Leon Russell

Musician Magazine (unpublished)

Even now, after fifty-three years, I think of that Leon Russell concert as one of the best I’ve ever seen. It was in a smallish venue – the same room, as I recall, where I had been taking some sort of music appreciation class – at the University of Texas at Austin. But when the house lights darkened and the stage spot flashed on, the air crackled as it never did for me during droning daytime lectures on Gesualdo or some other long-dead composer.

A second later Russell strode in from the wings. Not waiting for the cheers to die down, he went right to the piano, sat down and said, into the mic, “Let’s get it going right now,” or something like that. Truth is, if he had picked up on my appreciation teacher’s Gesualdo lecture, I wouldn’t have noticed, especially when he unleashed one of his familiar churchy arpeggios on the keys. Then he began singing, with those prairie-wide yowling vowels that harked back to his Oklahoma roots.

No special effects. Not even a band … yet. But he didn’t need them. The onetime anonymous studio musician was now a vital international superstar, buoyed by his success as music director of Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour, the unprecedented star power of the sideman gathered for his eponymous debut album, two subsequent hit albums, his high-profile appearance on George Harrison’s “Concert for Bangladesh,” and so on. For me, though, none of that compared to the experience of witnessing him in action. Overloaded with talent and charisma, Russell in 1972 seemed unstoppable.

(And, yes, when the Shelter People did line up behind him, I didn’t see hands shooting skyward or hear any glossolalia going on. But I did feel saved and purified by the experience. Still do, in fact.)

Exactly thirty years later, I knocked on the door of his unassuming home in Nashville. We’d set up an appointment to discuss his still distinctive piano sound, which we would illuminate in the “Private Lesson” section of Musician Magazine. His wife Janet swung the door open, smiling and welcoming my photographer and me. Russell stood behind her, not smiling, dressed down in sweats.

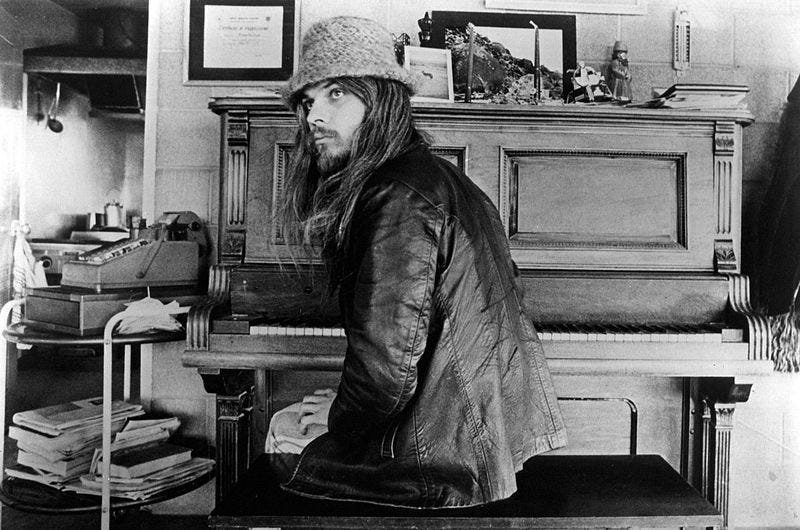

Truth is, Russell doesn’t seem to have ever been much of a smiler. In photos and from the stage, he conjured a look that seemed to hide restless energy and emotion behind an almost bored facade, kind of like the protagonist in one of his greatest songs, “This Masquerade.” By not breaking into fake grins before his fans, he seemed to me to be in control, taking his responsibilities seriously as a bandleader and entertainer, letting the music speak for itself.

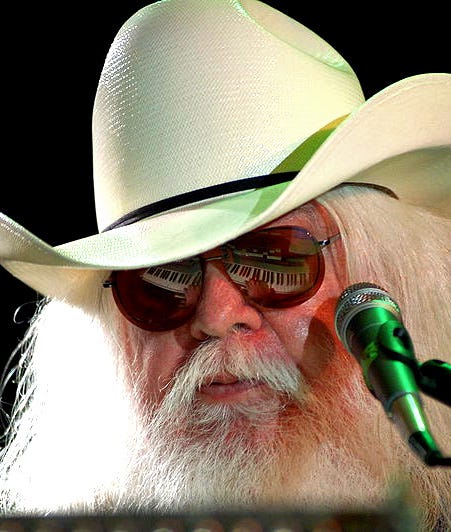

That sober look was there when we descended into Russell’s basement studio. It was small and crowded with equipment, with the conspicuous absence of any grand piano. There was, however, a therapeutic chair, into which Russell sank with a soft grunt. Throughout our conversation he manipulated its controls, constantly moving his seat cushion, back and foot rests, stopping only occasionally to pull at his ample white beard. He spoke softly, in a monotone, his expression stoic. Within a minute I knew I wouldn’t be able to get any “Private Lesson” material from him … but I did come to see this extraordinary individual quite differently than I had anticipated.

****

When did you realize that you’d developed your own sound as a piano player?

Well, I’m not really sure about that.

As you began learning to play, were you trying to conform to what your teachers were asking of you? Or even then did you resist being confined by expectations?

I had a birth injury that caused a paralysis on my right side. So when I was studying music, I had a great difficulty playing because of that. I had more luck inventing stuff I could play than I did playing other people’s written compositions.

What kind of paralysis was it?

They falled it “spastic paralysis.” I believe they call it “cerebral palsy” today. There’s a birth injury to the upper spine, and it caused a paralysis on the whole right side of my body.

Is it in remission now?

[Quietly.] It’s always there.

And that made it hard for you to play certain parts in the music you studied.

It was impossible. I studied for ten years, and finally I just quit because I couldn’t play that stuff. I saw people who had been taking lessons for three years play circles around me when it came to playing classical.So I got very disappointed and I stopped taking lessons for two or three years. Then one of my piano teachers took me to a concert of a one-handed classical piano player – his name was Mackie, I believe. I was impressed by that. I thought, “Well, even though it isn’t a real hand, at least I had two levels [unintelligible]. It was inspirational to see that.

Did you start playing trumpet in part because of your hand problems?

No, that’s just the kind of music they had in school. I lived in a small town in Oklahoma, and in the fourth grade I was in the high school band, playing baritone horn.In fourth, fifth and sixth grades, I went to grade school all day but then I went over to the high school for band. It was an award-winning band, with a great teacher. Then when I was in seventh grade, we moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where the junior high band was awful. I stayed there for three years, hoping to get to the high school band. Then when I got to the high school band, it was awful too. It was a very big part of my life, that band stuff. I loved it. But that band in Tulsa was hideous.

Did that experience lead you to take up the piano again?

I never left the piano. I started playing nightclubs when I was fourteen.

Can you go into a little more detail about how the palsy impaired your technique and how you adapted to that?

There was muscular paralysis, so I couldn’t play exactly what it is [sic]. It took me a year just to be able to comfortably hold a guitar pick. New movements are very difficult. I had to invent ways to play that I could play, and in doing that I did whatever it is.

Well, you came up with something that works, since your playing never sounded limited to me.

It’s an illusion. That’s the point. I try to make the illusion. I got into trouble playing sessions in California. One time this guy named Stu Phillips was there, a conductor from New York. He came out to hear me play on a record date. He said, “You’re the guy I need. I’m doing a Beatles album tomorrow in the style of Chopin, and I haven’t found anybody who can play. You’re the guy!” “Well,” I said, “I gotta tell you. I don’t read that good. And what I’m doing is an illusion. I can allude to classical music, but specifically I can’t play any concertos and I can’t read very complicated at all.” He said, “Oh, you can play this. I heard you!” So I went over there the next day. I said, “Stu, I’m sorry, but I told you, I can’t read that. That’s way beyond what I can comprehend in my mind to look at. I can’t hear it in my mind.” I told him who to get, but he wouldn’t believe me. He thought I was being modest or something. And I’m not falsely modest; I was just trying to help him.

So what happened?

Well, he ended up trying to play it himself. And it was terrible. I guess he brought somebody in. He wasn’t expecting to play it; he was just arranging it.

Surviving the Classics

A lot of players who come from classical training find it hard to develop an original voice beyond the conventions of their training. You, on the other hand, learned from that tradition without succumbing to it. What composers do you like?

Well, I studied all of ‘em. Beethoven, Chopin … it’s been a long time, but I was exposed to all that. I had a great piano teacher in Tulsa. She was a great player, and I got to watch her play, which was very important.

Did she help you with the muscle problem?

It’s not a very obvious ailment. I just have a lot of problems with certain things, like scales.

So if you had to play some sort of a rising single line with your right hand, you figured out how to create an impression of that line rather than do it literally.

They call it “shtick.” I developed different things for those occasions.

Was it just alternative fingering?

There were arpeggios I played with both hands. I played with both hands.

Like this? [I illustrate a hand-over-hand movement.]

Yeah.

Alternating octaves were also a signature of yours.

That’s [from] Edvard Grieg. It all came from him.

Were octaves physically difficult?

I worked real hard on certain things because I didn’t have other things. That’s one of the things I worked hard on; I felt that they worked as a melodic tool. I used to practice lines and octaves in both hands.

Simultaneously as well as alternately?

Both, yeah.

You did this in all keys?

I tried to be aware of it.

You also drew a lot from church music, which added a lot of emotion to your playing.

Well, I endeavored to play harmonica solos in my right hand on the piano, because harmonica has certain built-in limitations. You have to have an overview of some kind to make that thing work, because not all the notes are there and there’s just a few acceptable licks in that bag. You’ve got to know how to put all that stuff together. So I started playing that on the piano as a piano style. I think somebody could make a lot of money doing that on saxophone too.

Did you play harmonica?

Actually, I never could get it. I listened to a lot of it, especially the bending of the notes.

Floyd Cramer did that same thing in country music.

That FLoyd Cramer feel is different; it’s based on steel guitar. Of course, you can’t bend those notes on a piano. You have to do it with grace notes. It’s a different set of licks. He was playing pedal steel licks, like if he was playing a C and a G, then he would play from the G to the A. Blues is different.

When you were still in your mid-teens, you were already working gigs around Oklahoma with Jerry Lee Lewis. How did that happen?

There’s a place in Tulsa, my home town, called Cain’s Ballroom, a big country and western place. Jerry Lee was doing a show there. Thisas in that period of time when he married his cousin and got run out of England, so he was kind of at the bottom of the heap and he wasn’t carrying a band. So somebody hired my band to back him up. I played for the [sounds like: dancement?]. Then when he came on the stage, I got up and he played. I had studied his style in particular. I noticed, for one thing, that Russell Smith, the drummer, played a shuffle while Jerry Lee was playing a straight beat, all the time.

Who was his bass player?

That was J. W. Brown. He had only one lick. He’d play [Russell sings a quarter-note walking pattern of C-A, G-A, C-A, G-A, et.] He played that on every song. My guys, never having played with Jerry Lee, knew all that stuff. We knew all of his songs and all the keys; the drummer knew how to play it just like Russell Smith, and the bass player just like J. W. And I just sang his song. So we got up there, and it was fun to watch. He had been playing with a bunch of pickup bands. Nobody knew anything. He got up there and started out. Well, they just started right in with him. I always had ‘em trained to start together after two bars ..

A piano intro?

Yeah. If somebody misses it, then you gotta wait until the next two bars. But they just came right in and plagued it. He just kind of looked around, he sang the song, then he did the next song and the next song. Then he started trying to play songs that he hadn’t recorded that I’ve never heard him play … but I’d also taught my band how to play songs they didn’t know. It is possible to do that, just by looking at those events so you could follow it. So they played all those songs. He hired us on the spot after that show. I was on the road with him for a couple of years.

What did you do while he was playing the piano?

I didn’t play. I played the opening show, then I got up. Sometimes when he’d get up at the end of the show and walk around the stage, he’d call me up and I’d play.

A lot of bands don’t understand how to combine straight and shuffle rhythms to get that particular groove.

Well, Charlie Watts and Bill Wyman [drummer and bassist with the Rolling Stones] always had this interesting thing where Bill played way on top of the beat and Charlie played way behind. They just went along like that all the time. That’s one of the things that made their rhythm section sound like that.

The West Coast Sessions

You eventually moved to L.A. to do session work. How did you conform to the kinds of sounds they needed from the pianist on, say, Frank Sinatra dates?

Well, on the Sinatra records, I played triplets. This was when [producer] Jimmy Bowen was cuttin’ all those triplet records with all those stars, and I was the guy who played the triplets. I figured out early in the game when I got out there in California that if you’re gonna hear the piano, you had to play it up in the high register. So I always endeavored to play up high, and they noticed that. They could hear the piano, where most of the other pianists they couldn’t hear it at all. So they thought I was doing something.

What’s the secret to playing triplets with the correct feel?

Well, today you can put it on a computer and see what’s wrong with it. Most people’s timing was just all over the place. And I come from rock & roll and ballads, so that [unintelligible] was my type of music.

If you listen to, like, old Fats Domino stuff, there was an unmistakable subtlety to how he phrased his triplets.

It takes practice. It’s just like playing with a click: If you don’t do it every day, you’re way off. But if you get a computer and a sequencer, you can check it and see what you’re doing wrong.

What was it like to play piano on Phil Spector sessions?

It was an amazing band. Jack Nietzche did the arrangements. When I started doing those records, Jack used to write some stuff. It didn’t seem to me that Phil ever used any of it; he did it all off the top of his head. S then Jack just got to where he wrote chord charts. It was a small studio, with three pianos, five guitars, five horns, sometimes a couple of drums.The first run-through always sounded great.

Who were the other pianists?

It was always Al De Lori and Don Randi.

Did all three of you guys play identical parts?

Different parts. I always did the high stuff on those records because, like I said, it sticks.

What was it like to find your place among the L.A. studio players?

It was just who you know. I started playing demos at Metric Music, me and David Gates [later known as leader of the group Bread, who first played with Russell while both in Tulsa’s Will Rogers High School], Glen Campbell and some other guys. We played these demos for Jackie De Shannon that Sharon Sheeley wrote for Metric Music. Jackie was having a showcase down at the Band Boxor somewhere, and she asked me to come and play. Jack Nietzche was down there and heard me play, so I started doing quite a bit of the stuff that he was doing. That’s how I got on the Phil Spector stuff but also Terry Melcher, a lot of Columbia stuff and so on. I started doing sessions when I was twenty-one after being out there for a few years. At the age of seventeen I was unable to work without borrowin’ I.D.s. I was a member of the Union, but the Union was terrible with its members, I’m sorry to say. But the weekend I was twenty-one I got my first session, and every week after that they doubled, like two the next week, then four the week after that, then eight, then sixteen. It was just, bang, I was working a lot.

“I used to work for these arrangers who … let me play whatever I wanted.”

“I used to work for these arrangers who … let me play whatever I wanted.”

When you started doing your solo albums, you had already developed a highly personal sound on the piano. This must have reflected your distinctive personality as a musician more than the dates you’d been playing on the West Coast.

Yeah, but remember, they usually hired me for what I played. I used to work for these arrangers who wrote volumes of parts for the other musicians, and they only wrote chord sheets for me and let me play whatever I wanted.

That was a real compliment to you.

Well, it worked out for me because that’s just about the only way I could have done it. I’d run into people who’d hear me play and say, “I gotta get you to do this for me.” I had this one jazz singer – Mel Tormé, I think it was – listen to all my licks. He wrote ‘em all down in an arrangement and he wanted me to play ‘em all on Hammond organ. I told him, “I’m not an organ player. I don’t read that well, Sorry. Get Lincoln Mayorga.”

Life After Pianos

Bruce Hornsby told me a while ago that you’re no longer playing acoustic piano.

That’s right. I stopped about seven years ago.

Why?

If you move ‘em, you gotta tune ‘em. And my touch is very light. I found about one piano in thirty that had an action I liked. Then whether it sounded good on top of that was another problem. What I use on the road is so much easier to handle.

What are you using on tour?

Four modules, just for the grand piano. I don’t really care to tell anybody what they are. Anybody could make a great piano sound with what’s available on the market. It’s getting better all the time.

Did you check out a lot of options before you settled on those modules?

Of course. We use the stuff in the studio all the time, so we were always looking at the sounds and trying to come up with a good representation for what we’re trying to do. The deal on the road setup is that you’ve got to move it every day. I had originally set up in eight sixteen-space road boxes, with big military plugs, and it was breaking all the time. So I consolidated it into one case: The plate comes off [and] it becomes a riser. I sit on that. The keyboard is there, the mixer is there, the teleprompter is there, all the power amps are there. You plug the speakers in and turn it on. It’s a lot better than it was before.

Would you ever go back to playing piano in a studio context, where you don’t have to worry about moving the instrument or keeping it in tune?

No, I wouldn't. In fact, I am playing real pianos now; it’s just that they’re hand-picked out of thousands [of sampled sounds]. See, in the early days, when I was playing rock & roll, my hands would bleed. I was spraying blood all over people’s white jackets because it was never loud enough. It was hard to amplify. This way, it’s not microphonic. There’s no feedback potential at all, so I can be as loud as a metal player.

####

I saw Leon play at the Cain' Ballroom, & saw him play at his birthday party, at the Brady Theater in Tulsa. There will never be another Leon.

One of the best interviews I've read! Filled in the blanks in my thirst to know about Leon Russell's style and career. Wow. The man was everywhere when things were happening.