It’s hard to believe, but the first superstars of music weren’t four lads from Liverpool, or a hip-swiveling Southern boy or a New Jersey crooner. Their ancestors actually stretch back some two hundred years, arguably to a violinist whose virtuosity and vaguely sinister charisma provoked swoons and shrieks not unlike what we witness nowadays at Taylor Swift concerts.

That violinist, Niccolò Paganini, set the stage for similarly heroic instrumentalists. For some reason, pianists in particular resonated in the popular imagination, especially three whose romantic appeal arguably counted for more than their musicianship — not so much with the first of these, Franz Liszt, whose compositions were as significant, and more enduring, than the impact he made while performing them. This, plus his long hair and dramatic flair, his daring performances purely from memory, even his invention the solo piano recital, ignited hyper-emotional responses: female worshipers throwing fan letters onto the stage, fighting in the street for his discarded cigars and, inevitably, enterprising businessmen monetizing the phenomenon by selling lithographs, brooches and cameos adorned by his noble profile.

Several decades later, a successor arose in the form of Ignace Jan Paderewski. His hair was Lisztian, his visage poetic — and, again, his largely female fan base exuberant in expressing its devotion. Unlike Liszt, the young Polish pianist wasn’t always comfortable with this idolatry; on occasion he would even scold attendees for not taking him seriously. But like it or not, Paderewski had no trouble taking Liszt’s place in the pianistic pantheon.

In an article on the Polish website culture.pl, historian Ludwik Stomma described the scene when the pianist arrived at the venue hours before the recital began: “The crowd was taken over by hysteria. Young townswomen of London … were now pushing toward the staircase, trampling each other, and shouting, ‘Take us! We belong to you! We are yours!’ Next, they pulled up their skirts to reveal frivolous underwear with the name of their idol embroidered next to a red heart. For the sake of public morals, the police had to intervene.”

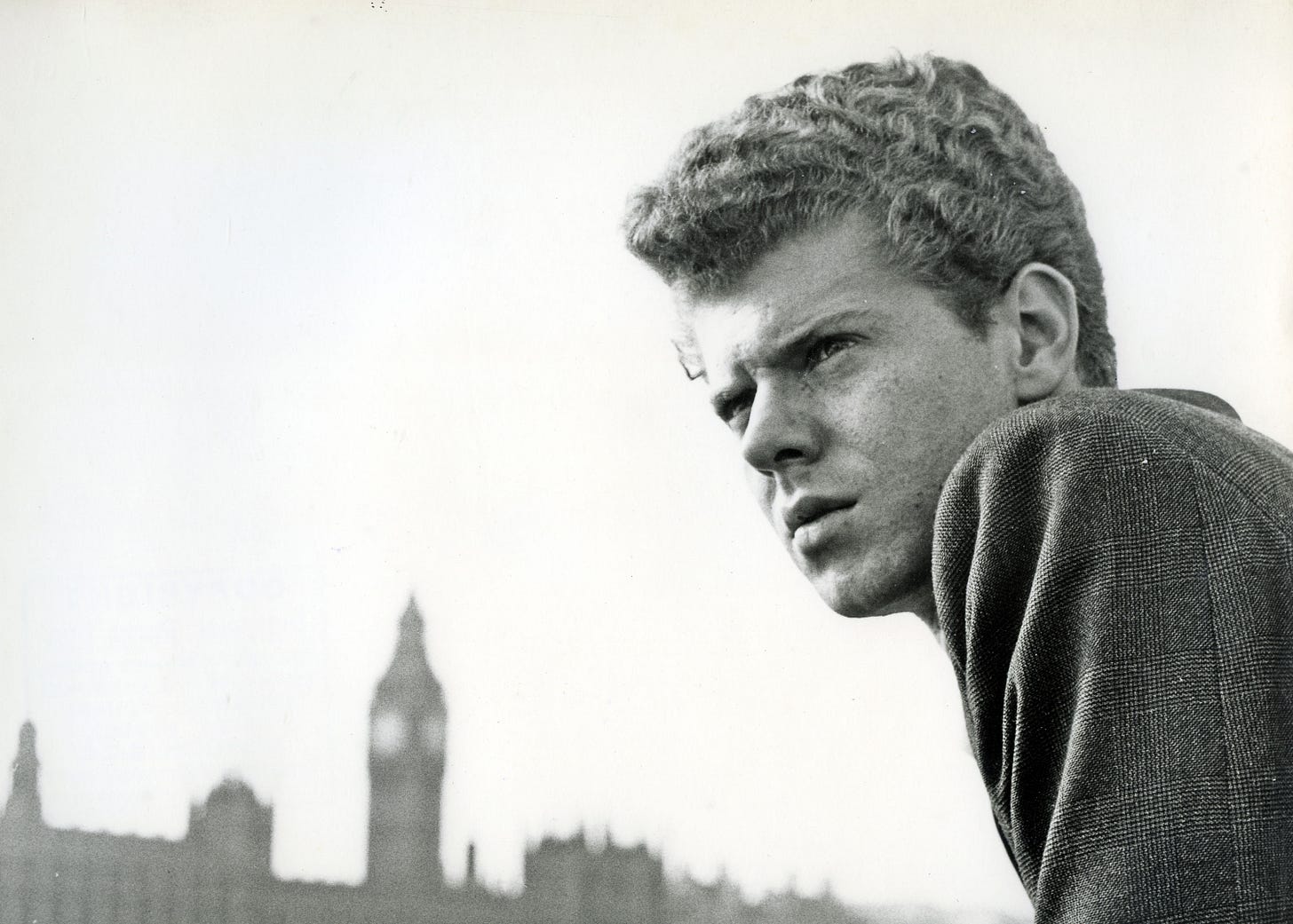

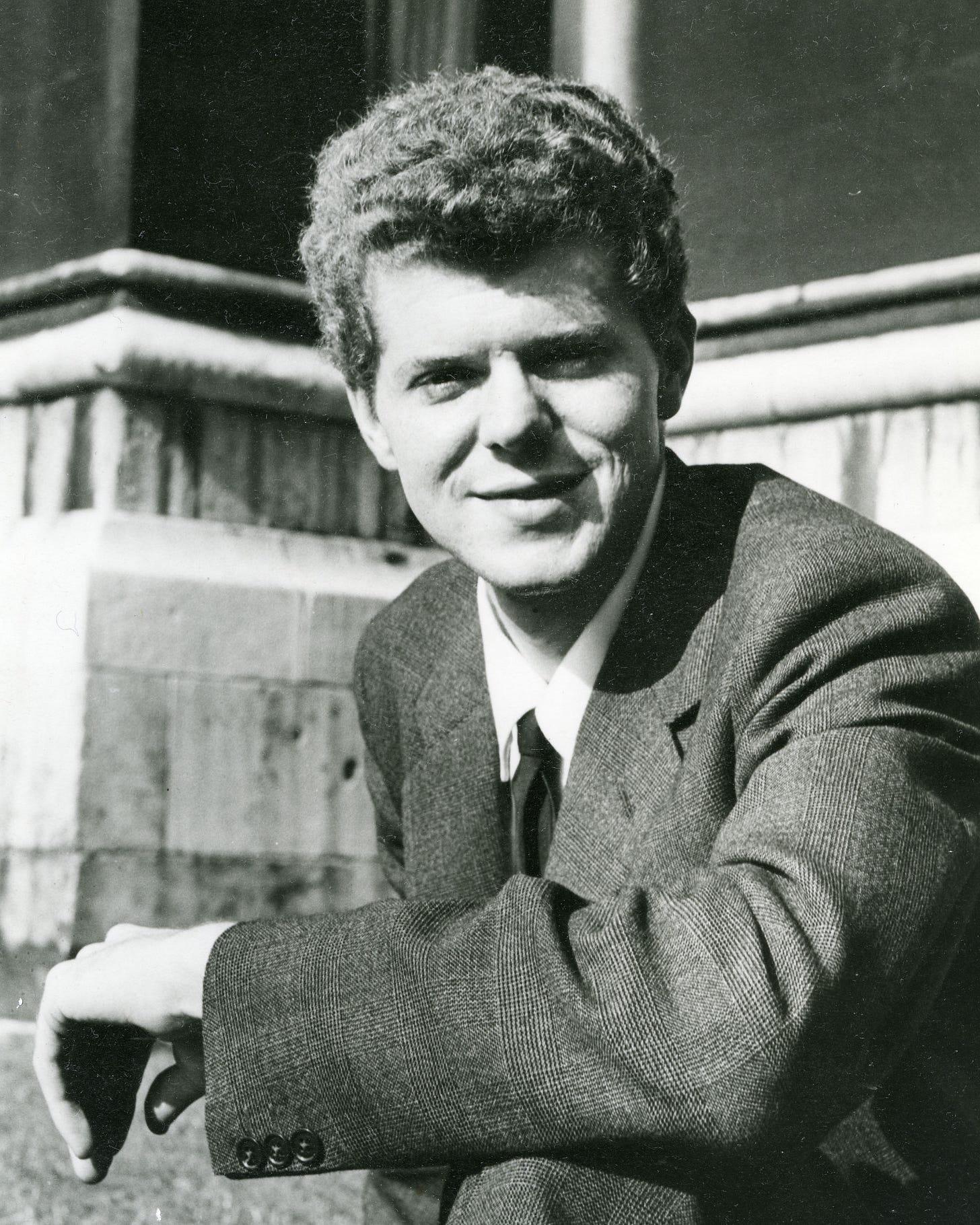

The next demigod was, of all things, a Southern country boy. But when Van Cliburn stunned the (not just musical) world by winning the first International Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958, he might as well have descended from Valhalla into Moscow. He stood 6’4” but seemed even taller, thanks to that long hair that had become de rigueur among romantic virtuosi. His manner was courtly, his voice a honeyed baritone. At the piano he often gazed dreamily upward, as if communing with the angels. Russia fell in love with him. So did America, which welcomed him home with a ticker-tape parade in Manhattan and a Time Magazine cover that heralded “the Texan who conquered Russia.”

Stories about his triumph spun quickly into legend. One, later debunked, was that the esteemed Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter, a juror at the Tchaikovsky, had ignored the 1-to-10 voting scale, awarded 100 to Cliburn and gave every other contestant a mark of 0. Another, more likely true, was that backstage in Moscow, as the American played the slow movement from the Tchaikovsky Concerto, a janitor with no musical erudition or interest stopped sweeping, wrapped his arms around himself and began to weep.

The point is that as with Liszt and Paderewski, the aura of Van Cliburn, the first pianist to sell more than a million copies of an album, dwarfed estimations of his powers as a musician. On blogs.loc.gov (the Library of Congress blogs), Stuart Isacoff cited “his eccentricities, curious social associations and exaggerated persona [which] could veer toward affected grandiosity or oversaturated sentimentality.”

In 1977, I persuaded Keyboard Magazine to send me to Fort Worth to cover the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The quadrennial event launched in 1962, at the peak of Cliburn’s renown. This was my first big-time assignment as a music journalist, so I threw myself into it. For four days and nights I did interviews, tried to document backstage drama, attended an opulent cookout for contestants at some oil millionaire’s house (with an entire dead steer rotating slowly over a barbecue pit) and even got help from Bronze medal winner Jeffrey Swann while trying to deal with a flat tire on my rental car. But the Big Get was, of course, the legend himself, who graciously gave me time for a long chat.

Now I’ll be candid: This isn’t my best interview, for two reasons. First, Cliburn was extremely guarded. My first glimpse of him was as he perched at the corner of his bed, his back erect, his hands folded in his lap, a wan smile on his face. Of course the guy was exhausted, so no doubt he wasn’t at his best. But the other impediment was that I hadn't been classically trained, which meant that I couldn’t zero in on specific issues of interpretation or technical challenges. To compensate I boned up on Cliburn’s previous interviews with, frankly, more knowledgeable inquisitors And I did what I would do many times in decades to come: I guessed at what he was most comfortable talking about (in this case, the competition) and used his comments to chart a path for the interview to follow, with occasional detours when a peripheral topic popped up.

Now, after getting this installment together, I’ve revised my opinion. This was, I think, a pretty decent dialogue. On the subject of competition as a motivation for creativity, we had a good exchange of opinions, though mine were crafted not to express my point of view but to encourage him to dig a little deeper into his thoughts.

Years later Cliburn and I would sit down again for another interview, though as the title and my intro to this project suggest, it proved memorable for another reason. I like to think that my bloodied lip that day with him in San Francisco had nothing to do with any offense I may have committed back in Fort Worth.

****

Since we’re here in Fort Worth at the piano competition that bears your name, I’ll begin by asking what in your opinion makes this one unique?

I feel that the young contestants here have viewed this competition as more of a festival, or a learning and sharing experience than in many other competitions.

How so?

Maybe because our contestants have been quite mature. I’ve talked to some of the contestants that had been excluded from the next round. and even they have a remarkable philosophy about the whole thing. They’re free to have group discussions and talk sessions with various members of the jury. They also will sit around with their peers, discussing what they have learned, what they have found out about themselves, how they thought their playing was and how their lives are going in relation to where they are now. They really are so philosophical! It is very heartening for me to know the depths of character of some of the contestants.

On the other hand, some observers of the classical music world have suggested that competitions have become too important to the process of developing young talent.

Yes, I’ve heard that. But I think it should always be borne in mind that competitions do not signify a life’s career. A competition is only one of several doors to step through. It is up to the individual to take the opportunities that the door represents and to make them count for a higher development of his or her own life.You can use the privilege or abuse the privilege.

Sometimes I’ve heard the term “competition player,” which I assume describes younger musicians who deliberately conform to a judge’s idea of what excellent playing is.

I should think not, because I think it would be very important that the individual element be there. since the judges are awarding to an individual, not to a group.

It’s also been said that competitions only measure a person’s performance at a particular moment, as opposed to what they do over an extended period.

That’s why I say that it’s never a yardstick; it’s merely an opportunity. You wish that you could give the same opportunity to everyone, but then that’s why you would have a jury competent qualifications as you can find that you engage to search on your behalf for a winner. You have to leave it in their hands., and that’s very hard because you realize that you’re not dealing with apples and oranges, but with human beings, human lives and human talents.You wish that not were just apples and oranges; it would be so much easier and you would feel so unemotional about the whole thing. That’s why you’re so anxious that everything be very fair and very right.

“Ultimately, the only person you can compete with in a career is yourself.”

Given the impact that losing in a competition can have on someone, isn’t it possible that these contests could damage a young participant’s development?

But don’t you think that life is a competition? I really think that ultimately the only person you can compete with in a career is yourself.

Yes, but still, isn’t the impact of participating in a music competition unpredictable, if not through one’s life then in the next early years of career development?

Yes, but I think it’s like Rudolf Serkin once said: You can have a career if you’re able to live through the scars, because music development brings many scars — and you remember them all. You have good and bad days, you have lukewarm feelings or you have very intense feelings; there's just such a wide spectrum. I think that one never feels that one completely plays one’s best. I don’t know of anyone who really feels that they have done a totally satisfying performance. In your magazine’s own interview with Alexis Weissenberg, he said that there are so few nights in one’s whole life that one feels completely happy with one’s playing. This is very true.

The other great competition in your life was the Tchaikovsky in 1958, which spectacularly launched your career. What led to your decision to compete?

Well, I heard about the Tchaikovsky first from Alexander Greiner, who was the concert manager at Steinway & Sons. He had gotten his brochure describing the competition, so he wrote me a letter, which I received in Kilgore, Texas, where my family was living. He also called me, saying, “You must do this!” I was immediately taken with the idea of going to Moscow because I had always wanted to see the Church of St. Basil. That had been a lifelong dream of mine since I was six years old, when my parents had given me a child’s picture history book of the world. I remember this so well, as if it were yesterday. There were two pictures in it that had given me just a big, big thrill. The first was the Church of St. Basil. The other was the view of Parliament in London with Big Ben. I wanted so passionately to see them in person, and I asked my parents, “Will you please take me there?” Of course they thought that was some childish little thing, so they said, “Yes, we will see that you get there.”

Did they go with you to Moscow in 1958?

No, I went alone. I went first to Prague. Then I went to Moscow on their TU-104 jet service. At that time we did not have jets in the United States for commercial purposes, so that was very exciting. We arrived late at night, towards ten in the evening. There was snow piled up all over the ground. It was very romantic. It was everything I had ever dreamed about. This very lovely lady from the Ministry of Culture met me; she was very sweet, very charming. I said, “Do you think it would be at all possible as we go to where I will stay, past the Church of St. Basil?” She said, “Of course [laughs]! So we went by there, and I thought my heart would stop. I just felt that my whole trip to Moscow was complete. It was so thrilling!

As thrilling as playing in the competition itself?

Well, it was an exciting thought just to play in the preliminaries in the Moscow Conservatory, in this hall where so many of the fabulous names in music had performed. Just to be in that hall was quite a thrill, an awesome thing.

Did you expect a reception as wild as the one you received on returning to the States?

Oh, no! Never did I dream it would happen.

Looking back, do you think that the pressures of your early fame in any way hampered your development as an artist?

Well, this is something we’ll never know. We often think back on life and see that certain opportunities were just so valuable, that certain things outweighed other things. In a sense I was very fortunate in that period because of everything that had happened, which allowed me to study for a few years with [conductor] Bruno Walter, for example. This was during the last few years of his life. In fact, I played the Brahms Concerto In B-Flat at the last concert he ever conducted; that was in Los Angeles, on December 4, 1960. Also, because of the very nice things that happened to me, I was able to have a wonderful association with [conductor] Fritz Reiner. I shall always be grateful for that. That was such a wonderful and inspiring period! These things were so thrilling. You can only wonder if it all would have happened in the same way had certain events been different, so you have to sort of weigh one against the other.

The Prairie Pianist

Your background, being raised in Texas, was quite unusual among classical artists at that time. Did that have any effect on your creative and personal growth?

Yes, I think it did. It was less densely populated than other areas, but it had a creative flow and a creative biorhythm that was very conducive to the musical talent of a young person like my mother when she was growing up. So I think, in a sense, that this has given me a great deal of respect for the less populated areas, because they have a great deal of space for the spirit to breathe in. I think also that trees and the earth and all of those things are extremely important to anybody’s development.

Did you listen to the indigenous music of that area?

Yes, to some extent. But my childhood was really rather quite classically oriented. My mother came from a very nice family that had a great deal of awareness of the arts. My grandfather was in the Texas legislature, and my grandmother was a violinist. They were socially prominent around Texas. They were always aware: They read a lot and they knew what was going on. They sent my mother to study at the Cincinnati Conservatory right after she graduated from high school. Then from the Conservatory she immediately went to New York to study with the great Liszt pupil Arthur Friedheim.

Was your mother your primary musical model?

Yes, but not my only model. We had recordings of Rachmaninoff, an old recording by Mr. Friedheim and records of many other pianists of that era. Also, between Shreveport, Dallas, Fort Worth and Kilgore, where we moved to from Shreveport, there were always wonderful concerts. As a matter of fact, when I was a very small child, Rachmaninoff played one of his last concerts in Shreveport. As you can imagine, there was a city-wide celebration that we were able to have Rachmaninoff come to town. My mother was part of the committee that brought him in.

Were you old enough to attend his concert?

No, I was very small. And yet, I knew consciously who this great man was. If my history is right, Rachmaninoff’s last date on this very last tour, if he had the strength to get off the train, was in Wichita Falls, Texas. It was from Wichita Falls that he went to Beverly Hills, California, to spend his remaining three or four months.

When you began your studies at Juilliard, Rosina Lhévinne was your piano instructor. How did her approach to teaching differ from your mother’s?

Their methods complemented each other. I still have letters from Mrs. Lhévinne in which she wrote extremely complimentary things about my mother, so much so that a couple of other students that my mother had that Mrs. Lhévinne took them without audition. That always pleased me. But the nice part about my mother’s teaching was the respect that she received from me, and justly so, because there was nothing she asked me to do at the keyboard that she could not demonstrate. For a young child or one going into the teenage period, which sometimes has its difficulties, that is a great plus in a relationship with a teacher. It is important to hold that steadfast respect for your teacher. Also, my mother had a very good psychological approach in that, when it came time for the piano lessons, she created the atmosphere that she was not my mother. That is a very difficult thing for a parent to do, but she was always able to draw that line of demarcation so that she was briefly not my parent, but my teacher.

Did you ever think about being a teacher yourself?

No, not really. Only to the extent that I might offer thoughts or something like that. It’s a grave responsibility to be the right kind of a guide with a student because you’re nurturing a talent and helping to propel or inspire it to go on and find its own place. The responsibility toward the student lies in the fact that you must be sure that you’re always telling them the right thing.

Also, I imagine it would be a challenge to combine two careers, as a teacher and a performer.

I think that’s true, because my time and activity and mental priorities would always be divided.

Still, are you interested in expanding your activities — getting into conducting, perhaps?

I did conduct for about three years. It was a pleasure, but eventually I ceased conducting.

So your main focus will remain on the piano.

Yes. I enjoy it better.

You have been criticized for not including many works beyond the Romantic era in your repertoire. Have you in fact explored more contemporary pieces?

I have made explorations into it, yes. I’m trying to find something there that I can feel personal about. I suppose the most contemporary work I’ve done is Barber’s Sonata in E-Flat Minor.

“You are not playing for yourself. You are there in a service capacity.”

How do you prepare your own interpretation of a Romantic masterpiece?

There are several things you have to take into consideration. First, you have to follow a great composer’s markings. You have to remember that pianos today are superior to what they had then. Then you have to keep in mind, when you are performing the piece, that you’re not playing for yourself. That’s the first cardinal rule of performance. You are not playing for yourself. You are there in a service capacity, so fifty percent of you must be involved with the music and fifty percent of you must be out in the audience. It’s like being a good conductor. A conductor must, of course, be very involved in the music. But he must be listening to the whole sound and gauging the total effect of the orchestra from an organizational standpoint, so that he is ever aware of what the person in the farthest point in the hall is receiving, while coordinating it for the person in the nearest seat as well. You have to gear things somewhat differently than you would in a small drawing room. The halls, many of them, are larger and often they have less wood in them than the drawing rooms of the nineteenth century. Today you have concert halls that will seat sometimes over three thousand. But no matter where you’re playing, you try to give as many people the right effect of the composition as you can.

Can you compare preparing for a concert appearance versus a recording session?

Well, going in to record in the studio is always a different experience than playing live. You just cannot deny that. Yet when you’re in the studio, you have to imagine that the microphone is the audience and bear in mind that there are ultimately going to be people listening. But there really is an electricity which you cannot ignore in live performances.

Risk & Spontaneity

Is the popularity of live classical music declining?

No. I know that there have been some people who have said, “Well, we have recordings and they’re wonderful, so we really will ultimately abandon the concert hall.” I don’t feel that way at all. I feel that live music-making is so exciting and so thrilling that, no matter how often you may have heard a composition, when you go into the hall it is a very fresh and new experience. I think that people sometimes are so geared to recordings, which are generally as nearly perfect as possible, that the matter of perfection in the concert hall is over-magnified to the degree that it becomes plastic and it’s not what you want anymore. You want that spontaneity; you want that risk element.

So it would be a healthy trend to put more live classical recordings on the market?

Yes!

…

What considerations do you take in planning your concert program?

Well, if you look at the programs of most of those performers who are generating a career, don’t you think that they usually play the pieces they want to play? This is very important. You should not think about anything but yourself, what you want to play and what you think the audience will enjoy hearing you play.

As you approach your twentieth year on the summit of your profession, how would you describe your relationship with your art?

I’ve always thought that, if you’re going to take the time to learn something, you’ll want to have it always. Great music, for me, is like a great painting that you take into your home. It’s never going to be for sale and you cannot give it away, because it becomes immediately both priceless and worthless. It has no external value because it’s in you, in your inner home. The beauty of classical music is that if you’re working with a really wonderful piece of music, it is always in vogue. If it is classic, it is forever. There is no fad to it, so that you’ll always want to have it with you.

####

Thank you so much for this one, Robert!

I’ve been enjoying your stuff for years (and admiring your range and sense of the genuine, also – rare stuff) – on top of that, I remain super-jealous of your column title – stupendous on so many levels (looking forward to the other Van Cliburn story – though the unspecified nature is narratively fun)

I moved away from home when I was still a kid, and used to salvage hi-fi gear from the neighbourhood garbage (the 70s was a great time for this) – no accident I later became an audio technician, no doubt. The funny thing was, while all my friends were saving up for rock and pop albums, I remained obsessed by classical and jazz (pretty much still there – though very open).

Van Cliburn was on my clanky old record-changer all the time (along with Brubeck, Mahler and Ella Fitzgerald). For my birthday that lonely year, my roommate – who worked at the legendary Sam the record Man, in it’s truly glorious prime, bought me a copy of Horowitz playing the Waldenstien and Appasionata sonatas (a record I will keep forever, even though it’s been awhile since I could be bothered to get a turntable working).

Of course I later got into the heroic-obsessive Glenn Gould (and used to eat at his favourite booth in his favourite restaurant, all the time, since I lived in the area). Miss those days when performance and courageous interpretation was itself recognized as great art. I later married the daughter of a superb and lifelong working jazz guitarist sideman, Neville Barnes (think Charlie Christian played by Ed Bickert) and in my career as a tech, watched the entire industry undergo several severe dislocations. Heartbreaking stuff on the level of so many inspiring dedicated individuals – big-culture level, too.

After technicians were rendered obsolete, I found myself work as an art model for painting students, and in that masterclass of deep-patience, observation and self-control, I finally realized the magic ingredient, common to pretty much all of the artistic projects I’ve found deeply bewitching.

Refined intention. Which is a theme which comes up so often in your work (and in so many different forms and from so many different angles) that I find every piece you share with us a delicious draught – thank you!

(Jarret and Joel, both really memorable stand-outs)

Cheers man – keep reminding the world that music is magic!