“I’ve always seen myself as a simple man.”

We were still fairly recent transplants from New York when my wife and I went to see Vince Gill perform at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium. I will admit that I hadn’t quite shaken off that East Coast tendency to dismiss everything west of New Jersey as a part of a cultural void. Vince’s performance that night clued me in fast about how wrong I had been.

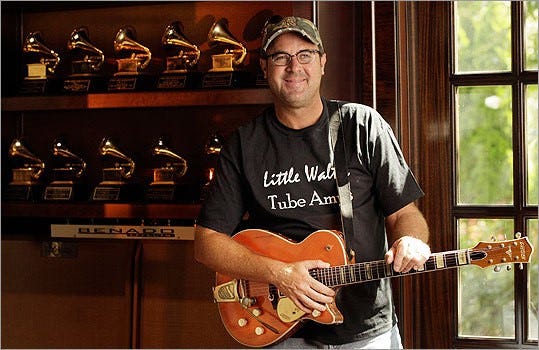

A few minutes after the show began, I whispered to her, “Wow, this guy’s great! His voice is amazing!” After another song or two, I added, “These songs are terrific! He sure knows how to write!” Then, following a guitar solo, “Holy crap! He’s a great player too!” I might have added that his stage demeanor was perfect: confident, witty, kind of shy in an aw-shucks way that only drew the audience in. But by that point I’d decided to just shut up and listen, which was what this 22-time Grammy Award winner, twice the recipient of CMA’s Entertainer of the Year honor and Country Music Hall of Fame member deserves.

In the years that followed I would develop a friendly acquaintance with Vince. We first talked at a release party for his monumental CD package These Days. Typically for Vince, he decided to host it with his wife Amy at their home. After playing some select tracks, he suggested we all just pop a beer or two and hang out with them. I’ve never been to a so-called industry event that felt more like a visit with friends.

This transcript is based largely on our conversation a few days later, again at his and Amy’s place, though I’ve added a few quotes from the USA Today piece we did ten years later. We did a few more when I was editing CMA Close Up too, but because the Country Music Association has denied permission for me to excerpt anything from them, I would like to share one revealing memory from one of those chats.

Unlike any publication for whom I’ve ever worked or written, Close Up maintained a policy of putting nothing into print or online without first giving the interview subjects an opportunity to read the final draft. Most of them approved it. Some offered factual corrections, which we added. A few demanded substantial revisions, including withdrawal of any controversial content; always, we made the changes they requested. But when Vince and I finished one of those Close Up interviews I told him I’d have a draft for him to review in a couple of days.

“Oh, that’s okay,” he said. “I don’t need to see it.”

This actually worried me; if I couldn’t document that any artist hadn’t read anything I’d put into the magazine, that could get me in trouble. “No, seriously, Vince,” I replied. “This is our policy. I’d really like you to look this over.”

He laughed. “Don’t worry about it,” he said. “I trust you.”

CMA never did learn that I let this one story run unvetted. Until now.

###

It’s been a long time since you released your recording debut with the EP Turn Me Loose in 1984. What has changed and what has endured in your music since then?

Oh, gosh. I think that going back and looking at my recording career in its entirety can be painful, you know? It takes a long time to really learn how to be soulful and how to learn the craft of, more than anything, what you don’t do, what you don’t play, what you don’t sing, all that kind of stuff. The willingness for brevity, the willingness for self-editing, to make the most you can with the least, has been the great thing to see from the start to this point. It’s no different that maybe an athlete would be in that when they’re in their prime and they’re young and their body is as good as it gets, and then the curve goes the other way. But for me, my ears tell me I’m the best I’ve ever been. I sing better than I ever have, play better than I ever have and write better songs. Especially songwriting: It takes a long time to learn the craft of writing good songs. Even in that process, you get going on a song and you go, “This is going nowhere. Instead of finishing this, let’s just bag it.” You don’t waste your time.

How do you improvise solos differently than you might have years ago?

I try to play appropriately. On some records, where all of a sudden the guitar player starts playing, you go, “Dude, you don’t need all that information [laughs].” That came from a lesson a long time ago. I was doing a session. I played what I played and the producer kindly said, “That was great. This time, play me half of what you know.” As a guitar player, I play like I would sing. And I feel like a singer. I sing like I would play. It all stems from my ability to hear. What do my ears tell me to play? It’s not what my hands tell me to play. It’s got to come from my ears and inside of me to get it to come out. I’m inspired by trying to find a new way to play the instrument, in a sense. As a musician, you never stop fussing with trying to make your tone better. It’s funny how much of that is in your hands, which you don’t realize as a young musician. You make the instrument sound the way it does because of your hands.

When you listen to your older stuff, do you hear it with different ears than you had then? Do you think, “I wish I had done this differently”?

Sure. It’s interesting how many things that I’ve recorded and never done again.

Why is that?

There’s only so much time in a two-hour show. I cringe at a lot of them. I’m not crazy about all of them. I’m crazy about some of them. But they can’t all be home runs. You can’t hit a home run every time you step up to the plate.

So when you write and record, you’re not necessarily doing it for posterity. You’re doing it for right here and right now.

I think so. At my age I feel a lot of angst in that I only have so much time left to be creative. When I was twenty I didn’t even think about it. I never saw the end. It wasn’t even a blip on the radar screen. But now I’m going, “Okay, what have you got? Twenty or twenty-five good years? Maybe more? Maybe less? Who knows?” You see guys like Willie [Nelson] recording their brains out and you just go, “I want to be like that.” I have so much inside of me. There’s so much music, so many songs, so many things that I want to sing and play. It’s a drag because you know you’re not going to get them all done.

So you don’t have days off. You write every day.

I don’t, no. I’m not an everyday writer. I’m probably in the night I write for a project [sic]. I’m kind of lying there. I already have all the songs in my head for the next album. They’re songs I’ve compiled that are a little quirkier. They might be a little more abrasive lyrically. They might be subjects that may not be real warm and fuzzy. I want to make a record like that, very pared down, maybe a trio with me singing these songs.

Why haven’t you recorded a live album?

Unfortunately, we live in an era now where we make a live recording and then “fix” it, manipulate it, change a few things, try to make it better, fix the words and the mistakes and whatnot. I don’t know. You know what I wish I had? A recording of all the sound checks. Now, that would be interesting.

It’s not too late to start.

Well, that’s true.

But then you’d know you were recording, not just setting up our live sound before a show.

Yeah. Once the red light goes on, everybody goes, “Better straighten up! Can’t be free anymore.” But sound checks over my lifetime have been so much fun. We’ll just find a groove and beat on it and play it and do a version of this song or whatever.

A Songwriter’s Quest

When did you realize that you wanted to write songs?

I started writing when I moved out to California, when I was nineteen and I’d met Rodney [Crowell] and Guy [Clark] and some of those folks. I said, “Well, shoot, maybe I’m gonna try to start making up some songs, see what I come up with.” I think I wrote seven or eight songs, then, the first ones I’d ever written. When I joined Pure Prairie League, they liked ’em and they recorded four or five of them. All of a sudden I went, “Oh! You’re a songwriter! You’re not very good but you’re a songwriter [laughs]!” That was the start for me.

Now I go back and listen to those songs and they’re so … I don’t want to say uninspiring, but they’re so young. You can tell there wasn’t much effort made. I obviously probably settled for the first thing that came out and onto the paper. But I told myself, “If I go down in flames, by God, I’m going my way, not their way [laughs].” At one point — and I never blamed the record company for this — I went to work with Barry Beckett and they instructed him that he wasn’t allowed to record any of my songs. That was kind of a heartbreaker for me. I don’t know that it was criticism but they did have a lot of constructive information too. I took that to heart and I did try to get better. I think in all honesty the reason I started having hit songs is that the songs were better.

“Songwriting is not fairy dust coming out of the air. You’ve got to work your butt off.”

How did that happen?

It’s a work ethic. It’s working harder, digging deeper or whatever you want to call it. It’s like playing an instrument: The more you do it, the better you get at it. When you realize that songwriting is not fairy dust coming out of the air, you’ve got to work your butt off and get in the habit of writing songs. The more you do, the better you get. The old adage is that you’ve got to write ten or fifteen songs to get a good one. I don’t know if that necessarily holds true, but this collection [These Days] may bear that out [laughs].

Can you think of a few songs that, if they’d never been written, you would have come out differently as a writer yourself?

One would be “The Randall Knife,” the song by Guy Clark. I played on Guy’s original version. I was just destroyed by that song. It completely undid me. It had so many things in it that reminded me of my life with my father. My Randall knife was a golf club and a four-iron that my dad said I broke. I went and got it fixed and never told him. I finally told him when I was about thirty years old and he still kicked my ass over it [laughs]. So there was such an interesting parallel for me in that song. I just wept and wept as we were recording it. I knew that I wanted to hear that song at my dad’s funeral someday. The ironic side about that was that my dad died when I was forty, just like Guy’s did in the song. All these parallels were kind of eerie, you know? When I wrote “Key to Life” for my father, it had a reference to “The Randall Knife” in it. That song goes in all sorts of ways for me.

Any other pivotal songs?

Probably “’Til I Gain Control Again” by Rodney. I was in a band, singing that song, when we opened for Guy back in 1976 or ’77 at the Troubadour. I sang that song, not really knowing that Rodney wrote it. But he was there. He came up after and introduced himself. That song was the beginning of an amazing friendship. I’ve sung with Rodney about a hundred times since then. He was a great mentor. Both of those guys were amazing mentors to me. They still are. But that was one of the first songs I wanted to learn. Every now and then you’re drawn to want to learn a song and sing it. That one was one for me. That music that they were making, Emmy [Emmylou Harris] and all of them, was so inspirational to me. But that was probably the song that takes me all the way back to when I first got pointed to what I wanted to do. It’s just a gloriously beautiful song.

Just One Change

On These Days, you devote one of the four CDs to mainly stretching out and jamming. The first one, “Workin’ on a Big Chill,” is mainly a one-chord vamp, so clearly it has a different intention than the ballads.

It does. That’s very reminiscent to me of “All I Really Want to Do Is Have Some Fun” by Sheryl Crow — you know, everybody having a good time on the weekend before they gotta go back to work. The truth is that the rockin’ record is the vehicle for me to rip on the guitar for the most part. It’s funky, it’s a deep groove and it’s fun to play with the guitar. We’re not recreating War and Peace; we’re just talking about drinking some beer and hanging out with your buddies [laughs].

Anyone can jam over a one-chord vamp …

Well, that song doesn’t really slide into that one-chord vamp until the outro. To me, it’s all about when you’re in a band and you’re trying to put things together: You provide the foundation. What’s neat about the ending of that track is that it’s not just the guitar blowing over the top of it. Bits and pieces of everything come out. That’s the beauty of musicians playing together, the push and pull and listening to each other. What I play will inspire that guy and vice versa. There’s a real art to that. The real ticket to what great musicians do is, they listen to each other and they edit themselves. That’s what separates a good musician from a great musician.

Do you think about combinations of musicians on each track as you get ready to record?

Sure, because you know how certain guys play. Which guitar players do you cast for certain songs? Which guitar players like certain genres of music? There’s so much more intimacy in the casting than there is in trying to get somebody to do something they don’t normally do. It’s kind of like going to McDonald’s: When you order a cheeseburger, you know what you’re going to get [laughs]. I guess it’s pretty awful to confuse a musician with a cheeseburger.

Maybe KFC is the better analogy because you’ve got traditional and extra-crispy options.

Boneless wings [laughs].

What are some great one-chord songs? And what makes them great?

Some of them rock it back and forth. “Cocaine” by Clapton would be one. [He hums the song’s central riff.] That’s the foundation that you get to solo over. If you get to sit on something for a while … Having more chords is not necessarily advantageous for soloing. To me, there are times it’s just like riding down the river, man. You just stay on that thing. Look at the music of James Brown, that really funky R&B stuff. It was all about finding a groove and sitting on it and never wavering from it too much. For some of those things, that’s the beauty of it. On some of the ballads, the big chords and big changes are what makes them interesting.

That’s why casting the musicians is so important for a blowing tune.

Yeah, but some of the stuff is not labored upon to the magnitude that people might think. The spontaneity that musicians have … Their first impulse is generally pretty spot-on. You want to be prepared to capture that. It’s really important to me that when solos and stuff, I want the sound to be so good right off the bat because what you’re gonna play with the most spontaneity is generally what’s good. You can play a solo and then work on it, work on it, work on it. then you go back to, “Where did I start?” Sometimes where you start is horrible. But sometimes it’s exactly right. You just wind up enhancing what your mindset was as a first impulse.

You learned that lesson early on, from playing in other people’s bands.

Sure. Once again, I think that brevity and editing are the things that you learn instead of playing more. You wind up saying, “How could this work better with six notes instead of twelve notes? Okay, now how about four notes instead of six notes?” You try to say the most with the least. Be minimal with what you do. I really feel that what’s … not wrong, but not good … about some music is that it takes up so much space. There’s so much crammed into one space. I love when you take a song like “I Can’t Make You Love Me” by Bonnie Raitt. It’s just this amazing voice, sitting on this bed of space. It’s the greatest thing ever.

Riffs, Harmonies, Modulations

The songs aren’t terribly complicated on Some Things Never Get Old, the CD in These Days that’s devoted to roots-oriented country music. But they do allow room to illuminate the unison riff the guitar and the bass might do throughout the performance, like on “Out of My Mind” and “This New Heartache.” How do you find the perfect riff to tie these types of tunes together?

You’re always searching for it. I think people miss the point about where a lot of great records gain their identity, whether it’s “Day Tripper” or “Brown Sugar” or “Sweet Home Alabama. To me, musicians don’t get near the credit they deserve for these kinds of things. We always play that game on the bus where we’d put on the satellite radio and have to guess who the artist was by the intro. When the singing started, the game was over. But you had to know that steel guitar intro or that fiddle intro and those kinds of things. They’re really unique in terms of how much identity they gave to songs. That’s what makes a record special: the intros, the turnarounds and those kinds of things.

But also the harmony is where you find unique ways to be different in each little place.

That’s probably where I’m most creative, in harmony singing. You get people in there that have stuff you normally probably wouldn’t hear. Like, there’s a guy called Wes Hightower. He’s the main cat who sings on everybody’s records in town. He’s fun to work with because he can do every little idiosyncrasy that you might want from someone that fine-tuned. With other people, you’re looking for performance. Emmy [Emmylou Harris] is not a precision-perfect type of harmony singer, but her voice is so amazing, the way that it floats. The way that she hears harmony is kind of unique. It's so special.

I can remember when I was sixteen, I guess, and I heard Emmy sing on the Linda Ronstadt record [Heart Like a Wheel]. I was as moved by the harmony singer as the lead singer. That’s just how I always heard music; not everybody does. But I’ve always loved Don Rich as much as I love Buck Owens. Phil Everly was as important to the Everly Brothers as Don ever was, even though he was the harmony singer. The supporting cast has always, in a sense, been more important to me as an artist. It’s not, “How can I get famous people to sing on my record?” It’s just how I hear things all the time: I know that voice and I think it would sound neat here.

One of the most important differences between where you are today and where you were when you were back then is that you can pretty much pick and choose anybody for any track.

Well, yeah, but it’s in keeping with what I’ve always done, whether it was Emmylou singing with me on my first record [The Way Back Home, 1984] or Reba singing with me in 1989 or Rosanne [Cash] doing a duet with me [both on When I Call Your Name]. To me, the process is always about collaborating.

And you’ve made lots of guest appearances on other people’s albums. It doesn’t seem that hard to persuade you to sing on someone else’s recording.

That was actually what I aspired to do. I had just as much interest in being a session player and singer as I did to be an artist. I still do. It’s a much harder job. I don’t think people understand that. You wouldn’t expect them to. But when I have to follow what somebody else has done, that’s harder than you getting to be the one who does what you do and everybody has to support you. To me, that’s more of a testament to talent than fame, to get those calls to sing a background part or play a guitar solo or what have you.

Some of the songs on These Days stretch traditional structure. “The Sight of Me Without You,” for example, has some irregular bar lengths. How do you decide when a song needs to hit a chorus two bars early, let’s say, or otherwise do something different?

To me, it’s the right thing to do when a song doesn’t need to sit there for two more bars before you start the next bit. Plus, it’s a ballad, so that kind of gives it a lift. Country songs have done that to me at times: “Okay, we don’t need to plod all the way through this. It doesn’t have to be even.” That’s why there are turnarounds. And the turnarounds are unique: It might be on the first half of the verse and the last half of a chorus.

Another thing is, there have been a million key changes throughout country music, sometimes on each verse, because I think you had to find a way to make it musically interesting. A straight country song by itself, just played in one key, can sound tired. So you go up a half step for the second verse. Look at George Jones’s records: They have tons of modulations. It’s just a tiny thing, but it changes the space a little bit.

I once asked Barry Manilow about that and he apologized for all the key changes: “I can’t help it! That’s just the way I write!”

[Laughs.] I’ve got a friend who says that every time he hears a song with a modulation, he stands up and cheers. You’ve got to make fun of it! A lot of times modulations happen because things are starting to get boring, you know?

You bump up the chorus up by a step on “What You Don’t Say,” from The Reason Why, the ballad CD in These Days.

Yeah, but it wasn’t just, “Okay, we’re gonna raise it up a half step on the V chord and bang, we’re into the big chorus.” I was really musical [about] how it got there and how it got out of there, where it was huge and then it went back to that moody arpeggio guitar thing of the intro, which George Smith did. That’s what I think is unique about this song, how it gets back to the original key.

Another new thing for you on These Days is the track you sang with Diana Krall, “Faint of Heart.” How did you begin writing that tune?

To me, it sounds like a song that could have been in the Forties, like a jazz standard. I just felt like, “Keep an open mind. Let’s write a jazz tune. Who cares? Nobody’s gonna lose any sleep over it.” It’s authentic. The changes are legitimate. That was the most important thing, to not look like a rube, a country guy trying to be a jazz singer. Puh-leeze, you know [laughs]? I think I’ve got enough musician in me to tell me when it’s authentic.

That line from the first verse, “pour me one more on the rocks,” isn’t a typical country lyric.

Heck, no! I’m just thinking, “I’m in a really cool martini bar.” It’s sultry, man. I could have recorded it any number of ways with any number of people, but from Day One when I wrote it, I wanted to get it to Diana to see if she had any interest in it. And I didn’t give in.

Stories and Stills

Along with heart, feeling and craft, I hear a lot of clarity in your songs. Your characters and stories are all crystal clear; they’re easy to access. So as a writer, were you in any way influenced by writers like Bob Dylan, whose lyrics are often more elusive and figurative?

Hmm. Boy, I gotta be honest. He had a kind of wisdom that went beyond being a songwriter. To me, he was like an old soul. Old souls are characters that are timeless, who feel to me like they’re hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of years old. They’ve seen it all. But, I mean, you can go back and listen to certain songs and go, “You know, I could read every book that’s ever been written and I’m still not gonna get that. I don’t know what the hell they were talking about. There are often times I don’t really get it, lyrically. And that’s someone where the lyrics were ninety-nine percent of it. It’s not going to be to that extent [with me]. There’s so much more musician in me that I don’t think I’ll ever get to those depths.

Not that you’ve ever even tried …

Well, I have my way of seeing the world. I have my way of seeing relationships and my way of seeing how our culture is, this and that. All I can do is what I have come up with in a sense. I just can’t imagine myself … I don’t know. I don’t want to sell myself short. But I’m also being honest.

“My personality will never allow me to promote myself.”

Of course, you write songs both for yourself and for other people to cover …

Well, the number of people who have recorded my songs is not very big. But the ones that have, it’s been pretty neat [laughs]. See, my personality will never allow me to promote myself. I’m not ever gonna be good at picking up the phone, calling somebody up and going, “Hey, I’ve got the perfect song for you.” It’s not in my makeup. Never will be. The times that I get my songs cut by anybody else, it’s completely accidental, I assure you [laughs]. If one of my songs was being pitched to Kenny Chesney, say, I can’t imagine he wouldn’t say, “Well, if this is so good, why isn’t he doing it [laughs]?” I can’t help but think this way! Bruce Hornsby gives me grief every time I see him: “I can’t believe you passed on ‘Mandolin Rain’ [laughs].” Well, it was the Eighties. I was an idiot. What can I say? Maybe that might change now that I’m not one of the really big guns going full blazes in that world, I think I will try to really brand myself as a songwriter and see if people wouldn’t be interested in some of these songs.

That’s another thing. There was a big reason behind the way this turned out. I had so many songs written that I really did like, you know? I said, “Dang it, I’m so tired of writing some neat material that never sees the light of day. I really think people would find something interesting about some of this stuff that’s not the norm for me.”

Common Threads

For all the genres and subgenres you explore on These Days, is there something that ties it all together?

Well, I’ve always seen myself as a simple man. I didn’t set out to write different songs about love. These just seemed like the ones I like the most, the ones I should do. I could say at least that they’re not all about trucks [laughs].

I’ve always seen myself as heartfelt when I write songs. They’re not gonna be as adventurous or as deep as maybe Rodney [Crowell] or Guy [Clark] would write — people that I admire. If you listen to a Guy Clark song and he’s telling you a story, you not only understand the story but you also see the story. You see the pictures. To me, that’s the point of a song, to put you in that place in the story and respond to that story. I like doing that. That’s where I find myself feeling more like a songwriter, on songs like “Key to Life” [from The Key, 1998], which I wrote about my dad “Go Rest High” [from When Love Finds You, 1994] was somewhat like that, not too much. “Jenny Dreamed of Trains,” which I wrote with Guy. “This Old Guitar and Me,” “Whippoorwill River,” which I wrote with Dean Dillon. I really like stories. Unfortunately, where I’ve wound up in the big picture, I try to be an artist and try to cut hit songs and get on the radio. And some of those things can either limit what you can do or you don’t have as many opportunities to write as many story-songs as you would like, even though that’s what I’m drawn to the most.

“When somebody is kind, it makes all the difference in the world.”

Sadly, younger country music writers seem unaware or uninterested in that part of the genre’s history.

I would encourage them to look a little deeper than the Top 15 on the charts. But that’s the case in any format. Just because this particular artist is on the top, whoever it is, whether it’s in the pop field or the country field or whatever, trust me, there’s one at the top but there’s a hundred that are worth hearing if you’ve got the time to go and find them. Most people don’t have the amount of spare time that we used to have. When we were kids, we’d sit and listen to records all night long: new records, different records, things we were trying to discover. But this is an information age. There’s so much information being fired at us that the attention spans most people have are not comparable at all to what we used to have. You watch a TV screen and there are eight pieces of information, on the bottom, one going down the side and another one at the top.

For a long time I’ve heard people say, “If it’s commercially successful, it’s not any good.” And that’s not true. It’s all what it is. The results of something’s success or failure don’t really validate it as good or bad. None of the notes change on anybody’s record depending on who likes it and who doesn’t, how many people hear it and how many don’t. You can look at any situation and find the worst in it or you can look at a situation and find the best in it. I’m married to a woman who finds the best at everything. I’m not that good at it. I wish I was better at that. But I always listen to the critical ear, trying to take it all in and formulate an opinion on what I think about it from a critical place. I think we’d all be better served if we’d just dig a little deeper.

Hasn’t the Americana movement spurred young writers to return to that narrative tradition?

At least they’re asking. In any era, you could find a group of guys playing down here that are.

At the end of the day, that’s what I’m grateful for. I still have a handful of my heroes around, so in some part of my life I still feel like a kid, but not as much. Little by little, all of those heroes are going to the other side. What’s great is that they’re so welcoming and gracious. Those are the ones that inspire me the most — someone like Little Jimmy Dickens. He may not want to hear you go up there and thrash away on whatever you’ve got going on, but he’s going to make you feel welcome. I’m not going to be that naysayer guy who goes, “You’re not as good as you used to be.” There’s no point in that. You can be welcoming, you can be supportive, encouraging and all that kind of stuff. That’s all any of us ever want. We’re so vulnerable to stick our necks out like we do, to put ourselves in front of people to either be embraced or criticized. It’s a pretty tough place. At any point, when somebody is critical of you, it doesn’t feel good, even if you’re successful and you can go, “Hey, up yours! I don’t need your opinion.” But when somebody is kind, it makes all the difference in the world.

I mean, that’s the whole point, the point of any of us doing this. You might find a handful who are in it only for monetary gain. But to all of us who got good enough to learn to play well enough, to write songs well enough, to get an opportunity, we did it because we loved it. If you ever lose sight of that, that’s when you’re in trouble.

###

Taking notes, and reflecting that many of the best songs I’ve been part of had the elements Vince mentions but without the intellect of having done it on purpose. Those will be more purposeful next time.

A lot of songs named in this article I hadn’t heard of. Will listen. Thanks for this awesome, unique and inspiring blog!n