There’s no place like home, said that little girl with the red slippers. For me, in the early-to-mid Seventies, “home” meant Austin, Texas. But my living there had nothing to do with it, because with or without me, there was no place like that quirky, vital, unforgettable town.

Oat Willie’s, hawking its “Keep Austin Weird” bumper sticker. Ice cream amidst blinding psychedelic lights at Nothing Strikes Back. Midnight runs to Mrs. Johnson’s Bakery, where the donuts were always steamy fresh. That little bearded guy screaming “smile” at passers-by on The Drag, i.e. Guadalupe Street bordering the UT campus. All-night comfort food at Les Amis. Burning hot summer days in the icy waters of Barton Springs or at the Colorado River’s clothing-optional Hippie Hollow. Yodel master Ken Threadgill drinking beer straight from the pitcher between songs at the Broken Spoke. Doug Sahm and Augie Myers ending each gig by advising fans to “don’t take no shit from nobody.” Rednecks and “cosmic cowboys” line dancing together to Asleep at the Wheel at Arky’s Dessau Dance Hall. The gorgeous fiddler Mary Egan, drawing all eyes away from her colleagues in Greezy Wheels. Music all over town, every day: The Split Rail. The One Knite, across the street from the raucous New Orleans Club, which used a coffin as its front door. The Rolling Hills Country Club, a.k.a. the Soap Creek Saloon. The Saxon Pub. Mother Earth, out on Lamar. Bevo’s, steps away from my old flat, which my appalled father dubbed “the Black Hole.”

But the Mecca of Austin music was the Armadillo World Headquarters. Being a regular customer was like taking a grad course on contemporary music genres, except with beer. Blues guitar powerhouse Freddie King. Bluegrass godfather Bill Monroe. Frank Zappa. Bruce Springsteen. Of course Willie & Waylon. The one thread binding these diverse artists was the emcee who expounded on what to expect just before the music began. I remember him very clearly, not so much from his introductions as from his outfit: long black robe and headgear fashioned to resemble an armadillo.

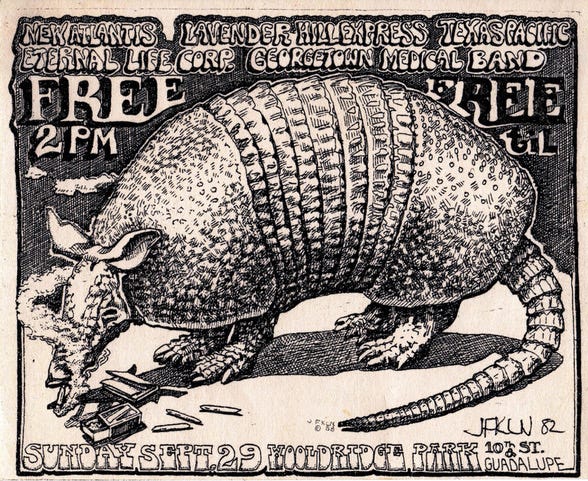

Franklin was even more revered for his visual artistry. Beginning with a handbill designed for a “love-in” in 1969, which featured a joint-smoking armadillo, Franklin defined the technique, attitude and bizarre surrealism personified in Austin poster art. Inspired by but fundamentally distinct from the Haight-Ashbury creations in the mid-Sixties, the work of Franklin and those he inspired captured the vibe of that time in that place as few other movements could do.

When the Country Music Hall of Fame announced its exhibition of posters by Franklin and other Austin poster pioneers, I immediately pitched Nashville Arts magazine. They wisely reciprocated, and I ended up interviewing Franklin and fellow poster artist Guy Juke for the piece. Unfortunately, NA gave me a very tight word count, which meant I had room for only one quote from each artist. Luckily, I saved the transcripts, and while Jukes’ recollections are illuminating and vital, Franklin was the movement’s progenitor; as Juke put it to me, “It all started with Jim Franklin.”

****

Is this the first exhibition of Austin artists from that era?

Not really. There have been events all along. I always looked forward to having this poster trip become an introduction to the artists’ more serious work and an area of private work the public seldom sees, where deeper ideas are delineated. A lot of the time some of the freshest thinking gets edited down through a process of making an advertisement or something.

Did you help facilitate this show?

Not really. The points of contact were already well established when artists like Guy Juke and Danny Garrett — the Armadillo poster crew. Most of us still have flesh on our bones, so it’s kind of interesting that it’s happening at a time when we’re all still available [laughs].

PULL QUOTE: “Trying to do this abstract monetary thing was an aesthetic stupidity for me.”

Talk about the synchronicity between the visual art and the music that was happening in Austin at that time.

For me, it was more of an energy pool than a direct input. Sometimes there were specific pieces, at least in my approach, that were inspired by some element of the band — its name or some special occasion for a concert. It was more of an excuse to get a piece of art done, more so than a desire to worship any musician. To me, art and music are equal endeavors. They’re equally valid as mediums of expressions [sic]. It’s just that some of them get staged more than the others. They get more attention because of the medium they’re in.

By the time I came to Austin I had developed this philosophy about “no commercialism in my art.” I realized early on through an experience with one of my first mentors in Galveston, a superb painter who became a commercial artist and illustrator for a magazine. He gradually stopped painting. I could not let that happen to me. He could give me a job to work on and I’d just be frozen. I couldn’t make myself move my hand one inch to design this logo for a [unintelligible] thing. If I could take my paintbox or easel and go out to the beach, I’d have a full painting done in three hours because that’s where I should be. But trying to do this abstract monetary thing was an aesthetic stupidity for me. You have to relinquish your creative flow in order to do a mundane thing with a pen.

Who did you know in Austin when you arrived?

Actually, some of these guys were key to getting me to come to Austin from Galveston, like Travis Rivers and Ed Gwinn. They were movers in the beat scene. I’d met them in a coffeehouse in Galveston. They encouraged me to come to Austin. So I did. Some mutual friends were musicians. I had some experience in graphic art, so I started doing some posters for them. Unfortunately for the city of Austin and the whole culture, Gilbert Shelton had been an art student at UT, and he had learned about layout and things like that from working on The Ranger. I never was a student at UT. In fact, I never saw a copy of The Ranger until after I’d been drawing armadillos for about a year. Dave Hickey, who had the Clean Well-Lighted Place gallery, showed me some copies because he wondered if I’d ever seen Glenn Whitehead’s armadillo drawings for The Ranger. I said, “Wow! Somebody else was drawing these?” It was so wild because I’d been hanging out at the Chuckwagon every day, and I never saw a single hint of an image of an armadillo.

A lot of people assume I’d been a student at UT, and that’s where I picked up on the armadillo, which was completely wrong in my case. When I started doing posters, I violated that rule of mine about doing no commercial art. Someone requested a concert image. I felt like, “Okay, it’s not commercial art in the sense that toothpaste is sold in a store. It’s art for music. That’s a clean promotion.” I allowed myself to go down that alleyway [laughs].

Robert Crumb followed a path similar to yours.

Yeah, he worked for one of the big greeting card companies.

SUBHEAD: The Poet’s Dilemma

Austin wasn’t a corporate scene but rather a legitimate grass-roots artistic explosion.

It was the authentic thing of artists doing their thing in a state like Texas where creative activities are not necessarily encouraged. It’s a thing that queers and sissies and women do. I composed a poem on my first day of senior English after spending the summer in Kansas City and being turned on to William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti through the City Lights Bookstore publishing. I got turned on to free-verse poetry. So the first day in English, Mrs. Green, whose son had been a tuba player and played solo tuba on The Ted Mack Amateur Hour and performed onstage at our high school auditorium … I was just blown away that this homely-looking guy was up there with a tuba, blowing our minds! And his mother was my English teacher in my senior year! I’d taken speech and was into acting, drama and all that stuff the previous year, so I was really ready to write and read my own poems. I’d already been doing that a little bit but I really got started after that summer in Kansas City.

So she said, “For your first assignment, everyone write a poem.” I wrote a free-verse thing about the sensation of falling. She was sitting in the back of the room. I turned it in. So she reads over the poem and announces, “There’s a poet in our class: Jim Franklin.” And everybody around me booed and hissed. I couldn’t understand: Where did fucking get that attitude? Somehow they already had an attitude about poetry, which came from their brothers and their daddies and those football-playing motherfuckers who have fucked up our culture. That’s not what nature’s all about. It’s not about moving a ball around a field. You plant things in the field and make them grow! We were all victims of ball-playing in a major industrial suburb. We had a welded metal and wood football stadium but no art class for four years. Art was something you did not do in that world. Art is something you do if you’re a woman and you’re retired.

I wanted my art to be an expression of my life. From first grade on, I became a skeptic about the Baptist Church. I developed a real resentment to their presumptuousness about my thinking and my activities. They never even bothered to question me about their thinking. They just had me there every Sunday, presuming that I’m guilty of eternal crimes! That offended me all through my childhood. I knew you had to stand on your tongue or you’d get in trouble speaking about this shit.

Finally, I got to the point where I started commenting on my own terms as far as being an artist. By the time I was in high school, I’d kind of mastered painting and drawing. I’d excelled and continued to expand on it from first grade on. By the time I was in junior high I was an accomplished artist in a sense, if you consider the state of that age and what I had to work with. This all happened in a blank petri dish.

Texas had plenty of symbols already: longhorns, Stetson hats. The armadillo is perfect for the counterculture, though, as a humbler icon.

I wasn’t out looking for an icon, a signature animal. When I was in high school I had this hunting trip with my father. We were creeping up on what we thought was a deer. I’m behind him with a little rifle. We got up to where the noise was and it was this armadillo! I didn’t even see it; my dad saw it. It was the only time I ever heard him laugh. That was not a place for humor; that was serious stuff. So I finally saw an armadillo in the field. He flipped under the barbed wire and started creeping up. I didn’t know anything about him but he’d stand up, check for danger and go back to digging. I got right up to within five feet of it when he turned and walked between my legs, in the woods in the middle of hunting season. That made a real strong impression on me, to be that close to a wild animal.

PULL QUOTE:

“‘Don’t make any suggestions.’ … That was my number one rule. The other one was, ‘If you want to pay me, I’d appreciate it.’”

I also tell people, “Don’t make any suggestions.” I just found out last year that I have ODS, which is oppositional defiance syndrome. That’s been a lucky thing for me because it keeps my art original. If you want me to do a poster, don’t make any suggestions. It might be what I’ve been thinking, but if you say it, I won’t do it. That was my number one rule. The other one was, “If you want to pay me, I’d appreciate it.”

SUBHEAD: The Jazz Life

You spent time at the San Francisco Art Institute. Did being in that town inspire you to explore poster art and help develop an indigenous style in Austin?

When I went out there, jazz was the main thing for me. That was the dominating culture. San Francisco had become a jazz scene. There was one nightclub called the Black Hawk, which had a screened-in section for underaged customers where they couldn’t get drinks but they could watch the show. I went there the very first night I was in town, after I’d checked into the Y. Gerry Mulligan was playing. I saw Miles Davis at the Black Hawk. Then down on Grant Street and Broadway, I saw Cannonball Adderley, Horace Silver and all these great people at the Jazz Workshop. I even saw Lightnin’ Hopkins, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee at the Sugar Hill, which was a blues club across Broadway from the Jazz Workshop.

By that time I’d rented a room on Grant Street, around the corner from West Broadway, where all these jazz clubs were. I got out of the art school thing, being a day late for Fall registration, so I took night courses. I felt like I was ready to move on with developing my art and not having to do it in an athletic environment. A lot of the universities are identified by the football teams. Their entire learning process seems to be a sporting competition. That keeps things moving but at the same time it has this winner/loser thing, which is not an appealing thing for acquiring information. Anything that has too much of a relationship with football and that kind of sport is not the real thing. It’s a distraction from something. It takes our money and our energy. I can’t wear anything that I see on the football field. I don’t wear a helmet. I don’t want my shoulders to be super-exaggerated. They don’t even look like humans! At least in soccer you can see their bodies! Even if you’re not interested in points or the game, you can at least see humans move!

What can you say to readers of Nashville Arts to give them the background they need to appreciate what they’ll see?

It’s interesting how it relates to the music scene. One way to do a music poster of a performer is to do a portrait. What was developing in Austin, as well as in San Francisco and places where art was meeting the music world, was the meeting of Surrealism and psychedelia. When I started drawing for the genre, I started tapping into my Surrealist — Magritte more so than Crumb. Crumb was dipping into the same sources. We were all dipping into the weird aspects that had been revealed about Western art over these past three hundred years. We were the expressive edge, like the waves breaking on the shore.

PULL QUOTE: “I want to bring out the meaninglessness of the apparent related elements that make everything meaningful.”

Each of the artists in the Nashville show is a distinctive artist. What are the common elements that unify Austin artists in that period of time?

It was inspired a lot by underground comics and San Francisco posters. It had a lot to do with pen and ink, the drawings that come out from doing crosshatch shading. And comic books: They’re a way to make a quick literary statement. I want to bring out the meaninglessness of the apparent related elements that make everything meaningful [laughs]. It all boils down to arbitrary shape and face. When you see it that way, anything becomes possible. That can reverberate through the entire time you’re watching a show or hearing a record. That’s kind of what was happening in Austin. I like the word “Surrealism.” It’s an attitude toward the discovery and relationships of forms.

This work shares a combination of strong academic technique and an appreciation for anarchy.

That’s one of the strengths of the longevity of our whole trip, the fact that we were based on actual drawing skill. We inspired a lot of people who came along later who started doing “clip art,” where you put something on a Xerox machine and it all looks edgy and modern. But they weren’t really drawing; the creative part was how they arranged these scraps on paper. They were getting away from skilled draftsmanship but they still wanted to put together these crazy ideas. You can see that fully manifested in graffiti art, which has become fine mural art.

This demonstrates that art is not just arbitrary, second-hand afterthoughts. It is a creative activity. Art is what you use to express an idea. Industry has a tendency to cast truly creative persons when it’s actually the opposite of what happens. We create the original concept for the others who have something to serve.

(Note: To see Country Music Hall of Fame’s Austin poster exhibit, visit https://www.countrymusichalloffame.org/press/releases/high-resolution-photos-outlaws-armadillos-countrys-roaring-70s-art)

###

Thanks, Tom. I am so lucky to have spent three years during the Austin's halcyon era. I'm sure we were in close proximity to each other on one or more nights at the Armadillo. Great, great days (and nights!).

In the early 70s I discovered JF on a Freddie King CD Shelter released. Then I had the luck to meet a guy in FLA, recent Austin transplant, whose living room art included three works--posters and prints. They always represented the magic of what we heard was going on in Austin, and his presence as "artist of the Armadillo) put him in the same important group at Rick Griffin, Moscoso, Crumb and the great poster artists in San Francisco. As such he is one of the few artists who helped define that very active Austin scene. His stuff still brings a smile to my face and loosens memories of my first trips to Austin years later, when the music scene there was bubbling with creativity. Sadly, those heady times are just a memory now, with the Austin scene a shadow of what it was then.