There are two keys to pitching story ideas to editors: timing and concept.

So when I read a press release announcing a collaboration between smooth jazzer George Benson and R&B legend Little Anthony, I sensed a perfect convergence. Quick research determined that Anthony, born Jerome Gourdine, had apparently never done an interview on the subject of jazz and its importance in his life. This seemed odd to me, as he had grown up in Brooklyn during the peak years of the jazz club scene across the East River in Manhattan. Also, I’d never seen an interview with Anthony or any other R&B vocalist of the “doo-wop” era that focused on their jazz influences, which to me seemed evident among the best of them.

Luckily DownBeat approved my pitch, so I devoted some time to studying Anthony, with specific attention to his awareness of his great jazz contemporaries. My explorations were like a stroll through an especially bountiful orchard, whose fruits other writers had somehow passed without taking note.

Anthony’s path through R&B history is much better and more frequently charted. He started singing as a child with local groups back in the Fifties. The Imperials themselves came together in 1958; right after that they scored their first hit with “Tears on My Pillow,” followed two years later with “Shimmy, Shimmy, Ko Ko Bop.” After a brief departure to attempt a solo career, Anthony returned to pilot the group to a new style, heavy on drama and emotion, shimmering with Teddy Randazzo’s orchestrations. Their list resumed with “I’m On the Outside (Looking In)”and “Goin’ Out of My Head” in 1964, “Hurt So Bad,” “I Miss You So” and “Take Me Back” in 1965 and “Hurt” in ‘66.

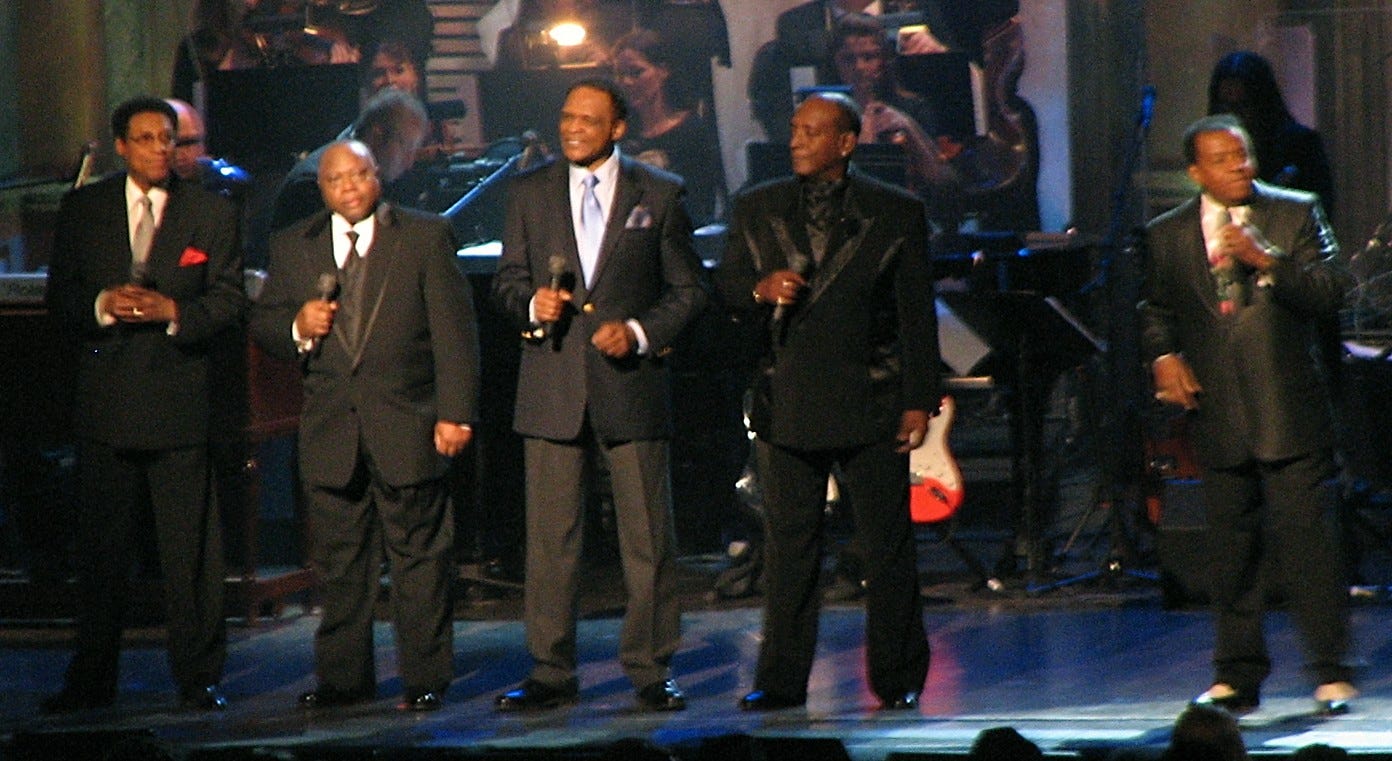

Little Anthony & the Imperials rode the crest of their success onto multiple TV shows, including pop stardom’s non plus ultra, The Ed Sullivan Show. Time inevitably nudged them from the mountaintop and precipitated a flurry of lineup changes, but Anthony never left their spotlight as they soldiered through casino gigs and oldies tours and eventually to Cleveland, Ohio, for their induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2009.

Anthony and I met in the Music Row office of publicist Kirt Webster. The first half of our interview was devoted to his collaboration with Benson. I’ve trimmed this section down to make sure this transcript maintains an overall broader perspective on his life in, or actually in the vicinity of, jazz.

****

Have you known George Benson for a long time?

A very long time! I knew him when he was a young dude out of Pittsburgh. We got a bump in each other [?]. George became an admirer of me as far as the way I sang. He would say “I do the best impression of you.” He’d like to think that [laughs]. But then I was blown out by what he was doing. I realized what a technician is as a guitarist. He had great chops — he still does. It was a mutual admiration kind of thing.

Very rarely do you find a great player who can also sing really well.

This guy has been playing his guitar since he was a little boy. He told me he would listen to all the things that kids did in those days — rock ’n’ roll. The way he was taught and trained was to do jazz. I don’t know what influenced him because Herbie Hancock took a lot of flack when he went to another direction. He wasn’t totally bebop. Everybody said, “You’re a sellout!” That’s when George started to click. Man, that was the late Sixties going on the Seventies and right in the Eighties. I’m listening to the radio and here he is — and he’s hot! He’s on fire!

He put out hit records but his solos weren’t dumbed down.

He won a lot of awards. We were just talking and I said, “Every time I hear you? Wes Montgomery, man!” And he said, “Oh, yeah!” That was his influence. When Wes passed, he just kept doping it. It became a part of him. And he incorporated his voice with playing that guitar. If you listen to Errol Garner’s records, you hear him humming. And Oscar Peterson! It showed you where their minds were going. When he was working with Quincy [Jones, producer], he said, “Man, I started doing that thing. Everybody said, ‘That’s cool! Keep that in!’”

Was this the first time you’d made music with him?

It was the first time. He always said, over the years, “Man, I’d love to do something with you because you are my idol!” I said, “Come on, man [laughs].” That’s how that was, as simple as that. When we would run into each other, we’d always say something like that: “We should do something.” But we weren’t thinking anything would happen.

Then I had just signed to Mr. David Ross of Reviver Records. I said, “You know, I got a call from George the other day.” Mr. Ross said to me, “You know him that well?” I said, “Yeah! I’ll give him a call.” So I called him. I said, “Dude, have you signed to anybody? Because I’ve got a little something going here. They’re doing singles, developing the album.” David Ross wanted to do all duets but I don’t do duets. So we sort of compromised because I saw something a little bit different out there. I figured we’re not in today’s music as older artists. The way the industry is set up, they don’t want any older artists to do anything new. I don’t understand that. They’re different from Europe and Asia and South America. I love my country but we are a capitalistic country to the bone. We’ll take down a work of art to put up a parking lot if it makes some money. The artistic part of it right now is for the old artists, like George, Smokey [Robinson] and myself. I wouldn’t call it a challenge. It’s what we do. We can’t stop what we do.

So a wonderful thing happened: social media. It’s a different ballgame. If we self-promote us, we can actually go through. And then iTunes came in and Amazon picked up on it. Now we’ve got this whole new subculture that actually shook up the recording business to the point where record companies were closing down! You remember Tower Records all over the place? You ask a young kid today if he remembers Tower Records.

Or even if he remembers records!

What’s a record [laughs]!

***

Bebop in Brooklyn

Was jazz important to you as you grew up?

Oh, yeah. I knew Mr. Teddy Regal at Blue Note Records. It’s in my book [Little Anthony: My Journey, My Destiny]. My dad was a jazz musician. Mom was a gospel singer. All of my aunts were gospel singers. My dad used to play with big bands. He played with Buddy Johnson’s Orchestra and quite a few people. He used to drag me around to the Savoy. I met Duke Ellington. Later on I met Count Basie. The music in the house was going all the time, those 78 records with the little holes in the middle.

One day my dad played this thing by Illinois Jacquet. He was hitting some stuff on the alto sax; even as a kid, I was going, “What is that?” I got totally fascinated. The next thing I know, I was listening to Dizzy Gillespie, who I got to meet — and Quincy Jones. I started hanging out with a bevy of people in jazz. In New York they had a club called the Village Gate. Everybody was there. I went there and saw Thelonious Monk. And I saw John Coltrane. That was the experience of experiences. Alice Coltrane played piano. Man, she could play!

How old were you then?

I was seventeen, sixteen or eighteen. I was sneaking into the Village Gate. Nobody was asking me any questions.

And you were doing vocal gigs then too.

Yeah. It was me, one of the Imperials Clarence [Collins], and Kenny Seymour, another Imperial who was really a jazz aficionado. He started pumping: “Man, we got to check this out.” The place to go at that time was the Village Gate. So I got to see Mongo Sanatamaria …

What about Miles Davis?

Miles I knew very well. [In the famous Miles rasp]: “You got my voice, man [laughs].” Miles was deep very deep. But he was cool with us. It was [sounds like: Devil Morgan or Warren] who introduced me to him.

“‘Doo-wop’ … was just a label that was put on us because people didn’t understand what we were doing.”

You were singing R&B and doo-wop, but did jazz influence how you presented the melody, how you phrased and so on?

Yeah. When people have a tendency to lump people in the same bag, a lot of times it’s not derogatory but it’s just a fact of not knowing. First of all, it wasn’t doo-wop. There was no such thing as doo-wop then. That was a figment of the imagination of a disc jockey in New York in 1973 when he was trying to explain to his audience what kind of music was. I get very adamant when they start saying doo-wop because that was just a label that was put on us because people didn’t understand what we were doing. The groups in those days were black or white. Most of the white groups came out of New York City. Black groups came out of Chicago, Philadelphia and mostly New York City. We had a style. There was a dance called the Grind and all that kind of stuff. The white cats could not emulate it. They just couldn’t do it vocally. Then they began to develop their own style, like Dion. [He sings, “Where Are You, Little Star?”] And they had some songs with “doo-woppa-doo-woppa.” We were able to do crazy stuff. Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers? Sherman Gaines was one of the finest bass singers I’ve ever heard. People don’t realize how good he was. He would sing, “oo-poppa-cow-poppa-cow, oom-moppa-doo-moppa-doo.” The black groups — the Flamingos, the El Diablos, the Moonglows, the Orioles — we were doing R&B. It was just R&B. It was called race music.

It had beautiful harmonies, though not tight like the Hi-Los …

It was raw!

So part of the gig was you could phrase within the melody but you couldn’t improvise much.

Only the lead singer could, the front man. But the structure of the singers in back of you was basic. Look, Kenny Seymour turned me on to the Four Freshmen, with four-part modern harmony. We started doing it and it blew people out of the water. But if you can sing, all you need is instruction. Kenny was a pianist, so he would just pick out the notes on the piano: “Okay, you do this.” He understood musically how that works and he started teaching us. So we were into the Freshmen, the Hi-Los … I was heavy into the Hi-Los because that tenor, man, when I hear him it still blows my mind how good he was. But I can speak for those of us who are not here anymore and say we all were lovers of jazz. If you listen to what we were doing, there was some jazz influence.

One jazz vocalist, Jimmy Scott, is often listed as one of your main influences.

Jimmy Scott was my big brother! We talked all the time. He lived in Vegas but he’s passed on. Honey [i.e., Scott] advised me because of my high voice. When I spoke with Nancy Wilson, she told me that Jimmy influenced her. Well, Jimmy influenced Frankie Lymon of Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers. We were all trying to do what he was doing. One thing he was doing, he was able to hold his notes without vibrato. When Nancy picked it up, a lot of us were like, “That’s kind of interesting. How do you do that?” He was such a musical technician with his voice that when he needed to, he would go in. Now, if you listen to Stevie Wonder, he’s influenced by Jimmy Scott! Frank Sinatra said he was influenced by Jimmy Scott.

People also mention Nat Cole as someone who influenced you.

Nat’s diction, his enunciations, were so perfect. Not that he was a great bebop sort of guy; he was kind of old-school. If you listen to him from when he was younger, he grew and found a groove. One of the people that began to understand that was Nelson Riddle. Nat introduced Sinatra to Nelson Riddle! I never met Mr. Nat Cole but I met his ex-road manager, who told me all kinds of stories about it. He used to say, “I wish he didn’t smoke so much.” I met his daughters. I met Natalie, who just passed away. I used to tell her, “I always wanted to meet your dad. It just didn’t work out.” She said, “No, you didn’t meet my dad — but my sisters love you [laughs]!”

Tell me what these people meant to you, beginning with Sammy Davis Jr.

I had the great pleasure of becoming his friend. I used to hang out in his suites. If anybody taught me about this business, it was him. It was manifested in life that we would come together. He used to hold court and he said to me, “Hey, man …” You know, when Sammy was with the brothers, he was a brother. He said, “Man, you cats got those hit records? I don’t have nothin’! I had to come up …” And he’s telling us all the pain and sorrow, and the violins are playing. And he said, “You had all those hit records and I had one! ‘Candy Man’!” He thought it was stupid, like “Shimmy Shimmy Koko Bop,” which we did. But it was the biggest thing he ever had. But prior to that, he said, “It was everything I had as a talent to develop and getting recognized as one of the greats. You guys got hit records. So why are you crying to me [laughs]?” But he saw us perform and he liked what we did because we were old-school.

How did you meet Sammy?

I met him through a couple of people. Skip Trenier and the Treniers, he was very close to them. His [i.e., Davis’s] wife Altovise, her real name was Joanie Gore. She’s from Brooklyn. We used to live in Fort Greene Projects and she used to go to dance school. I get invited by this famous actor: “Do you want to see Sammy in Golden Boy?’” I said, “Really? Let’s go, man.” That’s where I saw Altovise; she was dancing in the chorus. Then I go backstage and, boom, that was the first time I looked at Sammy Davis. He was like this height. I gotta show this, man. [Anthony perfectly mimics Sammy’s hipster walk.] “Hey, babe.”

“As performers, we’re like shooting stars.”

You wrote with Sam Cooke.

Any experience as performing artists, we’re like shooting stars. Each one leaves their legacy. So Sam gave us a lot. He was one of the first blacks to understand the show business. He was developing his own record company. He was bringing people on. I knew Sam when he was with the Soul Stirrers. See, my mother would take me around. In those days, it was very difficult for blacks here in New York to go downtown and get a hotel. So they had what they called “guest houses” up in Harlem. My aunt Sarah, he would come up there. That’s where I met him. He called my Aunt Sarah “Mrs. Ford.” Sam was six years older than me, I think. Because Aunt Sarah was looking at him like, “Boy, he’s a man!” He was knocking down the ladies even in the gospel! That dude was strictly handsome!

After he became this huge pop star, he went back and performed a guest vocal with the Soul Stirrers — and the audience was silent.

It’s in my book. It was 1959. We were at the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C. I remember some of the people on that show: Sarah [sounds like: McLutton] and these two young guys called Sam and Dave who were just starting out. Nobody knew who they were. They opened the show. Sam Cooke was on there and the great dancer Bunny Briggs. That’s vaudeville, man, that’s what it was: the chitlin’ circuit. We were young kids, eighteen or nineteen years old. We were just taking this all in and yet we’re on the show. We started talking with Sam and I told him, “I used to see you when you were coming to my aunt.” He said, “Oh, Mrs. Ford!” That started our relationship.

The guys — Tracy, all of us — loved gospel. We used to sing it backstage, like Elvis. A lot of them were the Soul Stirrers’ tunes: “If I Could Touch the Hem of His Garment.” So we would feel around and … I can’t remember his main man. Was that his manager? I can see his name but I can’t get it out. He said, “Hey, man, why don’t you guys sing gospel for a while?” Jackie Wilson, all of us did. So Sam came and said, “Do you know the background of the gospel thing we did? It’s called ‘Wonderful.’” It’s like jazz but that’s more improvised off the melody. The tenor is prominent. So he said, “I’m gonna do this in the show. You guys can back me.” We didn’t go on the stage with him, but we had an open mic backstage in the wings. We rehearsed a few times in the dressing room and we actually did it. That was a highlight of my life — singing this gospel thing with Sam Cooke.

He liked me. One time we actually shared a dressing room. We shared a lot of things together [laughs]. It’s in the book.

Thinking About Jazz

Did you ever actually sing a jazz gig?

I never sang with a jazz band but I can sing jazz. I thought about it. Moments ago, I just got a call from a great Latin player; his name is Joe Bataan. He came out of the Tito Puente era. That’s another part of who we are — salsa — because you don’t come up from New York and not be …

It wasn’t called salsa back then.

No, it was called mambo. He asked if we could do some things together with a Latin flavor. I said, “That sounds good to me.” So we were talking. I would like very much to do something jazz. One of my influences was Ella Fitzgerald. I got to meet her too — that was great. I knew her husband, Ray Brown. He played on “Going Out of My Head.” And he knew my background and my love of jazz. So he talked to me and I was sitting there, listening to Ella. And I said, “Hey, man, she’s an instrument.” I didn’t know until one day they did something on her and said, “That’s what she discovered after she got the Chick Webb orchestra.” She loved to hear the bass and all the things that would go on with the musicians. So she became a horn when she would do that scat stuff. She influenced the rest of the ladies that were coming up. Miss Sarah Vaughan? Now, Sarah came straight out of the church. She had her own style. I got to meet Dinah Washington, who to me was one of the great technicians you’d ever want to hear. But that all came out of Ella. We really intertwined.

I’ve tried to explain that in several interviews. First you had gospel music or spiritual music. That gave birth to the blues. Blues gave birth to jazz. Jazz gave birth to rhythm and blues. Rhythm and blues gave birth to rock & roll, and on and on — no doo-wop in there. So there is a familiarity of all these singers.

We’ve talked about singers who influenced you and about keeping your voice strong. What are your thoughts about the qualities Billie Holiday showed as a great singer even after her voice began to deteriorate?

Well, again, she was a miracle technician. We all know about what she was going through. I never met her. I wish I did. I would have picked her brain. But I sure listened to everything she did.

If you and I had a duo gig, what jazz tunes might you call?

That’s a good question. I don't know. There’s so many of them. I’d probably lean on stuff that Jimmy Scott did because I feel closer to his technical voice. I’d probably go his route. I did it fooling around like everyone else, in the shower. But I know in my heart I could do that.

Betty Carter and I just did a gig together, a benefit with Manhattan Transfer. The late Tim Hauser was a dear friend of mine. He was singing street music — R&B — but he went in the jazz direction. All those cats started out a certain way in that era and then they found their little niche. There was a book written that explains who we were: They Sang Under the Streetlight [no such title on Amazon]. It really did nail what it really was.

“My voice is not natural. It’s supernatural.”

How do you keep your voice in shape?

My voice is not natural. It’s supernatural. There’s no way that I can sing like that at almost 75. I spoke to Tony Bennett about that same thing and he said, “I don’t know how it works.” And he’s 85 or 86? And Mel Tormé, man, he scared everybody. In 1973, this throat doctor, Charles Schneider — it’s in the book — I was doing two-and-a-half packs a day. I picked that habit up when I was a kid. And I started to have all kinds of trouble. I started getting really scared. I was getting ready to move to California when a man by the name of Dr. Roger Rose, who I met in New York City — he was Babe Ruth’s doctor — said, “I’m gonna hip you to a cat who’s one of the top. He works with Johnny Mathis and all these great singers.” When I finally got to Dr. Schneider, he said, “I’m gonna teach you something, man. First of all, you’ve got some nodes on your vocal cords. We can treat that because it’s not as bad; we don’t have to go in. But I don’t want you to keep doing this because eventually we’ll have to go in and take them out — and that’s hit-and-miss. A person could lose their voice totally when you’re messing with vocal cords. The second thing is, you’ve got to give up cigarettes.” I said, “What?!” So he made an appointment for me to go to a new company called Schick [tied to Schick Shadel Hospital, based on aversion therapy] that was dealing with addictions. That was the greatest thing I ever did when I went there. I never smoked again.

The third thing he said to me was, “I can tell from the way you’re talking that you’re not using your … [he points to his stomach].” This is where everything happens. Before, I was a throat singer. Most people who aren’t trained are throat singers. Opera singers are diaphragm singers. And my voice was supernatural. It’s something I can’t explain but it’s also those things that I learned.

When you’re singing from your stomach, that’s also somehow more emotional than when you’re singing from your throat or your chest.

Nancy Wilson understood what it was to sing from here. She really learned that stuff. I learned from a doctor. I never did learn from a singing teacher. The doctor taught me exercises. He said, “I want you to do these exercises every day for five or ten minutes. Don’t think about it — just do it.” So I did it for a year. Before I knew it, my solar plexus in here was like a rock. He said, “Unconsciously, you’re going to begin to sing that way if you keep with these exercises. I’ve done that with many artists.” He was one of the best throat doctors out there.

Once More, With Feeling

On many of your biggest hits, the lyrics explode with emotion. How do you get into a lyric, find the feeling and find how to let it loose?

Sinatra made this statement. He said, “Never try to do a song if you can’t do it comparable or better, don’t do it.” Sinatra was the master of lyrics. So was Nat Cole. So I was influenced to listen to Nat Cole through a man by the name of George Gouldner, who was the president of End Records in 1958. He had me listen and listen. By listening, I picked up the technique. In the book I tell about how Little Anthony became Little Anthony — that sound. It really was Mr. Gouldner. We were in the recording studio, doing “Tears on My Pillow.” It was the fourth or fifth take. He said, “Anthony” — he was telling me from the booth — “Why don’t you sing like you talk?” He said to me, “Who’s your favorite singer?” I said, “Well, I love Nat Cole a lot and Frankie Lymon.” He said, “The way Nat Cole sings, the way he enunciates everything perfectly? I want you to try that.” So I thought for a second and said okay. And that’s where [he sings in clipped articulation in high register] “You don’t remember me but I remember you.” That was when I became me.

Sinatra was the greatest technician with lyrics. I learned a lot from him. He took every note and personalized it. Why? Well, look at the life that he lived. When I came off the streets, I was associated with Teddy Randazzo and all the experiences with a lady he loved very much. If you listen to “I’m On the Outside Looking In,” “I’m Going Out of My Head,” “It Hurts So Bad,” he was going through a really rough time, so he was expressing it. Teddy told me, “Man, you’re gonna be my voice.” He didn’t instruct me. I just knew the pain he was going through because personally I knew him all these years. So when I began the singing, Mr. Don Costa, who produced it, was in the booth, looking down at me — all the musicians were in the room in those days. When I sang, “Well, I think I’m going out of my head,” because I knew what Teddy was going through. So it transformed into me and my emotions got involved: “Oh, that poor guy!” And it came out of my voice. Ninety percent of the good artists do it.

Teddy was a big influence on Burt Bacharach.

Oh, he was. And he got his stuff from Don Costa, if you listen to their arrangements, because he used French horns a lot and I use a lot of French horns. In 1967 or ’68 we got a call from the William Morris Agency. They said, “Hey, they’re having a big concert with Dionne Warwick and we’re going to do it at Lincoln Center with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. Burt Bacharach would like you to come as a guest.” And he invited Teddy. Can you imagine singing with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra? It was the greatest night of my life. It was all black-tie. John Lindsey was the mayor then.

Who conducted the orchestra?

Teddy conducted for us. We opened and the audience stood up because when you have that kind of sound, all those violins, it was very impressive, even with me: I’m onstage and I’m getting really emotional, man!

####

What a delightful and fantastic article. I’m reading this on my lunch break and I’ve taken just about every of my 30 minutes to score this remarkable read. Thank you so much!

This made decide to dive back into some of that great 50s vocal group music again. It's been too long!!