Like most people, I’ve been through some uncomfortable experiences. I broke a finger in a volleyball game. I’ve had two root canals. I slipped on some black ice, instinctively held my hands up to protect my fingers and thus got a concussion when my head whacked the pavement full speed. As regular readers know, I was socked in the jaw by Van Cliburn. I’ve even had paper cuts!

But I would bear all this and more if I could go back in time and avoid the greatest pain I’ve ever had to endure, that queasiness that comes when you return from doing an interview only to find that something screwed up your recording, leaving you with either fragments or just silence when you play it back.

You would think that, as a professional journalist, I would have learned my lesson the first time this happened. But somehow, even when I loaded fresh AA batteries into my recorder and did the old “one-two, check” test, things still screwed up now and then.

I’ve tried to erase my memories of these nightmares, but a few still haunt me. The bio interviews I did with Cheap Trick and Lady Antebellum went swimmingly, only to sink when I heard the garbled audio on the tapes. Then there was the time I flew home to the Bay Area after spending a day with Fleetwood Mac’s Christine McVie in L.A. My buoyant mood sank when I opened up my suitcase and could not find the cassette on which I’d recorded our conversation. Even now I can’t describe that humiliation that ensued … until I did one last search. This time, I saw a rip in the fabric lining, into which the tiny tape had somehow slipped.

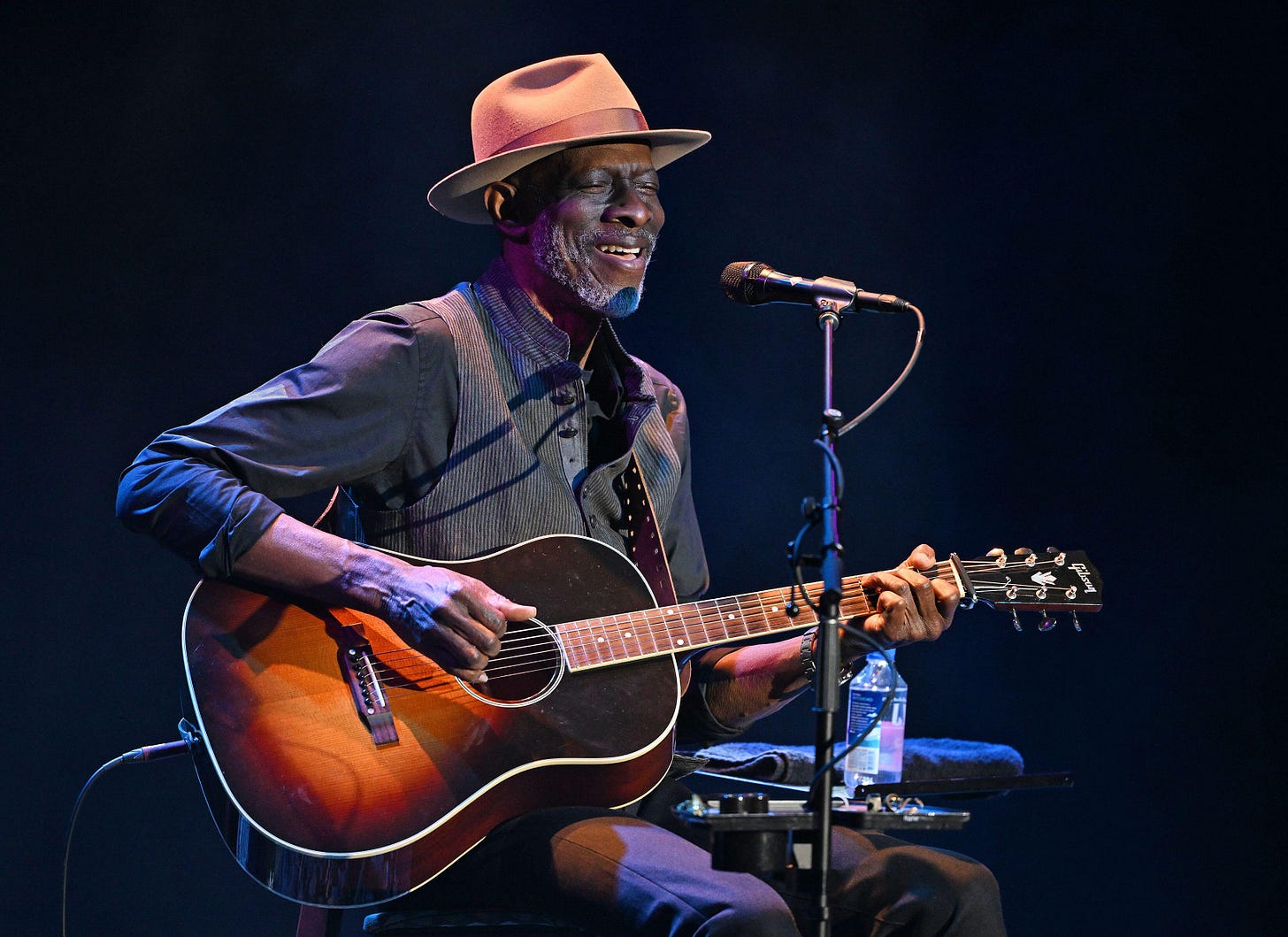

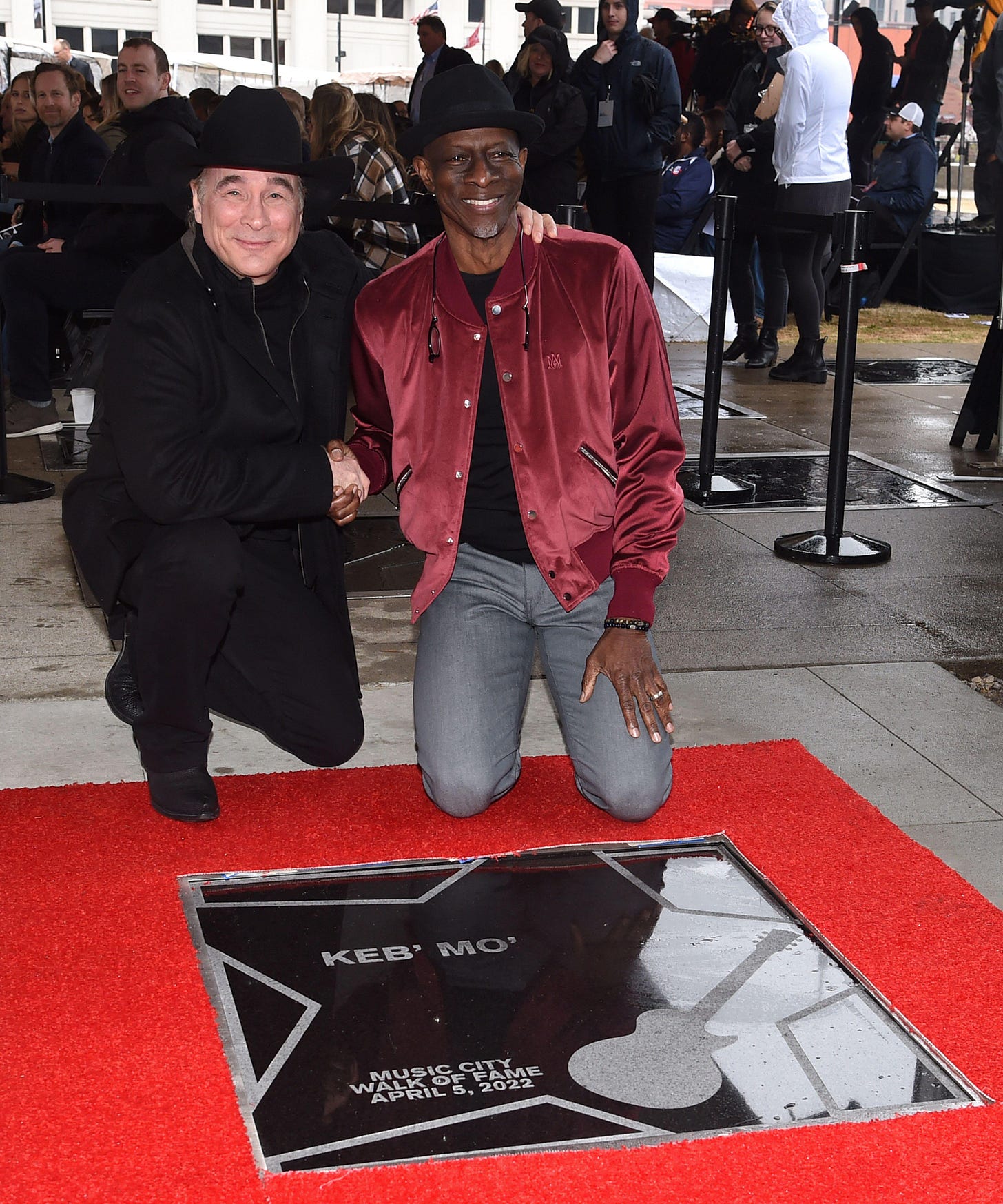

Which brings me to my afternoon with Keb’ Mo’. My assignment from DownBeat magazine was to profile him as well as dig into his new release, which was titled Oklahoma. My preparation involved reading multiple online bios of the artist, refreshing my memory on some of his older and recent work and then going through the new album track by track, two or three times, while scribbling notes in the pad I always brought with me while working.

The notes were fine, the music of course was sublime. I even think my recorder was okay, but as I learned later there was some kind of static in the studio where we spoke that occasionally burst into extended crackles, unheard during our conversation but strong enough to obscure chunks of the transcript.

Several factors allowed me to nonetheless put a good story together. One, DownBeat had given me a relatively concise word count, thank God. And two, I followed a procedure I’d developed after earlier, similar crises: Transcribe whatever you can salvage. Flag the unintelligible passages. Then read through it while jotting down whatever recollections you have of what he said or at least what the meaning of his words were. And finally, you crank up the Google machine and search for names that he mentioned underneath all the racket.

For example, Keb’ mentioned that much of what he learned about playing the blues came from someone named Charles. His last name wasn’t clear, though; in my transcription I made my best guess, which was “Dunning.” It took only a few seconds to look up the key words – Keb’ Mo’, Charles, blues – to introduce me to Charles Dennis, who did indeed play with Keb’ a while back in the Whodunit Band.

One thing I did not do was to invent quotes from Keb’ when entire sentences had been wiped out. For me, what the artists say when into my microphone is inviolable. My approach to transcription is to type out this content verbatim, sometimes even with every “uh” and “um.” Any edits have to have a damn good reason, which might be drunkenness (I am thinking of one specific encounter in New York for Musician Magazine), craziness (another comes to mind), slander or something equally egregious.

That’s how I put this story together. If you like, you can hack through it and then A/B it to the final edit for DownBeat, which you can see here: https://downbeat.com/news/detail/range-breadth-development-keb-mo. It’s neither rocket science nor surgery, but it is what I did for a living for more than four decades. Please enjoy!

****

What were the first steps on this album?

Well, I was supposed to do a record before Christmas of last year. But I wasn’t finished with G-Love’s record yet.I was on the road. When we stopped working in January or February, I didn’t think I had any songs. I was tired of producing. So I called Colin in to produce. [Inaudible plus static.]

We had two new songs. I wrote one with Colin and Chip Estin called “Don’t Throw It Away” — the one about plastic. Then [lots of static]. “Oklahoma” was already kind of rolling. We finished it but I wasn’t going to put it on the record. I just thought it might not fit as a song on the record 3.until Robert Randolph played on the end of it, of a track that didn’t really exist yet. It was a rough with an electronic drum beat. He played on the end of it. When I listened to all of it together, I was like, “Wow, I’ve got to finish this.” I called some guys the next day and we finished the record.

You were going to do this album earlier but some other things came up first.

Yeah, they were already rolling. When I get on other projects, I can’t let it burn until [static].

Now that the album has been out, do you listen back to it and hear things you might wish you had done differently?

I think I pretty much got it like I wanted it. I think I might have changed the drum groove just a little bit at the end of “Oklahoma.” [Inaudible detail on what might have been done.]

What thought goes into whether you or someone else will produce an album? If the job does go to someone else, how do you choose who that will be?

In the beginning it was John Porter because he brought me in; he got the record deal for me. For the third one, which was Slow Down (1996), I was feeling like things were just going too fast for me. I’d won a Grammy [for Just Like You, 1996]. So I worked with my writing partner John Parker on that one. The engineer was Ross Hogarth. There were a lot of obstacles to that because I was meeting a lot of resistance. I had never produced a record before. I had produced music, but I hadn’t produced a record.

“I’m more critical of myself than anyone.”

What did you learn from that project that informed your future production work?

One thing is that you have to make all the decisions. I like making my own decisions because I think I make more capable decisions — not because other people aren’t capable but because it’s me. I’m more critical of myself than anyone. So my decisions are going to be [inaudible]. I don’t make them as quickly but I think my experiences at making decisions make them work better for me.

The next one I produced was Keep It Simple (2004). When I started that one, there was no one helping me. So I called a guy [or: the guys?] I wanted to call. [Inaudible, including a mention of Greg Phillinganes]. They came in. And I did everything [in terms of production]. I even mixed that record in ProTools, did all the fades and all the rides and all the everything [inaudible]. No one would go in. I had to trust myself. I had to learn how to trust my decisions. When the record came out, it was all cool. I knew I could put my trust in myself. It also made me more critical of what I’m doing.

After that I produced a record called Peace: Back By Popular Demand (2004). Then I think I did on [inaudible]. At some point in my record deal, in my last record, which was Suitcase (2006), I started where I’d left off, with John Porter. We’d never had a rift between us, no rift whatsoever. But I just wanted to express myself. On that record, there were things I kind of had to let go of when he mixed it. There were some things in the mix I would have done differently. There were also things in the mix that I love. A lot of times I go back and listen to those things I would have done differently and there’s no problem. It’s all over the map.

And Tajmo: [sounds like: put a lid on that thing] [laughs]. I’ve found that a great record is about details: the right notes, the right tempo, the right dynamics, the right tone on every instrument. Because you’re making a painting — an audio painting — that’s gonna be here a long time. Sometimes it’s just [snaps his fingers]. But for me, it’s about putting more attention to details.

One of my favorite records is “Staying Alive” by the Bee Gees. The horn arrangements, the string arrangements, the guitar parts, the bass parts — it’s a masterpiece. And Saturday Night Fever is one of the top-selling records of all time, like Thriller. Those records are very, very detailed.

A lot of times people say, “Don’t overthink it because you’ll lose the vibe.” Well, I overthink the shit out of it. You gotta recognize, when you’ve got a hit like that, you’ve got to be able to listen to it and figure out if I did that right.

A lot of jazz artists focus on capturing the moment more so than the details. Pop music is the opposite: It’s crafted so meticulously. You’re trying to walk that line down the middle.

A great classical piece, a Beethoven piece: They were constantly fixing the chart until it worked. When you hear a great symphonic piece, there’s not a hair out of place. At some point rock ’n’ roll evolved to where the pinnacle was probably Saturday Night Fever. That was the pinnacle of pop music. In the Eighties they took it to another place. They made some beautiful pop records in the Eighties.

Then if you go back and listen to Kind of Blue, I guess that was a very quirky record. The day was right. Everything was going right. It was maybe the greatest jazz album of all time.

The Right Producer

Why did you bring in Colin [Linden] to produce Oklahoma?

The thing about Oklahoma is, Colin’s my friend. He’s fun to hang with. Also, he brings good energy. When you’re recording, I feel that everything gets recorded. The mood in the room gets recorded. When the mic is on, it’s in there.

This was the first time he ever produced you, though you go way back as collaborators and friends. How was that?

Well, it took about a week and a half to get a groove. We were working on sounds and setting the tone for it. I’m terrible when I start my process. I’d like to just put on a smile and do it, but the way I go at it, I get this strange [sounds like: sound that I was doing it for] for the first time. I’ll go in and try some stupid thing [inaudible for a while] because I can’t really dazzle you [with a verse?], know what I mean? But Colin wanted to direct me, even though I’m kind of undirectable. I got my own process. I could tell he was getting frustrated because he’d hear my ideas and go [strokes chin in thoughtful doubt], “Hmm [laughs][.” At the same time, the ideas he put forward made a huge difference on the record. For instance, the organ on “The Way I”: That was brilliant. He had a great idea of putting this little pause before I sang “Heaven” in “The Way I.” Also, he brought in Jim Hoke. Of course he’s a great guitar player too. More than that, he’s got great ears and a great sense for what really feels good. But especially, he was supportive of what I’m doing. And I’m really hard to please because I know what I want almost all the time.

So he made some calls — detailed calls.I can’t really put it into words. He did enough of those little things that he added another meaning to it. [Long inaudible passage.]

I’ve thought about what it would be like to make a record with Rick Rubin. I never go for the high dollar, but in the record business he’s kind of like a shaman. The things he’s done are very cosmic. But Colin is really good. He’s got it figured out. [Long inaudible passage about Colin’s skills.]

In my interview with him, he described what he sees as the difference between your aesthetic and his: “Kevin and I have pretty different aesthetics. He likes things to be very clean. He doesn’t like a lot of room sound or deep bottom. If I don’t hear a certain amount of room around something, it makes me nervous.” He also says that your “facility was kind of built to serve that aesthetic, just like mine was built to serve mine.”

Well, I’m into feng shui. When you sit at his board, your back is to the front door. And it’s very new. He’s got a lot of drywall in there. You can make a record in there. He loves vintage things. I like new things. The way I look at it [pointing to racks of modules], that thing is new. I like technology. I’m not so into “it’s gotta be vintage. I like really clean, pristine records. I don’t like clutter. If something’s old and it sounds good, I’ll use it. But if it’s just old … [laughs]. See, I like modern records. I’m already playing the blues, which is older than dirt. People are used to listening to really fantastically recorded pop records. So I don’t want to go back. Some people do. If it’s done right and it’s clean and the performance …

How do you feel about the debate over analog versus digital?

It’s all just noise. [Inaudible.] The last analog thing I did was with Marty Stuart on the Johnny Cash tribute record (Kindred Spirits: A Tribute To The Songs Of Johnny Cash, 2002). But I wouldn’t do an album on tape. I don’t trust the tape! Every now and then, you get a bad roll of tape. When they made Saturday Night Fever, they had to make it quick. When Fleetwood Mac was making Rumours, they were making a masterpiece too. But they were rolling that tape back and forth for two years until you could almost see through it. Now, with ProTools, you can roll that music as much as you want.

It Starts with the Voice

Don’t you play some classic guitars?

No, it’s all new. [Keb’ talks about his Resonator guitars and the guy who makes them, I think up in Montana.] Oklahoma is one of the first times I feel like this might be my best record. That first record was a long time in the making. For this one, by the time I got to the studio, all the things had been worked out [laughs]. It started like all my albums: It was meant to be an acoustic record. So I put the guitar on first, to a click track — actually, scratch that. It starts with the vocal.

You do it a cappella?

Oh, yeah [laughs]. It’s not a master vocal. It’s just something that I can wrap my guitar around as tight as I can when I accompany it. Like, for “This Is My Home,” when I got that swing in the guitar, and I come back with a vocal that’s right there in the groove, then everything else falls into place. I can even leave some of the notes out of the voicing on the guitar. And no one really knows that you’re doing that. It may sound flawed because the playing is flawed. But the composition part, I want it to be really right and tight.

Bach was right. When I was at LACC I had to study a lot of the Bach chorales. [Inaudible section, where I think Keb was expressing his thought visually.] My teacher would say, “You always do them wrong — but they always sound right [laughs].” So I can pick two notes on the guitar and damp the sixth string. Now it becomes a piece, not a song.

How different is your final vocal from the scratch vocal?

It’s refined. It’s in tune. I might go back and change a few words. The groove is even more intense. Then it has a complete feel to it. That’s where it starts — the feel.

Do you sometimes go back and tweak your guitar after getting the final vocal?

I may go back and do it like [inaudible] piccolo Nashville steel guitar But the tuning would not stand, so I went back and capoed [inaudible].

Talkin’ Taj

In talking about when you and he met, Taj said he was “glad to have some company out here in this desert.”

He was out there all by himself [laughs].

Why do you think rural blues connect with you?

I always tell people, music has been chasing me my whole life. I wanted to go out for a career, but music kept chasing me. I first became aware of Taj Mahal in high school. He came and performed at an assembly. Then two years later, my friend Robert Mims [?], who I haven’t seen for years, he said, “Man, I bought this four-track tape. I don’t really like it. You can have it.” It was Taj Mahal. I put that thing in my four-track and wore it out over the next two years.

Fast-forward to the Seventies [Keb’ says something about a beach], you know, girls and doing stupid Twenties stuff [laughs]. I worked my way up through the Seventies and got signed to a Casablanca/Chocolate City Records deal. And, man, that thing flopped. For two years I didn’t have any work.

Just club gigs?

Maybe. I was playing for [inaudible — sounds kind of like “Mister Bernstein”?], writing songs. To make a long story short, I became a member of the Whodunit Band. Now, I’m, like, 31 years old and ain’t nothing happening. I work during the day and at night I’m playing the blues — learning how to play the blues, from Charles Dennis.

You were learning acoustic?

No, electric. I didn’t pick up an acoustic until the late Eighties. When I was playing the blues, I was paying attention to all the things that were going on. I got Monk Higgins as my mentor. [inaudible couple of sentences.] So we did this thing. We made a record. And I started playing the blues. I started getting gigs and things picked up later on. That’s how it started up.

It was like a conscious career decision to play the blues.

Yeah. And I just followed the yellow brick road [laughs].

So through the music, looking for a way to pay the rent, you got on the yellow brick road and found yourself.

Yeah, and I got tired. I was married. I had a kid. I went to electronics school and learned how to build circuit boards. My plan was to get a job at Roland: Electronics and music? That’s a perfect combination! But then I said, You know what? Fuck it. I’m staying with the blues. It felt pretty good. [Inaudible.] I think that lit a fire under him.

Learning the Blues

As your musical direction got clearer and you realized this was taking you somewhere closer to yourself, how did you go about learning to play blues authentically and, for you, personally?

[Static pops up and over Keb’s words.] … offer to do a play called “The Rabbit Foot Minstrels” — Ma Rainey and her minstrel show. [Inaudible.] He gave me this cassette. [Inaudible.] Piedmont blues, Chicago. We had to rehearse [inaudible]. I couldn’t play slide. I went down to McCabe’s Guitar Store in Santa Monica and had lessons. I learned how to do it.

When I was a kid, “blues” meant electric guitar, often played by British guys. Did you feel like a missionary of sorts for country blues, which was relatively neglected?

Well, when I was playing with that Whodunit Band, they [inaudible] in the club scene, one or two nights a week. Everybody who was living in L.A. would come in, from Big Joe Turner to Billy Preston. Merry Clayton would come in. People who were getting out of college would come in. The audience was [inaudible] singing at the church. [Inaudible.] “You should listen to this Eric Clapton record.” “I’m not listening to any Eric Clapton record. B.B. King is the blues.” I didn’t need the record to get that. I knew Eric was good. But Eric would even tell you, he ain’t no B.B. King. It’s like, I would tell you, “Don’t listen to me. Go listen to Taj Mahal [laughs]. So I took it on. Now there are opportunities there, feeding me, doing this thing. Now I’m 48 and I’m just figuring it out. I was playing behind singers in clubs [inaudible; sounds like: I got a chance before teaching] people how to play the blues. So I play … I started playing blues so much that they forgot I played other stuff. [inaudible] “… they'll say you’re just playing the blues.” Well, that’s okay [laughs].

Do you ever feel pressure to conform to traditional blues convention rather than push it too far.

Not at all. I had studied my jazz theory. I had studied all that stuff. To me, this was a huge opportunity to go in while knowing the boundaries of what was blues and what was not. So you know how far you can go out — and then you come back. It’s like, I can do “Beautiful Music” and after that do a blues. I constantly keep jumping genres with consistency. I like to think I can do that. If you jump genres, you gotta be good. When you’re doing an album like that, it’s gotta be like a DJ mix; you just go with the same person.

You are so spiritually connected to this music. It sounds like you were born into it. Yet you got there by study, work and concentration. It fits into that idea of your being so detail-oriented.

What happened was, I [sounds like: presumed] my true beginning of my real world there. But I had all this background, a certain amount of experience. I’d been a recording/session guy. I’d been in orchestras and marching bands. I’d been on the road. I felt like a Memphis type of guy [?], playing the blues and so forth.

You’d been a staff songwriter at A&M too.

Yeah And now I got this thing I’d been dodging my whole life.

Why were you dodging it?

I was from L.A.! When I got [sounds like: raised], people told me to stop [laughs]. They said, “Man, you’re gonna starve to death with that stuff.” Well, I didn’t give a fuck. And it worked.

“Don’t Throw It Away” had to have been recorded live.

We did it right here. Taj played the bass. Colin the little piccolo. I played mandolin. I had overdubbed an acoustic.

Did you have drums in here?

Yeah. We did that later, with a click track through headphones. It’s very rare that I don’t use a click track. I look on that as my insurance policy, because I’ve wrestled with tracks that are all organic. And something’s off. With a click track, if it feels good, you can always move things around. Tajmo had a click, but Taj didn’t like it. He wouldn’t do it. But he doesn’t need it. I used a click. With Taj, you cannot move [inaudible]. The way he sings, his phrasing is so great, it defies a click. I would go like, “How does he do that? It fits right in the groove.” I think it’s because Taj is always in the moment. A lot of people can’t maintain that enthusiasm [static pops up].

… Jim Keltner, that famous drummer from the Eighties, he likes to do one take. With him, you have to get it in one take or maybe two. He played on a song called “Change,” from The Door (2000). He did this take, with a shaker in one hand and playing ride cymbals. And when he got done with it, Keltner just said, “That’s it” and left.

But I’m not quantizing everything on my laptop, so it’s still going to be quirky. It’s still people playing it. Sometimes you need things and sometimes you just let it … [Keb’ makes a whooshing noise’. I’ve learned that microphones are really what make a record. If it doesn’t feel right, I’ll move the bass player down a nickel to the right..

Have you always had this attention to detail? Or did you develop it as you gained experience in the studio?

I was always kind of like that but it evolved a lot when I got into ProTools. But even back in the day, back in the Seventies, I was always … I’m making a funny face here [laughs], like, “Do that note but leave that note out.”

“I’ve pissed a lot of people off.”

You’d ask the guitarist to mute one string in a chord?

Usually the bass. Or, “could you not play the bass on the piano? Can you use the right hand instead of two hands? Because you’re clouding my bottom.” I’ve pissed a lot of people off [laughs]. When I was in L.A., if you called someone for a gig, people didn’t turn gigs down. [Inaudible: I think he describes how people would nonetheless avoid working with him.]

Man, I had nothing! These kids could read music. “Maybe you could do something else. But I don’t have anything else. This is it! You can get mad all you want. I’ll call somebody else next time. [Inaudible] did that. What it takes to move people’s physical boundaries and emotional boundaries, the mathematics of it. for me, it’s not work.

If you slow the tempo down just a beat below what people expect, that builds tension in the audience.

Mmm. Also, if it's slower, people can digest it a little bit better. Like, my sister and I went to see George Clinton’s Parliament in L.A. And she was like, “Everything seems slower!” It was! Your body responds to that.

When Otis Redding did “I Can’t Turn You Loose” in Monterey, he bumped it up nearly to double time. It just didn’t work for me at all.

The feeling back then was that it made it more alive when you speed up and get louder. [Very distorted audio for nearly a minute.] So we were talking about the steel band. So many times I’ve just been in the right place at the right time. [inaudible] or even now: this record, at my age having a record that, of all the records I’ve made [inaudible]. And when I’ve made a record, it’s harder now to get people’s attention, with all those things [inaudible] to play on the radio [inaudible] the amount of people there. You have to kind of hypnotize [?] [inaudible]. Curiosity will get you.

The first track, “I Remember You,” opens with a guitar lick that absolutely demands attention.

[Very distorted here.]

It sounds like you’re on the I but that suspended chord drags it up to the IV while you’ve still got that I feel.

Yeah [laughs]. We took our time. I guess we took a week and a half for Colin and me to get our feel right for working together. But we got it.

Tell the Truth

Several songs on this album have a strong social commentary. “This Is My Home” is the most beautiful of those.

That wasn’t even originally the title. But I wanted a title that would spark curiosity.

Is music returning to the role it played in the late Sixties and early Seventies as a voice of passion and expression about what’s going on in the world?

That was a great time — you were there. You waited for some new album to come out. You got it and called you friends: “Hey, I got it! Come on over!” But now I don’t know how much attention people are giving music anymore. I don’t! It seems like people are just listening to it at the shows. Social media is now what music used to be, a way for people to stay in touch. That’s what got all of those people out in the street in Hong Kong, I don’t know if they’re gonna win — they’re up against China [static flares up] civil rights.

“I do my records for real people.”

I approach issues now very carefully — not because I’m scared to say anything but because I want them to be heard. I have to find a very careful way of saying things. I do my records for real people. I put myself in them. Otherwise you get, “Get out of politics! Just stick to music!” People don’t want to be challenged socially. Like in “Oklahoma,” I addressed an old atrocity [inaudible]. So you’ve got to be very careful or else you’ll push them away rather than bring them in. And our job as musicians and artists and journalists, people who communicate in a public way, is to spread the news and to get people to think.

How did Dara Tucker help you get the right feeling and focus in writing “Oklahoma”?

I need my songs to be authentic. It was the day after New Year’s when she came over. I said, “Where are you from?” She said, “Oklahoma.” Bam! Once again, right place, right time. I had this idea and we just started writing. We talked about what’s great about Oklahoma.

You didn’t want to just get that out of Wikipedia.

Well, some of it came out of Wikipedia. I read about the tribes that were there and some other things. [Inaudible] on the road, about Black Wall Street. I was reading Charlie Wilson’s book — he was the lead singer of the Gap Band. Now he’s the prince of R&B singers. Charlie is from Oklahoma. Vince Gill, Garth Brooks: Oklahoma has a rich musical history. My favorite guitar player, David T. Walker, was from Oklahoma. When a tornado runs through it, it’ll knock you right in the head. So in Oklahoma, in the aftermath of a tornado [static flares up].

So I got an appreciation for Oklahoma. It’s like, “Now I know it’s a great place. Now I can write ‘Oklahoma.’” [He sings and taps the beat: “O-k-l-a-h-o-m-a! Everything is going our way.” That’s the cheer from Oklahoma State. We put it in the song.

###