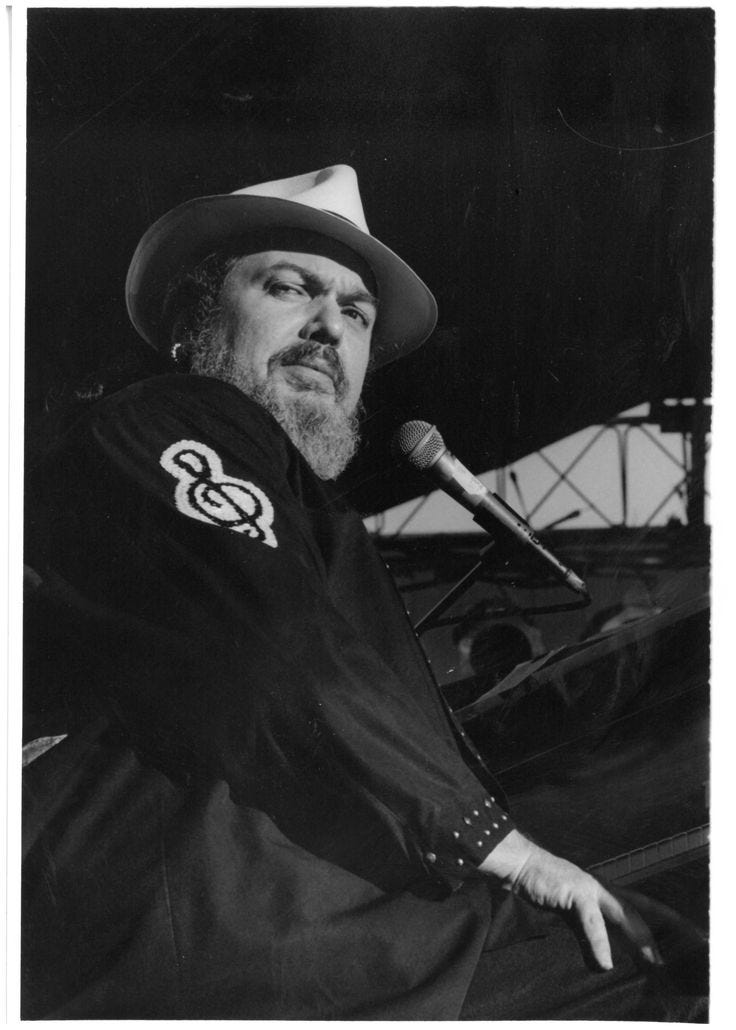

I mentioned in the first part of this transcript, posted here on June 24, that Mac Rebennack, a.k.a. Dr. John, looked weary when we met for our interview in Seattle. Not “tired” but “weary”: worn by crisis after crisis, the most recent including his daughter Jessica’s unsolved murder and Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of his beloved New Orleans. His voice, his slumped posture, the weight in his shuffling step, all testified to these burdens and to many other episodes he’d weathered in his youth. But as we ended our six-or-so hours together and I headed back to my motel in the shadow of the Space Needle, I scribbled more optimistic thoughts in my notebook, the most important being that as we’d paged through the leaves of his story he’d brightened and gotten more engaged.

In other words, I’d witnessed the good doctor’s resilience in action. The lows of life, which had sent many of his mentors and friends to their early demise, had strengthened him. Tragedy deepened his soulfuless and his emergence as one of his city’s most iconic performers. Maybe I was reading too much into it, but I felt that he welcomed me into the heart of who he was and what he did more so than most other artist’s I’d been privileged to meet.

That night, at Dimitriou’s Jazz Alley in the Belltown district, my impression was confirmed as we chatted backstage before he kicked off his set. He seemed lighter on his feet, smiled easily, joked with one of the guys in his band. And onstage he electrified the crowd with his second-line, old-school, Crescent City funk. I took the very last seat in the venue, at the bar and behind a pole that blocked my vision completely. But I didn’t need to see what was going on. In his voice and swampy piano style, I could see the neighborhoods he’d described to me a few hours earlier, where the Bourbon Street clubs never closed and the brass bands never stopped marching.

***

Cosimo Matassa

You spent a lot of time hanging around recording studios, from Cosimo Matassa’s J&M Music Shop in New Orleans to Phil Spector’s in L.A. What did those studios mean to you?

Almost every city where I did a lot of sessions, starting at Cosimo’s in New Orleans and even some other studios there … Myself, James Booker, Marcel Richardson, all the young guys, we’d all go there and hope somebody would get sick so maybe we could get on a session. I remember when James Booker would come there. He was already in college, even though he was high school age. I think he was a genius. But anyway, he would come in, do his Bach figures or whatever he was doing, and then he’d sit down and go into what me and Marcel would be waiting to hear, which was all the latest Camille Howard boogies and the latest Lloyd Glenn stuff. He knew everything that we wanted to know. He’d say, “Come on, let’s jam with it!” So I would play the bass, Marcel would play the drums and we never touched the piano while Booker was there. Never! If somebody else came around, they didn’t touch the piano. And a lot of keyboard players was there: Jake Myles used to come out with [trombonist Edgar] “Big Boy” Myles. My point is, Booker was that scary.

Cosimo’s studio was a one-of-a-kind daddy. They had these big old knobs, old-time studio stuff. I remember when Cosimo first got his echo thing. It was this humongous thing, but if a car drove through the driveway it would ruin the tape because all the springs in it would go boi-oi-oi-oing! We’d have to stop. But Red Tyler told me this: He said the first date I played with him, the tape machine wasn’t working and we recorded direct-to-disc. He said, “Don’t you remember? Cos had the discs and he was making a copy where he’d be looking through this little microscope, scraping stuff off.” That’s how he records. To make a copy, he’d be checking the copy the same way, scraping the stuff off the disc. I didn’t really remember that, but when he said that I did vaguely remember it.

One thing I do remember: I guess we were playing on the road together, but Cos would set the machines. He usually had a gofer who would go down to the corner and get him something to eat or whatever he wanted. Some funny people worked for Cos. But I can remember a session. I think it was for [pianist/songwriter] Paul Gayten. He went off. The machines were running. Paul just knew to hit the Stop button if it was a bad take and wait for Cos to come back and get it rolling again. But the saxophone player, when it was time for a solo, just ate the mic with his sax.

Was there just one mic?

No, there was a mic in the piano. There was a mic over the drums. And there was a mic for the guitar amp, a mic for the bass, a vocal mic and a mic for however many horns were on it — they were all on one mic.

This was before multitrack recording.

This was just one track.

How did you balance the performance?

Guys would lean. The guitar player would turn the volume up and then turn it back.

The drum mic would be far away from the drums because they were loud.

Actually, Cos was really good with sounds and knowing the guys, so it depended on who the drummer was. I remember the first thing that faked Cos out was the first date we had an electric bass on. It came way late in the game. Roland Cook came in with a Gibson electric bass and blew out all the speakers in Cosimo’s studio. He hit an open E. After the speakers went, Cos had to cut the session working with earphones. We had no idea what we were cutting because he had only one set of cans. I guess whoever was producing it could hear a little. It really threw everybody a curve. … But Cos knew how to walk around, check the guys and make sure it sounded like what he was getting on tape. That’s the best school of recording, to this day.

The bass guitar on your Mercer and Ellington albums, especially on the song “Fishing,” really pops. The world of bass guitar has changed a lot since those earlier days.

Oh, yeah. Frank Fields, Curtis Mitchell and all those guys I came up with played upright on those takes. But when it switched to the electric bass, it caused a lot of things for the studio. Then Earl Palmer had a set that he kept in the studio. It was called the studio kit, but that was Earl Palmer’s set. Earl had his set at the gig so he didn’t have to carry it. But then Earl went to California and I think Cos might have got in the next studio. There was a hole in the snare. At one point Charles Wilson was the studio drummer. That hole was never fixed, but it sounded so good. Only some drummers brought their kits into sessions, and Cos had to adjust to that. But he would also have to adjust to the guy’s playing. It all went to a new level of that.

At one point, when Earl Palmer left and they were trying drummers, there was a guy named Snow who came in to play drums. He had this strange style of playing. Every drummer I ever heard in my life plays the independence method, pretty much. Well, Snow played, I would call it, the alternation method. It was the funkiest thing you ever heard, but it was damn sure not like your regular drummers.

So he would hit the two and four on the snare …

Sometimes he was not hitting a two or a four on the snare. He might have played the one and three on the snare. Snow just played what Snow played. You tell Snow to play something? Forget it. Snow played what Snow played, and you got what you got. He was just something different.

Each of these New Orleans guys was unique, so when you put them together in different combinations, you always got a different picture.

I knew John Boudreaux and I knew Smokey [Joe Johnson] from around. By the time we were doing sessions together, I was familiar with what they were going to do just from hearing what they did when they’d be playing. But I had heard Boudreaux before that because he was the drummer I used on the Fess thing. We’d worked a gig with Rob Brown at Lincoln Beach, but I also heard him at one club date and he’d be there with a lot of different bands, more than Smokey did at that time. All them cats basically was jazz drummers, but Smokey was the one that caught up with a jazz gig later on. John had a couple of late-night gigs. Smokey was working on Jackson Avenue, and all of a sudden he was playing this gig. I walked in there to see Red Tyler about something. Next thing I know, I heard Smokey, and he was killing me on the drums.

There were so many guys, and they played a different approach to everything you heard. There was a guy named Bones — Eugene Jones; that was Chester Jones’s bass drummer. He had a lot of hungry in him, but he had something different. He played on a couple of hit records, like “Ain’t Got No Home”; he was Frogman’s drummer for a while. At one point he was playing with Sugar Boy [James Crawford]; he did some very innovative versions of what that band did. And that band had some interesting drummers from Day One.

Fess

Talk about some of the great piano players you’ve known in New Orleans.

Well, Archibald worked a club date, like with a small band or solo. The same thing happened with Tuts Washington after he lost his gig with Smiley [Lewis]. It’s a big shift, and then Tuts went back to his roots thing, went back to playing older forms of music. I lost track of Archibald. When I last seen him, him and Cousin Joe was working together, just the two of them. He was great, just doing that.

But then Fess did his thing and never got to do what he wanted to do. That’s the saddest part. We cut this album — I think it was called Crawfish Fiesta — and it was the last time he got to record. He wanted to do this song since I knew him. He wanted to have a bunch of banjos but not playing like banjos — playing like snares. [Doc articulates a swishing kind of street rhythm.] And he wanted a bass drum and a tuba, and he wanted trombones doing these elephant things. I remember that he did something like this with Big Boy Myles when they used to do gigs out at the lakefront with Sugar Boy and the Sha-Weez band. They used to sound like when Dizzy Gillespie did “Manteca” and the trombones would do [he articulates an ascending slide]. He wanted that. So he had this whole pitch. I approached [producer/record store owner] Joe Ruffino and said, “Let me do this one track. Fess has got onto something.” Ruffino laughed in my face. He didn’t know shit. We actually tried to cut it, but we didn’t have all of what he wanted to do it right. We had Johnny Vidacovich playing on some boxes, but that’s not a banjo. I would have loved to have seen Fess did it [sic] when everything was up for him. His chops were the best. He had this whole thing with it that was way better than what we wound up doing even without the instruments, but nobody, including myself, could remember what he had did.

Going West

What caused you to leave New Orleans and head out to L.A.?

[District Attorney] Jim Garrison shut New Orleans down. He padlocked all of these clubs and destroyed the musical strips. And in one moment, everything around me crumpled. I wound up in L.A., staying out by my sister’s. Harold Battiste had this gig with J. W. Alexander, the one who wrote all those songs with Sam Cooke and managed him. A lot of guys were coming through from New Orleans. Plas Johnson and Ray Johnson had been there for years. Plas was like an institution; he was doing all the hip rock ’n’ roll hits. He was Henry Mancini’s guy, doing the Pink Panther and whatever he was doing. There were strings of guys that were connected, so there was a lot of good connects out there in that way that I fell into. Harold got me in through that door to Phil Spector, basically, and then a little bit later Sonny & Cher, which was like cultural shock.

But that history of playing in New Orleans as part of a community, just for the pleasure of playing, with no thought of getting rich … That was like the opposite of the L.A. vibe.

Earl Palmer tried to pull my coat. He’d been out there for years, right off the wheel. He took me for a long ride out there because I said something wrong to one of the contractors. I’d never met a contractor in my life, so he tried to wisen me up. I just didn’t get it. People used me more, I think, as an oddball. Or maybe it was just the name “New Orleans.” I had no idea. Then I doubled on certain instruments. There was a guy there, Larry Knechtel, who doubled on the same instruments as me.

He played the piano on “Bridge Over Troubled Waters.”

He also played on Johnny Rivers’s “Rockin’ Pneumonia.” I kept running into guys out there that I knew from other places. I saw Gaynel Hodge, who wasn’t from New Orleans but he was one of the guys that told me about California before I got there. He wrote “Earth Angel.” And Boogie Daniels was this tenor player that used to work with Charles Brown. There was all these hookups: Gaynel was from Etta James’s family and that helped a little bit. Then from Paul Gayten being out there, I was getting plugged into different areas and getting different gigs. Lee Allen, who was out there at the time, got me some gigs.

But everything about L.A., from having to drive everywhere to dealing with the hippie thing, must have seemed strange to you.

The funniest thing I can remember was something around the Watts riots. John Boudreaux was giving me this ride. We had to go way out of our way. He was coming from Dutone Music or something — the whole thing is foggy — but it was like, “Where the hell am I at?” Then I ran into guys like Dave Dixon. There were certain people, like John Boudreaux and Dave Dixon, that made me feel comfortable out there. Through them I found there was a community of New Orleans people that lived in a certain area, from Adams off of Crenshaw toward the street where the big boxing thing is at. In that little pocket, they used to have a lot of gigs for us. Dave Dixon was always conspiring stuff. Him and Earl King were the funniest guys I knew. Dave would do all these crazy things. He just made it fun. That was my one focus of sanity out there.

“[Phil Spector] was the only guy I knew that had a gay bodyguard.”

At one point I moved into a pad that was, like, seventeen dollars a month, in Hollywood at Van Ness and Melrose, right by the Paramount movie studio. If you was out at the back of the building, you could see the “Cecil B. DeMille” gate. On the other side of it, I was doing all these weird sessions. J. W. Alexander would get me a couple of dates, and Harold would get me one or two where we would do something cool. We did some scab dates with people I liked better, like Little Johnny Taylor. It wasn’t like …

Sonny & Cher?

Actually, Sonny was cool with me as a human being. We might have had one little thing over a song, but other than that, Sonny as a person was good.

You mentioned in your memoir that Phil Spector was a funny guy.

He was so wacked. He could keep you laughing completely because he knew he was out of control. And he was so scared of everything. He had a thing about guns. He was the only guy I knew that had a gay bodyguard. I mean, he had a bodyguard that wouldn’t hurt a fly. Who the hell hires a gay bodyguard? I mean, Phil was out there. I think he was such a frightened guy that the only way he could deal with life was if he wasn’t afraid of his bodyguard. He was way, way out in left field. And all of “wall of sound,” to me, it was just padding on the payroll.

The Doctor Is In

The Dr. John persona was based on history and a real part of who you are, but it must also have been a conscious marketing decision.

You know what’s really funny? In my stupid way of not perceiving marketing or anything, I had some cockeyed desire in my heart to preserve something of the gris-gris music of New Orleans. Already before I left, a lot of it was kind of shattered. Being around a lot of that shifted a lot of gears in my life. That wasn’t like voodoo or something negative; it was just spiritual people that had different understandings of roots and herbs and what people call homeopathic medicine — people that just had some different ways of doing things than the AMA. Personally, I don’t see nothin’ wrong with it. I don’t see a negative side to it, because it works. I never look at it like a religious thing; it’s just a spiritual understanding. People who are spiritual, more power to ’em.

But hippies were into mysticism and tripping out …

Well, that’s why [Atlantic Records President] Ahmet Ertegun released it [Gris-Gris, 1968]. We cut it a year before that. I don’t now what was going on. I do remember staying with some chick that was wangin’ on a guitar, so I guess it was around all of that time. At this point, I think Al Frazier, Jessie Hill and me, we was all staying in this pad. We were still about what we was about. Sonny & Cher’s managers, Charlie Greene and Brian Stone, got me this little pad. I took some time into putting the rest of this record together. Then I went to try and sell it, because I didn’t want these guys in for all of this shit. I didn’t trust those guys, Charlie and Brian. But I had wrote it in chunks at the place on Van Ness, and then I wrote parts in the Eagle Rock area. I had ideas for a record but it just went every way but what I was thinking. Everything kept going different than I thought. I wanted Ronnie Barron to do this; he was my manager at the time. But of course he didn’t like it.

“I said, ‘Didimus, I can’t do this shit, man.’ He said, ‘If fuckin’ Sonny Bono and Bob Dylan can sing, your ass could do that shit.’ Ah, what the fuck, so I tried it.”

By this time we had a whole batch of us from New Orleans. Didimus [Richard Washington] was one of the guys in this Afro-Caribbean band. He gave me the balls to do this. I said, “Didimus, I can’t do this shit, man.” He said, “If fuckin’ Sonny Bono and Bob Dylan can sing, your ass could do that shit.” Ah, what the fuck, so I tried it. Next thing I remember, me and Harold [Battiste] was getting it together. We cut it. We was calling it, at the time, the New Orleans Musicians’ Association of California. We had all the guys; everybody that was there did something. Harold did some hip shit. Plas Johnson had just got an electronic saxophone, and that starts the whole record. It fit that hippie culture thing because you heard this sound and, “What the fuck is that?”

When we did do some gigs, I figured, “well, if we’re going to do this shit, we should mix it with a little New Orleans Mardi Gras and the Rabbit Foot Minstrels shows — the old school.” You know, give ’em a piece of the real McGillicudy. We lucked into a dancer right off the wheel. She knew how to do voodoo dance and she knew how to do classical dance, like ballet, and she knew how to do jazz dancing. So we’d just stand her right there, let her take her thing off and she was naked — and we had [a full] house.

Who’s Jivin’ Who?

You’ve become kind of an ambassador for New Orleans, picking up from where Louis Armstrong left it.

I’m very proud to have been born in the neighborhood of New Orleans where Louis Armstrong was born. My father said, “Louis” Armstrong; he would never say “Louie.” He used to point at where he was born — not from the hurricane, it was gone thirty years before that. There’s a park named after him, an airport named after him. But why don’t they have the pad where he was born? Why didn’t they just move it somewhere? It’s like a historical thing to me. Everybody in our neighborhood knows about that.

Anyway, I do feel some responsibility. I don’t know if it’s an “ambassador,” but now that you mentioned us, when Joe Glaser president of the Associated Booking Corporation] signed us up back in the Sixties, I actually met Louis Armstrong. I never met him in New Orleans. Maybe there’s a weird spiritual or mystical thing. So does Wynton Marsalis. Listen, he’s a much more eloquent spokesman than me, so I give it to him [laughs] or anybody else who’s staying there.

But all of us take some love and pride in our roots, to the point that we all do a thing and whatever it is, we all appreciate and love each other’s music. We all came out of a certain thing. You got extreme toots [sic] of New Orleans, whether you go to Harry Connick Jr. or the Mardi Gras Indians, from Branford Marsalis to the Neville Brothers. You can keep waltzin’ from whatever extreme you want and it’s all part of New Orleans.

But isn’t it different now, since Hurricane Katrina?

It’s way different and it’s very scary because it’s gonna take a long time to try and put chunks together, with no help coming in from any apparent source, with so much lies being told.

Is it possible the city never really will come back?

Well, there’s chunks that’s back, but that creeps me out because it’s so not New Orleans of the whole. So many people would love to come back. So many businesses can’t function without the people that ain’t back. It’s pathetic.

Listen, when you look at all the funk rhythms and all of the stuff that came from the Seventh, Eighth and Ninth Wards in New Orleans, they took a bad hit. The music that came out of the Second,Third and Fourth Wards took a bad hit. The people out at the lakefront may have a little more money, but they took a bad hit. There’s a lot of areas there that ain’t being fixed. It’s very unbalanced on every level. I hear people rationablize the fact that, “You have to fix it from the higher ground and work your way to the lower ground.” Well, what of the thirty thousand people that have nowhere to go? That don’t have a FEMA trailer or they’re paying rent in New Orleans and playing elsewhere and can’t make ends meet because of FEMA? I get very angry. It just goes on and on. Who’s jivin’ who? The mayor showed gross incompetence. The governor showed gross incompetence. I’ve heard politicians lie all my life. I’m from Louisiana; I’ve heard ’em all. I worked gigs for people I couldn’t believe they got voted in [laughs]. But now what I grew up seeing is common in America. It’s all over the place. What is wrong here? It bothers me drastically.

When you were watching the hurricane build while on tour in Minneapolis, did you feel relief at first that it missed the city?

The humongous size of this hurricane had me totally freaked. I’d never seen a hurricane big this way in my life. This looked like it to me. I’ve heard all my life that hurricanes go up that way. When it’s up the river, it’s all over. But I’ve also always heard that if a hurricane got big enough, and they didn’t do something with the levees and they didn’t do something with the levees …

The saddest part is that all your Cajun people who live on the Bayou had been told in every meeting with the Corps of Engineers for all these years and were not given a vote because they didn’t live in Orleans Parish. But they are the people who lived where they could see what was happening. Like, where Hurricane Rita hit at Homer, Louisiana, where Bobby Charles, that wrote “Walkin’ To New Orleans” … where he was living is gone. That hurricane just took it out. Now, I would think that somebody in the government would say, “We should protect that whole Gulf Coast region.” You talk about terrorists? It didn’t take a terrorist to put that much damage out there. What they say, in FEMA bylaws, is that in six months they’re supposed to have most of the problem resolved. It’s been a little over six months [since Hurricane Katrina] and it don’t seem to me that anything too much has been resolved. I’m not too thrilled with FEMA, obviously. But it’s like all the ongoings with the federal government and the state government. It’s like, who are they kidding?

Bobby Charles wrote a song: “The road to the White House is paved with lies, lies, lies, but the truth will set you free [from “Promises, Promises (The Truth Will Set You Free)”].” I’ve been singing that on gigs and I don’t even know the melody [laughs]. Bobby’s one of them great songwriters. We’ve written songs together. I love what he does. But he’s so miserable right now. I don’t even have a good number on him. I had a number, but I had one of these [Doc holds up his cell phone] and it died. I lost all my numbers. I went into a mode that said “no signal.” But he knows my damn number. Listen, if I hear from that sucker, I’m gonna cuss him out.

It’s a problem. There are so many people, guys that are getting back who are too old or too young to deal with it. I had a friend who’s been down there for months, almost since you could get back. He got his FEMA trailer. They didn’t give him a key. He worked and worked and got his key, and he was going to pick up one of his kids who just wanted to see New Orleans. They said, “We’re going to get your lights on”; he’d been living with candles. He brings the kid in — no lights. The kid has to see how his daddy’s been living. It’s just one story in a million. Everybody down there, you could say, “How’d you do?” It could be an epic movie.

What about you and your family?

I’m in New York, but I got family there. So far everybody’s okay. I’m looking at it like this: It’s phenomenal how many things goes on. If I put all of my concern over all of the friends I lost, I could put all my concern on the daughter I lost. I could put all my concerns here and there, but I could flip out and I can’t do anything. So I try to do the best I can with all of it, but it’s not an easy road to follow sometimes. The word is … “convoluted.”

####

What a great interview! Thanks.