The first time I heard of Asleep at the Wheel was one day in Austin. I was wrapping up my years at the University of Texas, with a job waiting for me at the local daily, The Austin American-Statesman. Traffic was busy on The Drag, aka Guadalupe Street, so when I saw a large bus in my rearview, bearing down quickly on my ’66 El Camino, I went into high alert. And when I saw that logo splashed across the front – ASLEEP AT THE WHEEL – I panicked, just for a second.

Pretty soon after that I learned that the folks in that bus were a band unlike any other I’d heard around town. Their forte was something called Western Swing, an instantly appealing hybrid of country and big-band jazz. When they picked up a weekly residency in 1974, playing on the patio outside the Armadillo World Headquarters, I became a regular. Through their set list and Ray Benson’s easy, smooth stage patter, I became aware of their chief inspiration, Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, who’d pioneered that style back in the Thirties.

Intrigued, I pitched a profile on these guys for the American-Statesman. John Bustin, my boss in what was called the Amusements section of the paper, green-lighted the idea. A week or so later, I was knocking on the door of the house that the band was renting while getting situated in their new home town. Ray did most of the talking, but I also spoke with the beautiful singer/guitarist Chris O’Connell, steel guitarist Lucky Oceans and my fellow piano player, Floyd Domino.

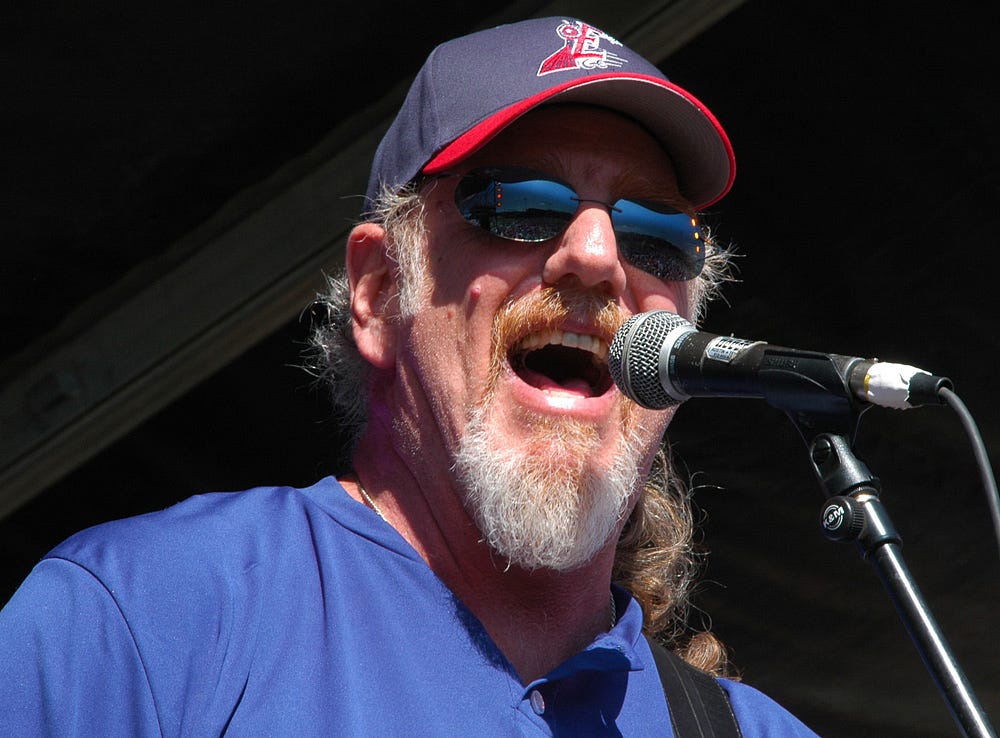

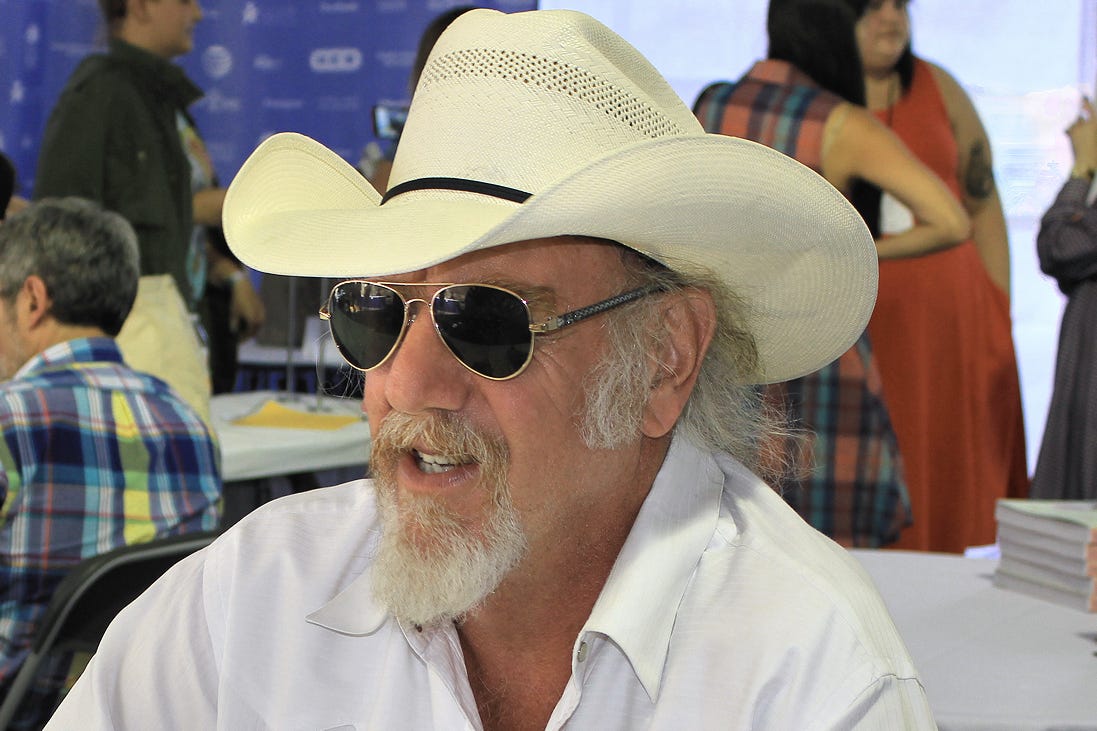

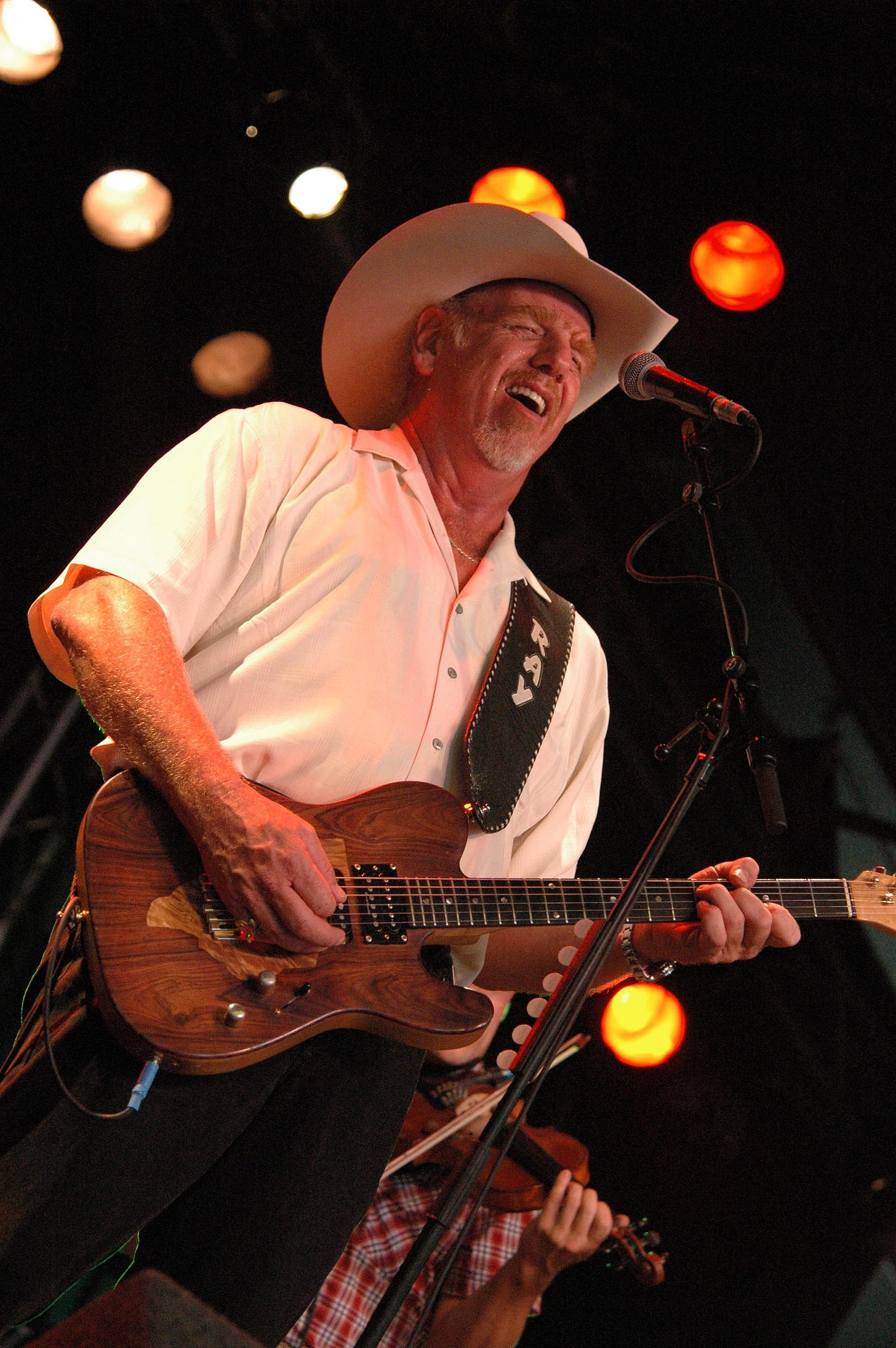

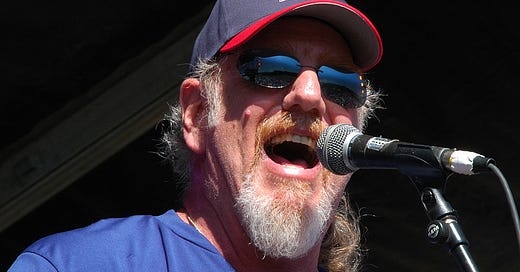

Twenty-six years later, when I interviewed Benson again, lots of talent had come and gone in the band lineup, but Benson remained at the helm. His towering frame dominateed the stage, a smile warmed his vocals. And as the final verse kicks in, his baritone boomed over the groove: “All right, now! Bring it home, boys!”

Like his stage demeanor, his references about the business now seem nostalgic. His descriptions of going from town to town evoke the nascent days of Western swing more than our own era. In particular, his opinions on how Mothers Against Drunk Driving were crimping the band’s income, though anachronistic today, reflect his perspective as a touring bandleader at that time.

One last observation: Though we spoke for probably an hour over the phone, Ray cut the interview short, apologizing that he had to pick up his son from a Little League game. It was good to know that after all that time rolling down highways, he had made time for being at home too.

****

How did a baby boomer kid in the psychedelic era wind up connecting with the kind of music you celebrate through Asleep at the Wheel?

Well, I was into the Grateful Dead and all that shit, psychedelic music, but I was also way into roots music. My heroes were guys who collected 78s and rediscovered old blues guys. That’s where the impetus was. So we started collecting old records in the Sixties. Around 1969 we got the wild idea that some of the country music stuff on the radio was lousy. I liked a lot of it, but the stuff that was missing, from bluegrass to Western swing to Moon Mullican / boogie-woogie, that was what we wanted to do, like, “Let’s try to revive that stuff.”

Where were you living when you developed your interest in roots music?

I was in Ohio, although I grew up in Pennsylvania, the suburbs of Philadelphia.

How did you even hear this kind of music at that time and place?

I don’t know! I had big ears. I played music, you know, in every form. I played in a swing band in school. I played in a marching band. When I was nine years old, I started playing folk music, so maybe that had something to do with it. I was playing professionally at that age, with a group called the 4 G’s, which was my sister, myself and two neighbors. We did very well, actually, although my parents tried to dissuade us. We were kids, but we were real good. We sang four-part harmony.

What kind of songs were you doing?

We did the Carter Family. We did Woody Guthrie. See, I went to Quaker schools; me and Bonnie Raitt have discussed this often because we both did this. So part of it was that the Quaker folks were real into roots. I went to this Quaker youth camp, and every Saturday they had a square dance, so they would recruit whoever played. I learned country music from the square dances, and I learned to love old fiddle music. I guess I was well grounded in that kind of music, growing up. As I tell my kids today, this was before cable TV: We did stuff [laughs].

You must have listened to a lot of jazz players back then too.

Oh, yeah. My older brother was into jazz, and I got way into it from him. I saw John Coltrane in 1967. The radio was wonderful back then, especially in the Philadelphia era. I got to hear the greatest jazz music you ever heard, on WHAT-FM. But I just didn’t accept the fact that there were these compartments of music, and if you liked one you had to dislike the other. I felt that there was a germ of … I don’t even know the word: art, truth, whatever, in every music. That’s what I was going for. I was way into Chicago blues stuff too. We would go down to South Street in Philadelphia and buy Elmore James records. Then I got to see Muddy Waters and all those guys, because of the festival circuits.

Do these different types of music affect how you interpret Western swing repertoire?

Well, that’s what the Western swing was all about! That’s why we latched onto it so big. Actually, there were a couple of reasons. One was, I loved Bob Dylan. He was a huge influence in the band. That kind of steered me into country and western, because he was doing all this country and western music. I mean, he was quoting sources, and I would go, “Oh, he’s into Hank Thompson, man!” Then I’d get into Hank. And Hank Williams was the other thing. Hank Williams led me to all of this, because he was a great poet and I was able to see the great beauty of country music in his simplicity. Then if you listen to Hank Williams, you notice that, of course, he was influenced by Bob Wills, because everybody was. And when we started doing Bob Wills, it was like this freedom – the ability to improvise, is what it was.

The Country Music Wasteland

What specifically bothered you about mainstream country in those days?

I think the thing that was really indicative of the time was that the Hank Williams records had all been rechanneled for stereo and overdubbed because they didn’t want them to sound old – the same thing they did with Elvis. That was heresy for us. Those were probably the greatest records of all time, the Hank Williams stuff. But what did Nashville do? They overdubbed pedal steels instead of lap steels and all that. So we felt like, “Okay, we’re gonna bring the funk back to country music.” And we really did, along with other people.

It’s kind of like coloring classic black-and-white movies.

Exactly. We really felt like, “What the hell are y’all doing? You’re ruining the legacy that you have.” Like, Ernest Tubb was one of my heroes, but they hated Ernest Tubb because he sang, quote, “out of tune.” So that was what was happening.

The other thing was sociological, which was that there was such a generation gap that when people our age played country music, they went, “Fuck you! That’s the stuff my dad listens to. And he hates me because I’ve got long hair, I smoke pot and I’m against the war. That’s what he listens to and I’m not gonna listen to him!” Then Merle Haggard confused the whole thing by coming out with “Okie from Muskogee.”

“Hippies didn’t like us because we played Merle Haggard, and rednecks didn’t like us because we had long hair.”

That was intended as a joke, though.

Well, it was. You listen to them sing “We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee,” and the guy beside the stage is laughing his head off because Merle was a known marijuana smoker. So these two things were going on. There was all this hatred between generations. We felt that the music was suffering because of that. Hippies didn’t like us because we played Merle Haggard, and rednecks didn’t like us because we had long hair.

Are you talking about when Asleep at the Wheel moved to the San Francisco area?

Well, before the Bay Area, but after that too. It was a political statement, the kind of music we made. I kept saying, “No, this ain’t right. This music is wonderful. This is incredible music. It speaks from the heart. It says everything we believe in, in terms of honesty and integrity. You’re confusing it because of the political nature of the times.”

To be fair, country music is also an easily abused form. Practically anybody in a shower can imagine being a great country singer.

There were great country singers,and there were lousy ones. It’s the same with rock & roll, which is country music, as far as I’m concerned. Rock & roll is just another limb on the tree. So, yeah, that’s true, there was plenty of schlock going on. But there always is. Shania Twain is schlock [laughs].

Roll On, Big Wheel

When did you actually start playing Bob Wills tunes?

It was actually when Asleep at the Wheel started.

But the band wasn’t founded specifically as a Western swing band.

Not at all. Bob Wills was not really in the mix. I knew who he was. I knew “San Antonio Rose.” I knew some of Hank Thompson’s music. But Hank Williams was the overriding force. That was the kind of music we were gonna do: Hank Williams and Merle Haggard. So when Haggard put out the Wills album [A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World: My Salute to Bob Wills], we went, “Oh, man! Listen!” We only had a few Bob Wills records, but when Haggard did that record, and he did it so well, I had to find a kind of music that fit all my desires. That was improvisation, the blues, the lyricism of country music and fiddle music. And that was Western swing.

What was the first lineup of Asleep at the Wheel?

It was me, [steel guitarist] Lucky Oceans and [guitarist] Leroy Preston. We conceived it at the end of ’69. I was at Antioch College. I was gonna be a filmmaker, so in January, February and March 1970 we got all our shit together, got out of school and moved down to West Virginia, to this farm that a friend of ours had. We were all songwriters too. We wanted to write our own songs.

So the band wasn’t about archiving styles of the past?

Oh, no. We wanted to recreate the music, but we wanted to do our own music too.

Was it hard to come up with new music tied into older forms?

There was no challenge. It was easy for us. It just seemed like the thing to do. I’ll tell you what, though. There was such a premium on innovation in those times – you know, Jimi Hendrix and all those guys – that I kept thinking, “You know, if you innovate just for the sake of innovation, it’s stupid.” That’s where we went. We said, “Okay, we’ll just do this.”

“Our whole thing was, ‘Let’s be the first hippies who go and play redneck gigs.’”

With only three guys in the band at first, how did you cover all the parts?

Well, we would switch off. I would play bass and drums, and Leroy would play guitar. We weren’t playing gigs, so it didn’t matter; we were just woodshedding. We had a hundred dollars each, I think, and we made it last for a few months. Then we got some gigs in Washington, D.C., and in Paw Paw [West Virginia]. Our whole thing was, “Let’s be the first hippies who go and play redneck gigs.” And we did! We would sort of fight our way out of some of those gigs; we were hippies but we weren’t necessarily pacifists [laughs].

Looking back, were the seeds of the band’s mature sound in those very early gigs?

Well, it was so funky and so … bad [laughs]. It was really weird. People recognize energy first, and we certainly had that. The reason Asleep at the Wheel has made it is that we always have entertained people. We reach the music geeks too, but the general public could give a shit about this little corner of the world that we’re exploring. So the first thing we have to do is to be entertaining.

An old guy told me, the first time I got into it, “You can’t educate from the bandstand” And I said, “No, that’s not true. You can educate from the bandstand. You just can’t preach. You can’t let ‘em know that you’re educating them. You have to entertain first." That's my first priority, to make the people dance or laugh or cry or clap.

Did you have to learn how to entertain?

No, that’s what I do. I’ve been onstage since I was nine, and I wanted to be before that.

Saying No to Van Morrison

Why did you move out to San Francisco?

Commander Cody [George Frayne IV] was a big help. When I was Antioch, they [Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen] came to the school and they stayed in my place. They were a big influence and a big help. They had us move out to the Bay Area.

What was enticing about that part of the country?

Well, Commander Cody. Dan Hicks & The Hot Licks. The scene was happening in the Bay Area. They just said, “Come on out. We’ll get you gigs.” We didn’t think we were gonna move there. We were just going out to visit for six weeks. But we wound up staying for three years.

Did Cody line up your steady gig at the Longbranch Saloon in Berkeley?

Yeah. Cody got us the Longbranch and all those things out there. He introduced us to everyone. And I knew some people out there from Antioch, like Ed Ward, the writer. Ed was my friend at Antioch, and he wound up in the Bay Area, working for Jann Wenner.

That was back when Tom Donahue was still a pioneer in Bay Area FM radio.

He had a show every week from the Record Plant in Sausalito. We did one back in ’71. We were one of his local bands. And Van Morrison was the guy who got us our record deal out there. He mentioned us in Rolling Stone and he put us on a bunch of shows. He had me up to the house and told me he wanted to produce the record. I said, “No, we need a Nashville guy.”

That took some moxie.

I know. I’ve often thought about it. But we wanted to be the first longhairs to make it in country music, so that was the right thing to do. We wanted to go to Nashville and show these guys, in their own backyard, that they were missing something. And we did. We got the right guy to do it. It was Tommy Alsup, who was in Buddy Holly’s band and was a Bob Wills guy. So it all worked to the better, because Van was learning about country music and we needed somebody who knew about it and could help us get our ideas on tape.

What was it like for a Bay Area hippie band to tackle Nashville?

The Nashville folks were, “Who the hell are these guys?” I still remember when we went to do our first sessions. We had a lap steel [guitar]. A couple of guys came around and couldn’t believe we were recording with a lap steel, because pedal steel was so dominant. But we loved it, man. We’d go there and hang out on the strip down there by the Opry [i.e., the Ryman Auditorium]. It was wonderful. We weren’t that good, but I learned how to play there. What I mean is, we’ve always been pretty good, but we never played over our heads. We always practiced hard. We worked hard on our instruments and got really good on ‘em. There were better players than us at the time, but we never played over our heads so that we sounded stupid.

Home At Last

What led you to make the move from California to Austin?

Well, we got out to the Bay Area and, of course, we starved, like everybody else. We got a gig with this guy named Stoney Edwards, backing him up. He was this black country singer who was on Capitol Records and had a few hits back then – a great singer. We wound up going on the road and backing up Freddie Hart, Connie Smith, Dickey Lee, all these guys. Now, Willie Nelson was still in Nashville then, and he was on one of those shows with Freddie Hart and Stoney Edwards; that’s where I actually met Willie. This was in ’71. He moved back to Austin that year, and after our album came out, he came down to hear us in Dallas and said, “You guys sound just like Bob Wills! You should be in Texas!” That was like, “Oh, okay. God said, ‘Come to fuckin’ Texas [laughs]’”! Even though Willie wasn’t big back then, to us he was … the Guy.

Did you play any of his songs back then?

Yeah, we used to do “Hello Walls” and “Night Life.” I had all his albums. It was one of the reasons why we had Tommy Alsup produce our album, because he had produced one of the first two albums that Willie did. And the liner notes were by Bob Wills, so we were like, “Uh, okay. This is our guy.”

I heard that Doug Sahm also played a role in convincing you to make the move.

Oh, yeah. We knew Doug because of “She’s About a Mover” with the Sir Douglas Quintet. He was a legend. And he said the same thing – of course, he said it faster and longer than Willie did [laughs]. So that convinced the band. We rented a place down here in ’73, “loaded up the bus and moved to Beverly.”

Had you established a presence there before relocating?

Well, we had played the Armadillo [World Headquarters], opening for Commander Cody. And Eddie Wilson at the Armadillo said, “God, you should be our house band!” That’s how that happened.

You were just about the only band in Austin at that time that could work one night at the Armadillo, the home base of the city’s “cosmic cowboy” country freaks, and at the Skyline Club, with its redneck clientele, the next.

Well, that was what we wanted to do. That was the whole deal. Greezy Wheels could play Soap Creek [Saloon] and the Armadillo, but we could play the Skyline Club, which was the last place Hank Williams ever played. It was so cool; that’s why we loved it. We were in Heaven, man! We came down there, 23 or 22 years old, and we were playing all the joints. See, when we were in Berkeley, we always used to complain amongst ourselves that we would play this Texas music and they didn’t know how to move. They would stand there and try to do the hippie-dippy dance, even in the Armadillo. Then here we were, and these people were two-steppin’, man! They’re waltzing! It was Heaven. For years I couldn’ believe I was getting paid; I’d just stand onstage and watch it.

Did you play differently for the hippies than you did for the rednecks?

Oh, yeah. We’d pick what we did. Some of the stuff worked and some of it didn’t.

Which was the tougher audience?

Neither one, really. This was very conscious on our part. The whole deal was, don’t hate your dad because he likes this music. There was a thing called the Old Confederate Reunion, which happened out there at Camp Ben McCullough, on the way to Dripping Springs. For a hundred years they’ve had this thing, and all the old people who were daughters or sons or grandchildren of Confederate soldiers would go camp out for a week there and have a party. All the old Confederates were dead, but the families kept doing this. They still do, in fact. It’s a social event – no cross burnings, none of that crap. I remember this guy hired us to play there in ’74. He’d brought his dad to see us over there on Sixth Street [in Austin]. He was saying, “This is great because the kids will like you and the old folks will like you!” We would do stuff like that.

How did living in Austin affect the band?

It made us a Texas band. That’s what we were trying to be, and living in Austin gave us the experiences to play those dance halls. And of course, meeting all the old Texas Playboys and [fiddler] Johnny Gimble, being able to be around them on a daily basis, and then taking it and playing these shows, having to do the “Cotton Eyed Joe” and the waltzes and the two-steps and the Ray Price stuff, that made us what we are.

Bob Wills Is Still the King

You met Bob Wills once. Did he recognize you as a kindred spirit?

I was told that, but I don’t know. He was wheeled out of the studio, we said, “Hi, Mr. Wills,” and he sort of grunted. They said, “These are the boys who are doing your music,” and he kind of grunted again. Then, that night, he went into a coma. He was on his way out, man. So I don’t know if he was cognizant. But Tommy Alsup told me that he knew who we were and he was real happy that someone was doing his music.

What did you learn from playing with people from the Texas Playboys and others of that generation?

Specifically, I learned the licks. I copped licks from Eldon [Shamblin] and Leon McAuliffe and Al Striklin and some of the more obscure guys that nobody even knows about, taking what they did and making it our own. We don’t play like they did. We are a louder band. We have rock & roll influences that we obviously utilize. But we learned the style. Sitting next to Eldon Shamblin for a number of years? That’s called a university. I learned about showmanship of that variety. More than that, we really learned how they played their music first hand: what strings they used, what amps they used. Which was very primitive, really. It wasn’t like the rock & roll guys. But still, these were the guys who invented electric instruments. Red Steagall said to me in the Seventies, “How come your Western swing records sound like real Western swing and mine don’t?” I said, “Well, you’re using Nashville guys who are using their instruments. We’re using the upright bass and a Hawaiian steel.” A pedal steel guitar sounds different from a lap steel. The modern steel will say, “But I can’t get this chord.” “Well, I don’t care. Deal with those limitations.”

There must be more than vintage gear involved in replicating that authentic sound.

Well, the first thing I always asked those guys was, “Who did you listen to?” Al Stricklin said, “Earl Hines.” So we went back to the sources. George Strait went to Bob Wills; we went to the people that Bob Wills went to. And, of course, where Bob Wills was the Elvis Presley of Western swing, Milton Brown, Cliff Bruner, Moon, Mullican, J. R. Chatwell: These were the mainstays of Western swing. You really had to go beyond Bob to get to sound like Bob.

Have you ever felt limited by being pigeonholed as a Western swing act?

Well, “limited” is a good word. That’s the other thing that we said when we started the band: We have to narrow our focus. If you narrow your focus, you’ll get more done because people can understand that better. I have a rough time doing that. My focus is so wide that if you set me free, I’ll do the stupidest things in the world – and I’ll love the hell out of ’em. But the audience don’t get it. And you do have to play for the audience; otherwise, you won’t have an audience. So, yes, it’s limiting, but it’s a very desirable kind of limiting. And if I didn’t like the music, I wouldn’t do it.

Lessons of the Road

You’ve spent much of your life in a tour bus. What role does the idea of moving play in the legacy of Asleep at the Wheel?

The main thing was that all of our idols had done that, so the road was very important. Ernest Tubb, B. B. King … everybody toured, so we knew that was something we had to do. Now, why it’s important is, for one thing, you create new fans. If you sit on your ass in Austin, you’re going to eventually burn out of fans. We would have, anyway. So we had to spread the word. Then, third of all, we loved to travel. I wanted to see the country. I wanted to be everywhere and see everything, and what a great deal it was to get paid to do this.

Then the fourth thing, and the most important thing from the musical standpoint, is that playing music on the road every night for different people is the best way to get good, due to a couple of reasons. One, you’re under a lot of stress. Two, you’re tired. Three, you’re disgusted because of this and that. It really pulls the best of you; it makes you dig deeper.

You have to develop in a way that will appeal to all markets, not just your hometown.

That’s right. And you’re an unknown quantity. People don’t know who the hell you are. You’ve got to prove yourself every night. To be honest with you, it’s a bitch. There’s nothing glorious about the road. It steels you for whatever is gonna come.

The other thing, which I’ve said to many young folks, is that the one thing you have to be able to handle, if you want to be in show business, is rejection on a daily basis. If you can’t do that, you're really in the wrong business. Going from town to town without radio play or TV, as a complete unknown, is a very humbling experience. But people in show business need humbling experiences, or you get these divas and spoiled brats. And fortunately, or unfortunately, I’ve had a lot of humbling experiences [laughs].

What kinds of venues were you playing in those early tours?

Oh, God. We played everywhere. We had great gigs, we had horrible gigs. We would play colleges; they were usually the good ones. We played honky-tonks. We played nightclubs, we played rock clus, we played country clubs, we played package shows, we played bluegrass festivals. And we got shit everywhere we went. Like, okay, Ohio: We’re booked at a rock club because “Asleep at the Wheel,” that’s a rock band,” right? We’d show up and play our shit, and they’d hate it! They’d go, “Play rock & roll!” You gotta figure it out.

“I’ve been at the breaking point a lot of times.”

But if you cut through that response, you start building your own circuit.

Yeah, and we did that the hardest way you can. That’s why there’s been such a turnover in Asleep at the Wheel. That’s why there’s been seventy-five people in the band. It’s a lot of heartbreak. I remember listening to Robbie Robertson talk about the road. He said, “It’s been ten years on the road. There’s just no more left.” And I was going, “What’s wrong with this guy?” But the truth is, it can ruin and break people. I’ve been at the breaking point a lot of times. But man, before we had that old bus, we’d get in a station wagon and a pickup truck. We’d go and play, then we’d sleep on the floor of the club or in the club owner’s house or in the car. We would have done it for nothing, just to go partying, go meet chicks. It was a lifestyle. I reckon that’s what it was all about.

Is touring less important now than it was twenty years ago?

Oh, yeah. It’s a whole different world. First of all, the big change came in the early Eighties, with Mothers Against Drunk Driving and all of that. All your Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday club gigs sort of dried up because of that whole thing. I don’t condone anybody killing people by driving drunk, but the facts are that it ruined all of that. So that was a real transition time, in the mid Eighties.

Nowadays, there’s no development grounds. Young kids have to be stage-ready in a different way. It’s a shorter ride, you know? You’re learning from a video. You ape that guy. Then you’re onstage. Then, boom, you have a record, you have a video and you make it, as opposed to learning how to work a crowd.

How do you keep from just “phoning your parts in” when you’re doing hundreds of nights each year, decade after decade?

When it becomes that way, I’m not gonna do it anymore, unless I’m getting paid so much money I can’t stand it. But I can make money a whole lot of other ways. I just love doin’ it. Playing the music is never a problem for me. There's no problem doing the old stuff or coming up with new stuff. I love it as much as I did the first time I did it; otherwise, I couldn’t get up there and smile. The only thing that’s a problem with me is the logistics and the finances; that’s the stuff that drives me nuts.

Surviving Garth Brooks

So why did you take over business management for the band in the mid Eighties, after leaving it to others up to then?

Well, I was paying a manager between fifteen and twenty percent a year, and losing about that much. And I always seemed to be in a snit with somebody. I’m a pretty good businessman. I know what I’m doing. So I decided to do it, just like I did with producing. I said, “I’m gonna be a producer now.” “Well, you can’t be a producer!” I said, “Oh, yeah? Watch!” That’s what you have to do in the music business. My job is to wake up every day and try to figure out what the hell I’m gonna do and how the hell I’m gonna pay all these bills and what my next project is gonna be. I wouldn’t do anything else, unless I’m forced to.

Taking on that kind of work also gives you a higher level of confidence.

Yeah. Once you’ve faced the Devil, man, it’s like, “Big deal, dude!” The other thing is, I realized that I knew more. I had this experience under my belt. And experience is the best teacher. I was able to make my own deals. I didn’t need a mouthpiece. I didn’t need somebody to interpret what I wanted to businessmen. I could talk to ’em myself. It’s a rare commodity, I’ll be honest with you. I don’t know many artists who can do it, because it’s a whole ’nother part of your brain. You also have to have that thing, where you’re not so full of yourself that you’re a diva and an asshole, which most musicians are, to be honest with.

Garth Brooks is a model for artists who want to manage their own business affairs.

He’s a megalomaniac.

A lot of artists weren’t happy with how he steered the resources of Capitol Nashville to his own career.

We were there, man. It was awful. The World According to Garth: If you didn’t fit into the plan, you were out.

But you’ve recorded with Garth. Was he a different kind of guy back then?

No, he was always like that. He’s a control freak. And you know what? If I sold ninety million records, maybe I’d be that way too. I don’t know. He’s a very generous guy to the people around him. On the other hand, he’s ruthless. The shame of it is that I really like his early music. He did some brilliant work. I don’t think he’s done anything like it in the past couple of years.

Does the rise of Garth Brooks signal a return to the star-driven commercialism of country music that Asleep at the Wheel battled back in its early years?

Yeah. Country music is funny. I mean, take an artist like Tim McGraw. I’m not a fan of most of Tim’s stuff, but his last record [A Place in the Sun, 1999] is one of the best country records I’ve ever heard, with that Rodney Crowell tune, “Please Remember Me.” They have a capacity to do great stuff.

On the other hand, Tim wouldn’t be where he is if he hadn’t done “Indian Outlaw,” which in my opinion is kind of a stupid song. But it was a huge hit.

This seems especially wrong in country music because of the honesty the genre is supposed to represent.

Well, yeah. I have mixed feelings about the schooling of country music. What did Waylon Jennings say about Dwight Yoakam? “You know what he needs? He needs a drinkin’ problem [laughs].”

Phases & Stages

Can you divide Asleep at the Wheel into different periods, as one might divide the history of the Duke Ellington band according to its personnel changes?

Oh, yeah. There was the first band, which went up to about ’74. Then there was the hip band, which was ’74 to ’78. Then there was the Lost Boys band, late Seventies to early Eighties. You know, there were some things about Asleep at the Wheel that people don’t know, like Jimmie Vaughan’s first appearance on a record was on our live album in 1979 [Served Live]. Big deal, but we were into blues. We were doing different stuff. [Harmonica player] John Nicholas ws in the band, so I had Jimmie come in. Then I had [vocalist] Maryann Price from Dan Hicks & The Hot Licks – the Two-Girl Band, I call that. Then, from ’81 to ’85, it was a struggle. We didn’t have a record deal. Disco was happening. Luckily, I was making a living doing these Budweiser commercials. We were still touring, about 120 days a year, but it was pretty dismal.

The audiences were shrinking?

Oh, yeah. They were, like, nonexistent. It was awful. But every week somebody would come up and say, “Don’t quit! You guys are the best!” We’d have one good gig a week on the road. Then around ’85 or ’86, we put the band together that I feel was the comeback band. Larry Franklin was the fiddler; he’s now the top Nashville session guy. We started working a lot. We had the right guys. We were back on Epic, and we had some hits with “House of Blue Lights” and “Way Down Texas Way.” Then, boom, we were back, man. It was amazing.

Then it started changing. Larry left. We did that live album in 1991 [Live & Kickin’: Greatest Hits]. Then I did the Bob Wills tribute album [Tribute to Bob Wills & the Texas Playboys], and that sort of evolved into this band. Of course, about seven years ago, Cindy [Cashdollar, steel guitarist] joined the band, and it changed again. Jason [Roberts, fiddler] came in, and we now have the modern band. I guess those are the periods, as I see them.

Was road burnout always the reason why people left the band. Were there any personal disputes?

There was that too, yeah. But nobody hates anybody. Our whole thing is, learn what the guy did before you. Learn it well. then give it your personality.

“Once you’re in Asleep at the Wheel, you’re always in Asleep at the Wheel.”

Do you have an ideal Asleep at the Wheel lineup in your mind?

Yeah, but I can’t say who’s in it [laughs]. I gotta work, you know? But it’s funny. It’s like saying, “Who’s your favorite kid?” No, I don’t have a favorite. It’s really about personalities. That’s why I did all those [reunion] albums, to get everybody back. Once you’re in Asleep at the Wheel, you’re always in Asleep at the Wheel. It’s just a time contingent we’re dealing with.

Does it rejuvenate you to bring back your old colleagues for reunion projects?

Well, I actually wind up remembering how it was and I go, “God, I’m glad those days are over [laughs].” All the angst, all the bullshit. The good things were good, the bad things were bad. All it really gives me is perspective. That’s what I’m searching for these days. That’s the beauty of aging.

Perspective in what sense?

In how we approach the music and where we fit in. What I did with the Bob Wills album was, I looked at thirty years. I went, “Okay, Bob Wills, 1934 to 1964. Shit, he was out of business in 1964!” That’s amazing. That put it all in perspective for me to appreciate the fact that we’re still here, appreciate the fact that we’re still doing it, appreciate the fact that we have a lot to do still. That enables me to go, “Okay, we’ve done something very real, very lasting and very real. And it ain’t over.”

####

Another great, enlightening interview...

That was swinging Robert,thanks l.c. smith Gibsons BC