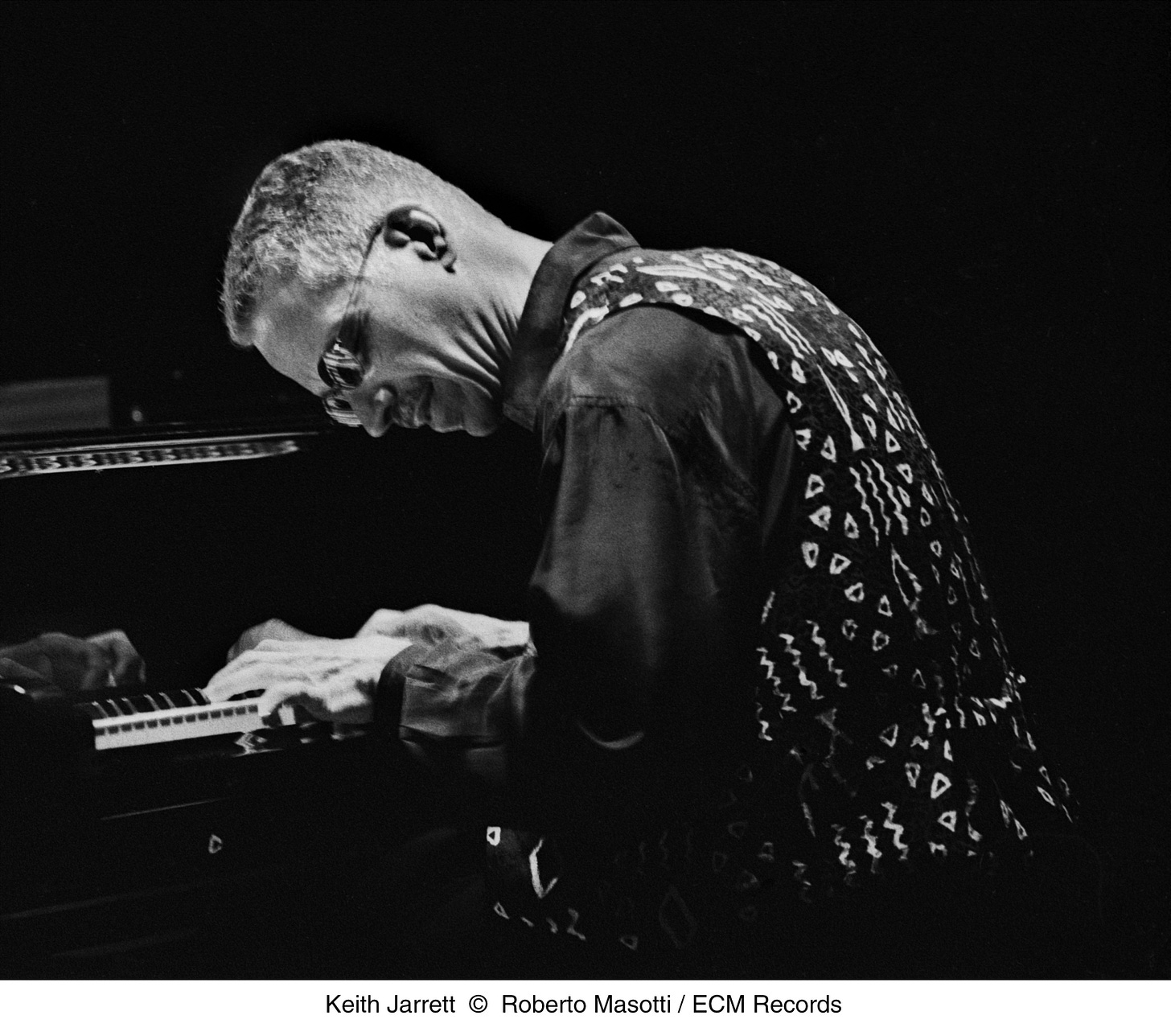

I remember both of my interviews with Keith very well. This shouldn’t surprise anyone who has imagined what it must have taken to achieve all that he has done. His explorations into complete solo improvisation at the piano demand a discipline and daring that few of his peers have ever reflected in their work. The so-called “young lions” movement, spearheaded by Wynton Marsalis, drew unanimous praise for its dedication to revisiting and invigorating older jazz traditions; from Jarrett, it drew severe disapproval bordering on scorn. All of his contemporaries and those who followed in Miles Davis’s bands surrounded themselves with synthesizers and other electronic keyboards; Jarrett abhorred them. Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, and other innovators entertained onstage; Jarrett would frequently stop whatever he was playing to scold someone in the audience for daring to cough or otherwise impair the attentiveness he demanded.

He could be prickly, no doubt about it. For our second interview, I drove from my Manhattan hotel out to his home in rural New Jersey. This was pre-GPS, so I had only my scribbled directions to guide the way. This was why it was always my plan to allow plenty of what I called “getting lost” time. As it happened, I got to his place way ahead of schedule. Having been admonished by his publicist to be prompt, neither early nor late, I went a little farther until I found a diner where I could order some coffee, go over my notes and keep an eye on the clock. When it looked like I’d better head back to Keith’s, I paid up and headed back up the road.

Coming up the driveway, I saw Keith sitting outside on the porch, playing his recorder in the pristine daylight. I shut the door, walked toward him and then checked my watch. “Uh-oh,” I announced. “I’m about two minutes early. Hang on.” Then I returned to the car, got back in and re-emerged right at the top of the hour. I knew Keith already, so he reacted just as I felt he would, with a grin and a laugh. We were off to a good start.

Inside, he showed me around his place, which was comfortable but not ostentatious: well-kept, cozily furnished. Eventually we made it to his studio, where he showed me his two nine-foot Steinway concert grand pianos. He gestured toward them. “Go ahead, check ‘em out.” I went first to the nearest one, played a few things, and said something like, “Good God, this is gorgeous!” Its tone was sonorous, the bass notes rumbled without any buzz.

He kept grinning. “Now try the other one.”

Also a great piano, but the touch and the timbre were a bit lighter. Keith acknowledged this and then identified the first as a Hamburg piano, made in Germany. The second was built in New York. When asked which one I preferred, I said, “The Hamburg is almost too beautiful, at least for me to handle. I can relax a bit with the American one.”

“You’re right,” he replied. “The way I put it is, you can play the blues only on the New York Steinway.”

For me, the thing about Keith is that he knows he can be annoying. I would go further and say I think he enjoys being that way when he feels there is a need to be, when it calls attention to whatever offense needs correction. In this way he reminded me of people I’d known in high school and college — the ones who loved to argue for sport, whose efforts to express their thoughts as persuasively as possible led sometimes to grammatical convolutions, over which they would chuckle at their own contortions, which sometimes came out like Zen kōans: inscrutable but also provocative. They made you want to talk more, later into the night. I really liked those kinds of guys. Hell, I was that kind of a guy myself in dorm room bull sessions. What’s not to like?

A final thought: Like many if not most of my interviews with artists, this one centers on a specific event — in this case, the release of his ECM project Spirits. What’s different here, because I knew that Keith was a big-picture guy, is that we don’t actually get around to talking about the album until well into the conversation. Instead, we constructed one of my favorite interviews in terms of not just sticking to bullet points but by listening to each other and letting our words follow wherever each other’s thoughts suggested. By creating a context in which Spirits could be discussed at a deeper level, I sensed that Jarrett would happily follow along. It was the right thing to do, because whether reconsidering the implications of his own virtuosity or of the piano itself, that’s how he likes to work. As do I.

***

Rumor has it that you’re reconsidering your relationship with the piano and thinking about getting into more ethnic types of non-keyboard music.

Well, when you say one thing, you can’t say the other side of the coin. If you use words, you cannot help but speak from half the truth, if not less, because you can’t define the whole thing. So if I say something about the piano, I might mean more than that.

But what has been going through my mind is that even the piano is not a primitive enough instrument that I can consider it essential sound. The more I’ve been alive and a musician, the more I realize that essential sound, if there’s a way of forgetting what I might mean by that for a minute, is the only sound that really touches you despite yourself.

Let’s say that sophisticated sound is what’s on the other side of that coin. That touches you through its own complexities. By the time those complexities have been eliminated, so has half the music. A master flutist, let’s say, from a so-called primitive country might be able to touch you right away with his sound, without you even knowing whether he’s a good player.

Strangely enough, most of the best jazz players have played wind instruments. There are the pianists and the drummers, but in jazz the tendency is for music to remain more connected to that essential sound. In classical music, it’s like getting a sound you want as an ego that’s writing a piece. That’s different from what I’m talking about.

Essential sound, to you, is not a tangible component that you can study on an oscilloscope.

That’s right. And it involves what I would call the value of the sound itself. If you hear a sound, you automatically are affected by it. If you hear a sound that has value, in the sense that I mean, you are not only affected by it, but you gain from having heard that, even despite yourself. So the more sophisticated the instrument a musician uses, the more he has to be clever about how he gets around to having that effect on the audience. And the more clever he is, the more he’s playing into the intellectual, technological world that seems to think that all things can be solved by that piling up of things.

That same point was made a few years ago in an interesting book by Dane Rudhyar, The Magic of Tone and the Art of Music.

The funny thing about saying the same things is that there’s a much greater chance that they don’t have any idea that someone else is saying them than there is that they’ve heard, because to get to be able to say that and mean it means you’ve spent all your life digging that way. The other way is reading everybody’s writings on the subject and coming to some conclusion that so-and-so is right and so-and-so is wrong.

One attribute of the wind players you refer to is the high degree of organic nuance they can bring to their sound, whereas the piano sound is fairly locked in. Does that tie into your perception of essential sound?

Yes. Let’s say that locking in is something that’s not so good. If you have sound locked in a space, then it can’t get out of that space. It’s less moving and less able to touch a human being whose body is constantly changing. So the locked-in thing doesn’t have any relationship to the human being.

Now, I still consider myself a pianist. I still love the instrument. But my responsibility is as a musician, not as a pianist. If my responsibility takes me away from the piano, that’s when I might very likely say something like, “I’m not so interested in the piano at this moment in my life.” As a pianist, you have to phrase impossibly. I still do that, which is one reason why I still can play the piano and not have to move away from it more often. There are still some magic things the piano can do that are not pianistic. You can still speak through the instrument.

You’re not about to undergo a permanent separation from the instrument, in other words.

Nothing is permanent in anything.

But even given all the wonderful attributes of the piano, some of your physical exertions as a player seem to reflect a struggle to make the sound of the instrument more organic.

Yes, that’s exactly right. I mean, I’ve never developed a philosophy about my movements. Everybody else does that for me. Mostly people think they’re something that’s grafted onto the music. If they could ever see the trio recordings in the studio, with no audience watching, they’d realize that my movements are not grafted on because that stuff is happening anywhere we play [laughs].

They can hear your vocal obbligatos to your recorded improvisations, though.

Yeah. That’s part of the thing too.

Have you ever seen a video of yourself playing and been surprised at how it shows you?

Not recently, although there’s a solo concert that PBS broadcast that was pretty graphic.

Was watching that broadcast something like watching some player other than yourself in the act of creating?

Yeah, I could say that. I’d rather be doing it than watching it [laughs].

The Educated Listener

All of this is especially interesting given your recent explorations of written repertoire. In a sense, are you like two pianists in one package, with what seem to be opposite processes involved in your approaches to improvisation and to playing from notation?

At a certain level, I think you could say that. I do feel that sometimes myself. However, essentially — that word again — it isn’t true. It’s all part of the same flow.

To give tiny examples, I asked Lou Harrison if he would be interested in writing a piano concerto. He finally did, and I think the piece is great. One of the problems with it, though, is that it expresses some of the things I’m talking about, and no other musicians who happen to be orchestra players are interested in that. They don’t know what that’s about. They have a job and they think whatever they think about this piece.

What’s really happening is that I’m able to use Lou’s piece to say what Lou and I would both like to say about the instrument and some of the assumptions we make about what good and bad music is. The way it seems to me now, there are people who feel that the best music is the most boring music, which allows them to go about their business and not have to listen with any amount of energy. Then there are other people who think that it should be so cerebrally ultra-interesting that, other than that, nothing in the music exists. And in the middle somewhere, the core of listeners must still be jazz listeners.

“To me, valuable music should not allow you to escape from your own heartbeat.”

Do you mean they are or they should be jazz listeners?

That’s where the jazz listeners must be. What good listeners listen to is closer to what is there than what classical listeners traditionally listen to or what minimalists are listening to now.

By “what is there,” do you mean they are hearing the music as it happens more than other listeners?

Yes. They’re aware that at any second something might happen that they’re not prepared for, so they have to be open. If they’re listening to a player from whom something valuable has come out, they listen with a certain openness that differentiates them from other kinds of listeners. Let’s say they’re willing to sacrifice their preconceptions for the sake of seeing what this person is going to do.

In other words, the aware listener at a jazz performance, or at any improvisational performance, has to be in real-time interaction with the music, as opposed to being slightly displaced by his or her expectations.

Yeah. To me, valuable music should not allow you to escape from your own heartbeat, whereas in the Western world over the past several hundred years, music means an escape from that, instead of a more vivid seeing of that. That’s the one thing about minimalism that, in the beginning, caused people’s interest. Instead of seeing this interesting thing that takes them out of themselves, they were suddenly thrown back upon themselves.

Minimalism also sets up listener expectations and then thwarts them with unexpected changes in the patterns established by the music.

But if expectations shouldn’t exist, then we’re going back to being locked into expectations. At every point in a human being’s existence, he’s locked somewhere. His responsibility is probably to stay aware of where that locking is taking place in each moment. A good listener would realize that, at any moment, that happens at all levels. In my solo concerts I might have played a long section that would be boring to somebody, but if they allowed themselves to be bored …

I’ve asked many people about what happened to them during specific parts of my concerts. And no matter where they were sitting in the hall, they would tell a similar story if they were listening or if they knew what I was talking about. First they went through this thing of, “Now what’s going to happen? I wonder what’s going to happen next.” Then it starts to get boring: “How long is this going to go on?” After they get through this stage, they realize that something is happening anyway. If it stops there, that’s minimalism. But after that experience you could say, “That was that,” then something else automatically shows up in the music.

Do the responses those people share with you parallel your own experiences as the performer at those specific points of the performance?

Yeah. I remember vividly saying to myself, “This should change.” Should? Why should it? I don’t know. But it should. Well, that’s not enough reason. So it stays there. And I start hearing different things, let’s say harmonics, I’ve never heard before in the three notes I’m playing.

It’s like going back to a vegetarian diet after a fast, where you realize how strong some of those tastes are that you take for granted. If you stay on that fast, you don’t learn that; you don’t have that experience. You get off the thing and you never get back on, so you have nothing to relate to in terms of what it was about. It may be nice for you physically, but that’s not all we are.

When you’re playing, are you thinking at any level about making your music sound “closer to the heartbeat” of your listeners?

No, because if that’s close to me, it’s automatically that close to them since we’re all heart-beating. I’m not saying that there’s a particular thing I should do for them. I’m saying that if I do it for me, it’s automatically done for them.

Other artists might say the same thing but are less successful than you at reaching audiences.

Then they don’t know themselves well enough. We can all say the same words. You could have another interview today with somebody who says the same things I do, and you would say, “You guys agree.” We might agree with words; it depends on whether we know what we’re talking about [laughs]. If Ronald Reagan and I agree on something, you could still hear the differences if he decides to play the piano.

The Elusive Magic of Sound

How did you become aware of the piano’s limitations as a source of essential sound?

As long ago as the early Sixties, when I was playing with Charles Lloyd, I was talking to people about giving up playing the piano. One note at a time seemed fine. Sometimes I’d be playing just one note and it seemed so good, I wondered why I’d need the whole piano. This was something I could do without the piano — probably without a key! I could just use anything that was lying around.

Okay, let’s say that was ’64 or ’65, about twenty years ago. Naturally, I was at an age where, if I did that, that would be the end of what I was trying to do. I must have realized that whatever energy I wanted to use had to go somewhere, so since piano is my instrument, I recommitted myself to the piano.

“Sometimes I’d be playing just one note and it seemed so good, I wondered why I’d need the whole piano.”

There have been several times since then that I’ve had that same realization. One of those times was when the solo concerts ended. But each time it’s greater. Each time it’s telling me something. So I ended up having a harpsichord built for me. And a clavichord on which I started doing Baroque music, all the while not realizing that what I was doing was testing the essential possibilities of other instruments. In a way I was testing a theory I had had for twenty years.

What theory was that?

That the piano isn’t always the right instrument for what I hear. When I had my early trio, we always fooled around on lots of different percussion things — it was called “fooling around” by most people. The difference now is that the next release on ECM is going to be that element taken to one hundred percent of what’s on the double album.

Meaning there will be no piano on the record?

Meaning that when piano is used — and it’s used incredibly little — it’s used only to convey the harmonic structure in the background. It’s never used as a major instrument at all. And that’s not the only thing that’s different about the album. Another thing is that it’s the opposite of a state-of-the-art recording. It was made on two cassette players. It has lots of wow and flutter. The overdubs were made on cassettes.

What role did [longtime producer] Manfred Eicher play in this?

Sometimes Manfred and I send each other music that we like. When I sent him my tapes, I didn’t include any notes with them. He knew they were what I had been working on, but I never asked him whether we could do something with them. I waited for a feeling from him until he wrote back one day and said, “We have to do something with these tapes.” I said, “You’re kidding! How are we going to do that? These are cassettes!” He said, “Don’t worry about that. I understand that you couldn’t have done this anywhere but at your studio. You couldn’t have had an engineer there twenty-four hours a day for a month, and you couldn’t have used more sophisticated equipment because you wouldn’t be able to just punch these machines in and forget about it.”

Is this the first record where you’ve overdubbed parts?

No. [Bassist] Charlie Haden and I did some overdubs on Survivors’ Suite. I did something long ago with lots of them.

Philosophically, you wouldn’t seem too keen on punching out wrong notes.

Oh, no, it was nothing like that. The interesting thing is that these overdubs on Spirits were done out of necessity. This is like the difference between a hunter now and a hunter in the days when food from the hunt was needed. I had a feeling for what I was going to do. It couldn’t have been told to anyone else, so I couldn’t hire a tabla drummer. I had to be the tabla drummer. I couldn’t hire singers or flute players. The whole idea wasn’t what notes were being played. The idea was what they are being played through.

What kind of instrumentation did you use?

A Pakistani flute, a lot of different recorders, little toy instruments … whatever I had around the house. I didn’t go shopping for anything. I decided that this music had to be done with whatever was there. Some tablas that couldn’t be tuned played a big role.

Why couldn’t they be tuned?

The humidity had changed, and that fact suggested what I should do with the piece. Soprano saxophone became a part of it. There were a few other things — a little guitar …

What’s especially intriguing here is that even your critics in the past have acknowledged your technical mastery of the piano. In looking for a more essential sound, as you say, you’re embracing instruments on which you don’t have a comparable virtuosity.

That is what I think is so interesting about these tapes. I don’t think anyone is going to think about how well or how poorly anything on the album is being played. There’s such an atmosphere that it overrides any of that. I wasn’t even concerned with keeping time perfectly. In fact, sometimes it was important that the time be more like heartbeats, and heartbeats are not perfect. So in a way it’s an answer and a rebuttal to where things are at now — let’s say, a level of incompetence that doesn’t allow anything but the notes to come through, like all the saxophone players we hear these days, who sound like whoever they sound like these days. It certainly isn’t Coltrane anymore. They all have the same sound and the same phrases. Because of my limitations on the instrument, I was able to play it better.

The point is not that David Sanborn sounds the way he does. The point is that everybody sounds like David Sanborn.

Yeah, right. Well, I wouldn’t have used David Sanborn as an example. Jan Garbarek was involved there for a while, and Gato [Barbieri].

Along that same line, Jack DeJohnette seems to de-emphasize technique in his drumming on your Standards albums, perhaps for similar reasons.

Let’s put it this way. I’ve been privileged to hear pygmy music. One of my friends works for a Belgian museum, and he records pygmy music for them. When you listen to it, or to American Indian music, would you think about how well they played? Or would you get a vibe from it?

What I’m saying is that Spirits has that vibe. I think it’s going to make it hard for anyone to say anything about how these instruments are played. The tablas aren’t even used as tablas sometimes; the sound has its own reason for existing, and it’s so truthful. It sounds like someone telling you their truth, whether it’s something you believe in or not.

I don’t know how it happened, except that I had sort of a nervous breakdown around that time. I decided to stop classical performances. It was a big deal; some strange stuff was going on with me. I just walked into the studio, picked up my flute, which I hadn’t touched for a long time, and started to play. Eventually I realized that something was going on. It was like praying. I decided that it was maybe not sinful to turn on the tape recorder at that point, because I wanted to hear the difference between what this sounded like and what it sounded like if I just decided I wanted to play the flute. As the days went by, it started becoming a major project for me, although I never considered releasing it.

Your approach to playing this music, even the fact that you would consider recording it to be a possibly sinful gesture, betrays a remarkably unusual attitude relative to how we hear pop music these days, with musicians and producers trying to exercise maximum control over their “product.”

My big question would be, “Who is the one who is in control?” If someone pointed him or her out to me, I would wonder, “What does this person know that allows them to get more music out of being in control of this than, let’s say, a couple of pygmy tribes in Central Africa, who are not even thinking of the word ‘control’ because they perhaps don’t even have that word in their language?”

Looking Inward

When you were just getting into playing the piano as a child, how much of what you were doing was based on hearing what other pianists had done on records and recognizing that as some standard to pursue — in other words, allowing that concept to control what you were doing? Or were you aware of a different way from the beginning?

No, I wasn’t aware of a different way. I had limited access. Ahmad Jamal was the most far-out of all the early people I heard. He had a white double-album that I really cherished, but that was partly because at that time I was playing the drums and it was a perfect album to play with. That was also a question of really liking that trio. Unfortunately, the guy I could get the most of around Allentown, Pennsylvania, was Andre Previn [laughs]. And a little Oscar Peterson.

“When I hear [classical pianists] now, whoever they are, it’s so hard to hear anything but their conditioning.”

What about classical pianists?

I never listened to them. I think that, without knowing it, I was doing exactly the right thing, because when I hear them now, whoever they are, it’s so hard to hear anything but their conditioning — how they were taught and what their teachers’ thoughts were. Then when I entered the classical world for those two years, I got into it pretty deeply. I met most of the people who were into things that I might have aspired to as a kid if I had been into that. Yet the overriding quality they gave off was frustration.

Because they were pursuing perfection?

Whatever. But I realized that you can’t be feeling the way these people feel and make music at the same time, because the openness that’s necessary to make the music is completely antagonistic to that frustration.

How do you cope with that when you play classical repertoire?

I select wisely the pieces that I have reason to want to play. See, that’s not the case with a classical player. If he only played the pieces he really liked, he’d be quickly out of work. And then he has to like them because he’s playing them. It’s a vicious circle.

In a sense, that puts you in an ideal position …

It does.

… because some percentage of the audience is going to come to hear Keith Jarrett play classical repertoire, whatever that repertoire might be.

That’s right. In fact, if I do any of those recitals again in the future, there will probably be no programs until the night the audience comes in. I wanted to do that in the beginning, but then I realized that it was a little too early to spring everything on everybody at once, so at least they should have a program.

New Paths to the Classics

In the business side of classical music, are you perceived as a serious artist or as kind of a carpetbagger from jazz?

The biggest thing is defensiveness. Of all the things that someone might expect to happen in a situation like this, that is the one that pops up most often. It’s like they don’t want to know how good it might be, because if it’s good on their terms, then they have to look at their own priorities again.

I even come up against that with conductors. It’s like, “Well, this will be over soon. He’s only one guest artist and I don’t want to get into anything too deeply with him, so we’ll just do a couple of rehearsals and it’ll all be over. The less we communicate, the better.” They can tell that if we’re going to be communicating, they’re going to be challenged somehow.

Do the musicians in the orchestras you play with have a similar attitude?

I’m afraid that often musicians are just doing their job. It’s like seeing somebody in an office saying, “I don’t want to deal with this new insurance policy.” In the Harrison piece, the first thing that happens is that the piano companies say, “What? A different tuning? Oh, no, we can’t allow you to use our piano.” The second thing is, when we’ve finally gone through all that, then the orchestra is supposed to tune to G and D instead of D and A. And they say, “What? A different tuning? Oh, we can’t, man.” Then we start rehearsing the piece and everyone is trying to put earplugs in their ears because they don’t like the sound. I mean, it’s worse than dealing with an audience. The audiences are probably more open than the orchestras.

Did those different tunings throw you off at first?

No. See, I had my harpsichord for about three years before this piece came out. I tune it to a not quite similar tuning. It has its own crazy intervals.

The classical repertoire you’ve played tends to resemble Glenn Gould’s preferences: pre-Romantic and contemporary works, with a large gap between them. Do you see similarities in the music of those two eras?

Yes, oh, yes. I mean, think of what the furniture looked like in the Romantic period! It’s so far away from the substance of the thing and so into the drama of the sheen of it. To me, drama in music should never be separate from some other purpose the music should have. If the music ends up being dramatic inside of its real purpose, that’s fine. But if it’s dramatic because we need something dramatic here after we have an adagio, then that’s not for me, with the exception of early in that time, like Mozart, where that was not so cut-and-dried and he was at liberty to choose whether he wanted to do that. You can hear in his music that that was not a pressure on him, that that was the way he heard things. That’s the way a symphony should be, so the music doesn’t come out as in the Romantic era, when we were saying gigantic things.

Are you interested in doing early repertoire on authentic instruments?

Yeah, I probably will do that sometime. In fact, I already did a clavichord recording for a Japanese documentary about an old Japanese drama. I used two clavichords together. It’s so Japanese, it’s amazing. The clavichord is more expressive than any keyboard instrument anyone has ever come up with.

Would you do a live clavichord performance through electronic amplification, so that a large audience could hear that expressiveness?

On certain occasions, I probably would.

You generally don’t play through amplification on the piano, though.

That’s right. I generally hate to see wires anywhere around. There have been times when they’ve left pickups in the piano and I have to say, “I’m sorry, but every time I look up I see these metal connectors and screws and bolts. You’re going to have to take this whole thing off.”

Your antipathy to electronics in music is well known. Do you also have philosophical problems with the electronic process involved in capturing acoustic music on tape?

Actually, I don’t have philosophical problems with any of it. It really is a physiological irritation, as if someone were smoking next to me. It isn’t as brain-related as it is total body, soul and brain. The sound of electronic music is what tells me what my opinions are about it, not something I decide to write to justify why I’m doing. When there is a purpose that I feel is warranted, then I can deal with anything that’s inside of that.

Like, I don’t smoke now and Manfred doesn’t smoke either. But there was a time when he and I only smoked at mixing sessions. We could have said, “We don’t smoke but this is when we do.” When the purpose was to get this one thing done, it didn’t matter what we had to do to get it done. If we needed to get stoned, we would have done it.

Do you prefer the relatively uncluttered act of live performance to working in the studio?

Ideally, I would prefer to be playing a tabla drum out in the woods. But if we get to studios versus live, I don’t have a preference, because they have separate modes. A live performance very often can’t produce as good a recording, for many, many emotional reasons. If I’m playing with a band that doesn’t understand that, then I’d rather be in a studio with them.

Music & Spirit

Recently you’ve spoken about what you see as a misperception of your solo piano recitals by people to experience them as ambient, meditative music. But isn’t it a valid use of music to help people get in touch with their environment in such a way that the main purpose of the music is not to be the center of listener attention, but rather to facilitate some other process?

You’re forgetting the fact that the best way to do that is without music. If somebody is going to get in touch with their environment, it has to be an organic environment. If it’s not an organic environment, then there is no relationship. It’s interesting that we think we live in a city when we’re in a city, but we can’t live in a city if what we walk on is not related to us. We do not live there; we’re trapped there.

Now, are you talking about new music that gets people close to something they’ve forgotten?

I’m talking about the difference between, on the one hand, sitting in a forest alone and getting a perspective on your relationship to the forest and, on the other hand, letting that process be facilitated by a good flute player who would be able to tune into what’s happening.

The better the flute player would be, the less inclined he would be to play the flute in the forest. When I say my ideal setting for what I would do would be to play tabla drums in the woods, that was a metaphor. I wouldn't actually go into the woods and play the tablas, because there would be no need for me to hear the tablas if I was in the woods.

The whole problem is that we now use a medium that has its own thing to do, to synthetically create maybe the desire to get close to something. And yet, that’s a synthetic desire, because either we’re doing it or we’re not doing it.

But music has been integral throughout human history to religious or self-discovery processes.

But, you see, there’s a difference. We’re living in a society now where we say we have the power of choice. If you belong to a church, you don’t have a choice. You go there and that music is part of the church you go to. That’s not the same. You’re saying that that’s parallel with someone deciding that he has to have some music on that can facilitate his spiritual growth, let’s say. But that assumes that the person who chooses to do that knows more than he possibly can at that time. How can he know whether he needs that music for that? Since he knows that he’s not where he wants to be, what can he need to do to get there?

“Life and consciousness within life can produce music, but music cannot make consciousness appear.”

In the case of churches, you have to assume that somebody decided that hymns are necessary for this church. You can’t, as a member of this church, say, “I’m sorry, but I’d like to leave during the hymns.” But that’s participation! That’s not exactly the same thing.

Well, would you concede that since this is a decision that each churchgoer must make for himself or herself, each of us might reach a different conclusion about what works in our own self-explorations?

Okay, but what I’m saying is this. Let’s take whoever that person is and take the music away. I think that person can get to wherever that is without it by going through a period of thinking that that’s the right thing for him, and then finding out it wasn’t … and what else is? See, the question is, what else will do it for you?

You’re also saying that if music is taken away from this person’s spiritual quest, then he or she will discover a greater dependence on the music in their spiritual process than they should have had.

If he realizes that. We have to assume that he didn’t realize that he didn’t need it to begin with. So the chances are not that great that he will realize when he finished that he didn’t need it. What he will realize is that that didn’t do it … but he won’t know what will: “Okay, that didn’t work. Or maybe it did. I’m in a haze.”

Maybe he should just go out and get some different music.

Well, that’s what they do. What I think I’m saying even more profoundly than all that stuff — and I don’t mean that in an egotistical way, I mean the center of it all — is that musicians who make the music that these people listen to, if their music is ever going to have the positive effect on anyone that we might able to make happen, have to be there [i.e., playing live]. And for them to be there is so unrealistic that a market has been developed for it instead. If there weren’t a market for it, if there were not a way to sell those records, if no one was interested in it, then you could find some music that would be appropriate for that.

Well, as a player, can you use your own music during a performance toward that end, for yourself or for your audience?

I believe that music does not influence music. Life and consciousness within life can produce music, but music cannot make consciousness appear. Music is next in line. In one level of transmission, I’d say that music is lower than consciousness. If someone has something ready to be reflected, music can strengthen that. If someone doesn’t, then that music has no part in their life.

So if we could tie that into your playing of written repertoire, that’s a part of you that you have ready to be reflected.

Yeah, that’s right. Let’s take Mozart as an example of someone whose music I never would have considered playing five years ago, not for technical reasons but because I hadn’t met him yet. When I could see who I thought I was dealing with, then I could play him.

When you play Mozart, do you perceive the piano as a different kind of an instrument than when you play improvisations?

Yeah, I do, but I appreciate the restrictions very much. I appreciate the fact that I’m now in a Mozart touch situation. I can get into that as if that was the whole world.

There’s a discipline that you have to submit yourself to when playing Mozart.

Yeah, but my feeling about discipline in music is far stricter than most people’s, although it wouldn’t seem to be, from what I do. My feeling is that if personal discipline doesn’t exist, and if personal realizations haven’t happened, then no matter what instrument you play, nothing is going to be music. If those realizations have happened, it’s impossible for you not to play music.

So if I finally meet Mozart, I can’t help myself but play Mozart fairly well, of course with limitations that I discover each time I play. Maybe those limitations should either become greater or less, like with the dynamics in Mozart. Some people think that he never gets to fortissimo, and other players play him much more aggressively.

Slings & Arrows

Do you worry much about authenticity in your performance, using terraced dynamics for Bach and so forth?

When you say “worry,” no, I don’t. But I enjoy knowing the story behind the music. I get into the ornaments and study that period and read C.P.E. Bach’s keyboard book.

That’s interesting, since John Rockwell, in a New York Times review of one of your concerts, singled out your execution of ornamentation for particular criticism.

No, actually, if we’re talking about the same review, he thought it was accidental that what I was playing was often authentic. I remember vividly because my representative in New York wanted to write him a letter, saying that it was a pretty off-the-wall assumption to make that Mr. Jarrett had not done his homework. The assumption he came with was that this was going to be a jazz pianist’s attempt at playing classical music. But, no, it’s a pianist’s commitment to playing the music, in the same way that any other pianist commits himself. Plus, I have a background in classical playing.

How much does the harpsichord influence your approach to playing Baroque music on piano?

I’m so strongly influenced by the harpsichord that I feel that only a few of Bach’s pieces should be played on piano at all.

Such as?

The French Suites.

What about the English Suites?

Not as easily convertible. Something gets lost. The Goldberg Variations I could see on either instrument, to some extent.

The Inventions?

Maybe on either instrument. But much of it only on harpsichord.

Are you thinking about playing more Baroque concerts?

Yes, but sometimes when I least expect it I’ve got another project going on that I had never even thought of.

Such as resurrecting your flutes and recorders for Spirits.

Yeah. And now I need a trumpet player, so … [Jarrett leans over, pats a trumpet case resting next to his chair and laughs].

###

Wow Robert, Ted Goia sent me / I love your conversation with Keith Jarrett / as a documentary filmmaker, I have a work in progress doc "Soul Searching" - "what's my relationship to music ?"

I really resonated with you r conversation with Jarrett and feel that you were able to get inside of him as much as anybody could and brought out something's that surprised me and probably him too / "a good talker is a better listener" and enjoyed your listening and follow up questions / at the bottom is a little back story on the Koln Concert you might enjoy too

as the other commenters below have their opinion / he's not for everyone / a friend of mine produced his Koln Concert, that almost didn't happen because he was frustrated at the German piano tuning and actually was about to cancel the concert and was in the limo and as she told me, she says to him (and I paraphrase) "it's ok it you leave and I will reimburse the audience and lose some money, but the people who come will be disappointed, and don't care about the piano they come because they love you and come for you" and the rest is history

Prickly. Huge influence. I panicked when I saw the headline.

I walked into a local record store chain in a Detroit suburb probably age 14. Looking through the jazz albums, haven't a clue. A cute employee asks if I need any help, I say I'd like to buy a jazz album. Could I be more specific? She says what instrument do I like? I say well I play piano concertos. She steers me to the Koln concert. I never looked back. Went to Columbia in part so I could hear as much live jazz as possible. Probably would have gone there anyway, Manhattan just blew me away. Probably would have stumbled onto buying jazz albums one way or another. Years later looking back you can say the staff was well-coached. Or not. Maybe I wasn't ready for Monk, or Cecil Taylor. The story of how the Koln concert came to be is fascinating in its own right, and should have taught Keith a huge lesson about going with the flow. But on some level, it didn't. Okay this is out of order and belongs a bit further down below.

Years later he's a big influence on my playing. A latent fear that my mind will go blank and the improvisation will hit a dead end, or I'll run out of ideas. But those left hand ostinatos . . . He ran out of ideas, that's why even in the Koln concert he'll repeat the same phrases measure after measure until something inspires him to change direction and explore that.

So getting back to the piano and that first album. What if I'd said synthesizer? Or organ? Maybe the employee steers me to Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, or Jimmy Smith. Different ice cream flavors, and I couldn't imagine always licking the same one. Duke Ellington with "there are 2 kinds of music, and good kind and the other kind."