgrounds, feeling like how I imagine swooning fans feel when they meet Taylor Swift. I did formal sit-down interviews with a number of wrestlers, most notably with one of the industry’s all-time icons, the “American Dream” Dusty Rhodes. I watched as pre-match choreography was worked out between soon-to-be opponents. Best of all, I grilled announcer Mike Tenay, known as the Professor for his command of wrestling history … and stumped him with a trivia question! (Me: “What were Bruno Sammartino’s legitimate middle names?” Him: a baffled silence. Me, triumphantly: “Bruno Leopoldo Francesco Sammartino!” Him, grumbling: “Well, he was an East Coast guy. I was more into Western territories …”)

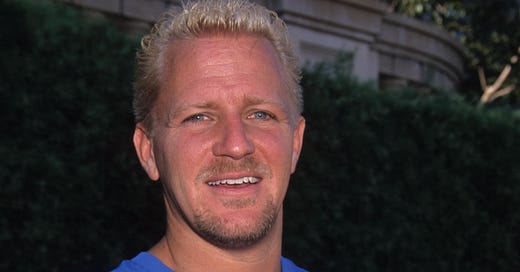

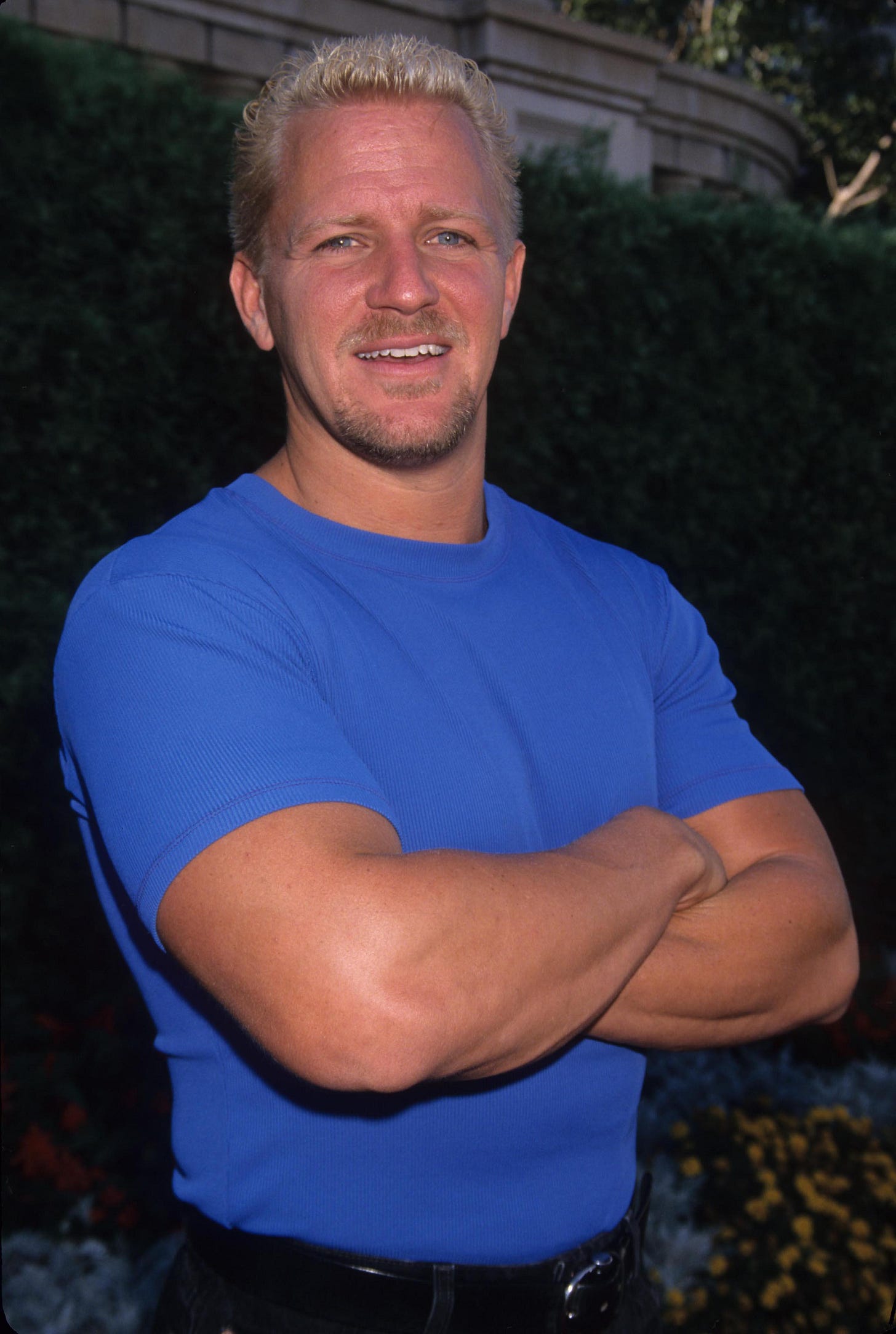

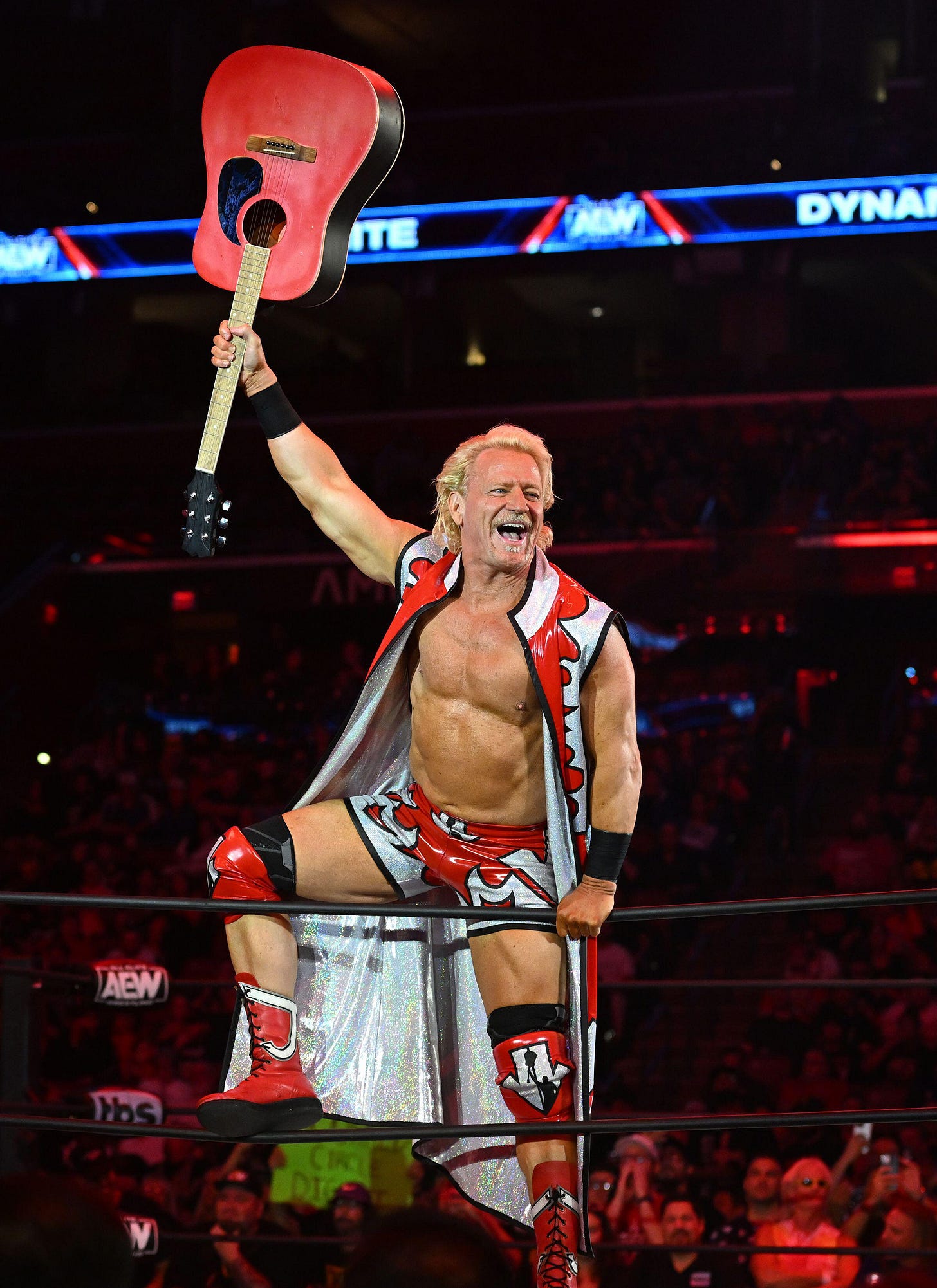

Sadly, when scouring for transcriptions of my interviews, I could find only one, with Jeff Jarrett, a well-known veteran and son of promoter Jerry Jarrett, who had built the Tennessee territories into a formidable presence. Along with journalist Bob Ryder, the Jarretts came up with the idea for TNA while on a fishing trip: With the collapse of World Class Wrestling, billionaire Ted Turner’s bungled experiment in the wrestling biz, the Jarretts and Ryder agreed that an opportunity had opened for them to launch their own alternative to WWE. They weren’t wrong; In fact, under the name Impact Wrestling, their organization continues to this day – and just weeks ago it decided to revive the TNA brand. Though Ryder and Jerry Jarrett have passed, Jeff remains active, with yet another WWE rival, All Elite Wrestling. Even so, Impact/TNA is part of his long legacy in the business.

****

Have you ever wanted to do anything else other than be a wrestler?

I guess I had some illusions. I played basketball one year in college and I wanted to pursue that as far as it would take me. But on a serious business view of having a lifelong career, this is without a doubt something I always imagined. And once I got old enough, I took it beyond my boyhood imagination and went straight into it. This is really what I want to do. I want to perform. I want to be a part of this business. As a teenager I did everything from working concession stands to selling pictures to setting up the ring and then move into refereeing. I’ve done a little bit of everything in this business.

You refereed for the first time in that very building where TNA does its weekly show.

Correct.

What’s it like to come back to where you began as the next step in your career?

I never dreamed I’d be doing a weekly pay-per-view that would be seen in Perth, Australia, out of that building [laughs]. I can remember sitting in my office, in that box office where the tickets are sold today; there was another ticket booth in that building at the time. I remember sitting there and looking up at my grandmother selling tickets twenty years ago. It's still sentimental or odd or even at times emotional when me and my dad are at that building every Wednesday and to know that years ago wrestling was performed in that building on Wednesday nights. It later moved to Saturday nights. So there’s a lot of history with the Jarretts in that building.

What was it like growing up in the business? Was it kind of an adventurous life, like joining a circus?

There’s two sides to it. My dad was not around a lot when I was growing up because, especially in those days, you spent a lot of time in a car. They had a wrestling territory that stretched from about ninety miles north of Louisville, Kentucky, to maybe a hundred miles west and south of Memphis, Tennessee. It went all the way down to Birmingham, Alabama. It didn’t go very east but it stretched a long way north and south. So Dad was gone six or seven nights a week. He was gone an awful lot; you can imagine, as a kid, I’d get home from school and he’s not there. So I missed a lot of that.

But as you get older and you get to go on weekend trips, those are the times you remember it very fondly. Most of my other buddies were hanging out at the local swimming pool or playing basketball in the gym during summers. I would do that during some summers too but a lot of times I was on the road with my dad. We’d go to a different town every night. I was behind the scenes and got to see matches. I was living my dream at the time.

Fishing for Ideas

What you’re doing with TNA seems like a return to the intimacy that wrestling saw when local markets dominated wrestling, now with the unlimited access to today’s digital media and national television.

The old concept is out of bounds because of what you’re talking about, that we have the intimacy of a regional or local territory mixed with a worldwide fan base. Also, in the past ten years you’ve had Raw or Smackdown or Nitro or Thunder on a Monday and Wednesday or Thursday night. It would drive the audience to your monthly pay-per-view. In the territory days, you had your Saturday morning time slot, which was a promotional tool, if you will, to drive people down to wherever the live event is.

Ours is that hybrid form. I guess you could say we’re a Raw and a pay-per-view rolled up into one. We are a weekly pay-per-view series. If you want to see TNA, you tune in on Wednesday nights. We don’t have the traditional promotional tools, where you drive them to the pay-per-view or the live event. We hook you in every week and truly give you two hours of a very entertaining program. The name is sometimes overlooked, but Total Nonstop Action is really what we’re about. We realize that we’re in competition with whatever else is on television that night, so we have to serve our market well.

What kind of a business plan did you, your dad and Bob Ryder come up with on that fishing trip?

The question was asked on that fishing trip: If you put wrestling on a pie chart, you have seven or eight income streams. You have pay-per-views, you have merchandise, you have licensee products, you have publications. Well, on the model that WWF and WCW were going under, pay-per-view was the biggest stream. So he made the statement to my dad: “Why don’t you want to be in the business?” He said, “It’s too risky of a business.” But the pay-per-view business is not risky, because that’s the thing that makes money. Bob said, “Well, why don’t we just do pay-per-view?” One thing led to another.

By broadcasting from the Fairgrounds and not doing house shows all over the country, you avoid another big expense.

That was the other thing, as far as being risk versus reward. The house shows are a big risk. WWE numbers show that even in the best of times it’s a huge cash cow. If your TV numbers aren’t as good as they could be, you’re not gonna get as much money through advertising. Our original business plan was actually not to be at the Fairgrounds every Wednesday night. We were going to be a traveling road show, if you will. Well, two years ago in May, the house-show arena business was at a certain level. if you look at it now, it’s down by at least half, I would say.

Did you ever consider moving your headquarters to more of a media center than Nashville?

This is definitely the home office. This is where I’m from. But everything evolved and changed since Day One. One thing that’s made us what we are today is that we have been able to adapt. We’ve had everything thrown at us, from legal situations from guys who we found out weren’t actually on our team to situations that were beyond our control going south on us to talent situations. [Note: Jarrett’s mention of “legal situations” cued me to do some quick research before my interview with Ryder. Moral: It pays to listen alertly to what the subject is saying. The results of this inadvertent tip can be seen in the final published article, at https://www.nashvillescene.com/news/battle-royale/article_9ba444e5-8a7c-5ea8-b2a5-bad7796f018a.html]

Does this connect with the post-911 mentality, as with so many things in the entertainment world?

I think there’s a nesting situation going on throughout the United States. With the war going on in Iraq right now, it’s getting even worse.

David vs. Goliath

So you avoid expenses that really are unnecessary in this day and age. But then you have the challenge of breaking into an industry that is dominated by another company. How did you address that situation — and also, did it suggest certain opportunities to you?

I definitely think so. If you just look at the short history of the wrestling business since it became national, when the territories went almost instantaneously out of business even though they didn’t know it yet, when USA picked up WWF and Turner had WCW, when their competitive juices were flowing, that’s when the business flourished. When one got too far up front and the other one dropped back, it wasn’t good for either one. Overall, all numbers went down. In ’96, ’97 and ’98, during the Monday Night Wars, that’s what was going on. Business was good for both sides. So I think there’s a great opportunity for us and we’re starting to capitalize on that as an alternative.

To what extent do you base what you do on offering that alternative to what WWE does? Or is it about not paying attention to that and looking at your assets to define what you do?

We’re both wrestling programs. They tend more to be … I don’t want to call them “hokey” because they’ll go through phases where they’re not hokey, but they’re more entertainment-based. There’s a real fine line between it being wrestling and it being entertainment. “Sports entertainment” is the term that McMahon coined to get out of paying taxes up in the Northeast. Sports entertainment and wrestling are really very much the same thing but there’s that fine line when you go too far into sports entertainment where there’s a big difference. And we are more wrestling-based.

“Good, realistic storylines have always been what’s tried and true in this business.”

It sounds as though growing up in the business gives you an old-school perspective on what wrestling is or ought to be.

I don’t really think so. Maybe I’m the inside looking out, but the pendulum has swung far towards entertainment over the last four, five or six years. In the late Eighties we went through what I would call the cartoon era of characters. Then the business nosedived and they went through a more reality-based attitude era. That caught the public's attention. But now there are no characters being evolved. You have to keep up with the times. On ESPN, you’ve got the X-Games and extreme sports. We have a division on TNA that fits that mold; we’ve got our X-Division.

Good, realistic storylines have always been what’s tried and true in this business. Dating back to the Fifties, Sixties and Seventies, if you have what in the business you call a hot angle, a good story that really touches a nerve and that the people can believe in, that’s gonna make you money, get you eyeballs and get asses in the seat, week after week.

Keep It Real

How is a good storyline created?

Whatever is real, that’s what works best. I know that sounds hokey coming from the wrestling business [laughs], but right now one of our main storylines is just what we’ve been sitting here and talking about: sports entertainment Xtreme, S-E-X, which is pushing the envelope more. Sex, vulgarity, violence, brutality, versus wrestling. Our wrestling is tied in with the NWA. The NWA, for real, is the oldest governing body, storyline or non-storyline, of wrestling. The NWA world heavyweight champion has a title lineage that dates way back. Anybody you talk to who has any kind of knowledge of wrestling — they don’t even have to be a fan — will have one of two opinions. They watch Shock TV or that crap that they’ve been putting out, or they watch wrestling. So the talk on the street is: Which way is wrestling gonna evolve? Is it gonna go more toward in-ring product? How much more can you push the envelope toward more of a shock basis? I don’t think you can really shock the world anymore when we’ve seen 911, when we’ve seen to 747s going into the Towers. When you’re watching war on television for real, that shock TV is passé. Reality TV is what’s hot right now. So I think storylines have to come from a reality-based standpoint.

Over the past five years, Steve Austin shot to stardom with Austin versus McMahon. But really, that storyline started in 1986, with Vince McMahon standing there with a microphone and everybody was like, “Who is this goofy-looking character in that goofy suit?” Then it became known that he was the owner of the company. Then there was the steroid scandal, which put a little tan on the owner’s image. Then he was the owner of the company with a huge real-life situation where, in the fan’s eyes, he screwed the most faithful employee he’d ever had. Bret Hart came to WWF as a kid in ’88 and had been on the road over 300 days a year for years and years and years. He gave his life to Vince McMahon, and Vince screwed Bret, so the story goes. Is it real or is it not? The real story was, Bret was used in that storyline and Austin got the cherry on the top. He was the employee that got to kick the boss’s ass.

There’s a similar storyline going on here in TNA between Mike Tenay and Vince Russo. I spoke with Mike today and he had less than complimentary things to say about Vince. Now, I’m not asking if that’s true or not. But if it were true, could that be some source of heat for the show?

I can tell you: It is true. Everybody in this room has an opinion about Vince Russo on a personal level. But move the personal level aside: Everybody’s got differing opinions on how he thinks the wrestling business should evolve. Russo is just so far to one side. Mike Tenay is a wrestling historian. He’s got great respect for the business. Russo, for real, has zero respect. He’ll tell you he doesn’t! He doesn’t have respect for the past because he don’t know the past. It’s almost an ignorance point of view. Some guys say Vince doesn’t know what it’s like to be in the ring; you’re right, he doesn’t.

“There’s not one person out there, including myself, who’s totally smart to the business.”

What are the pluses and minuses of putting a wrestling organization in the post-kayfabe era? [Note: “Kayfabe” refers to the imperative of making fans believe that wrestling matches and feuds are “real,” not scripted. However, it’s understood these days that pro wrestling is predetermined, exactly as actors play their roles onscreen.]

You’re talking specifically about smart fans? There’s not one person out there, including myself, who’s totally smart to the business. Everybody can be fooled. Just like there’s not a horse that can’t be rode or a cowboy that can’t be drove, it’s the same with the business: Everybody can be worked. It’s no different from a movie. They can come up with every new sci-fi thriller in the world, with every special effect. But at the end of the day, the great movies are the ones that have real raw, human emotions.

During the Eighties, during the rock-’n’-wrestling fad made it hip for college kids to start watching, part of the attraction was kind of ironic. That element has kind of gone away. What you guys are doing is to draw a smart but sincere and loyal audience. They’re on your side.

Well, during the Eighties and then during the late Nineties, wrestling became a fad. They say that’s the cycle of the business. But there are always wrestling fans out there. There always will be. We appeal to a large demographic. How in the world can the lower-class people afford to go to a Predators game? Or even take their family to a movie and go out to dinner? That’s two hundred bucks! If it’s a family of four, you’re going easily over a hundred bucks. Wrestling tickets were going for five bucks back in those days; a football game would have been twenty-five.

Building the Team

How did you recruit the people you needed to launch TNA?

The wrestlers or the staff?

Let’s talk about the staff first.

We all knew each other. WCW went out of business in May 2001. In October of 2001, there was a guy who was going to tour internationally. I worked on the show; Jerry did too. Bob did the travel for the guy. We were all friends, long before TNA was ever considered. We all did different jobs for WCW. We all knew that we could do more than what we were doing in WCW. Jeremy was on the creative writing and Internet. Bob did Internet but his own personal business was the travel department. I wrestled but had been involved in all aspects of territorial promoting. Ron Harris was a road manager for Sawyer Brown and also wrestled. I guess that was the original four.

“Everybody is fighting for their spot in a healthy kind of way.”

How big is the support staff now?

We’ve probably got twelve now. But we also have everybody in the truck. A lot of those guys, the producer and director of the show, had done the majority of Nitros for WCW and a lot of pay-per-views. Everybody we brought to the table had worked together on some level.

On the talent side …

That’s where it really differs. Whenever you assemble a group of people, if you have everybody on the same level and you have a good mix of veterans, prime-time players and young, upcoming stars, it’s healthy because everybody is fighting for their spot in a healthy kind of way. That’s what we tried to create here. We’ve got young guys who are putting out an unbelievable effort. We’re gonna see them develop into the stars of tomorrow.

You’ve even invited fans who want to get into wrestling to send you audition tapes, like artists auditioning for record labels. How has that been going

You’d be amazed. We’ve had people drive ten, twelve, fourteen hours down here for a shot to get onto our stage. Amazing Red (a.k.a. Jonathan Figueroa) came in on a Greyhound bus from upstate New York.

How does TNA differ from ECW, which also operates out of a small home arena and is looking for cable exposure?

I think their name connotes what they’re about: Extreme Championship Wrestling. They went down that avenue of being extreme on everything. I’ve got a huge philosophical difference with that, because if you don’t have any white, you don’t have any black. If you don’t have any good, you don’t have any bad. If everything is extreme, it’s like eating steak seven days a week. You get tired of it. That’s the biggest difference.

The other big difference is, they were approaching it from a traditional point of view. They got on TNN. They wanted to be a traditional wrestling company and push people toward a pay-per-view buy. We’re different in that aspect.

I was at your show in the Nashville Fairgrounds on the night the United States took action against Iraq [i.e., the Gulf War, launched Jan. 16 1991]. Nobody in the room, myself included, knew about that during the matches. I learned about it on the radio afterwards, while heading back home. Were you guys aware in the locker room of what was going on at the time?

I believe it was MSNBC; they started from the time President Bush said, “You’ve got forty-eight hours.” That forty-eight hours was the countdown to the beginning of our show. So we could watch the TV late Monday night and say, “Okay, guys. we’ve got forty-five hours ’til show time.” There was a lot of discussion. There were mixed emotions. We said to ourselves, “We’re gonna learn a lot about the wrestling fans we’re currently drawing out there.”

###