Back around 1997 or so, I finagled tickets to see Béla Fleck & the Flecktones at some venue in Manhattan. I can’t remember where it was, but I will not forget the impression they made on me. All I knew about these guys was that Fleck was playing banjo at a level way beyond what any of his peers could even imagine. What I learned was that the entire lineup performed with similarly unimaginable excellence on their instruments.

The last time I’d felt that overwhelmed was about ten years before, when I saw Weather Report at the Warfield in San Francisco. Jaco Pastorius in particular stunned me. His technique, his ability to play intricate melodic improvisations on bass guitar, even his wiseguy street-kid attitude, persuaded me that I would never hear anyone who could approach, let alone surpass, his virtuosity.

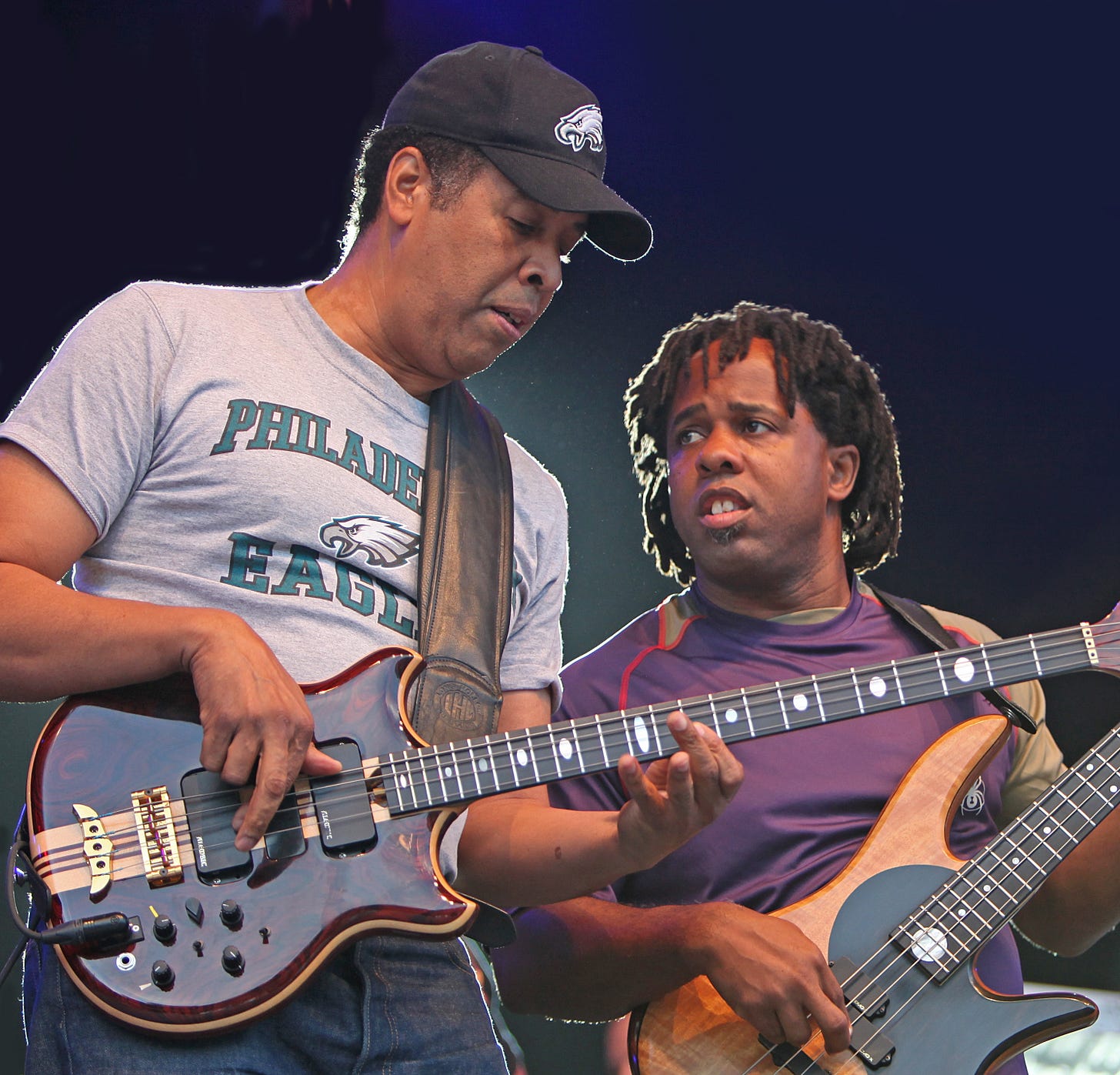

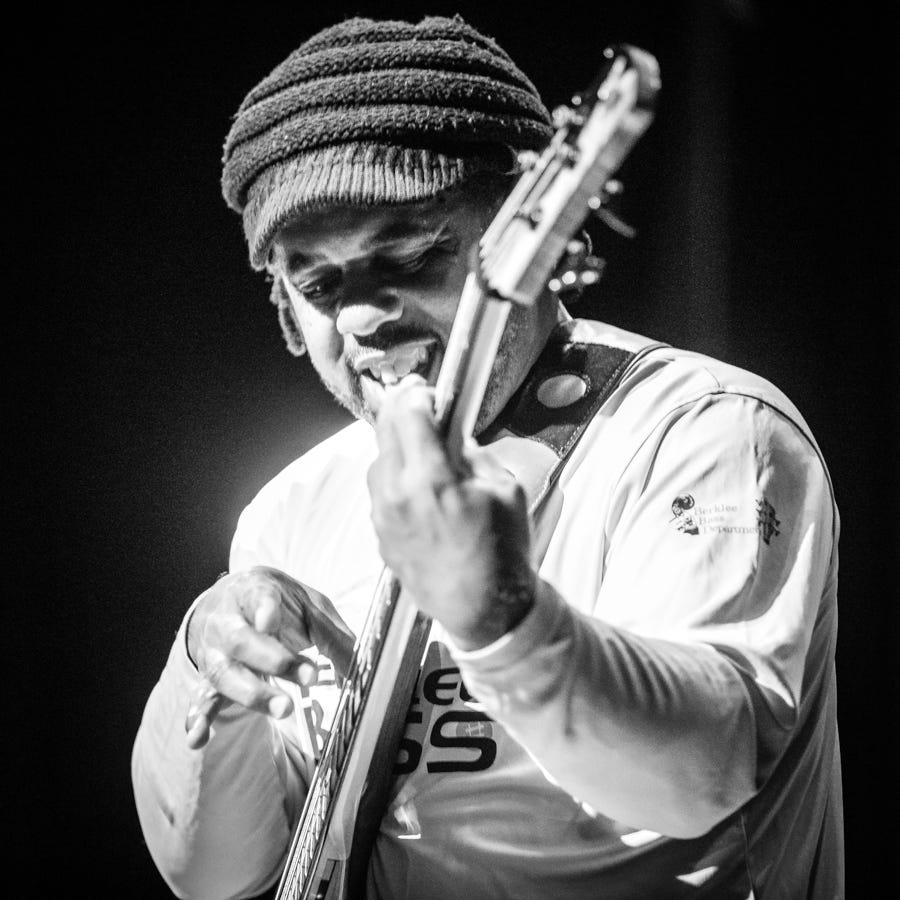

That was my opinion all the way up to that Flecktones concert, when their bass player Victor Wooten stepped into the spotlight. His style differed from Jaco’s, with the emphasis on churning, string-popping explosions of rhythm, laced deftly with fleet, sleek single lines. It was, I would say, a transformational exhibition.

A few days later, I was in my office in the Viacom Building, overlooking Times Square, determined to spread the news about Wooten. As editor of Musician magazine, I wanted to go beyond that and analyze his chops and his revolutionary reconception of the bass guitar and its role. After a second or two of thought, I decided to assign the story to Chip Stern. To my surprise, he declined. I asked why and he said, “I play some drums, but I’m not a trained musician. I can’t technically dissect what any musician does.” But I insisted. Something told me he’d hit a home run with this one.

He did. Chip was a difficult guy. Not easy to get along with. He was, though, an exceptional writer – from what I can see, he still is. The proof is online, but for me his Wooten story was a masterpiece. If you can find the May 1997 issue of Musician, check it out; despite his professed shortage of know-how, he captures the essence of who Wooten is, why he’s a pivotal figure and how his thought translates into what he delivers on his instrument.

Anyway, twenty years later, I got the call to write Wooten’s PR bio for his upcoming album, Tryptonyx. We met one afternoon on the deck of the Frothy Monkey coffeehouse, across from Belmont University. Throughout our conversation we were politely but frequently interrupted by passersby, who couldn’t resist shaking his hand or just saying “thank you, Victor, for the music.” Victor paused, smiled, thanked them in return. He was and is a local hero in Nashville, an icon among bass players around the world. Just as important, he’s a good guy.

As Fleck said while introducing him that night in New York, “I’m just glad he’s on our team.” Me too.

****

You were raised in a military family that moved around a lot. Where did you grow up?

Well, I’m the youngest. I don’t think any of my brothers went overseas. I was actually born in Idaho, right outside of Boise. I don’t know for sure where we moved directly after that. I think we lived there for less than a year. We may have had a small stint in North Carolina. But I do remember Hawaii. That’s where we started playing music together.

How old were you at the time?

I didn’t even go to school in Hawaii. I was really young, right around two. They gave me a toy guitar and I would play along with my brothers. There are home movies of us playing in the front yard with the neighborhood kids dancing around. I remember some of that. I remember the house in Hawaii.

What did you see when you looked out your window there?

We had a coconut tree in the front yard and a banana tree in the backyard. Once or a few times a year a guy would come and barefoot-climb the coconut tree with a big machete and chop down the coconuts. You had to stand out of the way ‘cause he’d just let ‘em drop. The houses were up on stilts; we could crawl under the house and play.

Were you parents musical?

Yes, but they didn’t play any instruments. They would take us to concerts. I remember seeing James Brown in 1970 and ’71, I think it was. I would have been in kindergarten and first grade. Around that same time, we were opening a lot of shows in California. When I turned seven in Virginia we were opening for a lot of big bands like War.

My parents grew up Primitive Baptists, old Southern Baptists. Instruments weren’t even allowed in their churches. But my dad was a big country music fan. The only radio station they could get on the weekends was the Grand Ole Opry. He liked to sing a lot of that old country stuff. My mom would play a lot of her gospel records on weekends and Sundays. They supported whatever we chose to do as long as we were good people. That was their main concern.

In which branch of the service did your dad serve?

He was in the Army. He fought on the ground in the Korean War. When they invented the Air Force he switched over to there. He spent a lot of time in the Air Force working on naval ships, so he used to joke that he was in all three branches. When he passed away, my mom made sure he had a 21-gun salute and a military funeral.

Did your dad share some of his experiences in the war with his sons?

A little bit, maybe more with my older brothers. I got to hear just a few stories. I can’t remember any good ones, but they were about not only having to deal with the horrors of war on the ground but also racism at that time. I heard stories about how their platoon would do a really good job, but the guy giving out the medals would walk right by the black people and give it to the white guy standing next to him. That’s what they had to deal with.

My dad was stationed with my mom’s brother. He started writing to my mom as a pen pal. They were engaged before they ever met.

You mentioned James Brown and the horrors of war. Both of these are noted thematically on your new album.

Absolutely, because it doesn’t seem that the story changes much. In the future and the past, it seems like we’re telling slightly different versions of the same stories, fighting slightly different versions of the same fight and maybe learning slightly different versions of the same lessons. So what James Brown sang about, what Marvin Gaye sang about, Curtis Mayfield — those songs are still relevant. Someone needs to keep singing them.

Do you sing?

My brothers are better singers than I am, but I still sing. I enjoy it; I just don’t like what I hear [laughs].

But even though you were raised in an a cappella church, you all wound up playing instruments.

Well, Reggie, Roy and Rudy, my three oldest brothers, they’re all only a year apart from each other. Only two years separate the three of them. I heard that they saw a band one day and got excited. I think there were a couple of hours in the day between my mom’s school and work, or maybe between their two jobs, where my brothers would have home by themselves. They were young; I wasn’t even born yet. Reggie, my oldest brother, is only eight years older than me. But our mom knew how to raise kids. She would tell us, “When I’m gone, Reggie is in charge. So you don’t have to like what he tells you, but you have to do it. If he’s wrong, I’ll deal with him, not you.”

So they would stay home by themselves. Apparently they saw a band, went home and started a band. They called Mom and said, “Mom, we got a band.” Mom, ever the supporter and encourager, said, “Okay, then practice. Because when I get home, I want to hear it.” That’s what they did: They practiced and when she got home, they played for her. I think one of my brothers was shaking a chain. Another one might have been blowing through a straw. I’m sure my mom just praised them, told them how they were, because they never stopped.

Three years after Rudy, Joseph was born. He was the next band member, on keyboards. I came three years after Joseph — and they had a bass player.

Why are certain families like gardens of talent?

Every little sibling looks up to their older brother or sister. You gravitate toward doing what they do. We all learn to speak English because everyone in the family speaks English. If you live on a farm, everybody’s going to know how to farm. It doesn’t mean you’re gonna grow up to be a farmer but you’re gonna know how to do it. And again, not all families do it. It’s the rare family where they all play music professionally. The ones that do, stick out: the Marsalis family, the Jacksons.

So I was just copying my brothers. It allowed me as a youngster to belong, to be able to do things with my older brothers. Every little kid likes that.

Was there any element of competition between you and your brothers?

No, not that I can remember. I’ve heard my brother Joseph talk about competition in the sense of, “Wow, he’s getting really good on his instrument! I need to practice and make sure I get good on mine!” But it was always supportive.

You were all on the same team. You wanted to get better so the team would get better.

Absolutely, that’s the way it was. In my beginnings, Reggie taught me everything. I get a lot of the credit but if I’m two and he’s teaching me to play bass, he’s only ten. By the time I’m five or six, we’re opening for Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly tour on the West Coast. But Reggie’s the one who got Joseph and me ready for that. That’s the real story.

So you never took lessons from anyone outside the family?

We learned from everyone. I started playing cello in the orchestra in sixth grade in Virginia. I learned how to bow. I learned how to read music. That was sort of like lessons, but in sixth grade I’d been playing bass nine years already. So I knew music really well; I just didn’t know how to read it.

What instrument were you playing at age three?

When we were playing in that front yard in Hawaii, I was playing a little plastic Mickey Mouse guitar. You could wind it up and it would play back a tune. My brothers figured out the right way to do it. A lot of times now, we teach you the instrument first: Here’s how you hold it. Put your fingers here. Communicating is the key. With my brothers it was about playing music, even if it’s on a toy.

So I strummed this toy guitar and bounced on my seat. I look back on it now and I realize that it’s the same way a baby learns a language. They taught me to play first, the same way a baby learns to talk: You learn the actual words and theory later. It’s about communicating. Babies are born communicating and we accept it. We learn their method. We teach them our method later. Like, you learn the difference between a statement and a question, even though they can be the exact same words. You know what it means when your mother raises the pitch of her voice. Or maybe your dad lowers the pitch of his. You understand these things before you learn words.

I was learning music that way. Before I knew where to place my finger on an instrument, I knew rhythm. If my brother did a certain type of fill on the drums or on the guitar, I knew what it meant if the hi-hat is open at the end of a four-bar phrase. So by the time I was actually learning to play the instrument, I was learning songs I already knew, the same way a baby’s first words are things they already know: more, milk, Mom. My brothers knew how to do it in that order: Just give him an instrument and let him play with us, the same way a baby gets to jam by talking with somebody else. That was a gift.

What did it mean to you as a kid to open for musical legends?

My brothers remember more of that than I do, but Curtis’s team loved us. They were actually going to “discover” the Wooten Brothers. They took us into the studio. They had musicians, they had songs for us. There was this new celeste song on a keyboard they wanted to get out on our record first before anyone else used it. But that whole thing got cancelled.

Why?

I found out much later, when I was almost an adult, that it was because they were told there was another group of five brothers living in California and there wasn’t room for two groups of five brothers.

I wonder who they were?

Exactly. But I do remember a Curtis Mayfield show. There were supposed to be two shows that night. Curtis did one show, took the money and split with his manager. There was a full house waiting to get in for the second show. We’re in the dressing room. I’m sleeping on my mom’s lap. And it’s tense down there. Everyone in the dressing room knows there’s not gonna be a second show. Someone’s got to deal with this sold-out crowd outside. I remember this only because my brothers have talked about this all my years. But a guy came over to us and said, “You boys need to get out of show business while you’re young [laughs].” That was the advice we got.

As your family band improved, did you start listening to records differently? Did you start focusing more on bass parts?

Absolutely. Right around age nine, when I was in fourth grade, the fusion scene was starting to hit. We were getting Stanley Clarke from Return to Forever. We’re getting Mahavishnu Orchestra with John McLaughlin and those guys. Right around this time Reggie stops teaching me my parts, so I’m having to listen to the record to learn my parts to these songs. I’m starting to really pay attention to who these people are. I realize that there’s a guy named Bootsy Collins. There’s a guy named Larry Graham with Sly Stone. I’m starting to pay attention to who these guys are.

You were listening to the innovators. Did you also listen to traditionalists, the Ray Browns?

I did, but I didn’t really pay attention to their names until I’m nine or ten years old. I start realizing that Ray Brown was on the Merv Griffin Show for a while. My brothers would say, “You’ve got to watch this bass player!” My mom’s sister turned me on to Willie Weeks’s bass solo on “Everything Is Everything” on Donny Hathaway Live. That was the first bass solo I remember ever learning. We learned our parts by listening either to the album or the cassette, having to rewind it. It was around that time that I started paying attention to names. But I wasn’t going back and saying, “Oh, that was James Jamerson” or “That was Bob Babbitt or Carol Kaye.” I was going, “Oh, this is Stanley Clarke.”

“I learned to speak music the same way you learn to speak English.”

What you didn’t have was an instructor who tried to push you into a traditional bass role. You started in the future.

I learned to speak music the same way you learn to speak English. No one sat you down and said, “Here’s the role of your voice. Here are the words you need to learn. Go and practice.” No, we just talked. You were allowed to speak incorrectly; no one ever corrected me. You did that for years before you learned any theory. I learned music the exact same way.

When you played cover tunes, was it all about duplicating the bass parts or creating your own interpretation of them?

It was both. We had freedom. If we were playing at a wedding or an NCO club and they wanted to hear certain songs, we made sure those songs were recognizable. But we always had the freedom to change it up. We might take solos. My brothers understood that if people are dancing, the song doesn’t end. You keep going. And when we get tired of this song, what other song has the same tempo? Let’s morph into the next one. To play that same song the exact same way the whole time could be boring.

As you started evolving your unique approach on bass, did older musicians sometimes act puzzled?

Yeah, but not until I was quite a bit older. When you’re younger, people love whatever you’re playing. I don’t remember hearing anything crazy or negative from anybody. But as I started getting older and reading Bass Player Magazine and hearing Anthony Jackson, who’s now a good friend of mine, say, “No, you don’t slap on the bass. You don’t even wear a strap. A six-string bass is a contrabass.” Or Jeff Berlin would say, “Don’t use a metronome.” I’d hear a lot of things going against what I was doing. But that never took a hold on me because of my brothers. I had my own gang, my own posse at home, including my parents, and they overshadowed anything that anyone outside said.

Music in the Seventies was not a viable career choice. It was a hobby. You needed a real job, something to fall back on. But my parents supported it. My brothers knew what they were going to do. So by the time I got to high school, I had much less of what they had to go through. A lot of people questioned what I was doing because I was doing some different things on the bass. But a lot of times my brothers were the ones who pointed me toward them. Reggie would say, “Man, if you did this with your thumb …”

Obviously you have fantastic technique. What drove you to keep building and building on your chops?

It was to be able to produce what I was hearing in my mind. It’s the same thing that possesses you to learn more words. There’s more you want to say.

So you were hearing, for example, 64th-notes in your bass lines …

Oh, yeah! I wasn’t really hearing them on the bass, though. I was hearing it on the drums.

“I was learning drum licks and drum solos on the bass.”

Every little boy who gets into music wants to play drums first. You want to hit things. But we had a drummer already. But I was still fascinated with drums, so I was learning drum licks and drum solos on the bass. But there was no technique that would allow me to do it. When I learned what we now call slapping — we called it thumping because that’s what Larry Graham called it — that gave me the power but not the speed to play a Billy Cobham roll. Then Reggie showed me one thing with my thumb, which was to use it up and down like he uses his guitar pick, that opened a portal in my brain. Then when you add plucks and multiple plucks and left-hand hammers, all of a sudden you’ve got ten fingers, man.

I saw my brothers’ instruments on my instrument. I approach my instrument the same way they approached theirs. Stanley Jordan really got me good at tapping. But I was exploring it before I knew who he was because my brother was tapping on keyboards. That’s all it is. You take a saxophone, which is vertical, and lay it on its side. What does it look like? It’s a guitar! I could see that. So I could learn from whatever my brothers were doing. I could take drum rudiments and apply them to the bass. Reggie played chords on the guitar; the bass is just a four-string guitar. So why not play chords? My brother Joseph plays with ten fingers on the piano. If I give him my bass and he lays it in his lap, immediately he’s good. Why can’t I be good? So I was dabbling with these new ideas on my instrument, not trying to be different but because I was living with four great musicians. I heard them do it and I wanted to do it too.

As you evolved, you’ve developed a different kind of role for the voice. Rather than just lay the foundation, you play as one of several voices in the band.

Yeah, but the good thing was that I learned to support the low end first, so that even when I venture away from it the foundation is still there. That’s my goal, to never abandon that. Yeah, I can go up high and play a melody. At the same time, when we studied James Jameson, he wasn’t a normal bass player. He wasn’t like Bootsy and James Brown, playing the same part over and over. He ventured through the chords in a way that not many bass players did at that time. What I learned from James was to not have to stick to one part. You can venture through the chords but James Jamerson still made it feel like a bass part. A lot of bass players will go up through the chords and it sounds like they’re soloing. James Jamerson made it still feel like a bass line. Listen to “Reach Out” or “What’s Going On”: He’s outlining the chords perfectly and it still feels like the bass part. There’s a way to learn that. Fortunately I learned that very, very young.

At the same time, my brothers were giving me solo spots during the show, where I would do theatrical things — play behind my head. I was little enough that I could get up on one knee, stand the bass up and play it like an upright. They would guide me, like, “Hey, man, try this!” So we also understood the art of performing as kids.

You learned your values from your parents. Was it difficult to stay with them as you moved through the music business?

You know, I don’t remember much of it being a challenge because I’ve never not done it. I’ve never not played shows on the weekends. When I was five or six years old, I’d come home from school, take a nap, do my homework and go play the gig. I don’t know anything else.

Also, I had my parents and my four older brothers to help with everything. It was right around when my three older brothers went to college: I think Reggie went two years and the other two went one; my brother Rudy, the third-born, graduated a year early and went to college the same time as Roy. So Roy and Rudy joined Reggie the second year of college. That was when, with their parents’ blessings, they dropped out.

I was in sixth, seventh, eighth or ninth grade, that it dawned on me: I can just keep playing music. I don’t have to, for lack of a better phrase, get a real job. I can remember that in second or third grade, like any other boy in the early Seventies, I was gonna be a policeman or a fireman. I was playing gigs on the weekend but I didn’t think I was going to go out and be a musician. So when I found out I could keep doing this, in my head it got easier. I didn’t have to take all these tests and apply to college.

Now, don’t get me wrong. There were hardships. Starting when I was five or six and we were doing Curtis Mayfield, that was the first letdown I can remember. We were like, “We’re gonna make it … No, we’re not!” That happened so many times. Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert …

Did you play that show?

No, but he sent people out to the house. They were going to discover us. But that fell through. Stephanie Mills fell through. So there were hard times. But that’s probably true of anybody’s career. I don’t know if it had anything to do with music.

At the present, music keeps me away from my family, my kids and my wife, more than I want to be. I still have to tour to really pay the bills. I’ve got Kaila, nineteen; she’s in her second year at NYU. Adam is a drummer and gymnast; he’s sixteen. Arianna is thirteen. Cameron is twelve.

Parenting As Art

As a husband and father, what do you draw on that you learned from your parents?

Having a child made me look back on all the things my parents did for us. There’s no real manual on how to raise a child. And my parents were alive when my first three were born. I talked with them a lot. I had a lot to draw from. My mom was a talker and a spanker. We’d get spankings. But the talking-to was worse than the spanking. That stuck with you. Even today Mom makes me mentally go through the actions I want to carry out and think about what would happen if I did.

One of the main things I learned from them is to help my kids become good thinkers, to be able to think for themselves. I’m always asking them questions and even answering questions with questions instead of just giving them the answer: “Well, what do you think?” Just to see where their head is at, so they realize that they can make decisions. Sometimes they want to push against you and you have to make sure you’re still in charge. I’m still the daddy.

My parents were really good about letting us see the value in ourselves. Even at a very young age, we knew who we were. We valued who we were and loved who we were. But we also knew that we were no better than anyone else.

What about the broader world of young people in general? At this point in my life, I can see now that music is my way of helping people. I use music to teach life lessons.

“Music is a great way – and a safe way – to teach just about any life principle.”

That’s your message on the last track of the album too.

Yes. Music is a great way — and a safe way — to teach just about any life principle. To be in a band, you have to listen to each other. Bands are the best when every instrument is different, not the same. The differences are valued and supported. Of course, everyone has a role. Everyone knows their role. Everyone takes turns talking about whatever we’re talking about. Through music I can address qualities or parts of life that would be touchy, like religion or politics or racism. A lot of times people might say, “What should I play?” I say, “Listen to the music. The music will tell you exactly what it needs.

I suppose music can be used for ill purposes too?

Yeah and that happens. It’s a tool like anything else. As musicians, we are in a special place: People listen to us.

Lessons from Nature

How did you get the idea of the Nature Camp?

Around 1990 or so, my older brother Reggie turned me on to a book that our uncle turned him on to. It’s called The Tracker, by a man named Tom Brown Jr., a naturalist in New Jersey. Apparently Tom’s story is that when he was seven he met this 83-year-old Indian, an Apache medicine man, who was a relative of a friend of his. This man took him under his wing and started teaching him about the natural world, like how to understand the birds’ language, knowing the plants, seeing tracks on the ground, reading the wind. My uncle told Reggie about this book, and Reggie thought, “Man, Victor would love this kind of thing, like Sherlock Holmes or whatever.”

So I went and found the book. I got about three chapters in when I said, “Man, if this Tom is a real guy, I’m gonna find him and learn from him.” I did some research — this was before Facebook — to find his number. I didn’t realize that it was at the end of the book [laughs]. I signed up for his school in the pine barrens of New Jersey.

From about 1991 to 2001 I kept going to classes and learning. But in my first class I heard him talk about awareness and wide-angle vision and what they call the sacred silence, which is a form of meditation. I’m sitting there saying to myself, “This guy is talking about music! He doesn’t call it that, but he’s teaching music!” Even when he was drawing tracks on the ground, seeing how tracks move, if I put little stems on the tracks they’d be little music notes, it’d be the same thing!” Even more than that, I was thinking, “This is the way music should be taught!” See, musicians are taught to sit in a room and practice. But you don’t become natural in a room by yourself. Think about learning English that way.

So I told myself back then that I would love to get good enough at this to be able to teach it. It wasn’t until it happen that I remembered a little pact I made with myself to be good enough by the year 2000 to be able to start teaching this nature stuff.

So you went out in nature on your own?

Yeah, but not for long periods because I still had gigs. I’ve never been out for a month in total survival mode. Friends of mine have. Most of my experience has been in a classroom setting.

“Music should be about something. Music shouldn’t be about music. If all you do is music, what else is your music about?”

But when you did go out for a while, did that change you musically at all?

Totally. Absolutely. Music should be about something. Music shouldn’t be about music. If all you do is music, what else is your music about? You’ve got to have life. You’ve got to have experiences. You’ve got to fall in and out of love. You’ve got to get your car stolen. Then you have something to talk about. That’s why we can resonate with soul music and spirituals and blues and even country music. Getting away from the instrument, getting into myself and realizing that this bird gets up and sings just because the sun is up, not to get paid … To survive in nature, you have to listen, not only with your ears but with your feet, the sun on your skin, your whole body.

That’s why he talks in his book about listening with your whole body. The sun warms your skin. The vibration of the ground, the wind … You’re listening with everything. You go outside to go inside. When you spend a lot of time outside, you go more inside yourself. That’s the way animals live.

Is your book (The Music Lesson: A Spiritual Search for Growth through Music) a novel?

I call it a novel but there’s a lot of autobiography in there. I call it fiction so that nobody has to waste time trying to figure out what’s real and what’s not. It’s like Star Wars: You don’t have to believe that Yoda is real. But listen to what he’s saying. I took a lot of real stories and put them into a fictional context.

So sharing your experiences through the camp and your book as well as through music is part of your job. It’s your work.

As Béla Fleck and the Flecktones started becoming popular, that meant I started becoming popular in the bass world. I started being asked to teach. But I’d never taught anything. So I started researching teaching. What do teachers teach? I realized that everybody’s teaching good stuff but they’re leaving out the real good stuff. They teach you how to play notes and play scales, which are notes, and chords, which are notes, and key signatures, which are notes. What they call music theory is basically notes. But there’s other stuff. There’s space, knowing when and how not to play. There’s the power of dynamics, how you can get loud by talking soft, Curtis Mayfield soft. No one teaches that stuff.

I heard you improvised the commencement speech you gave last year at the University of Vermont.

That came about through a natural connection. Someone who works at that college as part of the environment field asked me to do it. So I actually wrote a speech, for the first time ever. I just made myself some notes, like, “Mom’s quote.” I already knew I was going to play the whole time. I ad libbed off of a song called “The Lesson,” which is basically written a measure at a time in this book. Instead of calling these chapters, I call them measures. At the beginning of each chapter, there’s a hand-written measure of music. You put them all together, you get a song called “The Lesson.” That’s what I was playing. I told them this was going to be a commencement talk, not a speech. And I just talked. I said things I’ve been saying for a long time, which is why I wrote the book. Students were saying, “Man, you’ve got to put this in a book.”

The way I share and teach music is different from the norm. But I also didn’t want to write a music instruction book. I didn’t want to do a manual. I don’t want a Wooten Method. I didn’t want to do something that people could argue about. So after years of staying away from writing a book, it finally hit me to write a story. I wish I could sell records like the book is selling.

What’s the first step when you begin work on an album?

For me, it’s a feeling. I’m not the kind of person who feels like he has to do an album every year. I’m not under any record contract. This time I knew that I wanted to do it with these three guys [saxophonist Bob Franceschini, drummer Dennis Chambers and vodalist Varijashree Vunugopal]. Of course, first I had to make sure that they wanted to do it. A lot of the time it’s just me at home. I have hundreds of ideas on my phone. It could be me singing in a car. It could be me at soundcheck. So I go through those ideas: “Oh, this is a good one.” I’ll write a few of them down: “Oh, these might go together.” I might take three recordings and put them in ProTools and play with them. The song starts there.

“I’m not trying to write a good song. I’m just writing a song. Then I make it good.”

I’ve never had trouble being creative. I learned a long time ago that the problem with writing a song is having to write a good song. I’m not trying to write a good song; I’m just writing a song. Then I make it good. I love Michael Jackson, but most of the songs he sings are not masterpieces: “The doggone girl is mine,” “Beat it, beat it.” The master is Michael, no matter what he sings. We’re gonna fall in love with whatever he sings. James Brown doesn’t speak clearly. Bob Dylan can’t sing. So my idea is not to write a good song but to just write something. And it usually comes out as something that I like. But I’m free in the beginning because it doesn’t have to be good.

Great interview thanks! I think his book should be mandatory in any Conservatory. Also, the idea of learning music with the same method we learn our primary language needs to be explored much more.

I saw them at the Knitting Factory downtown (Tribeca?) in 1997 — was it that show?