Even before singing his first note, the Reverend Solomon Burke had already won over the audience that night at Nashville’s Belcourt Theatre. Darkness still obscured the stage as he was carried into view, seated on a gaudy throne. It wasn’t a gimmick; the fact is that this giant of American music was a physical giant as well, having swollen to just south of four hundred pounds. But from the moment the stage lights snapped on to the end of the concert maybe an hour later, he radiated more energy and charisma than headliners half his age and weight. His patter between songs was irresistible, his demeanor segueing smoothly from comedy to piety to playful ribaldry.

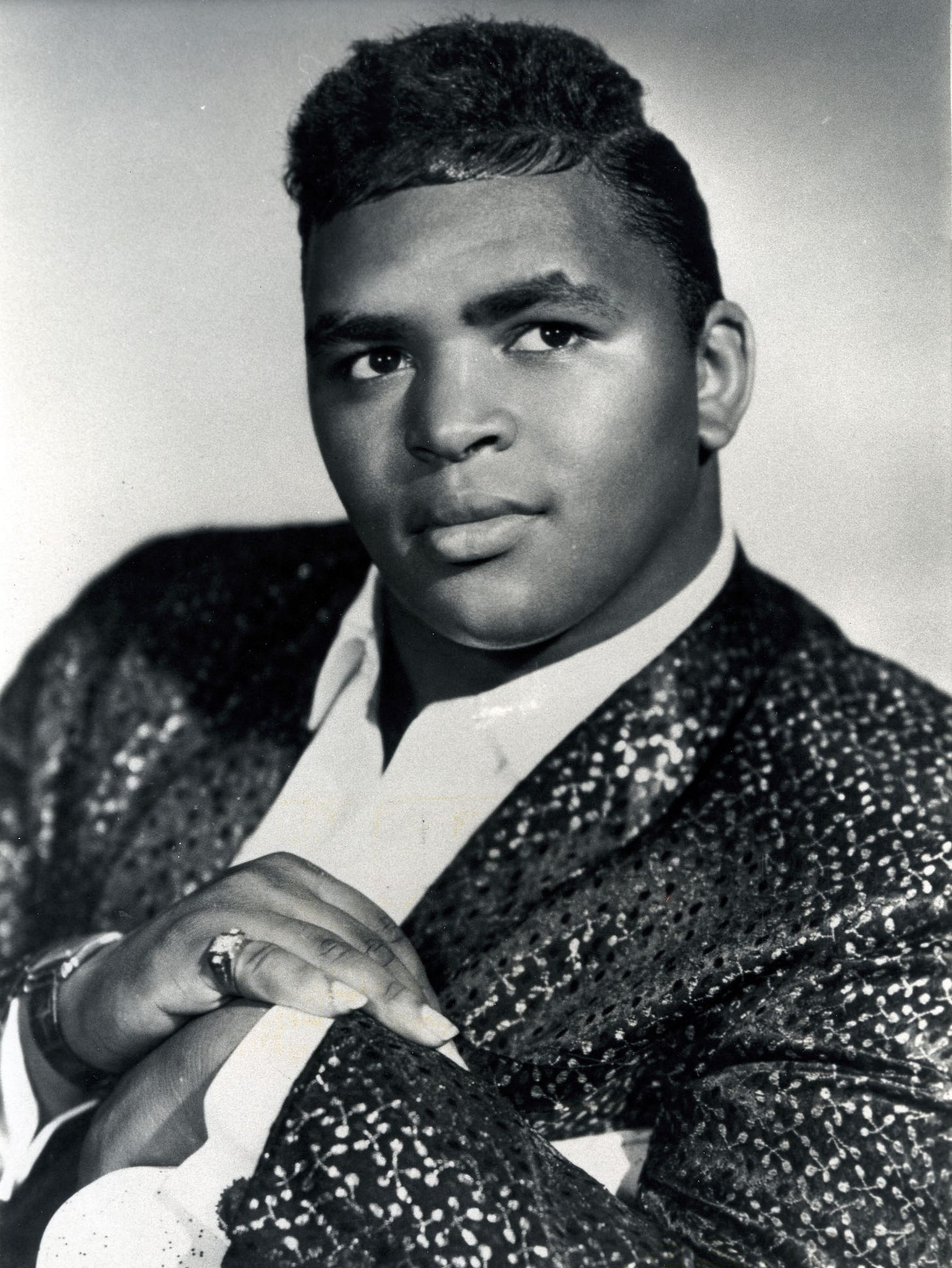

Most important, his voice whispered, soared, thundered and caressed, making it clear to younger attendees why Burke was one of the first and most acclaimed vocalists to blend R&B and gospel into a potent musical combination. Even in the mid 1940s, when he was around seven years old, signs of a fathomless potential surrounded him, not just as a singer but as “the wonder boy preacher” at West Philadelphia’s United House of God for All People. He was still a child when he began hosting his own local radio program, Solomon’s Temple. By age twenty, when Jerry Wexler became his producer, Burke was fully a professional onstage, behind the pulpit and in the studio.

Through the early Sixties he lofted a string of singles toward the top of the R&B charts. Some of them are classics: “Cry to Me” and “Just Out of Reach (of My Two Open Arms”) (1961), “If You Need Me” (1962), “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love” (1963), “Got to Get You Off My Mind” (No. 1 on the R&B charts, 1964). Like Sam Cooke and Ray Charles, Burke drew from the well of gospel music but had no problem singing about both spiritual and physical love, with equal conviction. Wexler called it “soul music.”

That Belcourt appearance marked his latest milestone, a country music project released as Solomon Burke: Live in Nashville. Burke’s love for the sound and feel of that genre had been documented previously, but this night represented a full immersion into the genre. Many of Nashville’s best musicians and artists clustered around his throne: Emmylou Harris, Patty Griffin and Gillian Welch sang as Buddy Miller led the all-star band, whose members included bassist Michael Rhodes, guitarist Kenny Vaughan and multi-instrumentalist Sam Bush.

Burke and I spoke a day or so later. Looking back, I’m struck by the similarities between our conversation and two other interviews I’ve done. One was with Sam Moore of Sam & Dave, whose enthusiasm for both corporeal and spiritual life illuminated his recollections. And the second, with bassist, singer and songwriter Rick Danko from the Band, conveyed a sweetness that I sensed as well in Burke. Sadly, it also forecast the end of his story: Just three days after our chat in Ann Arbor, Danko, who was also alarmingly overweight, passed away while on the road.

The clock was ticking as well for Burke. He hung on for another three years before also dying in the midst of a tour, this one far off in The Netherlands, leaving behind a legacy that warms me even at this moment.

(The transcription begins in mid-sentence, when I began recording.)

****

... Oh, my God, this is like a first for me. Come on, I've been in this business for fifty-two years, but I’ve never had the opportunity to present myself to a music city, to people who really know music and understand what’s going on. I wanted to do the right thing. I wanted to do it the Nashville way. But I just felt like I wasn’t doing it good enough. I felt like, “This is not my normal cake. I make a better cake than this. Okay, I didn’t put enough icing on it or something.”

Yet it’s obviously you singing on Nashville, even as you cross over to a different style and repertoire.

I love it.

You’ve been familiar with country music since childhood.

Absolutely, they just had to put me up there and say, “Sing all the country songs I know.” And I said, “Okay, see if you can follow me, ‘cause here I go [laughs].”

When you were a child, your grandmother played an especially important role in expanding your musical tastes.

She was a big influence. Grandpa was Portuguese and West Indian, so she had this flavor of music in her. Being a very powerful and spiritual woman … You must know the world. Here was somebody telling me when I was a kid that if I was going to see the world I had to know the world. You’ve got to realize and represent. At the same time you have to respect. Don’t say that because you’re black, you’re going to sing blues and gospel and get on down. Learn that there are other cultures. I had a great, famous cousin, you know. People would say, “Shh, this is your cousin. Listen to him.” And we’d listen to his great records. His name was Paul Robeson. I’ll always remember his voice [sings]: “Well, they call him Joe [unintelligible].” Now, if you can do that, it brings the roundness out. He was so incredible. You’d have thought she was a music teacher, but she wasn’t. She was just a woman who said, “Enjoy and respect the fruits of life. Take all you want but eat all your cake.”

How well did you know Robeson?

I never had a chance to meet him. I only met close cousins of his. It was always a thing of, “He’s going to be in town!” “No, he’s not going to be in town! You won’t get a chance to see him.” “Yes, we will get a chance to see him.” And we got a couple of his 78s in the mail. That was a treasure. My grandma used to wrap them up in a towel and put them in the trunk. We’d take them out and play them on the Victrola. That was before you were born.

It wasn’t that long before.

You don’t know anything about a Victrola [laughs]. The Victrola is one of those things you put the record on and you wind it up.

The Seeds of Country

You were singing at a very young age, but even then were you influenced by country music?

Absolutely. There was a minister who traveled with my musicians. His name was Reverend Crumwell. He played what we called the Hawaiian guitar; it’s what they call a steel guitar in country music. It’s forever present in my mind, along with the trombones and the tubas and the big bass drums. That’s the way we had church. That was what you call shoutin’ time. There was a shouting time, a praying time, a preaching time, and a moaning time. Everybody loved the shouting time.

When did you start singing in church?

I started really messing with it when I was seven years old.

And had you listened to Hank Williams and people like that at the time?

I didn’t know of Hank Williams as well as I knew of Gene Autry and Roy Rogers because that was every week. You’ve certainly heard of “Your Cheating Heart” and things like that. Those are important songs, things that had a story. My grandmother would give her messages on stories, on things that would relate to people – not just Daniel in the lion’s den or Jonah in the belly of the whale. She would say, “Preach about your cheating heart this week. We’re going to talk about that. Talk about ‘the things I used to do, I don’t do no mo’.” It was stuff like that. And my mother loved Ray Charles. She lived down the street, and there were times I had to walk down the street to tell my mother that my grandmother said, “Turn down that radio [laughs.]” I couldn’t tell her that; I’d have to bring a note from my grandmother that said, “Turn down that radio.” You’d hear [singing], “I gotta woman way ‘cross town …” People enjoyed themselves that way.

How do you see the differences in musical styles?

There’s a song that says “may the circle be unbroken.” When you place them in the circle of life, country, pop, rock, blues, jazz, soul, it all becomes a revolving ball of music. When you get a chance to listen to it all, it’s special when you can listen to something and say, “I like that! Hmm, that’s okay. It doesn’t fit me.” There’s a girl named India Arie [Simpson]. I love her! She has what you call that catch of soul that puts you right there in her house, right there with her, which is so magical. My daughter Candy plays her all the time: India Arie … country music … India Arie … country music … Patsy Cline. And I said, ‘You know, you’re twenty-eight years old and you’re worse than your dad.”

Where gospel singers often improvise in their performances, country singers usually stay right on the melody …

Right there! That’s what I had to learn. In my childhood, Brother Joe May was so influential to me as a gospel singer, and the Ward Singers, Mahalia Jackson, and Al Hibbler, who didn’t sing gospel but he sang “He could turn the tide and calm the angry sea.” And then you say, “Wow!” And Roy Rogers could soothe you back and say, “Happy trails to you until we meet again.” And I’d say, “I want to hear you again! I hope someday I meet you!” You actually felt the sincerity of him and Dale Evans singing together. There was love. It was real. When I sang Nashville in the hallway with Buddy, the only thing I could think of was Gene Autry singing on the porch, with just the bass and the guitar on one of his songs. [Sings]: “And the roses bloomed and the morning came, and you were there.” Wow! That was the magic that was happening there, in learning to be able to sing in that certain tone and in those certain keys and being able to sing on-line, as I would say.

That forces you to get even deeper into each word.

Yes! You concentrate more! It’s like surgery: The more you go down, the more you find: “Oh! Another note [laughs]!”

“What we did in Nashville was real. That’s what I longed to do for forty-five years.”

How would you compare the Nashville sessions with the classic work you did with Jerry Wexler?

Well, number one, we’re talking about New York musicians who were super-smart, super-slick, and were trying to copy the music that they heard, reproducing the country song with the Ray Charles Singers [sings]: “Just out of reach” and that kind of thing. What we did in Nashville was real. That’s what I longed to do for forty-five years, to be in the heart of it, in the substance of it, to see where the foundation became the rock and feel the impulse behind it. That’s what happened there. That’s why I wanted so bad to have more time before singing for the people in Nashville. But they were like, “Let’s do it! Let’s do it!” And I said, “Well, I don’t think I’m ready.” It was the first time in my career I ever said, “I don’t think I’m ready.” I wanted to be right. It’s not like I was singing at the Grand Ole Opry, where everybody comes to just hear you sing. But that night the president of my record company was there. He was in the audience, looking at me like, “Solomon, you’d better not blow it. This may not be your first record but it could be your last [laughs].”

The Nashville Tracks

Where did you get the idea for this project in the first place?

I was thrilled to have the opportunity to sing at the Ryman at the [Americana] awards. After meeting with Buddy [Miller] and singing with him … Actually, we had a little show together before then. We met the day before at the Mercy Lounge. But the next night at the Ryman, when we did that song with a two-minute rehearsal, I said, “I’ve got to do something with this guy. This is the man. He’s the one who can hear what I’m saying and will help me make it right.” That’s why you see the songs on this album actually tell that story. At the end of the album I sing a song that means so much to me; it says, “I’m gonna keep on doing it until I get it right.” It’s not just about falling in love; I’m going to keep doing this music, if the Lord is willing, until I reach the hearts and minds and souls of the people.

You recorded this at Buddy’s house. Was it important to do this at a relaxed, lived-in place, rather than a regular recording studio?

I don’t know what the plan was, but whatever it was, it worked. It was a shock to me because I was looking forward to going to one of the great Nashville studios that I’d read and heard about. Then I said, “Well, maybe we’re going to his house to be prepped [laughs].” I just followed along with the procedure. We get to the porch, and “let’s start recording!” We recorded from the porch to the living room to the dining room to the hallway, the kitchen area, and out to the back porch. It was magnificent.

What about the bathroom?

I figured we’d save that for the next record [laughs].

You have so many great musicians on this record. How many of them were strangers to you when the sessions began?

Personally, they were strangers, but not musically. That was overwhelming, to sit there on that stage and see this great writer and guitar player, Paul Kennerley, in the audience and not up on that stage with us, I couldn’t take it any longer. I just had to get him up there. He had no intentions of coming up there, but you saw what happened: It was incredible. He just pumped it out. And our violin player, Sam Bush … Sam the man! He plays everything! You look around: “What is he playing now?” And that guy on organ, Phil Madeira? He’s irreplaceable. And my favorite guy back there, the steel guitar player, Al Perkins? Oh, man, that’s one of my favorite instruments. And Buddy’s over there, pickin’. This is an all-star band. These guys are monsters by themselves.

You covered the famous George Jones and Tammy Wynette duet, “We’re Going to Hold On.” Did you listen to that record before recording or did you come up with your own version from scratch?

We heard the record one time. When Buddy said, “There’s going to be a surprise,” Emmylou was originally going to let me sing two of her songs. But when she said, “No, I want to sing that song with him, I want to sing the George Jones song,” I said, “Look, Miss Lou, you can sing the newspaper with me. I don’t care. Just sing something with me.” I was overwhelmed, man. I think I was star-struck: Here I am, with all these superstars. It was blowing me away. And my daughter was sitting up there, saying, “Do you know who that is? Did you know that’s Emmylou Harris?” Oh, my God! So you can imagine what was happening to me. I apologize if I didn’t get it all right this time, but if I get another shot at it, I promise you, I’ll do much better.

It would be great to take that second shot on the Grand Ole Opry.

Oh, my God, I would love that! You are the man! I gotta get you a Nashville hat!

Music in Transition

How do you assess the state of music today, especially when compared to the Sixties, when you had a lot of crossover between black and white markets?

The music has become greater and more credible. The artists are beginning to study the music a little more. They’re listening to their own lyrics. Even the rappers are changing their tune. Their message is clearer and purer. They’re cleaning up their act. It looks like show business on television again. It looks good, not just nasty, you know what I’m saying? You want to see what the next artist is putting out. Christina Aguilera? Come on, she got on a piano, and it took you back – boom! – to real music. Madonna can reinvent herself anytime she wants to. George Jones’s songs last forever. Tom T. Hall can do no wrong. If you listen to Patsy Cline at night, when the lights are out, you put yourself right in the position of crying with her. These are the things that are changing music today.

Have you thought of doing big-band or jazz standards?

You know what, my friend? That’s something I really want to do. You go ahead and get a few together for me because that may be the next album. Wouldn’t that be great?

You must have listened a lot to Joe Williams …

Oh, my God: Jimmy Rushing, Count Basie, Duke Ellington. I’d love to do a whole series like that. We should never forget Joe Williams, Dinah Washington, Brook Benton … and I’m back to Al Hibbler: “Ebb Tide.” So many great things could be happening.

One can only wonder what would have happened had Sam Cooke stayed with us a little longer.

Oh, my God, Sam and Otis and Jackie Wilson. Come on! We were friends. We traveled together. We sang together. We talked together. We laughed together. We had fun together. We were brothers, in the same lodge [laughs].

Otis knew country music well.

Let me tell you, Otis loved country music. And I got Otis stuck on one of my songs, “Down in the Valley.” We had Joe Tex with us for three years because [unintelligible] record. And Joe Tex was total country! I mean, listen to some of Joe Tex’s songs. You say, “My God, this boy was a cowboy!” One time he rode out onstage with a horse! He spent all of his money to rent a horse, just to ride out onto the stage [laughs]!

Was it true that you co-wrote “You Can Run But You Can’t Hide” with Joe Louis?

What happened with that song was that it was a spiritual inspiration for me. Being fourteen, after listening to so many things, I would write songs instantly, and Howard [sounds like: Base] would put it together and Charlie Bernstein would put the music together, and we’d record at Apollo. [Sings]: “He keeps his eyes on you. His love is always true. No matter what you say or do, you can run but you can’t hide.” And then Charlie Bernstein said, “Oh, man, let’s write that!” After writing it and putting it out – I wish I could get one of the original records – we were sued by Mrs. Louis, who was also his attorney. He had copyrighted that byline that Joe Louis said in 1941 with Billy Conn at the end of the fight, when the announcer asked him, “Joe, what did you think about Billy Conn running all around the ring like that?” And he says, “Well, you can run but you can’t hide.” She copyrighted it, so legally we had no right to the title. The record company, instead of going through the lawsuit and losing all credibility … because who’s going to sue Joe Louis? Come on, you’d have to be crazy. So they combined the idea: Joe Louis traveled with me for one year at the expense of the record company. He introduced me at all my concerts, the TV shows, the Steve Allen Show … We had to pay him, put him up in the hotel, supply him with the limousine and food and everything else, for one whole year. And that was the greatest year of my life because I learned how to pass out Joe Louis pictures [laughs]! I was the kid with the pictures! “Hey, kid! Come here!” What Joe Louis said on a TV show was so funny. Steve Allen said to him, “So, Joe, who have you brought with you tonight?” Joe said, “Uh … Dick Haymes, from Decca Records [laughs]!” Dick Haymes had covered the record, so he was thinking about it.

###

He was one of the great ones- his classic '60s sides still sound great and he continued to cut more of it up until his death. Besides which, he was a very enterprising man who seemed to have a seemingly endless number of "side hustles" going on besides music- he got banned from performing at the Apollo because he undercut their concessions by selling his own "magic" popcorn!

Burke was one of the evening headliners at the Edmonton Folk Music Festival in the late 1990s. What an absolute force of nature he was.