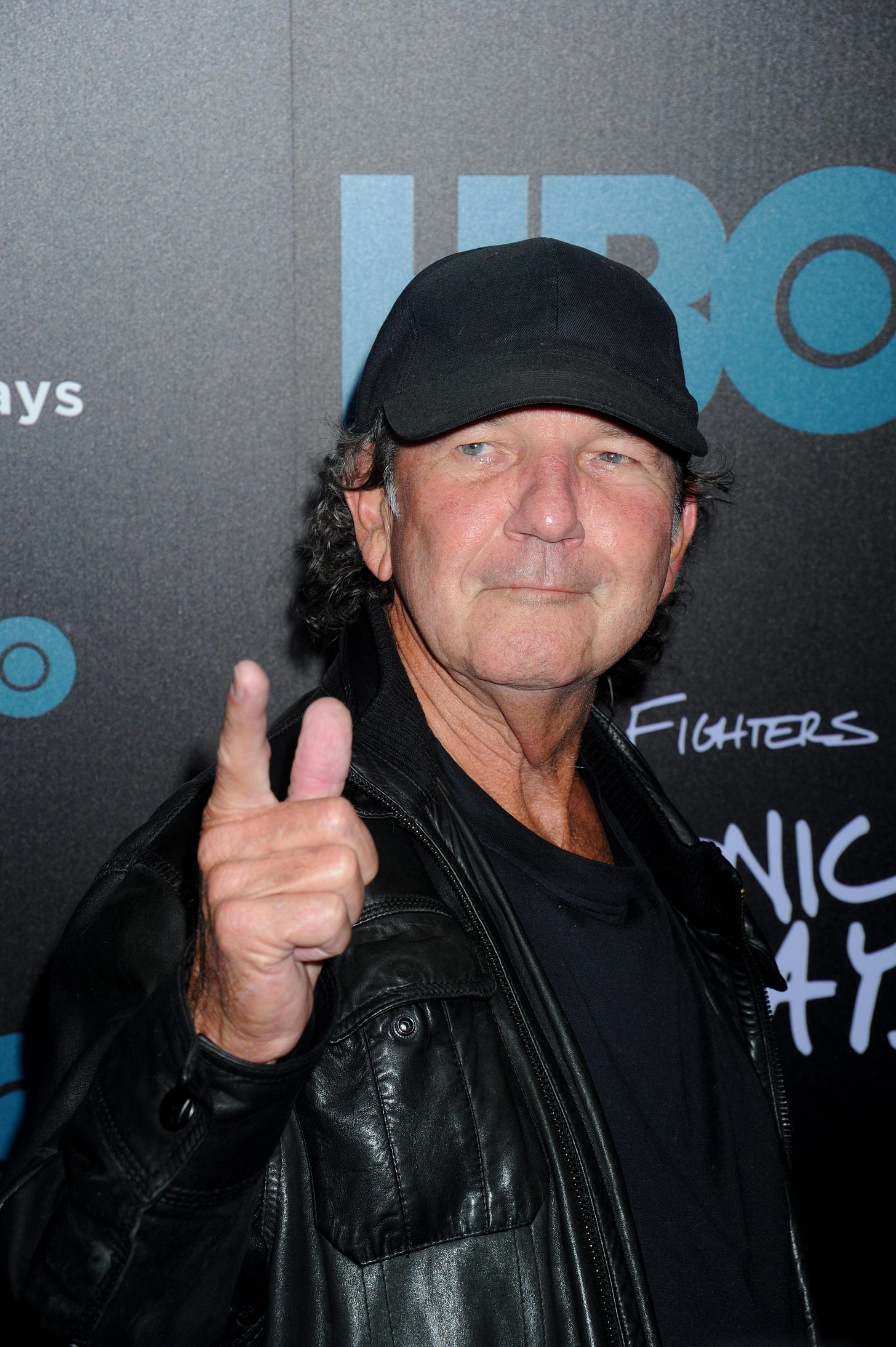

Tony Joe White

Nashville Rage, Date TBD

When I think of the late Tony Joe White, ghosts come to mind. Not the kind that terrifies families in Amityville, or slimes Bill Murray, or that “children love the most” in the Casper cartoons.

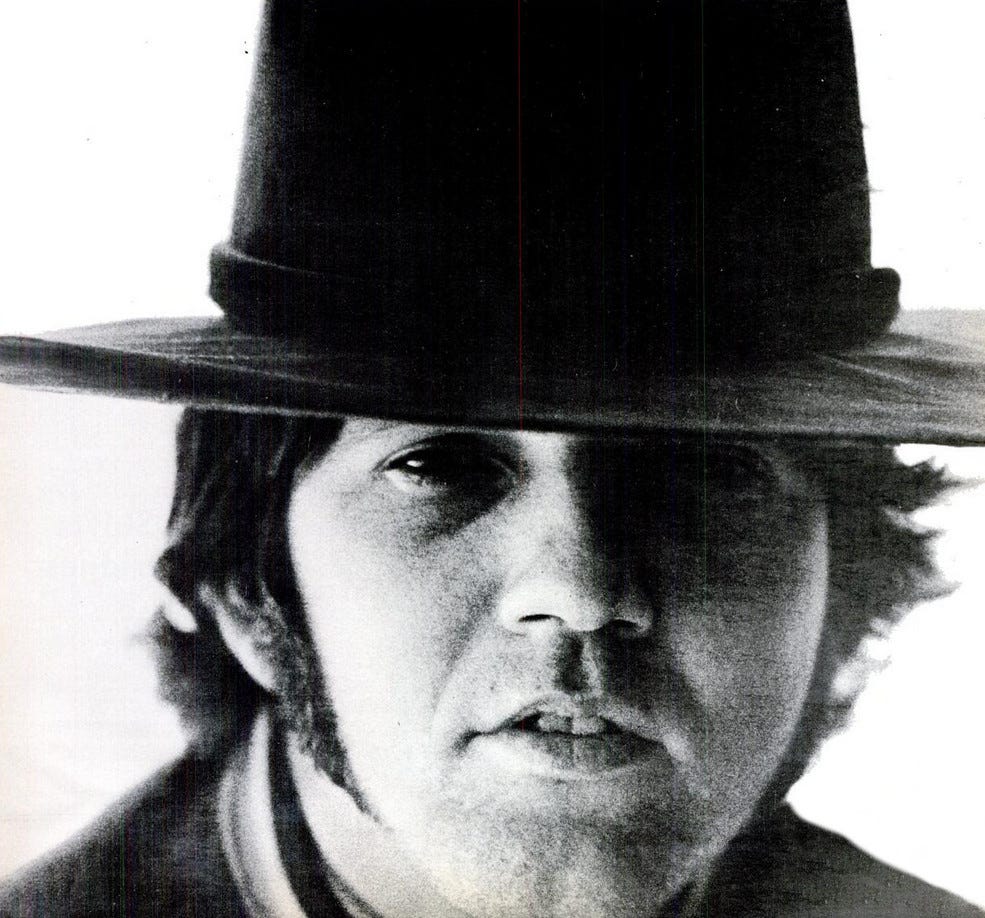

No, something deeper, less anthropomorphic, haunts White’s music. Often his songs reference flickering fire in darkness, shadows and spirits. He came from Louisiana, you see, and he tapped the power of these mysteries as he broke into the pop music charts sixty years ago. His first and biggest hit, “Polk Salad Annie,” presented White as a unique artist for the times: deeply steeped in the culture of backwater Louisiana, where dinner was often“poke sallet,” made from a poisonous weed made edible if prepared correctly before the heat of summer settled in. For poor families, it was a vital food source; for White, it was also a symbol of the hardscrabble life he knew in West Carroll Parish.

In 1969, when “Polk Salad Annie” brought White into the spotlight, the blues was well established as an inspiration for many young rock artists. But their music often emphasized virtuosity over literalism, particularly among English performers such as Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck and Peter Green. What resulted was often exciting, born not from authenticity but from an interaction between American and British elements.

White, on the other hand, knew the birthplace of the blues intimately, having picked cotton in the same fields that nurtured the music of Charley Patton, Mississippi John Hurt, Son House and hundreds more whose names, if ever known, are now lost. He wasn’t replicating their work, though, but personalizing it, drawing not from the outside but from the world he knew first-hand.

In the later stages of his career, I interviewed TJ three times, once for the now defunct Nashville Rage and twice for PR bios. The latter two were tagged to The Heroines (2004), a celebration of female artists, and Rain Crow (2016). By this point, the blues roots of his music had simmered into an idiosyncratic brew, earthy and mysterious. Most of his songs sat on just one chord, over chilling mists or chugging grooves; his lyrics, and his whispery vocals, completed the spell.

We did our interviews at his studio, a few blocks from the town square in Franklin, Tennessee. There was no signage in front, just a scraggly little yard and a weathered exterior. Like much of Franklin, this building was more than a century old; the living room had high ceilings, faded wallpaper, dark hard-wood floors, a fireplace and a beautiful chandelier. The place had been used during the Battle of Franklin, as a field hospital for wounded Union soldiers, as I recall. Somehow the place survived the Civil War as well as the devastating flood of 2010.

“We were so lucky because right under where we’re sitting now is a fourteen-foot-deep basement,” White explained. “It’s all rock and stone. The water was this far from these floors where we’re sitting when the flood came. All my guitars, equipment, tape, all my lifetime of music is in this one room. If it rose eight more inches, it would have floated down Church Street. It took a week for them to get that pumped out and then two or three more weeks with fans. I got in there with some brooms and Clorox.”

“Does the studio have a name?” I asked.

He chuckled, like a cat’s purr. “My son Jody and I just call it the Swamp.”

Of course they did.

One last memory. Twice, after leaving the Swamp, I got halfway to my car and remembered I’d left something inside. I turned back and knocked on the front door. A woman I hadn’t seen previously, opened it. I explained what had happened and was let in to retrieve whatever it was. Come on in, she said. Not one minute had passed since I’d shaken TJ’s hand and said goodbye, yet the living room — the whole house, as far as I can see — was empty.

“Where’s Tony Joe?”

She smiled. “Oh, he’s … gone.”

****

Is that how you feel when you go back to Louisiana? Does that still feel like home to you?

Too much time has passed, but my folks and all my sisters and brothers, they all still live down there. When I go down there we're busy fishin' and cookin' up the fish and hanging' out by the fire and bustin' out the guitars too, around the fire. I don't miss a whole lot about it. It's changed a lot from when I used to live down there, but it's still the same when you got your blood around you and everybody's into the music, playin' and singin'. So we stay busy when I go down there. I don't really go to the river and stand there and wish it was this way or that way no more. We usually do something.

Does your family still grow cotton?

No, everybody moved off from the cotton farms. When I left and went to Georgia it was already changing.

You did a lot of hard work in the fields down there. Maybe it's hard to be nostalgic for that.

There's nothin' harder than choppin' or pickin' cotton. But there were people singin' in the fields. There was a lot of black people down in that part of the country. You'd go over to their house at night, sit out on the porch, play and sing, and stuff like that, and all of a sudden the day would wash off of you. Or you'd go to the river and swim, hang out, dive off the trees, and that kind of thing. It wasn't fast; it was a real syrupy kind of movement in time.

And it wasn't divided into black and white.

That's it. We never thought about that at all. We all worked together in fields. We played music together. We didn't have no problems with none of that.

That hard work fed your music with a lot of feeling and soul when you got out of there.

I don't think I could have done none of this … Well, I know I couldn't have, because most of those characters, like the High Sheriff and Old Man Willis and Polk Salad Annie and Widow Wembley, all them people lived around there. I knew them. They were real people. The songs are real. Without all that, I don't know how I'd ever have started writing.

Were you raised speaking French?

I was raised up in the Delta end, on a little cotton farm at a place called Goodwill, Louisiana. Up there the food is different, the music is different, the whole thing is different — language and all. So I never learned any French growing up in Louisiana. But the French they've got down there is a little different anyway. There's so much good stuff to eat down there, you don't worry about talking.

Did you have a musical family?

There were seven kids in our family: Mom and Dad, an older brother, and then five girls between him and me; I was the youngest. They all played guitar and piano. After you pick cotton or work all day in the fields, that was your thing. So I'd sit on the porch, listening to them play. It was mostly gospel, country fiddle, and stuff. I never did really get into the music at all until my brother brought home an album by Lightnin' Hopkins. I heard that old blues thing, just a guy and his guitar and his foot, and that turned me around, man. I was about fifteen when it hit me.

Do you get back to Louisiana that often?

Yeah, I still got a lot of family down there. My sister Shirley, she lives there on the Bayou in a place called Mer Rouge, 10 miles from Goodwill where I grew up. My other sister, Frieda, she’s up here; she runs the boat dock on Percy Priest Lake. They both play and sing about as pretty as you want to hear. They can harmonize. Every time I go down, they break the guitars out. Usually I go down two or three times a year.

Have you recorded with them?

We have put a few things down.

When did your voice change?

Well, right now you can’t hardly tell because of this head cold. When I listen to it right now, it sounds like I'm about two steps up where it usually is. I think I was around 15. It was when I first started sneaking my dad’s guitar up to my bedroom. I’d play on it and kind of hum along with licks and stuff. I noticed back then it was dropping. My voice really has so much to do with it. I was just coming out of high school, playing the clubs in Monroe, Louisiana, and down to Texas. I was doing a lot of Elvis songs. When I listen back now, his voice was a lot higher than mine but it had that long tension in it. But between the blues artists and everybody, I would say it headed more toward John Lee than anyone.

Europe is almost like a second home for you.

Yeah, things kind of kicked off over here for me even before 'Polk Salad Annie' with a song in France that was in the Top Five. People stay with you through the years. It seems like I'm not getting to play very much in America, but I've been over in Europe and Australia for the past several years.

Have you noticed any changes in how American artists are received these days in Europe?

No, not at all. In fact, it seems better to me, these past several years when I come over here and play. When I first came to Paris, with that hit record, they asked me not to come out of the hotel and walk around too much at night, because they was burnin' the flag in the streets at that time. It was during the Vietnam war days. But the people who come to [sounds like: seem these chicks] come to hear swamp and play a guitar and get steamy. They know it's going to be swampy; that's why they come.

When you come back to the States, do you think Americans are misreading Europeans these days?

That might be. I'd say that anybody who came over here, Americans or whatever, wouldn't feel too much of a change from the way it's always been. There don't seem to be no real uproar about them joining us or whatever.

How does it feel to not be booked as much as you'd like in the States?

The last two or three years I've been doing more shows in America on account of the website, emails and things. I have my son Jody working with me the last few years. We played a good bit in America last year: New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Texas. So it doesn't frustrate me. It's cool that you've got someone anywhere that cares about you.

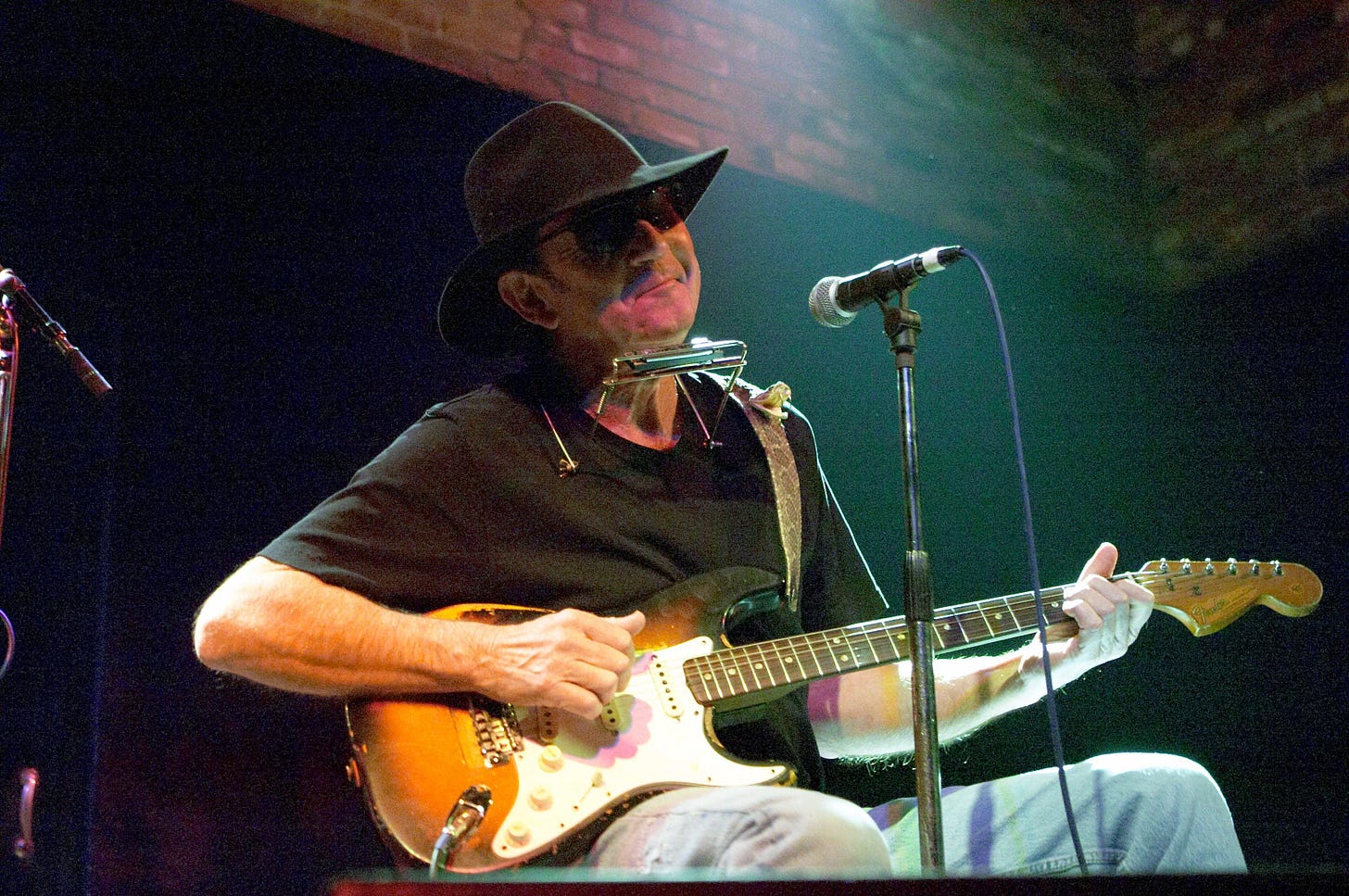

Are most of the people you’re playing for longtime fans?

We got a lot of young kids coming to the festivals and shows. They're into the realness of the thing, because onstage I just play with drums, my guitar, and me. There's no band or nothin', so they're able to hear the back porch version.

Why don't you even have a bass player?

I play so much bass on my guitar that it fills it up real good. Then I can also [unintelligible] the crowd as soon as you walk onstage, hollering out all these old tunes from the early albums. So I can jump on requests from back to Black and White [debut album, 1968] to the newest album. That way you don't have to turn around and tell the organ player or the sax what key. It's just me and drums, and it works good.

Lightnin' Hopkins used to play with just a drummer.

Lightnin' did it, and I did it all through the years in Louisiana and Texas. I have more freedom when I play that way. I play more guitar. I get more into the song; instead of listening to three or four people onstage I'm listening to what I'm doing.

You can hear Lightnin' in what you do even now.

Yeah, my guitar especially.

You listened to John Lee Hooker too.

I'll tell you what it was. It was Lightnin' first, it was John Lee, Muddy Waters, and then Jimmy Reed a little bit later on. And then Elvis came along; I got to doing some of his stuff onstage in Texas and places like that. He was kind of a bluesy type in his voice. He fit right in, because most all of us teenagers around the river down there, all we listened to was blues.

Those blues guys tended to play the blues on the I chord, rather than change to the IV and V.

Some of them didn't move at all. They just tuned it open and stayed in one key. But Lightnin' could move around and do some things. John Lee, he didn't move a lot at all, but when he played it meant something. He'd sit there and let his band rock for thirty minutes, and then he'd lay into some kind of a lick and make everybody lose their minds.

That lets you hang onto one chord if you feel like it, or get off of it whenever you like.

Each time, our drummer never knows what "Polk Salad Annie" or even "A Rainy Night In Georgia" is going to sound like. I do 'em different every night. You have that freedom when there's just two of you -- otherwise you'd have to do the same show every night.

Who is your drummer?

It's Jack Bruno. He lives in Franklin. He plays a lot with Joe Cocker, Tina Turner, and me. He's a great drummer.

What attracts you to the idea of writing songs that just stick on one chord, beginning to end?

If you’re lucky with it, it’s a chant that happens. If you just stay there and don’t jump around or flash a lot of licks, a chant will show up. And when that shows up, you’ve got something. And you’re right: John Lee and Lightnin’ did it forever. I move around here and there when I need to, but I really like the idea of simplicity.

You moved to the Nashville area a while ago, but you don't keep a high profile in this town. What brought you here?

When I first came up, which was maybe sixteen, seventeen years ago, maybe more, I had maybe two or three songs wrote and I drove up from Corpus Christi, Texas. I was thinking about Memphis first, but for some reason I just kept on driving and I came to Nashville. Walking around the city that afternoon, talking to different people and stuff, they kept telling me I drove a long ways for nothing. So I went to a club that night and listened to a band, and I met a guy that knew a guy that had a telephone number, and all of a sudden the next day I was in Bob Beckham's publishing company office. He said, 'You drove all that far to play me a song?' I said yeah. I had a piece of 'Rainy Night' wrote, and I had all of 'Polk' wrote. I just played him them two tunes. He said, 'Come in here with me to the studio, man. Let's see how you sound on tape.' It was just acoustic guitar and me. As it turns out, he was probably the only man in town at that time that would have listened to something that funky.

If you have to pick between Memphis and Nashville, your music does have more of a Memphis quality.

I guess so. I lived in Memphis, but all my stuff kept happening in Nashville: my recording, the publishing company, the record company, and everything. I've always been there but I've never really been a part of the actual scene in Nashville, except the underneath part, where the artists are. I play with a lot of artists there, and they record a lot of my songs.

How has Nashville changed for you over the years?

It seems to be a lot more open. A lot more people are coming in there. In fact, where I live, in Leiper's Fork, there's nothing but rock & roll people and blues players out there — Michael McDonald and people like that. It seems like everybody wants to come there. I don't know why, but I'm glad they're all there.

The music scene is getting more diverse here, with artists who owe a debt to your music.

Yeah. When I play there, wherever I play, the clubs or whatever, the crowds are right there with you. They know the songs. In fact, a lot of people in the audience have ordered the album from Europe. We stopped that with the website thing, and people can get anything I've got now off of that. I've never been treated like a downer thing in Nashville. It's always been great when I play there. I've never been into the record scene there, 'cause I was usually signed somewhere else. But I just like to live there. It's got everything we need.

How do you feel about the Americana movement?

It's real good, man. They just seem to be coming into music. That's why we went with this record company. Sanctuary is heavily into songs and songwriters and rawness, that kind of stuff.

A lot of the traditional business in Nashville is about selling product, and these folks do seem more interested in doing good songs based on real life.

Exactly, that's it. It was always that way here. Even back when I did 'Polk' there was a marketing talk with Monument Records. I was like, 'What's marketing? I don't know nothin' about that.' I watched through the years, kept going and going, and all of a sudden, the last several years it's almost like the Detroit assembly line. You can't get music where you got to set it free somewhere. I guess that's why a lot of them are doing a little bluesier and funkier feelin' [sounds like: team].

When did you last play in Nashville?

I played at 3rd and Lindsley last year. Every time I play there Lucinda [Williams] comes and digs it; luckily she was off tour. She comes backstage and we hang out. It's always packed there. In fact, it's fire marshal time. We're going to have a record release night at B. B. King's club on that Americana week -- the 24th, the 26th, whatever night that is. We're going to do a whole set, just me and my drummer. I think Shelby [Lynne] will be there, and Emmylou [Harris] might show up.

When you write songs, do you have to wait for them to come to you, or can you do a writing session and make something happen?

It has to come to me, the guitar and words. A song will start coming to me, maybe a guitar lick or a title or a line, and I'll take it the way I feel like it ought to go and try to be truthful and not try to direct it toward the radio or any kind of Billboard magazine or none of that. I just write the song. And all of a sudden, when it's finished and you're sitting there by the fire, you play it to yourself, and if it flows good, then you know you did it right.

“All of a sudden, a little light goes off in my head, a guitar chord will pop up, and here we go.”

Leann [Tony Joe’s wife], she’s a real word person. She don’t play any instruments but she’s a great writer. She’ll say, “What do you think about this or that?” And all of a sudden, a little light goes off in my head, a guitar chord will pop up, and here we go, writing one. But as far as writing myself, it’s usually, like I said before, a campfire down by the river and a few cold beers. I’ll sit there, strum a little bit, and all of a sudden a lick will come. I’ll leave it alone for a couple of days.

Do ideas come to you when you’re half asleep, so you have to get up and write it down?

Yes, through the years, many times at two or three in the morning, I’ll get not a whole song but something I want to make sure it’s cool enough to come by your bed, tap on your foot, and make you get up and write it down. Usually, the next day, I’m really glad I wrote it down.

Does it ever happen that you can’t figure out the next day what that idea was all about?

No, I haven’t had that particular type of thing. I’ve had it where it took a while to figure out what I wrote because my writing was funky; I’d had a couple of six-packs and went to bed [laughs]. But usually, when I jot something down in the night, something good happens with it.

Music today lacks this sense of magic and mystery. You are one of the few writers to have been there, lived there and breathed it in. Your magic is undiminished.

That’s cool with me because it’s all given to me anyway.

There was a boy about seventeen in Sweden. He come up after the show. He says, “You saved my life last night.” I said, “I didn’t play here last night.” He said, “I’m talking about in my house. I was just getting ready to do it, man. I put on my favorite record.” I said, “You was fixing to do yourself in and you heard a tune and stopped it?” We hugged each other, took a picture together and he walked off.

Beautiful, TJ. I think we’re done.

It’s really good, the way you covered it, because for me it was a soulful type of thing. Thank you, man.

####

I saw Tony back in Toronto in the late 60's ,a soulful singer who cut to the bone of the song ,no frills just a funky backbeat and simple straight ahead lyric,he was on stage by himself,now this was on a bill with a lot of loud brash rock bands being the era and all,he made a impresssion on that young man,who thought if you you don't need lights,volume and makeup ,just a good soul and a large dolp of Soul..........thanks for this.