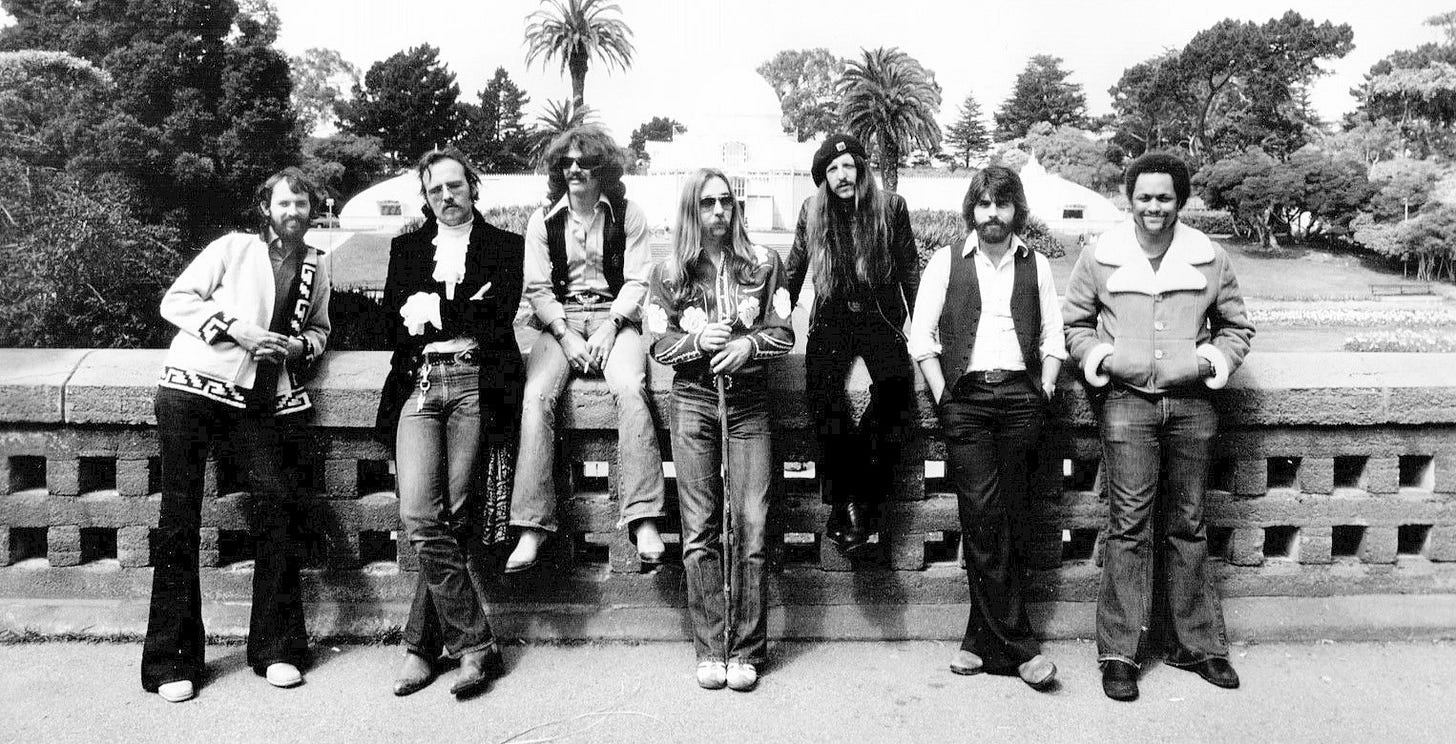

The Doobie Brothers

PR Bio, 2016

It was 2016 when I was called to do the Doobie Brothers’ PR bio. During the two or three seconds during which I pondered the assignment before accepting it, I realized that this would be different from anything I’d written that year. I ended up finishing nearly fifty bios that year alone, and almost all of them involved introducing new names to the media: Looking down my list, I see American Young, Insects vs. Robots, Moonshine Bandits, Radio Romance, Modern Inventors … bands that were either brand new or still clamoring for attention. All of the rest focused on individual artists. Most of them, too, were newbies; just a few were very well established: Tony Joe White, Gwen Stefani, Gerry Beckley.

Missing from the lineup were well-established bands, with this one exception. Which made this assignment unique: I had to to underscore their decades of mega-sales, huge crowds, massive hits and so on, while also making it clear that unlike many other groups of their longevity, they were doing something new, and that was what had to be underscored for every radio programmer, journalist and media icon.

Let’s be honest. Most rockers from the Doobies’ generation are either retired or playing their ancient tunes for audiences whose members gave up street drugs for Geritol long ago. Sadly but inevitably, they’re also dwindling in number. But having seen them perform on the Grand Ole Opry stage a few days earlier, I was impressed by the conviction the Doobies poured into their performances. They weren’t just phoning it in; they played like they were building their first fan base or auditioning for their first record contract.

I took notes as their publicist ran down what she needed: “They’re going through a renaissance, with a new generation of fans discovering them. It’s like the resurgence of Hall & Oates. Four generations attend their shows … Talk about what’s in their future. Ask about the writing they’re doing now … Ask about how they’ve changed over the years. Present them as a new band, in terms of their energy. … Get it done before they would launch their tour with Journey in a few weeks.”

And this bullet point: “Write this bio to position them for induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.”

It took another four years for that induction, so I guess I can’t claim much credit for that. But I think I delivered what they needed at the time.

***

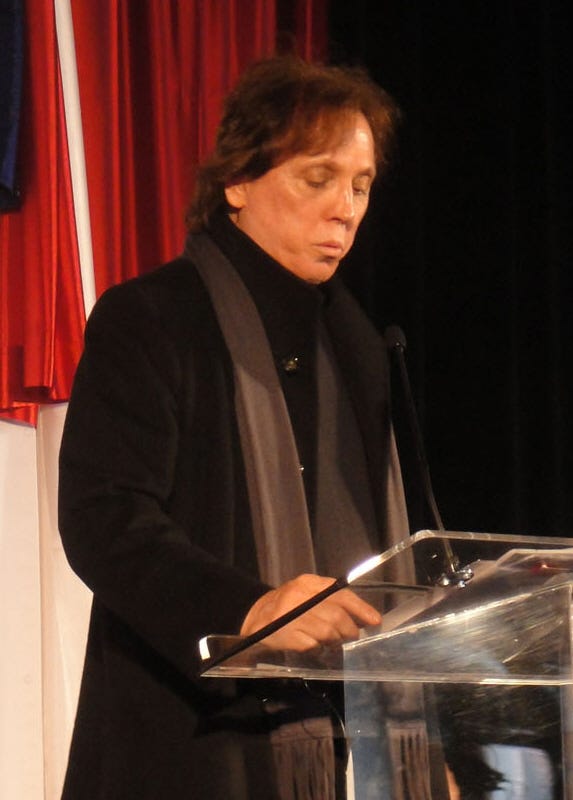

PAT SIMMONS

Let’s look at the Doobie Brothers as a contemporary band. You’ve got new music ahead of you. Can you compare where you are today with where the band was in its earliest days, what your dreams and goals were then and now?

It’s always been about songwriting and coming up with good songs. That’s still a priority, not in terms of something we feel like we have to do but something that we enjoy doing. That’s been the focus all these years, to come up with songs that are going to connect for the band and for the audience.

As you write new material, do you compete with your own history, with all the great songs everybody already knows?

There was a time that was true. I don’t think it’s as true anymore. This is probably the best part about growing old in the music business: Rather than trying to repeat what you’ve done or compete with yourself, it’s more about just coming up with something that feels good to you and that is real. When I say “real,” I mean something that’s not manufactured or tries to be commercial but is simply a good song in and of itself. I suspect that in the back of your head, subconsciously, that’s what you’re trying to do all the time. But more than ever these days, there are so many great songwriters and so much great music. More than anything, you want to be a part of that. You want to have a continuum, not in terms of competing but just writing a good song.

How has that process changed for you since the beginning of the band?

It hasn’t changed for me personally. I write on the guitar, for the most part. Sometimes I’ll write a riff and work off of that. Sometimes I come up with a series of chords and that stimulates something. Sometimes I write in my head and come up with a compelling lyrical idea. I’ll write that down and chase it with the music, looking for something that makes sense with that lyric.

Why have you been able to stay this creative for this long?

I don’t know! That’s a good question. I think it’s probably just something I want to do, something I enjoy. Some people lose their passion for music and move on to other things. I don’t see anything wrong with that necessarily because you really should be happy with what you’re doing. If it doesn’t move you anymore, that’s okay. There's nothing wrong with that. But we’re pretty committed to music and what we’re doing. There are times when those feelings drift. Sometimes you don’t feel as inspired. From 1983 until about ’87, we hung it up and went off and did other things. I didn’t let music go. I still played. I was still involved, doing things on my own and with other bands. But I just wanted to get away from what we were doing. At the time, everybody wanted to go in different directions. For me, it was kind of disheartening because I had felt that the music was going well. I understood that other people wanted to do other stuff but I was disappointed. And that disappointment made me less productive for a short time.

When we came back together, I wasn’t sure we would keep working. But I was happy because I’ve always felt good about the creativity in this band and how we create together. There’s something special about it. I was happy to circle back into it … and here we are!

Talk about the musical work you do on your own and how that compares or contrasts with what you do in the Doobie Brothers?

I’ve been with this band so long that I think in terms of when I’m working on stuff about how it’s going to work within the context of the band. I’m producing some stuff for my son Pat Simmons Jr. right now. That’s a total musical direction. But at the same time, I enlist some of my experience within this band to come up with ideas for his project. In a certain sense, it plays a part in my thinking in other areas. I think I learned a lot of good musical ideas from different people through the years. Working with Ted Templeman on and off for forty-plus years, I learned a lot of things about producing and songwriting that have really helped me through the years. I came to understand the process better. I give a lot of credit to Ted, especially because I was working with my son and would come against experiences that I had had in terms of the relationship of the songwriter/musician to the producer. It made me appreciate what I had learned from Ted because I was in his boat at different points, so his mentorship meant a lot to me. I carry it to this day really.

What are you learning from working with your son about his generation’s perspective?

Well, his music is a little different. It’s a little more alternative. Production values of the Seventies, Eighties and Nineties are different from the production values of modern music. He has in a certain sense a spiritual approach to the music. Less is more. I listen to Xavier Rudd and people like that, where production is a little less. In general, modern music uses a lot less reverb in certain instances. The vocals are more up-front and a little dryer. I hear that standard on a lot of records these days. It’s not a hundred percent, but you do hear it on a lot of records. Sometimes country music has more reverb going on. That concept of less production becomes important. Even if you have a lot of production, making it less obvious is the way to do it.

When the Doobie Brothers came together, what were your dreams? Could you have possibly imagined that you’d be where you are today?

We just wanted to get some gigs. I knew the guys from playing around town with John Hartman. They didn’t really have a bass player. It was kind of a rotating thing. I had been playing with some other guys, Tiran Porter being one. He ended up being the Doobie Brothers’ bass player. I had an acoustic act, which was Tiran, myself and a violin player. Then I’d go hang out with the guys and we’d jam from time to time. I didn’t feel comfortable committing myself to playing with Tom and John, which was more of an electric, hard-rocking band. I wasn’t sure at the time I wanted to do that.

Then, at some point after watching them play a few times, I made up my mind that I’d like to play with them. I just thought I really wanted to be a part of this. I really liked the music. I really liked Tom’s songs. I felt like I could add something to that. So I went over and had a talk, and they said, “Yeah, come on. Let’s do it.” We added a bass player, who I’d gone to high school with, Dave Shogren. The object was just to get some gigs and have some fun, maybe make a few bucks.

…

When you get in a room with the band today, how does the energy differ from the old days?

Well, for one thing, we were able to make much better home demos in the old days. I don't even know if we made demos. It was more like, “Here’s the song” and I would play it for the producer on guitar. You had to have a reel-to-reel tape recorder to record a demo and I didn’t have that. So anything I was able to offer was simply by sitting down and playing it for everyone. These days, we’ve all got home studios where you can go in and flesh out your ideas. So in a certain sense, our approach has changed. That’s how we do it these days: We’ll make home demos and play them for each other. Whatever songs we select, we’ll get a copy of that song so we’ll have a chance to work up ideas around it before we start rehearsing. That shortcuts the learning curve, which is a big help.

When you started out, you were playing mainly to kids your own age. Now your audiences span multiple generations. How has your relationship with your audience evolved? As it grew into the millions, did that make it harder to stay in touch with them?

It’s probably easier. It sounds like a cliché, but our audience is, like, eight to eighty, a lot of it because of the Internet. We all discovered older artists through the media in the old days. I was kind of a roots-music guy. I grew up listening to everything from folk blues to traditional music to modern rock ’n’ roll. When the blues made a huge resurgence, I discovered older artists. A lot of young people did. In a sense, that’s going on as well these days. I’ll go on the Internet and see or hear something. You can go directly to YouTube and find Muddy Waters. The same thing happens with us: People discover the band, start listening to our music and they like what we’re doing. Or maybe their parents listen to the music. They grew up hearing it and as they got older they realized they really liked it. You see parents come up with their kids, older folks coming with their grown children. Music is one of those timeless things that people enjoy at any age. We’ve been lucky enough to tap into that. With Facebook, we’re able to have a direct contact with thousands of people. At any given time, I’ll go on there and I’ll see who’s checking us out. That network brings people closer together. It’s easier to be a part of fans these days.

We’ve always had a fan club. In the not-distant past, I used to meet people after the show every night. People would come and I’d shake their hands and talk to them. It got a little bit fatiguing for me and I haven’t done it as much because it got to be too much. So Facebook is a great way to stay in contact. I think that’s a motivation for young people to go, “I’d better see these guys before they hang it up [laughs].”

“We’re a better band than we were when we were younger because we care about it more.” — Patrick Simmons

Really, we have a great band. In reality, I think we’re a better band than we were when we were younger because we care about it more. The technology, the amplification in live situations, is so much better now. The P.A.s are better. The way we approach performance is better. We don’t need to have the amps blaring really loud on the stage: They’re loud but we have them baffled. They’re miked strategically so it sounds more like a studio recording in some ways. That’s much better for the audience and for us too because we’re able to hear ourselves and sing better. But we also care more about it. We warm up before we sing. We don’t get drunk and stoned; That helps a lot [laughs].

…

Does the band still look ahead with specific goals?

We have ideas we’d like to experiment with — things we haven’t done before. We’ve talked about doing complete albums back-to-back, all the songs the way they were recorded. We’re going into rehearsals. We’d like to do some performances with some additional musical guests, perhaps some orchestration with string players and horn players — a larger ensemble. We haven’t done very much of those but we’d like to perhaps do a series of performances in a single smaller venue over four or five days and perhaps other musical guests sitting in with us.

TOM JOHNSTON

How has the process of working out new material changed since the band’s earliest days?

We’re probably going to do another project after we finish touring. At this point, everybody’s looking at touring right now. But as to methods in which we do the creating, I’d say that’s changed. In the old days you’d come up with a song on a guitar and bring it in and everybody would fill in the parts, if you will, and come up with ideas. You would add singing and chord changes and that was it.

…

I’ve also been writing with people in Nashville. It used to be that I never wrote with anybody. Because you write with two or three people in Nashville, it’s a new experience. It’s an education. They give me the lyrics right away. My habit is to get the track done and then I start writing the words. But they start writing the words as soon as you’ve got chord changes for the verse. It’s a good way to do it. If you’ve got two or three people, then the ideas for the lyrics come flowing and you take the stuff you wouldn’t have thought of by yourself. So that part of the song changed for me.

Who are some of the writers you’ve been working with in Nashville?

Jeffrey Steele, Bob Di Piero, Chuck Jones … Most recently I wrote with Paul Overstreet. That’s pretty much everybody I’ve worked with in Nashville. I haven’t done it a lot; I’m still dipping my toes in the water.

Has co-writing affected how you write on your own?

It probably has. I haven’t been real conscious of it because I haven’t done a ton of it because we’ve been working. The most recent writing I’ve done has been with Bill Payne. But it gets me to start thinking about lyrics a lot earlier. That’s a good thing because lyrics have always just happened. The songs that write themselves are always the best songs to me. You don’t have to labor over them; they just come. There are times in your life where something will unlock that key and all this stuff will come floating out. You have no idea where it comes from — but you don’t ask any questions [laughs]. You just go with it. Those are the best songs.

When the Doobie Brothers came together, what were your dreams and motivations?

For me, it was just the joy of playing. I just loved playing music. I didn’t expect to make it in the music business. I played all the time with a lot of people before the Doobies. When the band started playing together, we wrote songs as a group after the original chord after the original chords came in. We were playing clubs. The guy who was most into making it in the biz was our drummer John Hartman. The rest of us didn’t really talk about it a great deal. We just played. There was a big music scene in the Bay Area. It was just fun to be a part of it. It was almost like a hang. But we worked hard at it, even though we still sounded like a garage band [laughs].

Over the years that changed just from working with professionals in the business once we did get signed. Of course, doing all those albums with Ted Templeman and Don Randi and other people after that. Everybody has learned so much over the years about everything from playing live to writing songs to having experiences to pull from. But it’s odd because when you’re at that stage of the game in your early days, there are no walls or rules. You just do it. And you don’t really care. You just want to play. The joy and the fun of it just took over.

“In the old days, we just played. When I got off the road, I didn’t go home and practice or think about it. Nowadays, I practice religiously.” — Tom Johnston

The band has taken playing live to several other levels by now. We all practice. In the old days, we just played. When I got off the road, I didn’t go home and practice or think about it. Nowadays, I practice religiously.

Audiences today have much higher expectations for live performances.

That’s the truth! We’re not ever gonna have people dancing and doing things like that. We still go up and just play. That’s never going to change. And that’s fine with me. That’s what we’re all about. And it works!

Nowadays, playing for crowds, especially in a festival atmosphere as opposed to a small theater, you find a much younger audience. I’ve spoken with a few of them, not long conversations, but they’ve picked us up on streaming and downloading. They didn’t pick it up from their parents or any other stuff, which used to be the case. Or back in the day, they were picking it up because it was on the radio and they heard the songs. It’s very gratifying to find that people enjoy the music we make from back then up until now. They just enjoy what the band is about, and that’s all ages.

The energy has kind of stayed consistent in one fashion, and that is, it’s up. They’re not just there, looking at you. They’re involved with the show too. To me, they’re as much a part of the show as we are. We’ve got to put out the music to turn the key, but after that they’re dancing and they’re singing. That’s a huge part of what energizes everybody onstage. That interaction between the band and the audience is what it’s all about if you’re gonna play love. And I absolutely love it.

We’re not putting out an album a year, like we did in the Seventies. But we are gonna be doing some new work. We want it to be the best work that it can be. Getting it out there nowadays is so different from what it used to be. Everything in the music business has changed, top to bottom. Unless you’re Taylor Swift or someone like that, you don’t sell a lot of albums because you can get it on streaming or download whatever song you want without buying the whole thing. CDs are going away.

…

How have these changes affected the Doobie Brothers positively and negatively?

Truthfully, I don’t think we’ve changed that much. You could talk about using loops on a song or something like that, but as far as how we approach it in the studio, it really hasn’t changed that much. We still go in and do the same things we always did. We cut the basic, then we do the overdubs. Certain people come up with an idea to complement the song.

You’re generating new stuff and continuing to challenge yourselves and writers and players, even though you’ve got this gigantic body of work that everybody knows. That sets a high bar for you to meet when you’re doing new material.

To a point that’s true, not so much stylistically but you want it to be as good as those songs were when they came out and to have staying power. You don’t want it to be, “OK, they have a new album. They did some songs. It’s those guys again.” You want it to be something that people will hear and like. Writing songs is a challenge anyhow. You always want good songs. You want to bring out the best of yourself. You want it to resonate with the people you’re playing for. I can’t speak for the other guys in the band, but I don’t look at it as a way to elongate our time. We don’t necessarily change our musical style to be popular right now in whatever genre. We’re still a rock ’n’ roll band but our rock ’n’ roll has Americana, blues, R&B and some bluegrass in it. We’ve always been that. We’ve never been anything else. That’s probably a plus.

Americana has helped lower barriers and open people’s ears to bands like the Doobie Brothers, whose sounds are so eclectic.

I think so too. These festivals are a great vessel for bringing music to large quantities of people. I hear people I’d never heard before who are combining a lot of styles in a lot of instances. It’s sort of the same idea. Music is not as solidified here as it ought to be: “Here’s rock ’n’ roll, here’s R&B,” and frankly there is no [unintelligible] that’s strictly rock anymore. Country music has taken on rock ’n’ roll. It’s kind of like classic rock but they put country [sounds like: words? licks?] over the top of it. It’s not the country music of George Jones and Tammy Wynette at all. And you don’t really hear the original R&B. Aretha Franklin and those types of people, it’s not going on anymore. Rap has taken its place.

Why have the Doobie Brothers stayed fresh?

I have to say it’s playing live. It’s really imperative for us to put on a good stage show. That trends in over to when we get into the studio [?]. We don’t want to rest on our laurels and just play oldies. Sure, we play the chestnuts because we have to — people really want to hear them. The pleasure is the response you get when you do it because every night you play to a different crowd. You get a different version to that response. That’s why we change up our set. You usually have a specific time frame in which you have to do that. In this case we’re going out with Journey; they’re the top bill. We’re going to play 75 minutes; if we were playing ninety minutes we’d have a lot more latitude as far as how many songs we throw in from out of the catalog, not including the album we did for Sony with all the country artists. That was a great album but it was redoing old songs. I don’t think of that as a trade studio album in that sense. But I’ve got to tell you, those guys that we played with? God, they’re good! They blew my mind. We’d worked with studio guys but never en masse like that. They were the band. They blew my mind. The producer, David Huff, came up with them; they were all studio guys from Nashville.

Will you be recording the next one in Nashville?

I don’t know anything about that right now.

You were terrific at the Grand Ole Opry.

That was a fun night! I really didn’t know what to expect. We were all really humbled by the crowd’s response. That's a sacred country venue. We’re not a country band but part of that is there in some of our stuff as long ago as ’72 or ’73.

JOHN MCFEE

Does it feel different to be with the Doobie Brothers these days than it did in your earliest days of involvement?

With the passage of time, one thing that’s kicked in is that, believe it or not, I think we have matured [laughs], at least to the extent that we really appreciate how lucky we are to be doing what we do. We always have but I think it’s more so now than ever how unique and special it is to have guys that actually like each other and like playing music together — and we have a pretty fair portion of the public that likes the music too [laughs]. More than ever, we appreciate all that. That’s one big difference.

We’ve learned how to focus better onstage. At this point, we have to work on staying in shape and staying healthy and stuff like that. When you’re younger, you don’t think about that stuff so much. I’d like to think that we’ve gotten better and that I’ve expanded my musical knowledge and my chops. If we were working on new material now, I like to think I could come up with better parts, with more depth in my playing and writing. The band has always been good, so it’s kind of like we’re competing with the younger Doobie Brothers [laughs] because so much good stuff has happened. Honestly, we might be playing better than ever. It’s never been on autopilot. We work hard for our money. We feel an obligation to deliver. And we like what we do. We wouldn’t be doing it if we didn’t believe in doing music. That’s another thing. We put as much energy into it now as we did when we were young if not more because of all those factors.

As you’re putting stuff together, do you feel competitive with your own reputation as far as meeting audience expectations?

I can only speak for myself, but it certainly crosses my mind from time to time. But you can’t get hung up on that. You’ve just got to be the best you can be at this point in time and now be too worried about recreating something from years ago other than through doing your best. For any musician, that’s how to look at that challenge: just do your best and use whatever you’ve accumulated in terms of knowledge and chops — and do your best.

How do you structure your live set, so that you present both the classics as well as new material?

That’s always been an issue. When the band was introducing Michael McDonald and a whole new sound, it was a tricky thing. You always want to deliver a certain amount of the material that people expect to hear. In the case of the Doobie Brothers, it's almost made more difficult by having so many hits. Depending on how long your set is, you can put only so many new things in without people going, ‘Wow, they didn’t even play this or that.’ You don’t want to disappoint your fans but you do want to keep being creative and hope that they’re willing to at least come along with you a little ways. That’s always been the case. You can’t just sit back and rest on your laurels. So there is a percentage as to how much unfamiliar material you can get away with including in your set — I’m just not sure what it is.

What goals does the band still have?

Goal Number One is to make the best music you can possibly come up with. We’d like to be appreciated and recognized, not to sound too much like Great Expectations [laughs]. But it would be nice, for example, to have something pop out in a way that got a lot of attention and airplay and on the Internet and on television. But again, it’s always been about the music.

“I’m still the new guy because I’ve only been here 37 or 38 years.” — John McFee

Could you have imagined, in the early days, that you’d be doing an interview like this forty years in the future?

It’s pretty amazing. I’m still the new guy because I’ve only been here 37 or 38 years [laughs]. But whoever thought about having a career this long? I didn’t! When I played with other bands, it was unheard of. When the Beatles came out in 1964, for example, who was the great musical artist of 1924 that people still wanted to hear? But we still have a great following. We are so lucky. I couldn’t have foreseen that.

In the beginning, bands play pretty much to their peers. Now you’re playing to maybe three generations of knowledgeable fans. How does that feel different to you?

I’ve been seeing a shift in the past ten years with YouTube and the Internet. Some kids got turned onto the band by the parents or whatever in the early days — it could be their grandparents [laughs]. But there’s a certain amount of realization that’s happening with younger people. That’s one plus side of the Internet. There are perhaps plenty of negative sides. Butt’s cool that there are younger people who do feel like that. Sometimes they’re surprised that it’s ancient stuff [laughs]. “That’s from that many years ago? But it sounds so fresh!” To them, it’s new music. It’s competing with whatever other music they’re hearing. We played Stagecoach the other night, and these young kids were singing the lyrics. It was just amazing.

One cool thing about joining the Doobies was that I’d always admired the band because they were always experimenting. One song would be more country-influenced and other songs, like ‘Long Train Running,’ were more R&B-influenced. McDonald brought more of a jazz influence. It was all wide open. I always felt like this was such a great band and that it would be fun to play with them. Then I ended up joining the band! I never felt I had to change my style that much. I’m still trying to extend and improve as a musician.

…

How does this band stay vital and fresh, as opposed to becoming an oldies act?

I guess that having a similar work ethic is one reason why Tom, Pat and I are still surging ahead and have stayed together and are friends and get along as people as well as musically. We are compelled to challenge ourselves. I mean, I love playing the old songs. They never get boring. We often get asked how it feels to play the same songs night after night. The only thing I can say is, ‘Well, it’s not the same. It’s a different version every night.’

So if you’re doing something with a guitar solo everyone remembers from a long time ago, you’ll jam on it rather than replicate the solo.

Exactly, stuff like that. Even trying to play the same part, you’re always motivated by the moment and you put something different every time. At least I do, you know? Even the old material doesn’t get stale. And we rearrange songs from time to time. In a lot of ways, this band is motivated to keep things fresh.

Do you write a different type of lyric nowadays than you might have twenty or thirty years ago?

To me, good writing is honest writing. I don’t think you should avoid being honest about who you are and what you’re thinking. But that changes over time. We are not exactly the same people we were all those years ago, although in a lot of ways we are. So who knows? Others might have better judgment about [unintelligible], the lyrics and stuff like that. For me, lyrics are always challenging anyway. Almost everything has already been said; it’s just how you say it. It’s always about finding a new angle on saying whatever the thought is about. People have been around a long time — a lot of great writers or prose, poetry and musical lyrics. So I’m not so sure a totally new concept comes out very often. So a lot of it is about your angle on the human condition. That’s always a challenge to find something that’s honest and meaningful and that others can understand without getting out a dictionary [laughs].

Even just using the word “challenge” answers the question. It’s not about repeating yourself.

####