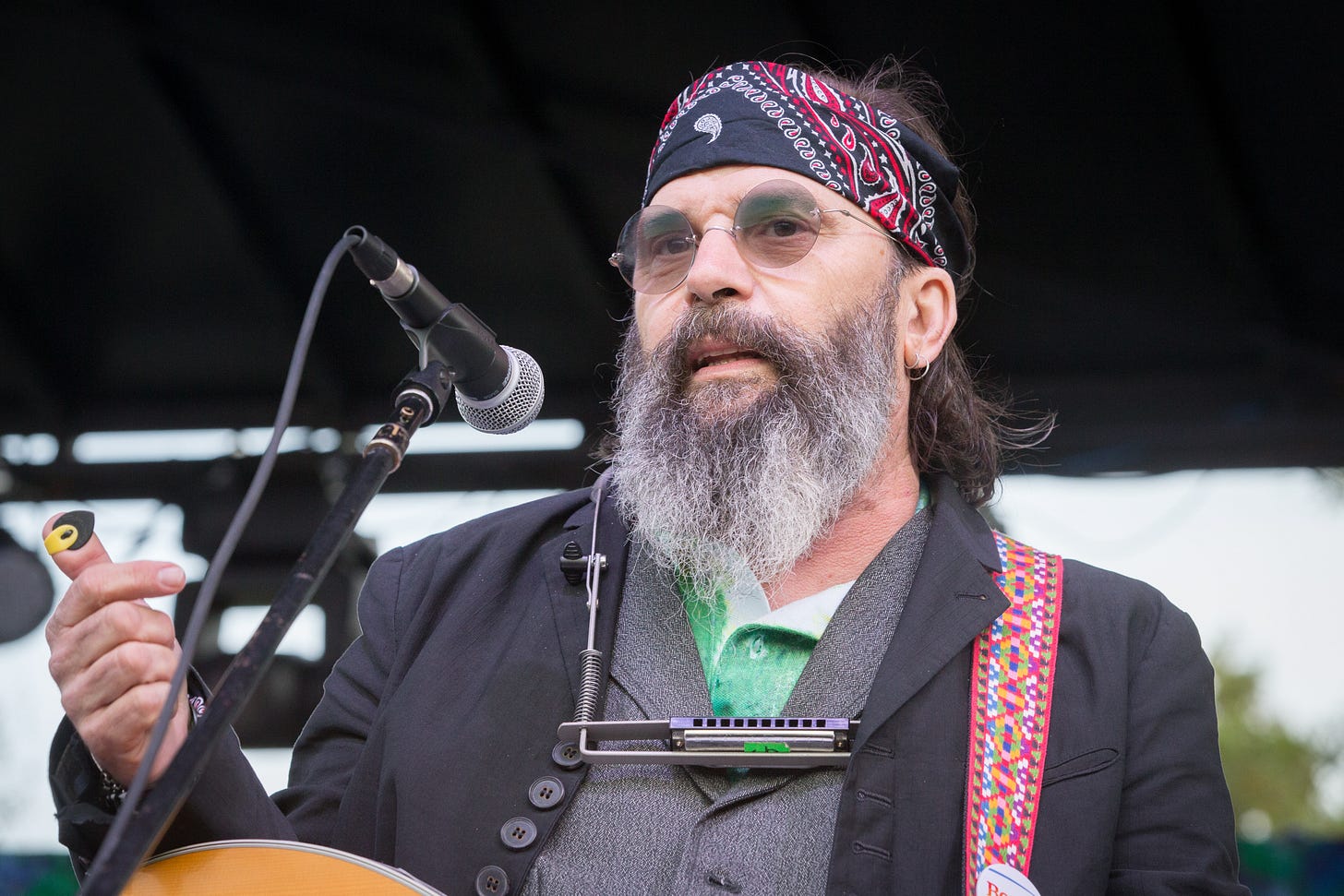

I met Steve Earle right after I’d moved to Nashville as part of the ill-fated Musician Magazine relocation. We were standing next to each other alongside a pool table at a now defunct venue, both of us looking a little forlorn. Someone pulled my sleeve and whispered, “Bob, that’s Steve Earle! He’s one of the most provocative songwriters in Nashville. You should get to know him.”

So I mumbled something like, “Hey, Steve. I’m that guy from Musician Magazine.” We acknowledged each other, probably shook hands desultorily and then stared wordlessly at the game. One of us brought up baseball, for some reason; the other one perked up and chimed in about his fondness for America’s national pastime. Steve let it be known that he was wrapping up his latest album, Sidetracks, a sentimental celebration of our favorite game. A minute later we had confirmed an interview, which I wrote up and sold to the Nashville Scene’s April 4, 2002 edition.

Maybe a year later I was assigned a feature story on Steve, either by American Songwriter or Performing Songwriter magazine. (I couldn’t find the hard copy on my shelves or online, so if you can help me remember which publication ran it and in what issue, I’d be grateful.) When we spoke, Jerusalem had just been released and suddenly Earle became an object of nationalist derision. Gone was the respect he had earned through his early albums Copperhead Road and Guitar Town, obliterated by the controversy of songs like “The Ballad of John Walker”, “Amerika V. 6.0 / The Best We Can Do” and a hymn to the struggles faced by undocumented immigrants, “What’s a Simple Man to Do.” Formerly admiring peers excoriated Earle for daring to find a different perspective in the wake of September 11 than, say, Toby Keith’s call to stick a “boot up his [Osama Bin Laden] ass / It’s the American way.” I even remember hearing conservative radio host Phil Valentine going a step further to declare that Earle wasn’t much of a singer either.

When this story went to print, Earle was already receiving death threats, not just for his paean to John Walker Lindh, an American kid who fled his homeland to join the Taliban, but also for condemning the death penalty, the deepening wealth gap and sharing dark truths about his former raging drug addiction. Clearly it would have been a mistake to avoid addressing these topics, but by letting the conversation wander from there into broader issues of composing, I figured we could have a more fruitful exploration of ideas.

****

We talked about your previous album for the Nashville Scene. I asked whether we needed politically oriented music as much as we did in the Sixties. Your answer to me was, “Yes, maybe more.” Has your perspective on that changed?

Well, there’s always been a political component to what I do. But I still write more songs about girls than I do anything else [laughs]. I wasn’t even gonna make a record this year, but we had what we had happen and I reacted to it the way that I did. I found myself writing a record I’ll probably never make, which is basically an overtly political record. Transcendental is largely a record of chick songs. This is largely a record of stuff that’s more issue-driven.

Every artist I’ve interviewed over the past year or so has at least one song written about 911. There seems to be a unanimity in their responses, from Springsteen all the way down, namely to rally ‘round the flag …

I think that’s an odd way to interpret Bruce’s record. Bruce’s record is doing what Bruce does really well, which is to improvise with a large group of people. It’s a human reaction, a human record. It’s about how people reacted as human beings. I’m a lot more of a political beast than Bruce is. I’m not a political artist but I think more in political terms.

“I’m actually more afraid of our reaction to 911 than I am to 911 happening again.”

So let’s set Bruce’s project aside. Darryl Worley, Radney Foster, Tuck & Patti — so many people are writing songs that are either wounded or patriotic along Toby Keith lines. Your reaction was rather different.

I’m reacting from fear and from pain too. But I’m actually more afraid of our reaction to 911 than I am to 911 happening again. I’m statistically more likely to have my civil liberties damaged as a result of our reaction to 911 than I am to actually being attacked by a terrorist. I’m more afraid of the thing that I think is more likely to happen and that I see happening already.

You got a strong reaction to “John Walker’s Blues.” As you were writing this song, did you know that it would lead to this?

The people that reacted are the people I thought would react. And that’s okay. That’s democracy. The end result is that we’re still talking about John Walker Lindh two months after people were trying to get him off the radar.

You’re not advocating anyone’s position or point of view …

No, but I’m trying to put myself in John Walker Lindh’s shoes. I’m assuming that I know something about what he believed. It’s a presumption, but it doesn’t necessarily reflect my own voice.

Everything you write in this song is a reasonable presumption, from the nature of his background to what might have attracted him in the first place.

Yeah, but this atmosphere has caused people to not be able to get past the fact that anybody ever wrote a song about John Walker Lindh. I’ve done it before. I never fought in Vietnam. I’ve never even been there. I don’t grow marijuana for a living, but I wrote “Copperhead Road.” It’s just a ‘me’ character. It’s an important part of the way I write. I wrote a lot in the first person, even when I’m not writing songs. About half of my collection of short fiction is written in the first person. It’s an effective way to write, I think.

You know, back when Guitar Town came out, that record got embarrassingly consistent great reviews. The one negative review I remember was in the Boston Phoenix, from Jimmy Guterman. He was a kid at the time. It was basically a review of what he perceived to be my politics. It was based mainly on “Good Ol’ Boy (Gettin’ Tough).” I don’t think like that guy does either: “Got a $20,000 pickup truck. Belongs to me and the bank and some funny-talking man from Iran.” I was assuming a character — and that character didn’t piss off anybody in country radio [laughs].

I have an agenda when I write a song like “John Walker’s Blues.” But it isn’t necessarily the person telling the story of the song’s agenda per se.

True, but when you listen to something like “Amerika Version 6.0 …”

Well, that is me [laughs]. I’m not a political artist but I am a very political person. I believe there’s no reason for people to go hungry or without healthcare in the richest country in the world. There’s no way you can justify that to me, even though people have been trying to do it for years. I just see more evidence to the contrary every day and I’m never gonna believe that there isn’t enough to take care of everybody in a country as prosperous as we are.

The character in that song is strongly opinionated. But in comparison with “John Walker’s Blues,” you use certain characters — the country-club guy, the HMO doctor — to put your view forth. But the character of a kid in John Walker’s position seemed to be the thing that fascinated you, regardless of what the nature of that position was.

I have a twenty-year-old kid. He’s four-and-a-half months younger than John Walker Lindh. My belief is that this could have happened to my kid. It could happen to your kid. This is a kid who was already looking outside of his own culture. He came to Islam by way of hip-hop, in a very strange way. He was very much immersed in hip-hop culture when he was thirteen, fourteen, fifteen years old. During that period of time he saw Malcolm X, that Spike Lee film. By the end of that story, Malcolm has come to Sunni Islam, which was much easier for this kid to relate to than the Nation of Islam stuff, which excluded him simply because he was white. The big revelation for Malcolm, which caused him to go into a more mainstream part of Islam, was that he’d been lied to, that there was this direct relationship between Islam and his race. He realized that the path he’d gone down was racist, which was not necessarily a part of Islam.

Being that Lindh was sixteen years old when he graduated from high school early, his parents let him go to Yemen to study the Koran and to study Arabic. He comes home and his parents are split up. His father has come out. Any fundamentalist religion, whether it’s Christianity or Islam, tends to be kind of hard on homosexuality. So his world turned upside down — and he goes back. And I don’t think he had any intention of ever coming back when he left the country.

My connection to this was through my son. It bothered me because this is scapegoating. And scapegoating is dangerous. No one else was going to humanize this kid. There were enough people vilifying him. So …

A lot of the rhetoric that we hear these days is intent on demonizing rather than really looking at …

Absolutely. We don’t function well in our society without a boogeyman. And we’ve been rudderless ever since the collapse of the Soviet empire. We’ve had a hard time making foreign policy ever since the Soviet Union fell apart. It was based on our opposition to Communism for so long that I don’t think we knew completely how to act.

It’s easier to deal with boogeymen rather than with someone who reached a position contrary to yours through thinking and analysis.

What we’re doing right now scares me. Scapegoating scares me. Racism scares me.

There are two things I know for a fact that didn’t have anything to do with September 11. One is John Walker Lindh. We did this knowing full well that he couldn’t have any prior knowledge of the attack. The news media and the government very actively tried to attach him to the death of a CIA agent called Mike Spann. He was the guy who was interrogating Walker in those films that you saw over and over again on CNN. He turned up dead later that afternoon. Now, I’m reasonably sure they’d already found out that Lindh was an American that singled him out. I’m reasonably sure he was already duct-taped to the board when Mike Spann died. No one has ever presented any evidence that he had anything to do with Mike Spann’s death, directly or indirectly. And that’s irresponsible. This kid was tried and found guilty by CNN before they even brought him back to this country. I’m not comfortable with that process.

I’m also not comfortable that when I get on an airplane, the computer will pick me and three other people randomly to have our bags searched. But every single person who appears to be a Muslim will be profiled and searched. You can’t convince me that makes us safer. But I don’t think they’re doing it to make us safer. I think they’re doing it to make white Christian people feel safer because we see those people being singled out. It doesn’t take into consideration how those people happen to feel.

Keep in mind: Everyone who looks like that has been searched the extra time every time they’ve gotten on an airplane. I was flying a lot after the 11th and that’s what I saw in airports all over the country.

The New Sixties

You go back to the Sixties, so you remember the role that music played in that culture and climate. Can you compare how the challenges for singers and songwriters today are similar and different?

I think things are getting ready to change again. Things now are a lot like how things were in the late Fifties. You know, nobody had ever even considered pop music to be art. The odd thing that happened was that people like Bob Dylan came along. Dylan came out of the folk music thing but he really wanted to be a rock star and he carried that sensibility essentially into pop music by making electric records and getting played on the radio.

That happened to be going on during the Vietnam war. We came to a point where opposition was growing to the war. And then everything changed overnight for the music business in 1969, when record executives saw 400,000 in one place to hear this kind of music. A lot of it was very topical. Whatever they thought about the war, they recognized that this was a market. And suddenly, once and for all, major labels were in the rock ’n’ roll business. They didn’t really know how to make those records; Mitch Miller didn’t know how to make a Jefferson Airplane record. So for a few years there they just gave money to people they thought could do it, and in the late Sixties and early Seventies there were some amazing records being made.

Right now we’re going through a period where issues are sort of being driven out of pop music. You know, some of the very people who were out in the streets in the Sixties now have become very complacent because they’re heavily invested in stocks and bonds. They’re players in that world. They don’t want to think about those things anymore.

But believe me: We’re on the verge of a war with Iraq that doesn’t have anything to do with September 11th. The administration intended to get us into it before September 11th. In my view, they’re dishonoring the people that died and their families to use it as an excuse to go into Iraq. If that happens, you’re gonna see some bad things in this country, especially in our economy. That’ll be the first thing that we feel, because we can’t afford this war. The last time we fought Iraq, we had other people sharing part of the bill. They’re not gonna go with us this time. And that war, the last one, sent us into a deep recession.

When the Vietnam war ended, there was a vanguard of people that were like me, that were pretty radical and opposed the war from the beginning. But the war ended when people like my father began to oppose it. When 55,000 kids had died, average everyday people started to agree with that vanguard and the war ended.

“My FBI record dates back to when I was fourteen years old.”

So maybe today’s establishment, knowing about that precedent, is particularly vicious in its attempts to clamp down on what they see as dissent. In the Sixties, though, there was a lot of cultural encouragement to dissent. I’m not so sure there is now.

There’s not, but back then we also had J. Edgar Hoover keeping dossiers on anyone who opposed the Vietnam war. My FBI record dates back to when I was fourteen years old. It wasn’t because of drugs. I wasn’t famous or anything. I just showed up at demonstrations.

You must have signed a petition.

No, I showed up and played “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ To Die Rag” at a rally in front of the Alamo. I got my stuff under the Freedom Of Information Act. There’s a picture of me on top of my flatbed trailer at a Vietnam Veterans Against The War rally in 1971.

What would you say to young songwriters about the pluses and minuses of writing from their conscience?

I don’t think there’s ever a minus. You could put a gun to my head and you couldn’t get me to discourage people from writing from their conscience. You’ll reach people faster, because when you’re not writing about issues you’re writing from your heart. And when you are writing about issues, you’re still writing from your heart, not just from your brain. To do this and do it well around issues, it requires empathy more than anything else. I wrote “John Walker’s Blues” out of empathy, not for John Walker in particular, although there’s some of that, but for anyone who is singled out as a target because we’re afraid.

It’s important to write what you feel strongly about because you’ll reach audiences. Audiences can tell. There’s still an audience out there for real songs. Right now the music business isn’t catering to it. Songwriters, for a while, are going to find alternative ways of getting their music to people. There’s less of a chance that BMG or Universal or one of those big labels is going to sign an artist like that.

Of course that game is changing anyway.

It is. There are lots of things you can do. You actually can go get a day job, work for three to six months and buy a rig that you can use to make a record, if you take the time to learn how to do it. That changes the whole landscape.

Is there any argument to be made for striving anyway for a major label deal by doing non-controversial stuff, building a platform and then tackling weightier stuff after that?

Maybe, but I don’t have any personal experience with that [laughs]. I didn’t write Guitar Town [for that reason]; it was just the record that was in me at the time. I’m not a political songwriter; I just don’t exclude issues from my songs. I don’t think Woody Guthrie was a political songwriter; I think he was a songwriter who lived in a politically charged time. I mean, he was an entertainer. He had a very popular radio show in California on a commercial radio station.

“I make an embarrassing amount of money for a borderline Marxist.”

That’s what I was driving at. When you used the word “empathy,” some people might see that as a particularly insidious form of musical dissent. It’s one thing to get up there and say, “Get out of Iraq” or whatever. That’s kind of one-dimensional, so those who disagree can deal with it. But when you write from the heart, you make the subjects of the song human. As far as labels are concerned, that could make them riskier to sign.

Well, I don’t think so in the long run. But if what you’re after is to do anything to become famous and get on the radio, hey, go to Nashville! They’re looking to sign artists who don’t talk back. it’s true of pop music too; go to L.A. if you’re willing to do anything.

But I’m not the same thing as even Oasis is. Oasis exists to get on the radio and sell records. I don’t. I sell a couple of hundred thousand records to pretty much the same people who buy my stuff every time. But I make an embarrassing amount of money for a borderline Marxist. Now, the major labels can’t make a profit selling two hundred thousand records right now. They don’t know how to do it. But they did a really short time ago.

Artemis is an independent label with unusually good funding. This is one label I know that's trying to fill that gap. The very first people that Danny [Goldberg] signed were me, Warren Zevon and Rickie Lee Jones. I might be able to get a major-label deal if Artemis folded tomorrow, although I can’t guarantee that in this climate. But I will be heard.

If you want to put out original material, you don’t have to move to New York or L.A. But you can’t stay in San Antonio, where I grew up, because it’s not an environment that’s friendly to original music. It’s tough to make a living anywhere, but you’re not even gonna get onstage and be heard in the first place in San Antonio. It’s still gonna be tough to make a living if you move ninety miles north to Austin, but there is some tradition of musicians playing original material there. You do have to move to Austin or the Bay Area or someplace where there is a stage and a mike where people play songs that they wrote rather than cover bands and deejays.

Let’s say you’re debuting a topical song in front of an audience. Maybe it’s an open mic night. Should you set up the song by …

It depends. I’m opposed to the death penalty. Pretty much everybody who knows anything about me knows that. But you don’t come to my shows and get beat over the head with rhetoric about opposing the death penalty through the whole show. I usually do one of the four songs I’ve written about the death penalty at every show, so you will hear about my opposition to the death penalty because it’s important to me when I play that song. That’s my opportunity to say it. Then I play the rest of the show. I’ll play “Copperhead Road” and the stuff that people want to hear. So my audience and I have kind of a secret handshake.

This record [Jerusalem] is gonna be different because so much of the material on it is topical. My tendency will probably be … now, keep in mind that the tour doesn’t start until November 15 in Knoxville and I haven’ t started rehearsals yet. But if I was going out to play it tonight, I would probably let the songs do the talking. Sometimes you have to gauge an audience about that.

If you really need to set a song up, you probably need to rewrite it. But there’s a case for setting it up anyway. If you feel the need to tell the audience what a song is about before you play it, you might need to go back to the drawing board. But sometimes … You know, Townes Van Zandt used to get sick of being asked about “Pancho and Lefty.” I heard him one night getting ready to play “Pancho.” Some people wanted to know if it was about Lefty Frizzell and Pancho Villa, so he said, “This song is about Billy Graham and Guru Maharaj Ji.”

Nothing in my show is scripted. It’s stuff that happens spontaneously. But if I say something and people think it’s funny or it seems to help pace the show, I hang onto it and it becomes a monologue by the end of the tour.” There are monologues that I’ve been doing for years. As long as they keep working, I’ll keep doing them.

But you have to get to know your audience. And the only way you do that is to get out in front of them and see if they appreciate it or not. That’s where it starts.

Postscript: “It’s Your Fault! Goodbye!”

Maybe a decade after our last interview, I got a call from Earle’s publicist, who invited me to write a PR bio for his client’s latest release. Based on my appreciation for his talent and courage … and our shared love for baseball … I accepted, happily. A date was arranged for our phone interview. Steve and I exchanged a few pleasantries, then we got down to business. After a few seconds, as I always did, I stopped the tape to confirm that we were recording successfully. Unfortunately, his voice was muffled. So I adjusted volume levels and asked Steve to do a “testing, one, two, three.” The problem persisted, so since my voice rang out clearly on playback, I suggested that maybe something was wrong on his end.

Steve’s response was to shout angrily at me. “This isn’t my fault!” he yelled. “It’s your fault. This bio isn’t happening. Goodbye!” He hung up before allowing me to mollify him or perhaps reschedule.

After staring at my silent phone for a second, I wrote to the publicist. Never before or since have I written anything like that email, which said, as best as I can remember, “I am resigning from this bio assignment because your client just threw a tantrum over a minor technical issue and cut me off. Even your generous remuneration isn’t enough for me to put up with this kind of behavior.”

My publicist friend responded by recruiting the immensely skilled writer and scholar Robert K. Oermann to take my place. They seemed to get along well enough, given the quality of the bio they concocted. I can’t be sure, though, because I never heard from Steve’s publicist again.

####