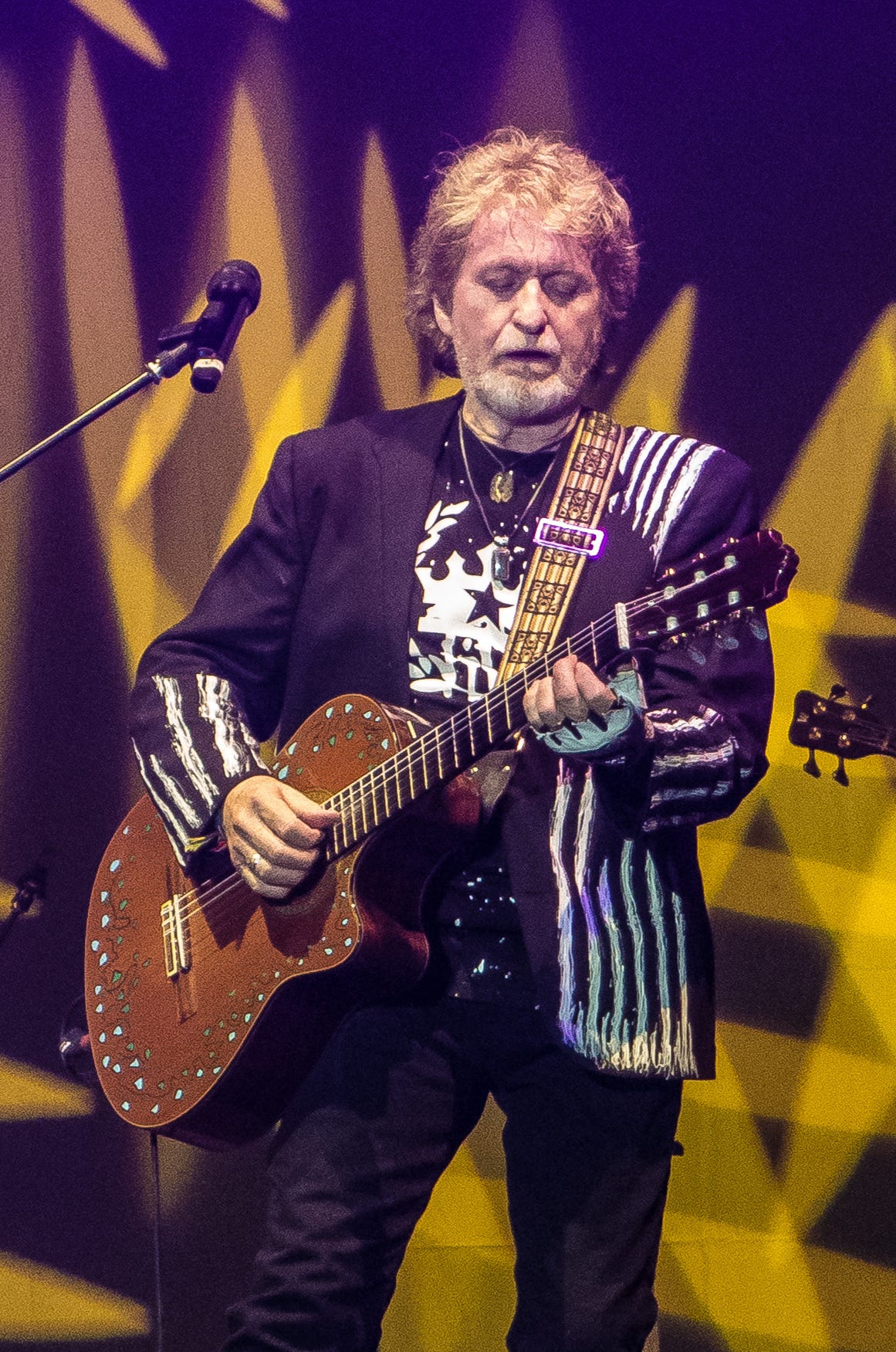

After posting the first part of my interview transcript with Jon Anderson and then looking through the rest of it for this second part, two thoughts began to take shape. One was that, contrary to my original recollection, I’d actually met him long before we had this conversation over the phone. Back in 1982, I drove up to San Francisco to chat with David Sancious for a Keyboard Magazine profile. He was passing through the Bay Area on a Jon Anderson concert tour; my guess is that they were performing that night at the Fillmore, but we had arranged to meet that morning at the motel where he and the rest of the band were staying.

It was strange enough that Anderson, an especially majestic progressive rock icon, had spent the night in this rather pedestrian inn. The glory and dimension of his work with Yes just didn’t fit its vibe. Later, of course, after meeting with artists in even less grandiose settings, the disparities between art and real-world budgeting became less incongruous.

But it was still weird to be sitting in the run-down lobby and suddenly hear Jon Anderson calling my name. He shook my hand, looked me in the eye and spoke like someone who lived to connect with strangers, to find out something about them and share a bit of connection in whatever brief time they might have together.

That same impression permeates our conversation for The Allmusic Zine, which wound, river-like, through a varied landscape of ideas. (Just now, in examining this metaphor, I came across a discussion on yesfans.com about Anderson’s fondness for river references: “Close to the edge, just by a river, seasons will pass you by,” “And you and I reach over the sun for the river,” “Set your heart, sail along the river, look around as you drift downstream,” “This indecision can break me down; let it run to the river,” “Destiny, like a river to the sea, make me believe again.”)

Like a river, Anderson’s curiosity, his proclivity to search and hope for discovery, felt limitless to me. I’ll bet that river still flows, that search continues.

At the end of my first Jon Anderson post, he referred to two difficult moments that Yes had to weather. The first of these involved Tales from Topographic Oceans. We continue here with the second.

****

What was the second piece that triggered some turbulence among band members?

I think it was when we had a big hit record with 90125. We were supposed to make another [album], and I suggested that we make it more in the Yes style. Let’s make some – dare I say? – longer pieces of music, without restriction. If you’ve got a hit song, it'll come out. And of course U was asked to stay out of production for three months. Trevor Horn told me to stay away. It was an incredible disrespect for who I am, what I do, and how I can work with everybody, but there was a lot of power-playing going on in the band, Now, Trevor Horn, Trevor Rabin and Chris Squire all believed they created a hit record for the band, which was “Owner of a Lonely Heart.” I was only the singer. When you think about it, that’s very cruel. But I forgive everybody, and I have high hopes that they would forgive me for my indiscretions. At times I can be a pain in the ass too.

How did you feel, then, as you were laying down the vocal for “Lonely Heart”?

I thought it was just magnificent. I thought the album was perfect. I wrote a lot of the lyrics and a lot of the choruses. I added a good thirty percent of the contents, to give it more “Yessification,” if you like. And it worked. But they said, “We want to do it like we did 90125. You get lost for three months, and we’ll call you.” They just wasted a lot of energy and money, and it frustrated everybody to watch it happen.

At the same time, I went off and made a couple of albums, one with Vangelis [Private Collection, 1983] and one was In the City of Angels. I mean, I’m a musician. What am I gonna do, sit around on the beach and pretend I’m a rock star? During that two-year period of making Big Generator [released in 1987]. I had to keep busy making music. At the end of that time, I realized that my voice was getting smaller and smaller within the sound of the band, so I left to do an album with Rick, Steve and Bill.

That was Anderson-Bruford-Wakeman-Howe.

Right, and that was a breath of fresh air for me, because I was doing what I believed was a good Yes album, without using that name. I didn’t want to get involved with the name Yes. But if you listen to that album and, say, The Ladder [1999] or some songs from Keys to Ascension [1996], you’ll hear that it’s more of that Yes style. That’s not to say there’s anything wrong with the style of Talk [1994] or the style of 90125; that’s the Trevor Horn style, and Open Your Eyes [1997] was Chris and Billy [Sherwood].

The two Trevors may be the two most controversial players in the history of Yes, in terms of either modernizing or compromising the band’s sound.

It’s half and half. They did a lot of great things, and they did things that weren’t right for this kind of a group. Thank God we got back to what the group is, which is The Ladder. After so many years, I’ve gotten to the point that, halfway through recording The Ladder, I could be so thankful that I stuck through all the hard times. But if you look at the whole thirty years of the band, maybe twenty percent of that time was really tough, and the rest was joyous. Even Talk was a fun thing to do, because I was very close to Trevor on that.

So you imagine that you’ll be crossing paths with former members of the band in your upcoming projects? Or will you mainly be recruiting new talent?

It’s very hard to say. There’s always a chance that this can happen. It depends a lot on the success of the new album and whether that will enable a producer to want to put a tour together with Trevor and Rick. And would they want to do it? Would we want it to happen? All of these possibilities are fascinating because when you’re successful, people come knockin’ at your door. And when you’re not, you’ve just got to get on with it.

Ambition & Excess: The Soul of Yes

As the band changed, how did your process as a songwriter change?

I had this fear of being a one-hit wonder – you know, having a hit record, being famous for ten minutes and that’s the end of your career. So I was always reluctant to force myself to write a pop song or a commercial song. I was more into stretching my imagination and working, especially with Steve Howe. Steve brought in more chord structures; you could always get halfway through a song and stop to just let Steve play the acoustic or do something very different, like going into a jazz mode in “Perpetual Change” [from The Yes Album, 1971].

That’s one of the songs we’ve started to play again. It’s an interesting song because of the structure, and the structure comes from many different thought patterns. You get to a certain point and it’s like, “Let’s not go to the chorus. Let’s go into a musical thing. What were you playing before, Chris?” And Chris would be playing [Anderson hums a section of Squire’s bass part from “Perpetual Change”]. “Let’s go there for a while.”

So you’d spend a minute or two doing the music before the chorus came. Already, by then, you’re stretching your imagination. You’re not really considering the length of the music; you’re just waiting until it naturally finishes. That’s where a lot of my listening to classical music comes into play: You start to understand form and shape and good structure. When you study, like, the [Tchaikovsky] 1812 Overture, it’s really the same piece of music played three times. The structures change, but it’s the same themes.

“If you do the music correctly, it’ll last.”

And that’s the approach you took on Close to the Edge, Tales from Topographic Oceans and other large-scale Yes albums.

Yeah, because that was a good place to go. Nobody else was even attempting to go there, so why not? We’ve been able to stand the test of time by doing that, so it’s obviously well-documented that if you do music correctly, it’ll last.

The sound of Yes has in fact survived for decades, though it has also gone through some major steps.

It goes through changes when you bring in different people, especially in the Eighties, when we went with Trevor Horn’s production. He was doing great stuff with Duck Rock, with Malcolm McLaren and Art of Noise. In a way, he was the next extension of the production we were doing with Eddie Offord on Close to the Edge. Trevor Horn put us into that with 90125.

Do you think that some of the more ambitious Yes projects went a little too far? Were there times when you might have scaled down to a more accessible, riff-based structure?

When you’re given free rein to make music, you shouldn’t be too concerned about what the end product is gonna be. Just doing it is the most important thing. At that time, we were sort of bombarded by the record company and our management to not do this kind of music. But that only made us more powerful, because at that time I was learning about Stockhausen. I was learning about Stravinsky. At the time, I Was very interested in electronic music and pushing the envelope totally into free-form jazz, fusion and classic rock. The guys in the band thought I had really lost my sense of reason, but I was saying that we shouldn’t be entrapped in the business because once you’re entrapped, then the business rules. By then, punk had happened. Accountants were controlling the record companies. The whole idea of avant-garde music became a backlash in a way. It was like, “You’re dinosaurs. You shouldn’t be making this kind of music. Who do you think you are? That’s when you have to stand by your dreams.

Of course, in those days audiences were more open to innovation than they are now.

Yes, but it’s so bizarre, because we just finished South America, and we were playing long pieces of music, and they’re singing along to every damn song. They’re singing “Awaken” [from Going For the One, 1977], they’re listening to older music, they’re cheering. So there still is an audience for in-depth music – I wouldn’t call it “evolved” so much. If you want to listen to grunge, hey, just go around the corner. It’s all over the place. You can go to your R&B show or your jazz show or your progressive rock show. You have choices, as you always have.

And in fact there are plenty of opportunities in your music to latch onto four-beat grooves.

Oh, yeah! I mean, “Roundabourt” [from Fragile, 1972] is just three or four chords. “Owner of a Lonely Heart” is the same chords as “La Bamba” or “Twist and Shout.” …

Solo Flights

How is cutting a Yes album different from doing your own solo project?

When we’re working on something like The Ladder or Close to the Edge, there can be so much excitement in a day’s work. It’s a very professional way of working, when everybody is there on time and making sure they’re working at least four or five hours a day. That is great.

Now, when I’m working on my own or with somebody like Vangelis, it’s very spontaneous. I can get a lot of music done in a very short period of time, because I’m doing really what I want.

I remember that when I was doing “New Language” for The Ladder, Bruce [Fairbairn, producer] turned around and said, “Is this track finished?” I said, “No, I think at the very end, it would be great if me and Steve could do a song.” He said, “Well, what are you gonna do?” I said, “Steve! Get your Portuguese guitar and let’s write a song!” He came in and said, “What are we gonna do?” I said, “Just play me some chords.” He sits in front of the microphone and we write a song. Then I said to Bruce, “That’s the song. Now Steve will go and learn his parts, and I’ll write the lyrics.” That’s the way I worked with Vangelis and with Igor [Khoroshev, keyboardist]: He’s very quick to write a song. But putting it together, piecing the jigsaw parts together, can take a lot of effort and time.

Is there less of an emphasis on structural complexity in your solo or outside projects than with Yes?

I don’t know. I did an album called EarthMotherEarth [1997], and somebody said it sounded like a framework for a Yes album. Some of it was very simple songs, but then there was a very interesting project that I was also working on at the time, which was a concerto for guitar – and then I decided to sing it [laughs]. I had two movements of the guitar concerto in that album. The album as a whole has quite a complex arrangement, but not as complex as working with five or six musicians who want to get their rocks off. Everybody tries to find his little part to play, and it starts sounding very complicated. But really, it’s each person creating his own place. It sounds like every note has been worked out, but that’s not true. I’ll say something like, “Wait a minute, Igor. That’s not working. Can you try it maybe an octave higher? And maybe change the chord structure a bit? Oh, yeah, that’s great.” That’s the way it works: You discuss things.

Some of the keyboardists you’ve worked with outside of Yes, such as Vangelis and Kitaro, seem to specialize in coloristic, textural work, while the typical Yes keyboard player is oriented more toward playing fast, chops-heavy passagework.

Well, that was the idea. I wanted to work with the opposite energy. When I first worked with Vangelis, that was when the band was really getting too technical. At that time, I was very interested in the band doing some free-form jazz/rock. That was around 1976 or ‘77. See, I heard them rehearsing once, and everybody was soloing and making this incredible noise. Honestly, it sounded unbelievable. But when I asked them to do it again, they couldn’t do it. Somebody would say, “Well, what key was I in?” And I said, “There you go. You’ve lost it.” You can’t decide what key anything is in when you’re doing free-form music. That’s where I was going in my head. Or I thought we should do some dance music.

Dance music?!

I’d just been to the Trinidad Carnaval, and I was mesmerized there by the steel bands, with their rhythm and everything. I was still covered in glitter, would you believe? Now, this was just about six months before Saturday Night Fever and the Bee Gees, just before disco,

You weren’t talking about Yes doing a disco album, were you?

No! Just something that everybody could dance to. But they said, “Jon, could you just put that bottle of rum down?” I’d just gotten off the plane in this incredible high stage of dancing.

Anyway, when I started working with Vangelis, it was the opposite end of the musical scale. I was doing spontaneous music with someone who could create these incredible landscapes of sound. I was very into Stockhausen and Wendy Carlos and Terry Riley. I used to love all that music. Working with Vangelis was the key to moving away from where Yes was going, which was too technical and, I thought at that time, too unmusical. He became my mentor, because at that time I had hardly ever played keyboards. At that same time I met Vangelis, I met a guy called Ilhan Mimaroğlu, who created some remarkable electronic music in the Sixties. And today, some of the twenty-year-old keyboard musicians in London are doing remarkable things with drum ‘n’ bass or street dance music.

These musicians are putting together the sounds and sound effects, using surround sound and things like that, that will generate the next twenty years of music. The only thing is, you can’t lose the melody. A lot of people were making music like Stravinsky in his time, but without melody. He built great melodies into what he was doing.

Lyrical Visions

[We diverted into a discussion of a collaboration attempted, not successfully, between Anderson and Christian keyboard virtuoso Michael W. Smith. This led eventually into a deeper examination of the messages Anderson seeks to purvey in his lyrics.]

Your approach to writing about spiritual issues is broader and more poetic than what you could say in the confines of specific theologies.

It’s just a question of growing. When you get more mature, you start to realize how important every religion is. Everybody’s understanding of God is important, as long as they understand that God is also here within and do not forget that, because all your strength and all your power comes from within. It is not outside your physical being. You are already in the light. Your soul is in the light. That’s something that I’ve learned over the years. It’s something I do sing about and hopefully discover as I relay the information to myself through paper and voice and lyric. When I sing “And You And I” [from Close to the Edge], I am still singing to myself: “There’s a time, and the time is now, and it’s right for me, and the word is love.” I’m singing to myself, first and foremost. It helps me become aware of my spiritual connection with Creation.

I read this thing the other day, and it was so perfect. It said, if you don’t believe that you are, in a sense, God and the Light, then you’re arguing with Creation. If Creation believes you to be a light being and perfect soul, why are you arguing with it [laughs]? I thought that was so perfect: You only have to look at the idea to realize that through doubt, fear, anger and frustration, we learn to oppose the idea of our godliness.

That explains why you’ve written less frequently about specific political concerns, as in “Don’t Kill the Whale” [from Tomato].

That’s true, although if you look back to the first album, we did a song called “Survival,” which tells you a story about the nature of things. And we’re on tour singing “Perpetual Change,” which is about how we don’t control anything because the world controls us. If you look at things like hurricanes, we’re not much in control. But also, I hear other people doing it so well. I actually look at Sting and Paul Simon and one or two others who are very movement-conscious, so when I work on my lyrics, I tend to not get too locked into any one particular thing. I try to cover a lot of emotional bases. And I’m still gleaning my work. I think I’m still saying the same thing that I said on the first album, but in a more poetic way.

“If you are true to yourself, you will tend not to meet people who are gonna be bad for you.”

Your lyrics create an uplifting impression, whereas much of the pop music wordscape looks more like a battleground. Are you troubled by the potential for negative as well as positive influences offered in the forum of pop music?

No, because I don’t go near it, I don’t bother with it, I don’t listen to it. It never comes into my jurisdiction. Here’s a good thought: If you are true to yourself, you will tend not to meet people who are gonna be bad for you. You will always meet people who are gonna be good for you. And you will always hear like-minded music. That's the way Creation is: You are always presented with a better day, if that’s what you are looking for.

Sometimes I do ache like crazy to hear some great new music, but then I’ll pick up an album I haven’t listened to in a long time – the last one I’ve been listening to is Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, which is so extraordinary and uplifting. And I’ll thank Creation for presenting it to me. You ask for it, and you’re gonna get it [laughs].

Many of the greatest composers, certainly including Bach, saw spiritual essence and music as inseparable.

Yeah. You see, over the years, we’ve been told that spirituality is a little bit watery. Of course that’s not true, but you’re always gonna get people who are a little afraid of the truth because they’re not willing to look closely at themselves. They’re more willing to go out and punch against something, or even go to war. The idea is that we’re going through transitions. We’re constantly changing. This is a great time to be alive. You only need to get on a plane and you’re a day from going to Luxor and seeing people live exactly as they did two thousand years ago. In fact, you can go a hundred miles away and see people living like they did a couple of hundred years ago.

…

Days with Marc Chagall

The great painter Marc Chagall was the subject of a musical you wrote for the Birmingham Repertory Theater. How did you get to know him to the extent that you could translate his essence into music?

When I first met Marc Chagall, to be honest, I didn’t know very much about his work. I just knew that he was contemporary with people like Picasso and Renoir. I was living in Switzerland at that time. We were making Going for the One, but I also had a bunch of musical ideas that I was hoping to use in creating a ballet. In fact, I had just done one for the Scottish Ballet, so I started thinking, “This is where I’m going now. I’m no longer with Yes. I’m moving into theater. I’m going to become an artiste.” You know: fantasies [laughs].

At that time, I was very interested in Rembrandt and Michelangelo. I started thinking that I’d love to make an album where each song was about a different artist. What happened was, I was there on his ninetieth birthday. I was introduced to him, and his wife Vava asked me if I would come up there for Sunday lunch. So I went up there, and the incredible work that he had done was hanging on his walls. The colors were so vivid! It was so inspiring to sit next to him and to hear him tell me about how he watched Nijinsky dancing to The Rite of Spring in Paris, sitting near Debussy. He started telling me things in a sort of pidgin English/French, and I started scribbling things down.

What things?

Just little notes here and there. I went home that evening and wrote down a lot of what he had told me. I just started to live in a different world. I started to study his work. I went to see it at the museum in Nice, and I spent every other weekend up at his house. It was a great thing to be around one of the last masters.

Were you just hanging out with him at his place? Or maybe you were interviewing him?

I was just listening to him. Eventually I would sing to him. I’d come up with a song that I had written about time: “A story of men of the past, a future secured by the stroke of a brush, curled around the warm feet of the paint that he trusted so well.” That was a song about Picasso – who he hated! He used to thumb his nose at me and say, “I don’t want to hear about Picasso! He was such an asshole [laughs]!” He said that he would sell his soul … Picasso would make money out of anything. He was more into making money than the paint. So I wrote that into the song. Anyway, I went to the local studio, which was about an hour and a half away, in the center of this beautiful forest; it was a thirteenth-century Templars building, converted by this really fine man, a French pianist called Jacques Loussier.

Interesting! He was known for his jazz vocal arrangements of Bach compositions.

Right. We became great friends, and I rented the studio to record this ballet. It’s an incredible story, how I would take it back to Chagall and play it for him. He would sit there and smile. Sometimes he would cry, like when I sang a song I had written called “Mother Russia.” This is another one of the projects I’m being very patient about. I really want to see it performed. I think it’ll have a lot to do with computer animation. I worked last year with a couple of people who could actually make Chagall’s paintings come to life through computer animation. To me, it was about Chagall coming to life on the screen

…

Death & Revelation

At the end of the sessions for The Ladder, your producer Bruce Fairbairn died of a heart attack.

It was a very strange period. We had just finished mixing “Homeworld.” Bruce was never really sure about doing that track. But when he mixed it, he turned around to me and said, “What a great piece of Yes music. I never knew it could come to this point.” And we just laughed. We’d become good friends. He was a very good teacher as well. His attitude was perfect. the people in the band listened to him. Whatever he had to say, they heard him and they did what he told them to do.

There weren’t any of the clashes that characterized some earlier interactions between Yes and its producers.

No. There was instant recognition that Bruce was a friend but also a very good producer, somebody who could say, “Jon? Those lyrics? I don’t want to hear them. Can you change the whole chorus?” And I’d say yeah because, why not? I’ll try anything to make it work. And everybody – Chris, Alan, Steve, all of us – was very quick to change their direction and do some homework when he asked us to.

You were the person who actually found Bruce passed away on the floor of his bedroom. As shocking as that must have been, did you find something in that moment that you could translate into artistic energy?

I think we all had to consider the question of how Bruce would feel about us carryin on and mixing after a couple of days. The interesting thing for me was that his spirit was still there in the house, and he was very excited about where he was. That’s what I told his wife, and it was a great comfort to her and to the manager of the studio, who was really distraught because she had known him for many, many years. We’d only known him briefly, but I just felt that his spirit was there, saying, “Tell everybody I’m okay. It’s amazing where I am. Send them all my love.” And I did. I went up to them, gave them hugs and said, “He’s all right.” I felt that very strongly. … There was a definite feeling that he helped us through this door of emotion that we all needed to walk through. It was a very healing experience.”

####