You would think there’s nothing easier than to put a microphone in front of somebody and ask them to talk about themselves. Actually, it can be a challenge: They can be monosyllabic, suspicious or even hostile. They can just barely be awake, an experience I had one early morning with Bruce Springsteen and late one night with Stevie Wonder. They can drone on and on about how great they are without letting you pop in a question or two. Or they can be just plain crazy.

This is why I always enjoyed interviewing people about someone other than themselves. The occasion might be joyful: induction into a hall of fame, perhaps. More often it’s solemn, just after someone’s passing. In that situation, they know they can’t be rude – although, if they are, that can actually be gold. They also can’t be on autopilot; they have to actually think about who their departed colleague was and why they’re important. Of course, the interviewer has to be present and attentive, as in any such situation. And they have to have done their homework.

I was ready on all fronts when my brother Andy Doerschuk, then editor and co-publisher of Traps, assigned me to profile the late Al Jackson Jr. If you’ve heard any of the classic R&B recordings issued by the Stax and Volt labels in the the Sixties, you’ve heard him; he’s the drummer with the infallible tempo and the wisdom to know that when you play less, you can lock in more effectively with your fellow musicians so that when you do add something simple its impact is maximized.

That last point became obvious to me from the first time I heard Sam & Dave’s “Hold On, I’m Comin’”. The spotlight was on the vocals; to my ears, Sam Moore burned brighter in the spotlight, with his gut-deep soul and exuberant ad libs. But the drumming was, for me, the key: tight, spare, relentless and, in that one fill that Jackson allowed himself to segue from the last chorus into the fade, explosive.

Researching this story was like attending a high school reunion: familiar, sentimental, inspiring. Tracking down and speaking with participants from the Stax/Volt heyday was trickier, though I always enjoyed doing that sort of detective work. I actually met Wayne Jackson, trumpeter with the Stax studio band, in the popcorn line at Nashville’s Green Hills Theater complex. I think that encounter was what gave me the idea to pitch Andy on this story. Wayne agreed to participate when I asked him to share his recollections of the era, though he had one stipulation: I had to buy him lunch at the Sportsman’s Grille in Bellevue. Despite the consensus that true journalists didn’t pay for interviews, I figured what the heck, it’s only a burger. Besides, I liked the Grille; turning a meal into a tax writeoff posed no conflict for me.

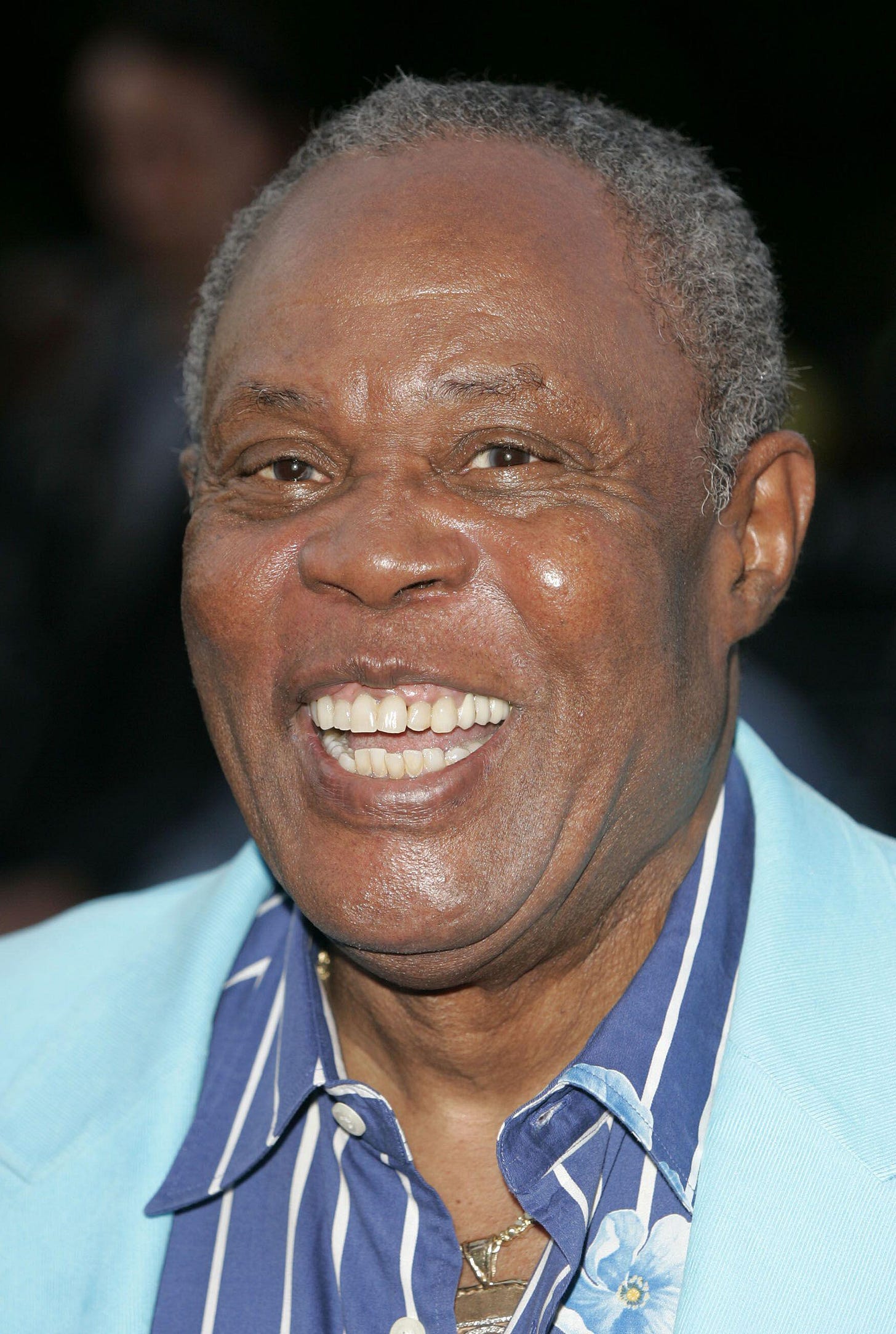

Moore, on the other hand, was thrilled to hear about his project. He was onboard immediately. In fact, I believe I would have had to tie him up to have kept him from talking. His conversation was nearly as exhilarating as his singing on “Soul Man,” “I Thank You,” “When Something Is Wrong with My Baby,” “You Got Me Hummin’” and “Hold On, I’m Comin’”. I don’t remember any conversation, much less an interview, that left me feeling as positive as this one. Like Jackson, he is irreplaceable.

****

What is the most important thing to know about Al’s drumming?

That’s a good question. If I had an answer I’d be real quick with it. But of all the times I was at Stax studios and saw this man playing, I don’t know what made him special. I guess it was just talent. We can put him in the same bag with Ray Charles or Billy Preston or any of these musicians. He was in a class of his own. I don’t know of anyone that I’ve come across through the years that wouldn’t say stuff like this: “You know, Al Jackson, I learned from listening to him.” I’m still amazed today at how great this man really was? I’ll just give it to you straight.

You’re the first person I’ve spoken with who has sung with Al. Can you describe the experience of singing over his rhythm?

Al could lay down a pattern, and he would follow you wherever you wanted to go. Let’s go back to “Soothe Me”: It wasn’t anything rehearsed with him. He was spontaneous on the stage. I was talking to him, and I set it up to the point that, “Any time you’re ready, Al, you do what you’ve got to do. I’ll catch up” – all this ad libbing. And look how this band brought it out! Come on, Bob! This man was like a human metronome. He had tempo. It didn’t matter where you went with him, he could hold you right in the pocket. And I’m going to tell you, even in my band from way back, I’ll say, “Can you do this? Can you lay that down?” And they’ll go, “Hey, man, I’ve been trying to do that for years by listening to Al. I’ll do the best I can.” And you go, “Yes, do the best you can. Don’t try to be Al, because you can’t be. There’s only one Al Jackson.” I’ve seen a lot of guys blow it because they try to do it like Al. You can’t do what Al was doing! Nobody can be a Billy Preston, a Ray Charles, a Duke Ellington, or a Count Basie. His father played jazz, and his son could really play jazz, but he comes in there and plays on something we were doing. Duck [bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn] and Al: The pattern those guys could lay down! You’d go, whoa! Go back to the old stuff that Sam & Dave did. Go back to the stuff that Otis Redding did. Go back to the stuff he did at Hi [Records] with Al Green. You still got nobody who can do it like Al did it.

Al Green didn’t record on Stax, so not too many people know Jackson played on those sessions.

Al Green did good stuff. I don’t mean any harm; I don’t think it takes anything away from him. But the chemistry [with Jackson] wasn’t there.

Fills & Frills

Talk about that snare fill going into the ride toward the fadeout on “Hold On I’m Comin’.” That captures the simplicity of his drumming as well as his knowledge of where to drop that rare fill.

That was what Al brought to the table when he played those drums. He’s the first drummer I ever heard play his snare and cross over and put his foot on his foot pedal! I’d never seen that before! I swear to God! Now, he’s not playing the sock. He’s got his foot on the sock, holding it down, and he’s playing the snare with one hand, and he’s beating with the tempo on the sock! I’d never heard any shit like that! It’s what he brought to the table. He made you better than you were! I’m telling you the truth! If you went in there saying, “I’m good,” he made you better than good.

Could you elaborate on that thing of playing the snare and the kick and the hi-hat?

Okay, the bass drum … Now, understand, in those days we were recording on eight-tracks.

You had one microphone on the drums.

Right! He would step on his sock with his left foot and under, with his right hand, he could play the snare. He played wrong! Most drummers hold the stick between the middle finger and the upper finger. He played … I don’t know how to put it. He didn’t have a style. He played like he was throwing a knife. You’d have to see it in your mind: Oh, man, what is this guy doing? And he’d look at you and laugh. A lot of times, Isaac [Hayes] would leave it up to Al to find the tempo. Al was always the one who would set the tempo. He would ask Isaac what he wanted, and then he’d say, “Let me try this.” Maybe the first time it wasn’t heavy enough. Maybe it was too light. But he would work it until he got it. He’d say, “Okay, let’s go.” Isaac would say, “Count it off.” He’d count it off, and you’d go, “Holy shit! That’s it! That’s it right there!” And Duck and Isaac, and if you want to say [guitarist Steve] Cropper, okay, fine: That was the chemistry to Sam & Dave, Otis Redding, Al Green, the Staple Singers …

And they also did “In the Midnight Hour” with Wilson Pickett.

You’re right. Thank you, he did. I’ve stood in front of some good drummers. If there’s one thing I do know, I know drummers, but I know them because of Al Jackson. I learned by watching how he played. He’d say, “Where do you want to go, Sam?” “Well, I don’t want it to drag, Al.” “Okay.” Listen how he’s doing [sings]: “Oh, she may be weary …” [from Otis Redding’s “Try a Little Tenderness”] He wouldn’t stop and change the tempo. He would play through that slow tempo and he never missed a beat. The tempos change, but you had to pay attention. After Otis did that, I was listening to it with Otis, and he’s doing that [Moore imitates Redding’s gobbling ad-libs toward the end], and that guy is catching it! Shit! I only know one person today who would be able to do that, and that’s a young man in Memphis by the name of James Robertson. He was playing with Isaac. He’s the only one I know that comes closer to Al Jackson than anyone I’ve heard in a long time. But other than that, if you’re talking about Al, I don’t know if anyone could do the things that Al Jackson could do.

“He Was So Cocky …”

“Soul Man” just doesn’t pop on the Blues Brothers cover the way it does on your original version. When Al kicks into the beat with that little roll into the beat …

It’s right into the beat!

Cropper is doing double-time on guitar, but Al is holding it down to regular time. How did that rhythm feel come about?

They had already cut a rhythm track when I came into that session. You’ve got to understand: A lot of the stuff they were playing at that time had a country flavor to it. Now, we rehearsed it [unintelligible]. “Tonight, when you guys come in, we’re going to lay the vocal.” I’m listening to Isaac play it and I’m going, “No, I’ve got a problem with this laying that beat down.” I went up into the engineering room and was sitting with Jim Stewart. Isaac said, “Okay, put it on, so Sam & Dave can listen.” I listened and I went … “What? Wait a minute!” It didn’t have a sanctified beat. It didn’t have a rhythm & blues beat. It had a pop beat. It wasn’t dragging …

It kind of strutted.

I like that! I like that, Bob! It strutted! You just gave me the adjective: Al Jackson was a strutter on drums. It’s just like a football player, like Emmett Smith and all these people, when they’d come up: They’d run, and they’d pick up so many yards, and when they came out, they had a strut walk. Well, when we’d get through the rhythm, Al would get up – I’m not lying to you – and come into the engineer’s room. He may stay there two or maybe three minutes, maybe five minutes. Very seldom would he say, “We want to work on this a little more.” Most times they would turn to him and say, “How do you like it, Al?” And he would go, “How do y’all like it [laughs]?” It was like, “I done my job.” He was so cocky … but he was so goddamn good.

He knew he was good.

That’s it! He knew it! He’d walk in with that head cocked to the side. He wasn’t that tall, but he was nice looking. He could look at you, and if you didn’t know what you were doing, he was like, “You better get your shit together because I’m getting ready to put something up your butt!” He could make shit smell good [laughs]. He did know he was good!

He was a little older than most of the guys at Stax, so maybe he was kind of a mentor.

Al wasn’t the first drummer to play with Dave and me. There was another guy. I can’t remember his name, but I liked that drummer. I said, “Whoa! He’s good!” We had [Mabon] “Teenie” Hodges [a guitarist] and all that stuff. After a couple of times, he wasn’t at Stax any longer. He didn’t get fired; they just said they were bringing in another drummer. I was like, “Oh, man. This guy here, he’s damn good.” When I first saw Al, he had that cocky look on his face. He was quick with a joke. But you could look at him and think, “Man, I better know what I’m doing with this guy, ‘cause this guy ain’t nothin’ but playing with him!” Al’s thing was, “It’s up to you, what you want to bring to the table. I’m gonna give you what I have to do, but it’s up to you to focus. I’m gonna help you sell the damn thing, if you want to record.” That’s the way Al Jackson was. I tell you, man, if he was playing the drums he’d gotten an endorsement from, can you imagine what kind of a drummer he would be. I mean, even these drum machines tried to copy Al! I’ll tell you the truth, I’ve had guys tell me, “I listened to the old stuff that you and them did. I computed them into Al.” And I said, “What?” And guess what? It didn’t come out right. It was okay, but it was not Al Jackson’s heart.

You nailed most of these records in one or two takes.

Well, when we did “When Something Is Wrong with My Baby,” no lie, Bob, it took sixty-five takes. Dave was ahead of the beat. Then, when he thought he had it, he would say, “You’re ahead, Dave. Back it up. Now you’re behind. Okay, Dave, are you counting?” You don’t count! Al is doing that for you! Al has got you! [There’s plenty of musical gibberish here.] Dave is taking a breath instead of being right on the beat. If he was on the beat, he’d have it.

A ballad beat can slip away from you.

It can! He was so good at holding you in tight. You could jump all over the damn place if you wanted to. Listen at “I Take What I Want,” “You Don’t Know Like I Know,” “Wrap It Up” …

“The records that Sam & Dave were recording were way ahead of their time.”

He opens the hi-hat on “You Don’t Know.”

He does! [There’s more exuberant gibberish.] He’s playing the hi-hat! The records that Sam & Dave were recording were way ahead of their time. Today, when you go back and listen, it’s true, because can’t nobody play it! You’re not going to hear anybody on the Idol that Stax was doing. You know why? They can’t do it. I just want to be honest with you, Bob. I don’t want to put that kind of pressure on anybody, because there’s only one Al Jackson. They’re scared to tackle that [Stax] stuff. You ain’t gonna find nobody to tackle that stuff. Oh, sure, they’ll tackle Otis Redding, but there’s always something taken away. I’ve heard that boy Taylor Hicks sing “oh, she may be weary,” and when the tempo changed I’m going, “Uh-oh, he lost it.”

Did Sam & Dave, like Otis, do material much faster onstage than in the studio?

We were rehearsing a new song that we had out. I remember we were in England. At that time we didn’t have charts because we’d go by the record. And it took us all day long. The drummer couldn’t get it. He could stay in tempo, but he was listening to stuff he didn’t have to listen to. Actually, Al was really simple. He didn’t do nothing fancy.

But he did subtle stuff. You can listen to Buddy Rich blow at full blast for twenty minutes, but Al got the same effect with one snare hit.

I was telling the guys, “Fellas, you’re making it hard for yourself. What you’re listening to isn’t hard; you’re making it hard. You’re listening to something that’s not even there!” It’s a simple beat. All you’ve got to do is count it off, don’t do nothing fancy, and stay in the pocket.”

“He was the best setup man you’ll ever find.”

His kick patterns were especially effective.

Weren’t they? I’m pretty sure he was on the ball of that front foot. The way he could triple it … Buddy Rich played double bass. Al played single. And Al sounded like he was playing double [laughs]. He had one single mic on the drums. Today the drummer’s got to have this and that and trigger off of this. I’ve since found out that even with guys who use the click, they try to do something that’s not there and they can’t get it when the click falls in. Hey, you can play to the click, and then it falls to live. You’ve just got to listen. Stop thinking. Just count it off and stay in the pocket. Now, I tried to speed it up onstage, but the guys just couldn’t do it. Just keep it in the pocket – and watch what the artist is doing. Never take your eyes off of his feet. Now, there were two of us, so in the live show the drummer had a problem because he had to watch both of our feet. So I got to a drummer, and still they were going, “Where do you want me to come in? Al is going …” “Stop worrying about what Al plays! Al is playing subtle, and you’re trying to play like Buddy Rich!” He would kick the hell out of you! Now, if you wanted to put on a show, he’d help you put on a show. Oh, my God, you should have been around when we went to Europe and did the Stax/Volt II. Man! The things this guy could do! When I’d leave the stage, I’d be so tired [laughs]. And he would be tired! And if you get Al Jackson tired, you know you’re doing your job. He would go, “Sambo! You’re trying to get me tonight! Tomorrow night I’m gonna lay something in your butt [laughs]!” He’s going to put his foot all the way up to your tonsils. He’s going to whip the hell out of you up there. If you bring that tempo [unintelligible] breathing, he ain’t gonna let you come out of there. He’d be back there, saying “Work the song! Work it! Come on, Sam! Work it! Do what you do, ‘cause I got you back here. Wherever you go, I’m going to take you there.” He was the best setup man you could ever find. He’d set you up to the point you could talk [i.e., to the audience]. It feels so good [unintelligible], and Al would look at me and smile. You know what he’s doing? He’s bringing up the tempo. It’s like how we did “Soothe Me”: When I say, “Are you ready,” he’s like a machine gun. [Moore articulates a rapid snare lead-in.]

“He didn’t hang out with us that much. … Basically, Al came in to go to work.”

What kind of a guy was he to hang out with away from the stage?

Al had a circle. If he allowed you to get into that circle with him … He was a very complex man to know, but if he liked you and felt comfortable with you, you couldn’t find a better friend. Nine times out of ten he’d be very cordial and professional, and that was about it. He was just that way. He didn’t hang out with us that much. He hung out with Duck. Basically, Al came in to go to work. When Al left in his Cadillac, that was it. He was real cocky, like I said. He was hard to really know. But once he let you in, the door was open to you.

You had to earn his friendship.

You really did. You had to show him why he should let you be part of his circle. He was just that way. You accepted that or you didn’t; it didn’t bother him. If you didn’t carry yourself professionally and act like a gentleman, he did not bother with you. You had to carry yourself like a professional around him. And you had to do your job, because he’s going to do his for you.

What did his death mean?

I think I was in New York when I heard about it. It felt like my whole thing was dug out from under me. Since then, with Booker T and all that stuff, not to have him around, he was just missed. I liked him. I believe he liked me as well, because I was one of his buddies. But, man, I miss this guy. He was first, Duck was second, Isaac Hayes was third … Al and Isaac, that was the sound of Sam & Dave and Otis Redding. It was raw, rough, and gritty. We had a lot of guts. We knew what we had to do. A lot of times, they’d say, “Duck, stop trying to compete with Motown! You can’t do that. Al would say it many times: “Hey, man, let’s stop trying to compete with that rhythm section at Motown because, hey, you can’t do that. Berry’s got another vision for those guys. Let’s stick to our vision.” That’s how it worked out.

Those Motown records were about selling a dream to the audience. Stax was about real life.

Yes, absolutely, my friend! From Japan to Hawaii to Italy, people who know the work of Stax always find somebody to say, “Al Jackson.” You know how that makes me feel to know that this guy was part of my life and my career? Everybody wanted to do it like Al. I was honored, and I don’t care how long I’m doing this, I shall never forget that guy. He made Sam & Dave, Otis, and all of us better than we really were.

####

It's funny, yesterday I'd just happened to play Al Green's "Love and Happiness" just before this dynamite interview hit my inbox.

I'd never really given much thought on the chemistry (or lack thereof) between Rev. Green & Mr. Jackson, so I did a replay and could kinda see what Sam was getting at. That dynamic that was overwhelmingly present if he and Dave or Otis was on the mic wasn't quite there. But DAMN was Al Jackson locked in with all those Hodges!

Gonna have to do some more close listening - good thing it's a long weekend.