One day about eighteen years ago, Mike Meade and I stood together in some withering summer heat. We were an hour outside of Nashville, in a vast flat space reminiscent of Hollywood western settings. Normally, I don’t feel drawn toward dust and desolation. But on that afternoon, I was exactly where I wanted to be: outside a small corral, watching miracles happen.

Sam Powell, renowned in equestrian circles as a horse whisperer, watched as a client led her Palomino into the space. The horse was skittish, putting against the reins its owner held. Sam listened as she admitted that she could not calm the animal; after every attempt, a battle of wills surfaced between them, which led moments later to another abandoned effort. Could he do anything to help her deal with this?

Sam, squinting into the sun, promised to try. Motioning her toward the exit, he approached the horse and put both hands around its face. He said something too softly for any nearby humans to hear, but they did visibly calm the animal.

Seconds later, in one graceful motion, he swung himself up onto the saddle, and the two began a leisurely trot along the corral fence. “He’s taking the horse back and forth, loosening him to make him more flexible,” Mike whispered. “Now he’s taking her sideways. They’ll stop and go forward. He’s keeping her mind focused on what she’s supposed to be doing instead of paying attention to everyone else.”

“He’s using his own weight to lean the horse into the opposite direction,” I observed. “A lot of this is about giving the horse a sense of trust before he begins …”

“Yes,” Mike confirmed. “He’s trying to gain her trust throughout the whole procedure. He’s not abusing her or beating on her. He’s being very gentle. He’s making the horse want to do it.”

Now, I am about as far from a cowboy as one can be. I took one riding lesson in high school and quit almost immediately when instructed to dig my spurs into the poor beast’s ribs. But I do know when something strange happens in front of me. And that was enough to pique my curiosity – the essential first step toward doing a successful interview.

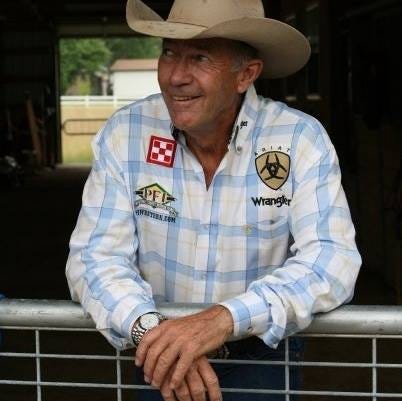

Mike, who was and continues to be Sam’s assistant, was my contact when Kat Atwood assigned me to profile this extraordinary individual for Music City News. I had no idea until that night, when I drove home from Sam’s ranch, that this weather-beaten, part-Cherokee trainer was also a philosopher, whose thoughts on working with horses informed his wisdom about deeper issues of existence and even eternity.

I’ve never learned more from any interview than I did that day with Sam. I sensed then, and I believe today, that some sort of magic was embedded in his DNA. We spoke for hours, every minute of them widening my own imagination. Which is why I’m doing something new here: Because my transcript of our conversation is both long and substantive, it’s going to run here in segments. Every two or three weeks I’ll post the next until it’s all (or nearly all) here for you. Please dig into it; I think you’ll feel some of the wonder I still have for Sam Powell.

***

Let’s start at the beginning. Tell me about your childhood and how it steered you toward who you are today?

I lived mostly with my grandparents – my mother’s parents or my daddy’s parents. I shifted back and forth. I lived with a lot of aunts and uncles and different people. My parents had divorced when I was a year old. My dad has asthma really bad and he had to move to a dry climate to survive, so he took me and my mother with him to California. But my mother couldn’t stand it, so I guess I was a year old when she brought me back to Oklahoma to live with her parents. That’s where I grew up. I went from one grandparent through aunts and uncles, one thing or another. When she got remarried, I was probably ten or eleven years old. She had a daughter with my stepfather, and that was a priority in her life. I wanted to be a cowboy for some reason. I don’t know why. It wasn’t the most popular thing in the fifties to be a cowboy. Everybody else had ducktails.

Well, there were cowboy shows on TV.

I wasn’t into TV. Nobody I knew had a television when I was growing up. But I’d go to the movies on Saturdays and watch Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, and all that. I don’t really know what whetted my thirst for the cowboy lifestyle. It was just something I wanted to do. I started paying ten dollars for the entry fee to ride in some rodeos and then fifty dollars for something else.

My dad’s parents, who I was living with for a little bit, kept telling me that he was a great horseman who lived in Arizona. Dad had a position with a private school in Scottsdale that boarded from the fifth through the twelfth grades. All the rich people from Palm Springs and Los Angeles would send their kids to this boarding school. They had 150 head of horses because riding was part of the curriculum. They had show jumpers, they had roping, they had English riding, and Dad’s job was to teach that part of it. They had football and baseball teams and everything else, but the equestrian part of it was a big part of that boarding school. My grandparents told me that. Now, I’d never seen my dad, never had a chance to meet him, so I decided I wanted to get acquainted with him. I think I was fifteen or sixteen when I saved up my money, got on a Greyhound bus, and went to Phoenix. I got off the bus, got on the telephone, and called him, and he came to the bus station and picked me up.

Was this a visit, or were you planning to move out there?

I just wanted to meet him. I didn’t have any plans when I got there. I wanted to see what he looked like. I didn’t even know if he’d come and pick me up. But he did, and when he walked in the bus station in Phoenix, I knew him right away. There was something there. We drove around. He took me out to the school. I met his wife. He had two kids and I met them. I stayed out there probably a month. He put me on a bus and sent me back to Oklahoma. I got to be sixteen or seventeen.

I had a car, a ’49 Ford. I think I had twenty dollars in my pocket, and I drove that Ford back to Phoenix. It took me three days. This was before the days of interstates. I’d sleep in the car at night and drive the next day. I got out there and spent four or five months with him. He tried really hard to teach me his philosophy on horses, but at that time I was kind of bull-headed and full of myself. I didn’t really listen, as I should have. But I told him I wanted to train horses, and he really wanted me to go with a town job someplace. He felt that was a better future than being a cowboy.

The Rodeo Wanderers

When I was a sophomore I quit high school, took off and went to rodeos. I’d work on ranches whenever I could find a job for a month or two or three, whatever they needed. As soon as I got some money saved up, I went back to do rodeos again. I really enjoyed it. I traveled all over with four or five friends; we loaded up the old car and drove around the country from one rodeo to the next. We had no money. We’d have to pool everything we had to fill the car up with gas. We had no money to eat on. We’d be down in south Texas or someplace on a weekend, driving to a town. We’d come across one of those city parks, and there’d be a banner reunion going on, with two hundred people standing there, playing badminton and throwing horseshoes. We’d just park the car and join in.

We had a friend who traveled with us. He was the greatest. He could wade into a bunch of people and know everybody’s name within five minutes and be carrying on a conversation like he was born there. We’d always send him in first, to run interference. When they started eating, we’d get in line and eat with him. Nobody knew who they were, but at a banner reunion they usually wouldn’t admit they didn’t know you. They’d always make you feel comfortable. You could hear a name or two about Fred or somebody from his cousins: “You look a lot like Fred.” First thing you know, they’d not only feed you, they’d pack a box of food to take with you. We’d go down the road, and maybe three nights later we’d come to a motel that said “Free Continental Breakfast.” We’d park in the lot and sleep in the car. At six o’clock we’d go in the lobby, eat donuts and drink orange juice, and fill up again.

“I was riding bulls at sixteen or seventeen years old.”

Were you working at those rodeos or just going to them?

I was riding bulls at sixteen or seventeen years old.

How do you get on top of a bull at age sixteen?

I don’t know. There’d be a little town in Oklahoma having a rodeo. I’d borrow the bull roping equipment and say, “I’m going to try that one time.” I managed to get him rode. I didn’t win any money but I thought it was pretty easy, so the next weekend I bought my own equipment, found another rodeo, and got bucked off. I didn’t do so good, but I found out it didn’t kill me, so I’d do some more. I kept going to the little rodeos until it dawned on me: The big rodeos paid a lot more money. The ground wasn’t any harder. So we’d go to Cheyenne’s Frontier Days or Calgary’s Stampede, all the big rodeos. We might win good money and then, being young people, we’d blow it all and in two or three weeks we’d be broke again.

Back in those days, vagrancy was a big thing. They didn’t make heroes out of homeless people; they threw you in jail. You had to either have money in your pocket or means of support. We’d get in some of those towns and run out of money, trying to go from one rodeo to another. We’d always stop at the local police station and tell them, “We’ve been to the rodeo. We got bucked off. We didn’t have very good luck. We’re broke.” A lot of times they’d let us sleep in the jail and eat fried baloney sandwiches with the inmates. They’d rather have us there than carousing around town with no money. They’d usually find a job somewhere at a filling station or washing dishes for two or three days, to make enough money to get out of town. They were good about that out west. Now, we weren’t east of the Mississippi that much; we pretty much stayed in the western part.

Then I got a job on a ranch down in southeast Oklahoma. The man paid me seventy-five dollars a month and put me on three thousand acres to look after three hundred head of cattle. I started on the first of November. I was supposed to feed them during the winter and help them until April or May. I lived in a three-room shack in the middle of nowhere. They brought me groceries every week, so I never went to town. I never left that place that whole winter. His wife would come every so often and cut my hair with the horse clippers. I never drew a paycheck. I didn’t need it. I drew it all in one lump sum at the end of the deal, for seventy-five dollars a month.

But I went back to eastern Oklahoma and met my wife-to-be. We started dating a little bit more and ended up getting married. I got a job on another ranch and took her with me. That time, though, I got to a hundred dollars a month. We had two daughters. When my second daughter was born, we were living on a ranch about ten miles from town.

My wife told me we needed to go to the doctor in town. I loaded her up in a truck at ten o’clock at night and went to the town doctor’s house and knocked on his door and told him my wife was getting ready to have a baby. He gave me the keys to the office and said, “Go down and turn the lights on. I’ll be there when I get dressed.” We drove down, I unlocked the door and turned the lights on, he came walking in, and he told me to turn the TV on because Johnny Carson was on. We turned the TV on, he had my wife go back in the back, and we watched Johnny Carson for fifteen or twenty minutes before he said, “I’d better go check on your wife …”

After she’d given birth, the doctor said, ”Just rest another hour and then we’ll take you home. Just turn the lights out and lock it up when you leave.” And he left. We got there a little before ten and I had her back home about twelve-thirty with the baby. It cost me a hundred dollars, that nine months pregnancy, to get the baby delivered.

Anyway, we kept working on the ranches. She helped me a lot. She was another hired hand, so they got a two-for-one deal. We’d be out feeding cattle and hauling hay with those two little girls she had in the truck in the middle of the wintertime. And I was still trying to go to rodeos and make extra money, pick up a few bucks on the weekend so we’d have a little change and buy a little better car.

We moved back to the northeast in Oklahoma back in ’67. I went to work for the federal government as a livestock inspector and stayed there for a year and a half. When I went to work for the government, I didn’t have a high school education. You can’t do a civil service job without a high school education. So I studied for that and got my GED in order to take my civil service test. You were supposed to have two years of college, but I passed the fundamentals and got my civil service desk. If I’d been smart, I would have kept it and I could have retired twenty years ago. But I decided government employment is not my cup of tea. I’d work eight hours in the field and do ten hours of bookwork when I got home. So I quit that. My wife wanted me to get a town job, so I worked there for three or four years. I worked nights so I could still go out and cowboy on ranches during the day. I had a chance in 1970, I guess, to go to work on the ranch I stayed on for twenty-two years.

Which ranch was that?

It was called the Cross Bell Ranch. It was beautiful – 134,000 acres. When I went to work there, they’d had some personal problems. The boy that was running it had been murdered [E. C. Mullendore, in 1970, in a case yet to be solved] so things got a little tough. Anyway, I moved my family up there to Oklahoma. Matter of fact, my youngest daughter is working there now, taking care of my grandson and granddaughter.

Learning the Language of Horses

During one of your visits to your father, he tried to educate you about alternative ways of working with horses. What exactly did he do?

He took me to California, outside of Bishop, a place called Montgomery Pass in the Indio Mountains. At that time there were still lots of wild horses around. Dad loved to go camping. He’d load up a pack horse and ride off and be gone fishing for two or three days. So we put a little camp together. We could look down and see these horses in the valley. I said, “I want to learn horses.” He said, “If you want to learn, just shut up and watch.” So I’d sit there and watch the horses. I’d say, “What am I supposed to do?” And he said, “Watch the horses. If you want to communicate with them, watch how they communicate.” I didn’t get exactly what he was talking about.

Looking back, what did you see?

I saw that horses communicate with body language and how subtle they are and how aware they are of other horses’ body positions – all the little things that led up to that communication. I had a great start; it just took me another thirty years to figure it out. I had to go back and watch a lot of horses, just like my two horses out in the pasture.

Dad would always tell me, “Watch how they prepare. The horse never does anything without getting ready. You need to see how he gets ready. That’s part of your training. If he’s getting ready to kick you, you need to know that. If he’s getting ready to buck you off, you need to know that. If he’s going to do something you want him to do, you need to know that. But you need to know how he gets ready, not wait until after the fact.” He really tried to impress those things on me then, but it took me a lot of years to really understand the importance of it. He gave me a good basic education; I just squandered it.

“Every time you pick yourself off the ground, you start thinking there’s got to be a better way to do this.”

You just weren’t ready.

Well, every time you pick yourself off the ground, you start thinking there’s got to be a better way to do this. Over the period from when I was sixteen until I was thirty-five, I had my back broken in six places and I got my neck broke; those were at rodeos. I had my face totally wiped out when a bull hit me in the face and broke both my jaws and my nose. I broke my pelvis when I pulled a horse over on top of me. I had my knee totally broke. They didn’t do much reconstruction surgery back in the Sixties, so they just put it all back together in a cast and sent me home.

In those days, when you got hurt, unless it was something like my back and my neck being broke, for broken arms or broken legs they’d take you from the rodeo to the emergency room, patch you up, tell you to see your family doctor when you got home, and send you on your merry way because they knew you had no money so they weren’t going to admit you to the hospital. Most of the time, we had no home or family doctor. A lot of times we’d drive down the road, cut the cast off, and go about our business. You couldn’t ride with a cast on, so we’d just take it off. Now, at sixty-four years old, I’m paying for some of those deals I did. My knees bother me. My back bothers me.

Your face turned out okay.

I had another three rounds of that last year. A horse pawed me, busted my jaw loose, and knocked all my teeth out.

So these things happen even now.

Now, that was my fault. I walked up to the horse, thinking about something else. I reached to grab the halter, I scared the horse, and he did that with his front foot and hit me right square in the face. I had three rounds of surgery to get all the bone chips out of my jaw. I ended up with a full round of dentures, upper and lower. I told the doctor, “This is my second go-round at plastic surgery and I still look like this.” He said, “I’m not a magician [laughs]. I had to have something to work with when I start.” I thought about all these women getting plastic surgery and looking so good, and I get it and I look just as bad as I did when I came in.

Were any of those injuries from getting in fights with humans as well as disagreements with horses?

Fights weren’t anything. I think I’ve had my nose broke about seven times. Most of it was just cuts and bruises in fistfights. It wasn't like now, where somebody goes to a parking lot, gets a .12-gauge shotgun, comes back to the bar, and starts shooting. Back in those days, you could have a fistfight out in the parking lot at a dance. Five minutes later, you go in and buy him a beer.

Adrift on the Plains

Even when people were fighting, in the back of their minds they knew it was going to be over in a second. They didn’t take it personally.

They didn’t. I remember one time I was living with three or four guys. We had a travel trailer that was about half as big as that one, parked in a trailer park in Oklahoma. There was one bed, so we’d lay on the floor or wherever we could. We’d gone to town one night. In the course of eating, drinking beer, and shooting pool, we got in an altercation with some of the town boys in there and got in a pretty good fistfight. After it was over, we went back to the travel trailer and passed out, just to be polite about it.

One of the guys got up the next morning and said, “Damn, it rained a lot last night!” I said, “I don’t remember it raining.” He says, “Look at the water out there.” I go to the door and all you can see is water. It’s everywhere. The little travel trailer is doing this. [Powell simulates bobbing back and forth.] You can’t see any other trailers in the park; it’s empty. I thought, “Man, this is another Noah’s Ark deal.” We stuck a broom out the door to see how deep the water was. It was about that deep [i.e., a couple of feet], so we got out and waded around to the corner of this trailer, which was floating. We could see some land, so we waded out to that.

About that time, this old man comes driving up in a pickup and says, “What in the hell are y’all doing in my pond?” We said, “What do you mean?” He said, “That’s my pond. What do y’all got that trailer in there for?” We said, “We don’t even know where we’re at.” He then explained to us that we were about twenty miles outside of this little town. Apparently, after we’d passed out, these boys we’d been in the altercation with had come up, hooked up our little trailer, pulled us out of town, backed us onto this pond, and unhitched us. We had to pay the old man for damages and get somebody to pull our little trailer back to town. Then one of us said, “You know, we need to hunt those guys up and have a come-to-Jesus meeting about this.” I said, “We can’t afford this again. It’s already broke us to get this travel trailer pulled back to town. We’d better let it go.” We laughed about that for a long time. Those are just things that happen. The major things were the broken back, the broken neck ... Yeah, but lying in a bed with a broken back, when you’re looking down and you see the sheets laying on your toes and you can’t feel it, that’s a real awakening.

That was part of the process that led you in a more holistic direction.

It started me in the right direction. It didn’t get me there. When you’re twenty-two or twenty-three years old, you’re immortal. I mean, I’ve thought, “I’m going to walk again.” Then a year or two later I broke my neck and I was back in the same situation again. After a while you get to thinking, “This is not working out like I had it planned.” The other thing was, it was causing a lot of problems with my wife. I had an in-your-face attitude. Some people have a chip on their shoulder, and I have something about the size of this porch. That won’t get you anywhere.

In our next installment, Sam discusses celebrity clients, the wisdom of ancestors and the influence of Zen on his training methods.

###

Great part 1.