Randy Newman

Keyboard Magazine, February 1989

Only a few months after I’d moved to New York to edit Musician Magazine, I ran into somebody who was apparently Randy Newman’s manager. We talked for a second, and then he said, “Did you know that you look exactly like Randy? Actually, you sound like Randy!”

I nodded and said something funny, I hope. But I was thinking to myself, “That’s the nicest thing anyone has said to me in years!”

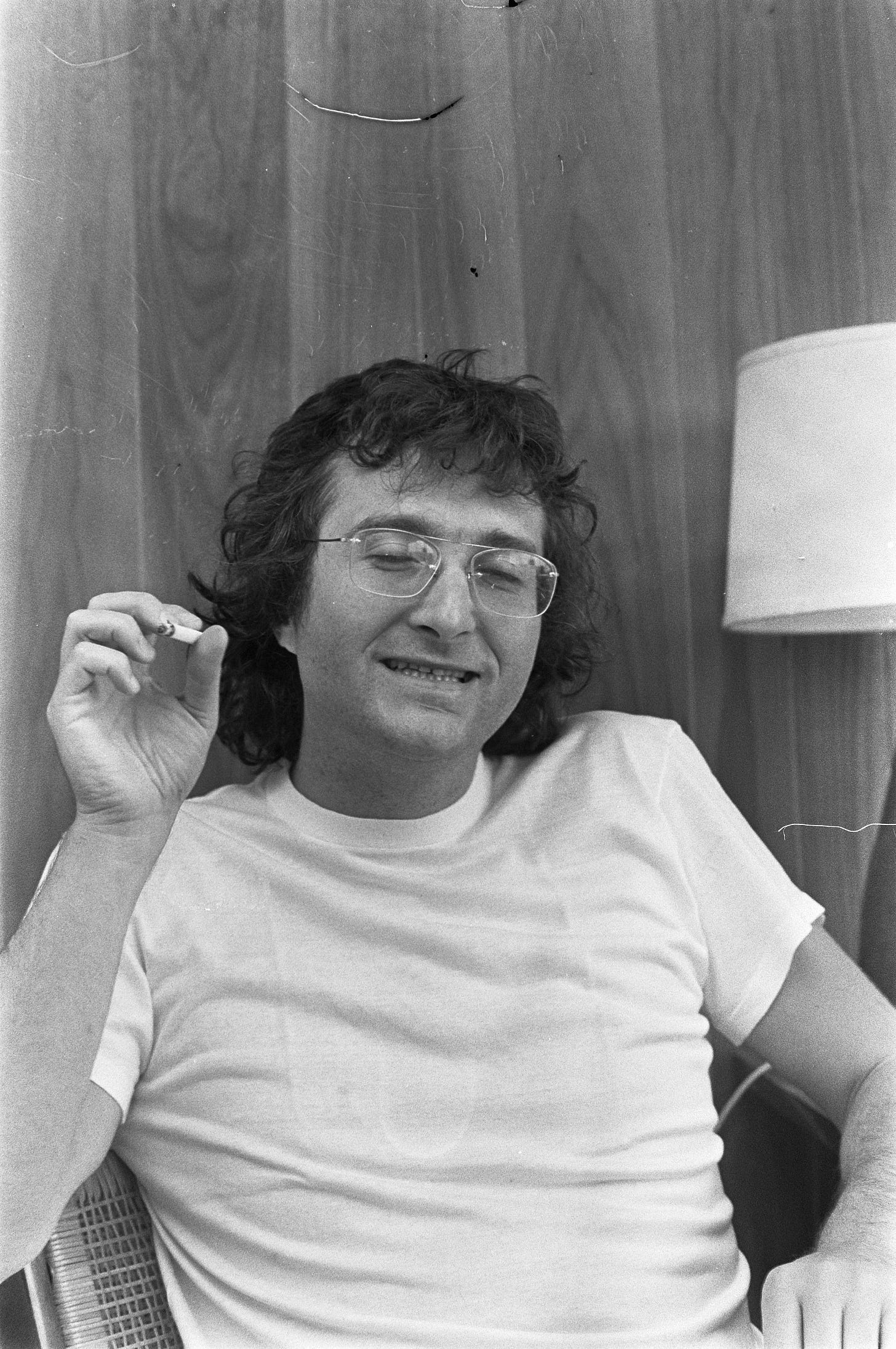

Looking back, the comparison may have been apt. I mean, look at this photo of Randy, taken in 1974:

If you knew me back then, you might not believe this isn’t actually me in the picture. At least in my imagination, I looked exactly like this, back in the Nineties. Certainly it looks more like me than Toto keyboardist Steve Porcaro did, when I was by chance seated next to him on a flight from San Jose to Burbank back in the late Seventies. I mentioned that some folks in my office had remarked on our resemblances: long hair, glasses, keyboard players.

“Yes,” he replied. “But the difference is, I’m a rock star.”

Of course, he was right, so I bore no ill will then nor do I now. But Randy and me? We could have been twins, at least at one stage of our lives. And not just physically: His sardonic lyrics, often juxtaposed against delicate or sweeping romantic orchestral accompaniments, resonated with me. Nobody else I was aware of could write a feather-fragile string part and make it work with lines like, “Sometimes I’m crazy, but I guess you know. I’m weak and I’m lazy and I hurt you so. And I don’t listen to a word you say. And when you’re in trouble I turn away. But I loved you the first time I saw you. And I always will love you, Marie.”

Or, from the same album, Good Old Boys, this snippet from “Rednecks”: “We’re rednecks, rednecks. We don’t know our ass from a hole in the ground. We’re rednecks, rednecks. We’re keepin’ the niggers down.” But when Newman delivered these alarming sympathies, he did so with a deadpan vocal that became his trademark, as if he were Christopher Hitchens quoting indefensible scripture back to a tongue-tied cleric. “Don’t blame me,” Newman and Hitchens seem to say. “This is just the truth, no matter how infuriating it is to you.”

Keyboard Magazine sent me to L.A. for this interview shortly after the release of Newman’s album Land of Dreams, a largely autobiographical collection of mismatched Oscar Levant cynicism set to wistful, nostalgic melodies. It was in that sense a typical Newman project. On the opening track, “Dixie Flyer,” he eulogized his family’s migration from Europe to the America’s East Coast and down to New Orleans: “Drinkin’ rye whiskey from a flask in the back seat, tryin’ to do like the Gentiles do. Christ, they wanted to be Gentiles too. Who wouldn’t down there, wouldn’t you? An American Christian? God damn!”

When we met, at his manager Peter Asher’s studio a block or two from Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, Newman evinced some discomfort. The music industry was in the midst of a revolution in electronic keyboard design. For more than a decade, one amazing development after another had exploded the limits of what these instruments could do. Designers at Yamaha, Roland, Korg, Sequential Circuits, Oberheim and other companies challenged each other in quick succession, introducing polyphony, then touch-sensitive keyboards, then digital technology, sequencing, sampling … For some pianists, including Newman (and myself), these developments were as intimidating as they were inspiring to others.

So, naturally, that became a focus of our conversation, partially to address the perspective many of our readers would bring to assessing Land of Dreams. Inevitably, this being Randy Newman, his words were fascinating, even entertaining, despite the limits I’d staked out. In fact, I’ve edited out much of the transcript’s lengthier ruminations on music technology, which some thirty-six years later seems more quaint than cutting-edge.

***

Speaking as a pianist, how does the state of the keyboard art look to you these days?

Soundin’ great! All this new stuff is enabling people who aren’t literate in the strict musical sense of writing stuff down to bypass the traditional way of making music. It’s allowing people who just have keyboard facility to make music that isn’t exactly orchestral, but almost.

Are you saying that’s a good thing, or a mixture of good and bad?

It’s not a good thing for me or John Williams. It’s a good thing for Peter Gabriel and Sting, and for music in general. Why not? Music sounds better now than it ever did before. Some of these dance records are so fancy! The content isn’t there, though. It’s like a lot of pretty packages with nothing inside.

How has contemporary music technology affected the craft of songwriting?

A monkey can make something sound good now. You can take one of those little Casios, add a drum program and it doesn’t sound bad. I used to sit in the studio with [synthesist Michael] Boddicker, layering sounds. The new stuff devalues the premium on that kind of talent. I can still hear when somebody’s really good, but it’s not as easy, because all those sounds are just out there for people to grab.

If you were coming up today as a songwriter, would these tools influence you to write different types of songs than you did in the Sixties and Seventies?

If I had grown up on synthesizer instead of piano? Certainly. That’s how one of my cousins was raised, although he also plays piano better than I do. If you’re sounding good, you might just say, “My girlfriend and me went down to the beach.” If you’ve got some good sounds happening in the background, that’s sort of okay. A lot of the stuff I like to listen to is like Hall & Oates, which sounds so great that it doesn’t matter what they’re saying.

…

Has working with electronic gear affected how you use piano sounds within an orchestral arrangement?

No. I’ve spent years struggling with whether it goes with an electric guitar. I never used to think that it fit. I don’t like the fact that on “Dixie Flyer” the piano doesn’t quite sound real. It’s very close because of the things that [engineer] Frank Wolf did, like running the sound through a room or through a real piano with things put on the strings. But it wasn’t a real piano. We did that on a Synclavier.

It’s hard to tell that within the arrangement.

I can tell. Maybe it sounds like an old English piano from the nineteenth century that has no balls. I don’t mind how tinkly it sounds at the beginning, but when the voice comes in it doesn’t play in those chords well. That’s not a real piano in “Bad News from Home” either. I don’t mind that too much.

Mark Knoplfer produced both of those songs. You also recruited Jeff Lynne and James Newton Howard to produce the rest of them. How did you determine who you would use on each cut?

They each heard my demo at different times and picked ’em really fast. I can’t remember who had the first pick. Actually, I think Russ Titelman did. When I started working with Mark, Russ was busy, so I just kept working with Mark. They all wanted to do “Falling in Love” but Jeff got it. I’m surprised that Mark picked “Bad News from Home.” I had written a few other songs, one of which I would have recorded ahead of “Bad News from Home.” But it turned out very well. Mark is a much more meticulous fellow about recording than I am. I’ve never seen anyone as meticulous about words, orchestra sounds and synthesizer sounds. I’m impatient with little nuances. I’ll ignore a lot of important things: tuning, time, stuff like that.

That’s a refreshing attitude, given that attitude you mentioned in pop music, of sacrificing the human essence of music through preoccupation with technical perfection.

That’s all a lot of guys can do. I just heard a guy being interviewed on the radio. I hadn’t heard his music yet, but he was very intelligent. He’s done TV and movie work, and he’s very personable. Then they turn his music on … and there’s no talent. Not a trace, I’m sorry to say. These people can quantize the shit out of you, but that’s all they can do. Fingers, but no notes. A lot of them make very good money. Sometimes it’s like Amadeus in that the people who get given the talent are dopes. They’re not often nice people that you’d like to know.

“If Dylan came along now, I don’t know if anyone would notice.”

But do the most talented people eventually find success?

If you’re an acoustic guitar player and you’re talented, even if your talent is as extreme as Dylan’s, I don’t think you’ll make it.

In other words, the odds are heavier against talented people than they were twenty years ago?

Oh, yeah.

Why?

Because things that sound good are so seductive that they squeeze that stuff out. I’m very surprised that Tracy Chapman has come this far. But if Dylan came along now, I don’t know if anyone would notice. You could do the greatest album of all time and nobody would know about it, because it might not get on the radio. Would any of Sgt. Pepper get on the radio? God, no. And that was probably the best rock album ever made.

Maybe people like Tracy Chapman are the antidote to all those robotic dance tracks.

Maybe. But it’s hard to get really tired of that dance stuff. It’s just disco with another name. I dan listen to it for a long time and not notice that it’s just a beat. A beat is a powerful thing. When you listen to the radio, when you go dancing, you’re not in it for the words. That’s true for me, even though words are crucial to me. That’s what I do for a living. I’m not a snob. I’ll use three chords if I want to. I got this record by George Jones, Anniversary, and I’m telling you, I don’t get tired of it. That stuff is so great: “The Door,” “The Grand Tour,” “Bartender’s Blues, “The Same Old Me.” I mean, I embarrassed my kid in front of his friends. I take him to where they’re gonna be playing and when he gets out of the car, here’s George Jones booming out. I love that stuff so much, it scares me! I bought this record of Brahms’ Fourth Symphony, conducted by [Carlo Maria] Giulini, but all I play is this George Jones shit. I can’t stop! I don’t think I’ve ever loved anything as much since Ray Charles.

Of all those people back then, I really liked Ray Charles and Fats Domino the best. I’ve bought maybe five singles in my life, and two or three of them were from really obscure New Orleans artists. One was called “Rockin’ Charlie.” I also bought the original version of “Irresistible You,” “Sticks and Stones” by Ray Charles, “From Me to You” by the Beatles and “House of the Rising Sun” by the Animals.

That music was an obvious influence on how you play and write for the piano.

Yeah. It’s almost like racism! I was talking to Jerry Leiber when I was about nineteen, and I said, “Geez, how can I stop doing all these straight [i.e., unsyncopated] eighth-notes?” He said, “Don’t worry. Just keep working. You’ll write yourself out of it.” Well, I tried to stop. I’m still trying to stop. I don’t do it as well as Dr. John, who puts little turns on top of it. But it’s my natural idiom. Thomas Dolby’s natural idiom is a little hipper, and it will do him more good than mine does for me. Mine, for some odd reason, is this Fats Domino kind of shuffle. Drummers don’t like it. I don’t like it! But it feels good to me. It feels good to play my stuff on the piano. I don’t have a drum with me, so the shuffle gives me some sort of a beat.

What about jazz? Did any of the great jazz pianists influence your playing?

Not much. I’m embarrassed to say that I’ve just discovered what a good composer Duke Ellington was. “Caravan” is one of the hippest records I’ve ever heard. I play it every morning. I like Thelonious Monk. He has a sense of humor, which is very rare. But I don’t have much tolerance for a guy taking a half-hour solo – you know, “Roger’s Ruminations,” where some guy sits there in Tokyo and plays for forty minutes. Who gives a fuck? In forty minutes, you can play a Tchaikovsky concerto.

…

String Theory

As a songwriter, do you have any interest in compositional software?

Some. But God knows, if something makes me the same as fifty other people who are using it, what the hell’s the use of it?

But wouldn’t you benefit from having a setup where you can play back electronic approximations of orchestral timbres as you work?

Maybe. It’s awful scary writing for orchestra. It’s always scared the shit out of me. I would think, “God, these strings are gonna sound terrible. This isn’t gonna work.” But you don’t really get an accurate picture with electronics. It isn’t real. You might learn a few little things about string writing. Maybe I just don’t know. Maybe I just haven’t heard it be real.

Have you tried using orchestral samples as a guide to arranging for real orchestra?

No. I just talk to someone like James [Newton Howard, session keyboardist], who knows what he’s doing: “Less of this. More of that. He knows about all this stuff, an AK-47 or whatever it is, can do.

“Kids are going to read this and say, ‘What a fucking snotty asshole!’”

Isn’t the Ak-47 a rifle?

Isn’t that pathetic? I’ve become an old crock. Kids are going to read this and say, “What afucking snotty asshole!” I sound angry, but I’m not. I use all this electronic stuff. I just wish I didn’t have to know any of it. Knowing the range of a clarinet is enough trouble. I mean, I’d give anything to love it all.

One of my cousins was talking about somebody, and he was really excited. He said, “This guy has a whole bay of synthesizers.” I wanted to kill him. Why is he so interested in this shit? But I’ve always wanted to love it too, like James. He got this new Yamaha stuff, so he wanted to put this Yamaha guy’s name on my record: “Thanks to Doug Buttleman [director of Yamaha’s Sound Check artist relations program. James has that on his records. Well, what has Doug Buttleman ever done for me? I like the guy, but I told my lawyer that I didn’t want to put his name on my album. So he says to me, “Well, then, why don’t you change the name of the record to Land of Yamaha? That should make everybody happy.”

…

Would you like to go back to scoring for real orchestra someday?

Yeah. I like it. By choice, I would use a real orchestra. My heart is with the orchestra. I’d use it, even if it were sloppy. And I’ve done ’em sloppy. I’ve conducted some things so slow that I couldn’t even sing ’em.

Such as?

“Davey the Fat Boy,” on the first record I ever did. I just heard “Old Man” [from Sail Away] on the radio the other day. It sounded really beautiful. The orchestral guys really played well for me. But the tempos were all fucked up.

Did you ever conduct an orchestra from the piano bench?

Never. It would have to be separate, like on “Old Man”: First there’d be strings, then plink! They stop and the piano comes in. Sometimes I have to have [session ace] Ralph Grierson play for me. I think Grierson played on “Real Emotional Girl” and “Same Girl” [from Trouble in Paradise].

He was on “Texas Girl at the Funeral of Her Father” [from Little Criminals] too.

Yeah. He played on that. Did very well too.

His playing sounded just like yours.

It really did. Well, not exactly.

Are you interested in doing more freelance arranging?

Sure. If I see a movie I like, I’ll do a soundtrack. I’ve done two big orchestral soundtracks, Ragtime and The Natural, although The Natural had quite a bit of synth on it. I’ll do any movie where I thought the music would be important and the movie itself isn’t horrible.

Your scores thus far go for a kind of a nostalgic feel. Would you like to tackle a more adventurous type of score?

Oh, yeah. In fact, I’d rather do that, on something like a horror movie. I’ve done these Americana things, but I can do the other stuff too. Actually, the more outside stuff is easier. I’ve seen movies I would have done in a second if someone had offered them to me: Out of Africa, Last Temptation of Christ.

What criteria do you have for accepting a soundtrack job?

It depends on how important the music is. My Life as a Dog was a great picture, but I wouldn’t have done the soundtrack. What would be the point?

What purpose does music serve in a movie?

There are billions of things.

Generally, though, should a soundtrack work subliminally, or should it be more prominent?

Subliminal. Sometimes you’ve got to be noticed, but mainly you’re trying to amplify the picture. Or you’re trying to warm something up. That was required in lots of spots in The Natural. But you don’t want to be out there doing your own thing and being antagonistic to the picture. Doing this kind of work is an exercise in ego management, because you’re not your own master. You’re boxed in. Here’s a guy running around the bases in The Natural, so you’ve got a minute and twenty-three seconds to fill. They’re kissing: You’ve got twenty-five seconds.

As someone who has worked hard at the craft of orchestral writing, do you resent musicians who write arrangements through trial and error on electronic gear?

Maybe a little bit, although not, I would imagine, like some of the movie guys might. To be honest, when we did Born Again, I thought that we had some of the best synth sounds that people were making at that time. It probably still sounds really good, if anybody could find it. We cared about those sounds.

Nowadays, of course, you hear unbelievable stuff. The Peter Gabriel record [So] sounds so great. I heard a Loverboy record that sounded like a talented person was doing the keyboard stuff. He did some really interesting sound. And Prince’s stuff! Prince is not afraid to have no echo on the snare. See, I do know more about snare sounds now! In the Seventies, there was always this attempt to get this deep snare sound, like it was a tom-tom or something. People would spend years on it. But Prince changed things around. You hear nothing on his snares. It’s just a crappy little drum. But as far as what all these guys are doing, none of it is really a threat. They can’t do what Johnny [Williams] can do with an orchestra, or what I can do. Not with all this stuff. Not now. Not ever!

###

Wonderful! Having lived most of my life in the South, it’s always rankled me to hear self righteous northerners talk about the evils “down there”. As if it was nonexistent everywhere else. I always tell tell them to listen to Newman’s “Rednecks” and come back for a chat. Irony is a lost art. Thank goodness we still have Randy Newman.

Great interview!