Back in the Eighties, when people I knew were lining up for the next Star Wars sequel, or puzzling over Rubik’s cubes, or gushing over what a great role model Cliff Huxtable was, I was reading translations of Vladimir Vysotsky lyrics or Yevtushenko poems. From my modest flat in then-affordable Palo Alto I marveled at photos of old Russian cathedrals, the explosions of color on their onion domes and the neo-Byzantine icons, august and severe.

It’s hard to say why these things fascinated me so much. I didn’t speak Russian, though at one time I attempted to study the language until running headlong into what my teacher called “ Latin cases.” “I must apologize for my language,” she said, with sympathy. But I was already out the door, assuming I could find translators in the USSR after I had disembarked at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport. All I had to do was to persuade my superiors at Keyboard Magazine to pay my adventure.

Strange as it now seems, they did. I assume the main reason was that they had done so a few years earlier, when they picked up the tab for a two-week immersion into the world of keyboard musicians in Japan. I came back with lots of good stuff: interviews with synthesizer superstar Isao Tomita and the iconic Ryuichi Sakamoto, with executives from the Yamaha and Roland corporations, even with the head of the mega-corporation that owned Yamaha, for which I prepared by getting fancy bilingual business cards printed up, learning how to bow when presenting them and allowing for very long pauses between my questions and his answers, as was the Japanese custom.

My Russia trip paid off too, even winning me an ASCAP Deems Taylor Award for excellence in music journalism, which Hal David, who presented it to me in New York, confided was the only submission that the ASCAP panel approved unanimously. The two expeditions were in practically every way different, though there was one similarity: rampant heavy drinking. I saw businessmen in Tokyo subways, their suits buttoned, ties tightened, passed out on the platform near a puddle of their own vomit. The Russians were more discreet, or maybe they just handled it better. But boozing was, for both, the lingua franca, so to speak.

One example: On my first night in Moscow, accompanied by my translator Vladimir Pervukhin, provided to me by Novosti Press, I was welcomed into the home of the virtuoso jazz pianist Leonid Chizhik. He and his wife had laid out a feast, which included ample supplies of vodka. At that time, wine was the only booze I’d ever sampled, so I whispered to Vladimir, “How do I drink this stuff?” “You swallow it fast,” he replied.

Which is what I did, repeatecly, over the next several hours, following toasts to each other, to America, to Russia, to jazz, to world peace, to whatever else we could think of. As we finally said our goodbyes, I lurched over to Chizhik and we embraced each other like brothers. “I’m just glad I’m not driving,” I slurred. And Vladimir added, “Bob, so are we.”

I never got that blotto again, in Russia or I think anywhere. But that vibe was characteristic of every visit, whether with “official Soviet artists” and his colleagues set up interviews, or the so-called “amateur” musicians. The former group enjoyed all kinds of privileges, including access to huge venues and even stadiums for their concerts, as long as their songs were innocuous love ballads or ringing paeans to Soviet patriotism. The amateurs could perform only clandestinely, sometimes in basements or bars. Their recordings circulated through underground channels, on reels or cassettes that were known as samizdat. Each recipient would keep the tape, then make and pass along a copy to the next link on the chain. Presumably distribution ended when tape hiss finally drowned out the music.

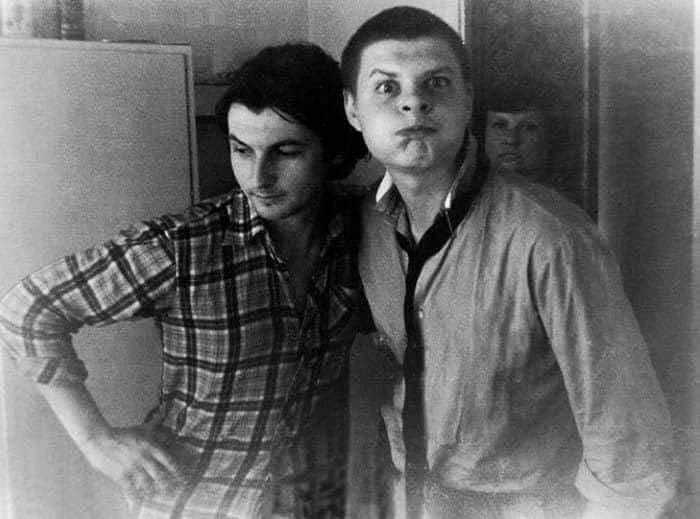

I spoke with musicians from both worlds, using separate teams of f translators. For the latter I relied on two invaluable colleagues, “Big Misha” Kucherenko in Moscow and Alex Kan in what was then Leningrad. I’m happy to say that both have prospered in post-Soviet times, with Alex settled in London and working for BBC’s Russian Service and Misha remaining in Moscow, where he enjoys double-barreled recognition as a pioneer in Russia’s high-end audio business and a connoisseur of fine cigars.

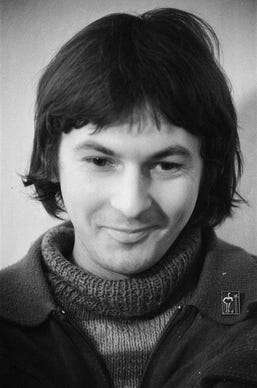

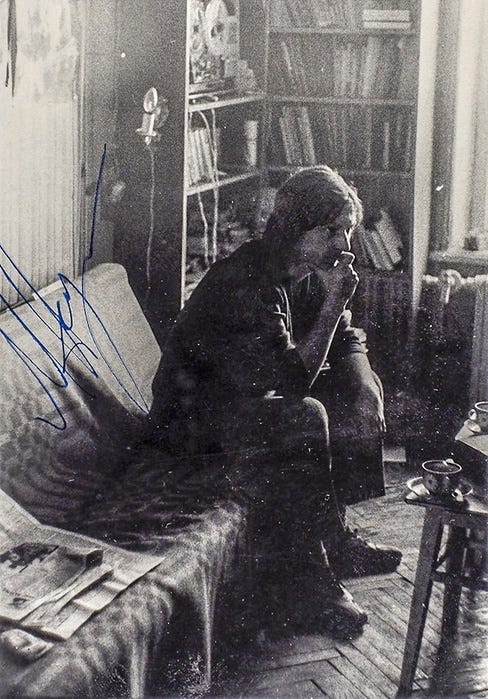

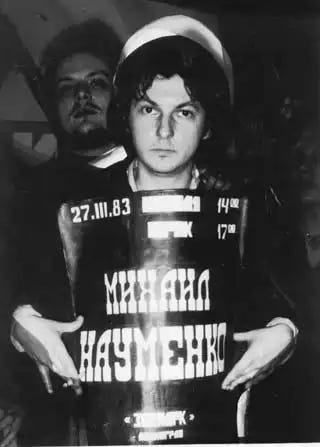

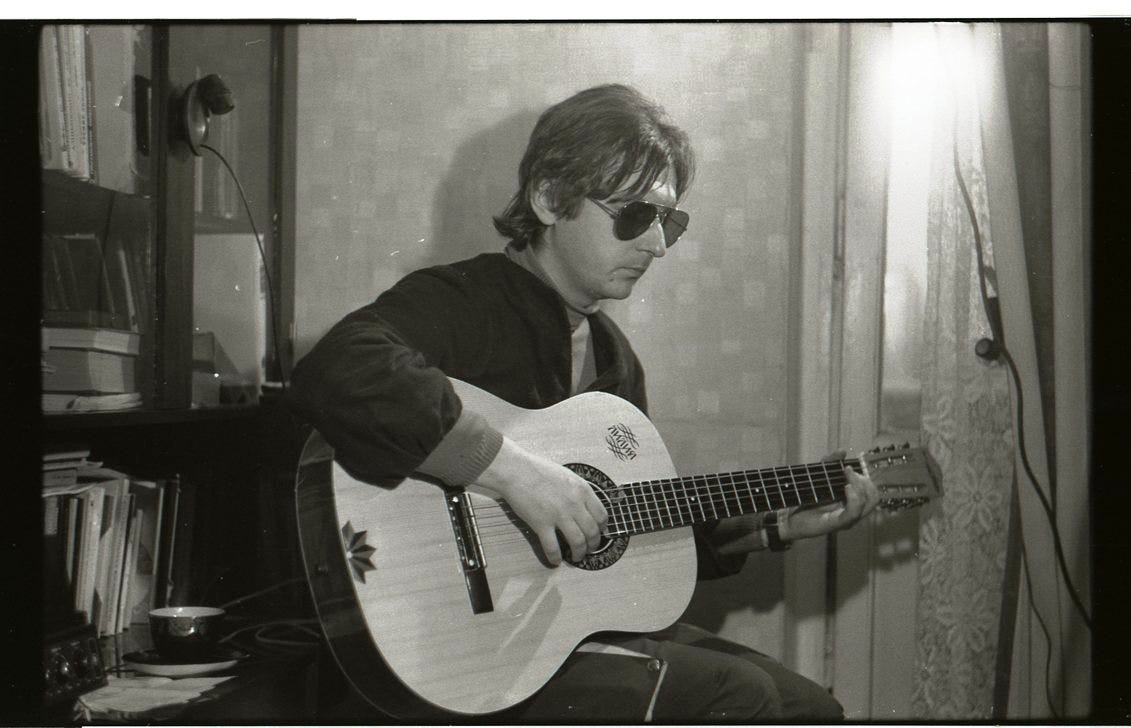

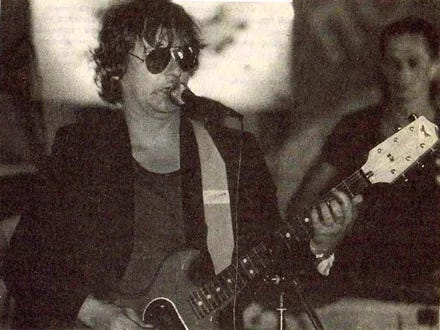

This interview, with songwriter/performer Mikhail “Mike” Naumenko, took place in Leningrad, so Alex did the translating. To be really honest, and with apologies to Alex, I don’t actually remember doing this one. Others remain clear in my memory: that night at Chizhik’s place, at a Leningrad cafe with the astonishing Sergei Kuryokhin (which was posted here previously), at a secret location that involved taking multiple buses and evasive walking to reach an especially notorious underground artist and reputed anti-Semitic polemicist and in the apartment of Boris Grebenshchikov, whose reputation as “the Russian Bob Dylan” had been compromised shortly before our meeting when he signed on the dotted line and became an “official” Soviet artist. (“It means,” he confided as we drained a bottle of Japanese sake, “that I am dead.”)

But for whatever reason, I can’t summon any picture of my sit-down with Naumenko, even though he too was often anointed “the Russian Dylan.” It seems that the chief difference between the two is that Grebenshchkov’s lyrics were noted for their rich symbolism, rooted as much in folklore as in Dylanesque poetic obscurities, while Naumenko was credited with integrating vernacular expressions, the “language of the streets,” into music. Again, not speaking Russian, to make sure I could acquit myself adequtely, I had to rely on research in advance of my trip and on Alex’s insights, which he shared with me before and as we sat down with Naumenko.

One more thing: I’m posting this transcript in part because it’s one of the few among the Russian encounters that I’ve been able to find. (It was stuck in an obscure file, as a dot matrix printout.) Luckily, it also illustrates how I tried to compensate for my disadvantages – speaking only English and being unversed in the complexities of Soviet popular music – by crafting questions based not so much on advance knowledge as on listening for clues on how to proceed toward some interesting elaboration. For example, knowing that Mike was an especially important and innovative lyricist, I figured I'd ask whether audiences sometimes applauded individual lines in his songs; when he affirmed as much, that led me to request a few examples. And my question about whether he felt Americans would be able to really understand what he was saying triggered a response that I found illuminating in a way I had not expected.

So, pour a little Stoli and have a seat somewhere in Leningrad, nearly fifty years ago.

****

You’ve credited a lot of Western musicians as influences, particularly in writing lyrics: The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Lou Reed, David Bowie and so on. But life here is so different from where those other writers lived. Does this mean that your creative process differs from theirs?

Well, I’ve never lived in the West, so I don’t know what I would be writing if I lived in America or England. I’m writing about things that are important to me, aspects of our kind of life. Sometimes they’re dirty, sometimes they’re clean – a supreme love or maybe dirt.

You write about the whole spectrum of life.

I think so. Not all of my lyrics come from me. I write as if I’m a hero of the song. I’m not always the hero of the song. Sometimes the writer writes a novel in which there are ten heroes, each of them with his own opinion. Sometimes, the opinions of the hero in my song are not my opinions. It’s about situations. So I’ve been accused of being a punk, being a racist and so on. I was never a fascist! I’m against it. I’m no punk. I’m a bit older than the punks are.

Of course, but maybe your lyrics were so persuasive and sincere …

Maybe, maybe. I don’t know. It’s not my work to judge my own lyrics.

Can you pick out some lyrics that have been especially misunderstood?

Sure. There was a controversial article in a Leningrad newspaper, saying that in Moscow there was a song called “If You Wanted.” They took some lines from the song and put them together as if it were me [talking]. There were lines such as, “We all need someone we can beat, torture or kill. And if you want it, you can kill me.” In the song, this was sung to a girl. They didn’t print the second sentence and instead said that we were inviting people to do the killing.

They deliberately omitted ‘if you want it, you can kill me”?

Yes, of course. We weren’t allowed to play this song in those times. We play it in stadiums now and no one says anything.

But that didn’t persuade you to change your approach to writing songs, to avoid these sorts of misunderstandings. You weren’t intimidated.

I think not. I never write songs that I don’t believe in. There are some songs that are better or worse – but I can write my name under every line, or else I would not be issuing it.

Is it harder to find things to write about, now that the political climate here is less oppressive than it was under Brezhnev?

It’s harder these days because we’re always on tour. We’re constantly working. At last we’re working as musicians. We were all night watchmen and now we’re musicians.

When did this change?

Really, in the past year. We became professional musicians.

Five years ago, did you think that you would ever accept professional status as a Soviet artist?

We always hoped that this time would come. But it was a platonic hope, I would say [laughs]. Last year, when we were playing in a stadium here in Leningrad, we played songs that we had been forbidden to play for four to five years. I asked my bass player, “What would you have said to me five years ago, if I had said we would be playing this stuff in a stadium?” He said, “I would spit in your face.” It’s amazing.

Did these changes seem to come overnight or was there a gradual process of glasnost?

It was getting better day by day. I’m not sure how to explain the whole situation. Suddenly, they allowed us to play some songs that had been prohibited before.

How did you hear about that? For example, did a censor grant you clearance to do a particular song at one gig?

We had some tape recordings which were rather popular throughout our country. There were songs on them which we weren’t allowed to play live. But somehow, we realized that the situation was getting better, so we took them and they were okay.

You took them where?

The Rock Club [a,k,a., Leningradsky Rok-Klub, the city’s first legal venue for rock ‘n’ roll bands, in which KGB and Komsomol observers mingled semi-clandestinely in the audience]. At first, when we played there and in other towns too, the audience would shout, “Play this! Play that!” And we had to say “Sorry!” But there are some people there who approve songs. When they said, “Okay, play it!”, we were like, “Fantastic!”

Is any topic still off-limits for writers these days?

Practically nothing. I never write political songs. I’m more into personal problems than social problems.”

Inspirations

What inspired you to become a songwriter?

The Beatles. Not only me, but I think a lot of musicians from my generation. We were teenagers when we heard the Beatles. We were students. Somehow we got the tapes and records. We were all Beatles fans. We thought that if great guys could write songs like these themselves, why couldn’t we? So we tried to do that.

From the beginning, did you write about both the brilliant and the darker parts of life?

No, I think I grew into that. When I was a teenager, my first songs were teenager songs about love. But life goes on. You become older. There are different problems, different views. I came to accept the views of other people, and it became more interesting for me. So I tried to express not only my views about everything, but also other people’s views about everything. There were people who inspired me for these things: Russian musicians, English and American musicians.

But your primary goal was always to from a personal rather than a political point of view.

Yeah. You know, I am interested in politics. I read political papers. I always watch the news on TV. It’s very interesting to me. But it has nothing to do with our music. I don’t know why.

[Soviet rock critic] Artemy Troitsky says that you surprised a lot of people by writing in “the language of the streets.”

It’s a hard thing to explain, because you don’t speak Russian. There is one language, in which all the commercial stuff is written. It’s roses, kisses, stars above. I try to write songs in the language that is used when people talk to each other.

Did authors also inspire you, such as Aksyonov?

Yes, I know [Vasily] Aksyonov [known for opening the door for Soviet artists to write in a less formal, more vernacular style, about everyday issues, prior to being expelled from the USSR in 1980]. I was more inspired by Jack Kerouac. He is one of my favorite writers.

“I’m against intellectual music. I’m for anti-intellectual music.”

J. D. Salinger?

Yes, but if you want to compare my songs with the words of some writer, maybe Jack Kerouac is the one. Salinger is intellectual, and I’m against intellectual music. I’m for anti-intellectual music. I’m for rock & roll. But it doesn’t need to be too primitive. When we play, there are various kinds of people in the audience. I would like people to be able to dance if they want to, but there are always some people who don’t like 0dancing. When they don’t like to dance, they sit and listen to what I’m singing. So what I’m singing doesn’t have to be too silly.

When you first made an impact on the public here, were the fans as well as Soviet officials divided on whether your lyrics were too vernacular?

I can’t say a lot about the audience and whether or not they dig my music.

(Translator Alex Kan cuts in.)

As a fan, as somebody who has been to a lot of concerts, I can say that the action was immense. He was a very fresh, very strong voice. I first got interested in Soviet rock through Aquarium. But when I listened to the Zoo, it was very different from what Aquarium did, and very strong. Mike was always more straightforward, more open, than Boris [Grebenshchikov, leader of Aquarium]. Boris was more obscure, more mythological. It was also very interesting. But nobody was as straightforward as Mike was. Or is.

What about finding the right music for your lyrics? Does your music also have a rough edge, to mirror your message?

Well, we play just plain rock & roll, although I’ve got some acoustic ballads. I’ve got two loves in music. One is for plain rock & roll. One of my favorites is Chuck Berry. Also the Rolling Stones. The other love is for ballads: Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan. Somehow the mix. Neither one plays very complicated music. So our music, too, is rather simple.

Do your audiences sometimes applaud individual lines in your lyrics?

Sometimes, yeah. Sometimes they sing along with us.

Can you give me some examples of those lines?

Just to put two examples, the first is called “Dryang.” Artoyim Troitsky called it “Bitch.” I’m not sure that this is the best translation.

It’s a pejorative aimed at women.

(Translator Alex again interjects.)

Not necessarily for women. It’s wider. It doesn’t even have to be a person. It could be anything, somewhere between “shit” and “bitch.” It’s a swear word.

(Naumenko continues.)

It’s very hard to translate, right? The public usually sings along with it; it’s one of our greatest hits. The second is called [sounds like “Pravanorokh”] – “We’ve Got the Right to Rock.” It’s a song about rock that had been forbidden early, and now we’ve got our right to rock. The public likes that one. There was a song called “Song of a Simple Man,” with the line “I came to the Leningrad Rok Klub They sing their song in my native language. I like Aquarium.” [Naumenko makes a cheering noise.] “I like Zoopark” [another cheer]. I like Kino [another cheer].” And so on.

(Translator Alex interjects.)

The other line is, “I only like amateur bands.”

Does the public still feel that there’s a split between amateur and professional artists?

Yes. You know, we became professional in status. But we are not professionals in the accepted …

(Alex clarifies.)

They’re still different.

“All underground bands that became professional, not just us, are more honest. And the public knows it. We would not betray them.”

So the definition of professional seems to have changed. You no longer have to be a stupid commercial group. Now you can be professional and still have substance.

We still sing all those songs that were forbidden when we were not professionals. I think that all underground bands that became professional, not just us, are more honest. And the public knows it. We would not betray them.

Did you ever consider just being a poet or writer, or was music always essential to what you do?

Well, I’ve written some poems and short stories. I’ve done some translations. I translated the great novel about [sounds like: Ruzha Bach], called Illusions. This novel shocked me very much. I read it, re-read it, then translated it. I taped it and gave it to my friends. This is a rather popular novel in the Soviet Union, but it is not published. It goes by samizdat.

Rock the World

Is the idea of “Soviet rock” still relevant?

Well, something is always happening in music, especially rock music. Now it’s a strange time for music. Judging by the past two years, I’m not very optimistic about what is happening in rock all over the world.

That’s interesting, because conditions vary greatly from place to place throughout the world.

All of us musicians, I and everyone else, try to listen to what is happening. Some old and, I would say, conservative guys … I mean, I love Mick Jagger’s last record. It was very good. The Rolling Stones and the Kinks’ last record, in 1986. But the best record by new bands in the past year was by a group in Czechoslovakia, recorded in England and produced by John Cale. The band is called Element of Crime. It moved me. It is very simple, rather primitive rock, but with rather good lyrics.

But when you say you are pessimistic about rock, you’re saying that groups like this still do challenging music.

Yeah. I like the old rock more than the new groups. I don’t like computers. Technology is anti-human. Maybe the good drummer will make a little mistake; that will give the music its drive. I’m for people playing music.

You feel that it’s a bad omen when people surrender too much of the process of making music to computers.

It’s a sign of the times. It’s a sign of scientific progress. It’s the first real effort of the public to deal with computers. It’s the first disease. Maybe people fall in love with computers simply because they’re available, like a toy to play with. Maybe the situation will somehow change, maybe it won’t.

And this trend exists here as well as in the West?

Absolutely, even more so than in the West. Because the West has already gone through this stage; it’s developing a healthier approach. Here, it’s still more of a novelty.

I just want to clarify: You’re concerned with the state of rock music throughout the world, but you also feel that in the Soviet Union something different and unique is happening.

I think so. The first thing, which you already know, is that the words are much more important. It’s a very strong, old Russian tradition. As far as I know, poets are more popular in Russia than in the West. People want the new word, something that can move them. That’s the first thing, The second is that when we play music, we use small means. We don’t have good instruments; they are very expensive. We just bought two American guitars, just to get a good sound, and they are so expensive! It’s fantastic. Everyone knows it. So even though everyone wants to get a good sound, the sound doesn’t mean so much. It’s more a matter of drive. We don’t pay so much attention to smoke and lasers onstage. We can’t afford it. So it’s just music; it’s just what we can say.

Do you think you could ever play comfortably and successfully in the West?

We’ve been invited to play in Poland and Finland. I know three words in Finnish and about five words in Polish, and they’re obscenities [laughs]. But they asked us to play some of our songs in English if we perform in Finland. I think we can do that. I use my English in England or America, though, I don’t think anyone would understand me.

“I’m not singing about social problems. I’m singing about personal problems.”

Even if they understand your words, will they understand the meaning of the words as audiences here do?

Well, I’ve told you that I’m not singing about social problems. I’m singing about personal problems, which are more or less universal. Maybe there are some aspects that are more characteristic of our country. Yes, of course. But not all. Songs about love are universal.

So your songs would translate more effectively than those of Grebenshchikov, for example.

It’s an illusion that Grebenshchikov sings very strange and complicated texts. I think his words are all very realistic.

He has to write three new songs in English for his upcoming CBS album. His English is really good, but can he really tailor his words to how Americans think?

Well, there were some great Western groups that sang much stranger lyrics than Grebenshchikov’s, such as Yes or Genesis with Peter Gabriel.

(Alex comments.)

Last night I was with an American film producer and we were talking with Boris Grebenshchiklov. They told me that Paul Simon was once asked what he felt was the best rock & roll line of all time was. Without a second’s thought, he said, “The best line was ‘be-bop-a-loola, she’s my baby.”

Mike, do you agree?

Nik Cohn, the English journalist, wrote a book in the late Sixties, called Rock from the Beginning. The subtitle was: Wop-Bop-a-Loo-Bop, A-Wop-Bam-Boom. What else can I say?. Rock & roll is great. It’s loved by Soviet boys and girls, and by American boys and girls too. I’m glad that it’s still alive. I hope it will live for years and years. It’s our life.

####