Twice in my career my interview subjects have lapsed in and out of multiple personalities. Even stranger, they did so only when I asked them to. The second of these subjects was The Cleverlys, a group of bluegrass musicians who adopted a hillbilly persona onstage. They were one of many country artists I interviewed on video at the Country Music Association while on the job as editor of CMA Close Up. Those interviews were archived but, as far as I can tell, have been taken offline. I can only hope someone will post them someday; there was lots of good stuff in that footage.

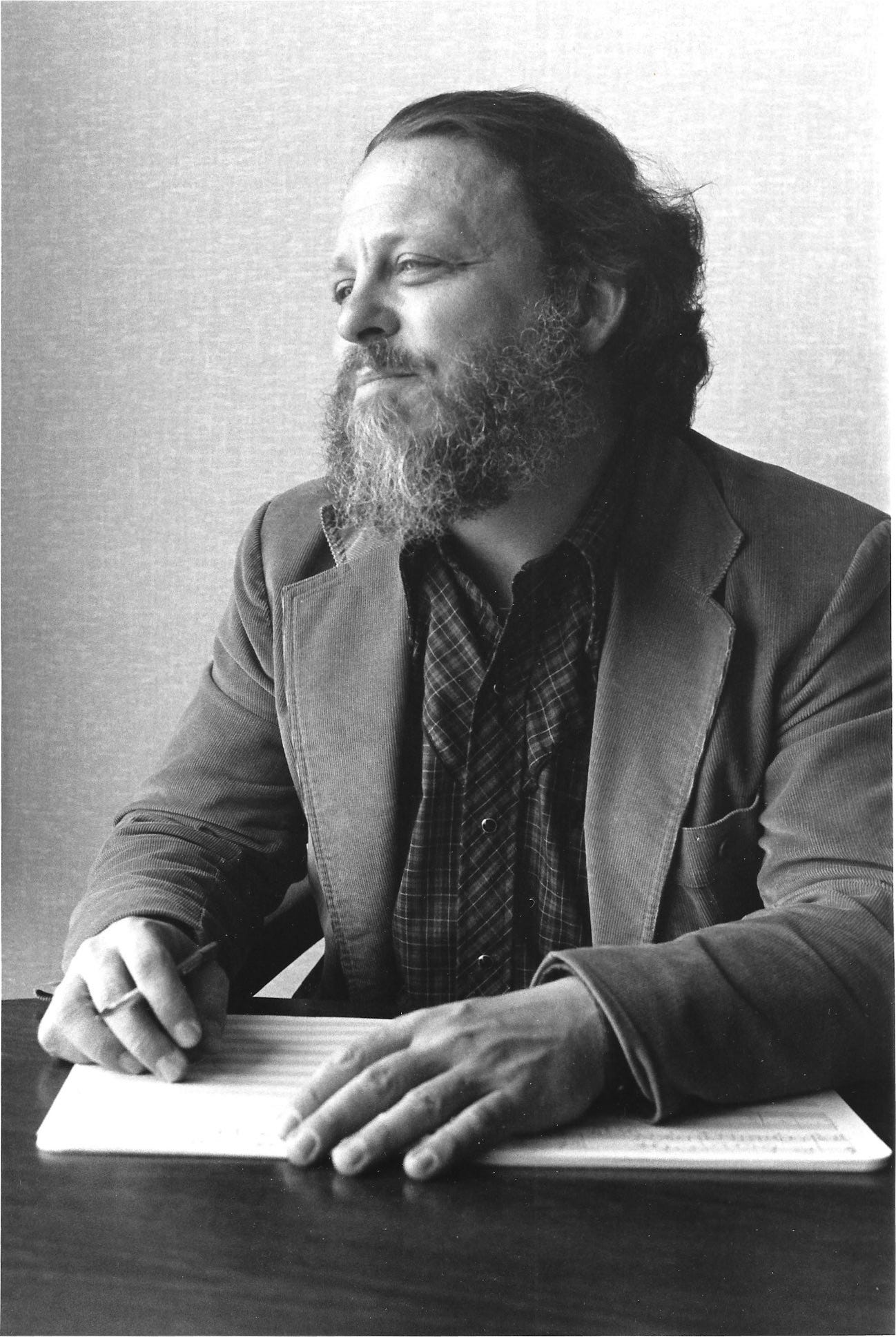

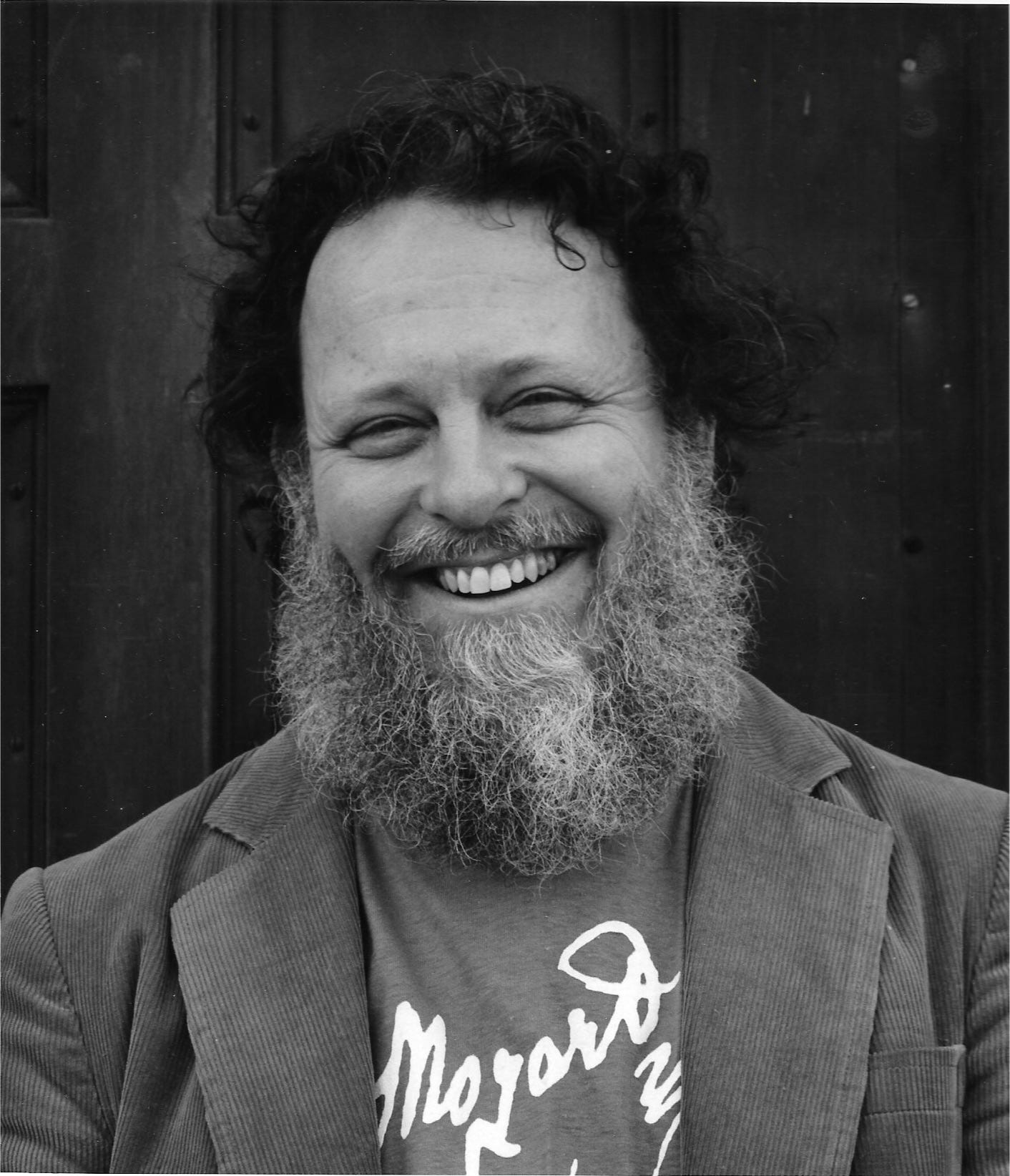

The first, though, was Peter Schickele, in my view the greatest of all musical humorists. A serious composer, performer and pedagogue, he was also riotously funny, whether in or out of his character as P.D.Q. Bach, mythic but celebrated son of the immortal J.S. Bach and composer of Concerto for Horn & Hardart, a Toot Suite for calliope, operas such as The Stoned Guest and A Little Nightmare Music, an UnBegun Symphony, and of course his Pervertimento for Bicycle, Bagpipes and Balloons?

The night before our interview, my wife Beth and I attended his PDQ concert at San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House. Maybe five or ten minutes after the show was to begin, an ostensible representative of Professor Schickele’s walked onto the stage, before the curtains. “I’m so sorry,” he announced. “But it seems that the professor missed his flight from New York here to San Diego.”

After the laughter subsided, he continued. “So regretfully, I’m afraid we have to declare the evening at an end and refund your tickets. I apologize for the inconvenience …”

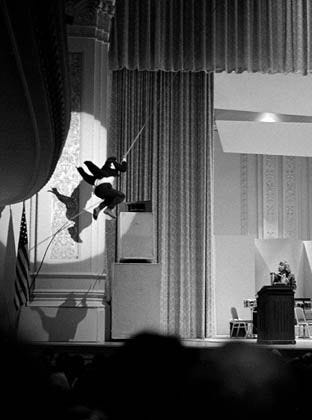

“Wait! I’m here!” The voice rang from the back of the balcony. The lights swung in its direction to reveal Schickele, his hair disheveled, his tuxedo in wild disarray. He ran down the aisle, grabbed a rope that was conveniently suspended from the ceiling, and swung Tarzan-like over the floor seats and onto the stage as the audience cheered him on.

After composing himself, Schickele announced that he would now lead the San Francisco Symphony in a performance of PDQ Bach’s Symphony for Gradually Arriving Orchestra. I should say here that I’ve searched online for information about this unforgettable piece and found no results. Maybe it was a one-off of some sort. But I’ll never forget it. The curtains opened to an empty stage. Seats for the orchestra were laid out but there wasn’t a soul to be seen. Holding his arms up dramatically, Schickele then plunged into an exhibition of conducting excess, shaking his fist at nonexistent musicians to indicate a furious crescendo and so on. This went on for a few minutes, until one woman traipsed in from the wings, a case in her hand. She took her place on one of the chairs, opened the case, put her oboe together and then waited for Schickele’s dramatic cue, at which point she began her somewhat forlorn part.

As the piece progressed, more musicians wandered in. Bit by bit, the stage filled and the sound swelled. Eventually, after many ridiculous musical puns and punch lines, the ensemble had raced into one of those finales that early Romantic composers loved: slow, then faster, alternation of I and V chords, timpani thundering, conductor thrashing melodramatically … until, with seconds to spare, an errant trombonist, clad in raincoat and holding his instrument, sprinted through a door at the back of the auditorium and onto the stage. Perfectly timed, Schickele pointed to him, he played a vaudeville slide and the audience roared.

My wife and I stayed that night in the Inn at the Opera, steps away from the auditorium and at the time our favorite escape in San Francisco. The next morning Schickele and I met in the downstairs restaurant. After a few minutes, for the only time in our marriage, my wife came down from our room and said, unconvincingly, “Oh, I’m so sorry for interrupting, but our coffee maker doesn’t seem to be working,” or whatever she came up with. The fact is, she was as dazzled by Schickele as I was. Neither he nor I was bothered by the distraction in the least.

(Note: Our conversation stretched on for nearly two hours, so I’ve trimmed the transcript a bit. Deletions are indicated with an ellipsis: …)

***

What attracted you, as a musical satirist, to the music and character of P.D.Q. Bach, rather than to someone from, say, the Romantic era?

Definitely the answer to that is the old truism that many people never stop to think about, which is that satirists make fun of what they love, not what they hate. Just as Anna Russell trained to be an opera singer and Victor Borge to be a concert pianist, I studied to be a composer, and Bach and Mozart are two of my favorite composers. I never sat down and said, “Now, what period would be good?” I just fell into it because of the musical affinity. I’ve been doing P.D.Q. Bach publicly now for more than twenty years, and if it were P.D.Q. Wagner or P.D.Q. Strauss or some composer I don’t have much affinity for, I would have been bored with it a long time ago.

The handy thing about P.D.Q. Bach being a son of J. S. is that he had a connection both to the Baroque style of his father and to the Mozart/Haydn style of his contemporaries, so a lot of his pieces are actually more Mozartian than they are Bachian.

Yet P.D.Q. Bach pieces do often deviate wildly from the style of the time.

Several of them do have musical traits that foreshadow late trends. There are certainly bits of rock and jazz and all sorts of stuff in P.D.Q. Bach. It’s hard to imagine him doing a whole piece like that, but I can certainly imagine him slithering in and out of it. The whole thing of expectations is very important. If you know what to expect, then you will know when the music veers from that. Part of the problem with doing takeoffs of contemporary music is that we live in a completely laissez-faire age artistically. When you have serious musical events that consist of pushing a piano offstage into the pit or chopping it up, it’s hard to top that in a comedic way.

There was an exploding piano bench in P.D.Q.’s Concerto for Piano versus Orchestra, though. Do you have these effects in mind when composing — pardon the pun — these pieces?

Sometimes the germ of the piece is the effect. Sometimes as I’m putting it together these ideas come to mind. There’s a piece I’m working on now where all I have so far is a theatrical event at the end. It will grow from that.

…

Is there something humorous in the piano itself, or in the psychology of the keyboard player, that you don’t see in string players, for example?

Well, one aspect of concert life that I think does get a little ridiculous sometimes is the posturing of the soloists, and pianists are usually the worst of the lot. But when I was a boy in Fargo, North Dakota, I remember hearing a recital of Mischa Elman, who was quite old then, playing Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” Sonata. There’s one variation in the theme and variations movement where the music is all about the piano and the violin just has little afterthoughts. But Mischa Elman was not about to let that pianist have the stage. He played those little phrases as if they were the biggest things in the world. I would say that he was tops when it came to posturing. But pianists are just as famous for singing along, hopping up and down and all the stuff they do. Along with whatever it is musically, the Concerto for Piano versus Orchestra is a compendium of things I’ve seen pianists do.

Did you have any specific pianists in mind as you developed your stage character?

Sometimes yes and sometimes no. I was fortunate enough to have heard Glenn Gould perform before he quit the stage, and although I think that some of the stuff he did was completely wrong, he was one of the most fascinating and spectacular pianists around. The whole business of singing along while you play is something that I remember him doing when he played the Goldbergs. And the thing of bending over until your forehead is practically touching the keys is something I associate with him and a couple of other pianists. Some of the mannerisms I don’t associate with any particular pianists, however. I just know I’ve seen them somewhere.

What about pre-piano keyboards, such as the harpsichord?

Well, that’s a little different, most obviously in that you don’t have physical mannerisms associated with the harpsichord. Also, I haven’t used harpsichords as much as the period might indicate, partly because I do so much touring and you’re never sure what you’re going to end up with when you ask for a harpsichord.

You have used it, though, in some large-scale P.D.Q. Bach pieces, such as the opera Hansel & Gretel & Ted & Alice …

… An Opera in One Unnatural Act. That’s one of the most interesting pieces as far as keyboards go. There are three people in the cast, but the opera company P.D.Q. Bach was writing for was so cheap that the two actors not only have to cover seven roles, but they also have to play harpsichord and calliope in in the overture and finale to fill out the orchestra. And in the Twelve Quite Heavenly Songs, which is a song cycle based on the signs of the zodiac, you have one pianist sitting in the middle of a square flanked by piano, harpsichord, calliope and push-button chord organ.

When P.D.Q. Bach writes for harpsichord, is there a limitation in that you lose the piano’s dynamic element as a resource for humor? Is he forced to restrict it to melodic puns and jokes?

You do lose that continuum of dynamics. But the good harpsichord composers, and I’m thinking particularly of Scarlatti at the moment, were tremendous at changing the dynamics by how many notes they used. … One of the pieces in the Notebook for Betty Sue Bach, called “The Reign in Spain,” was was definitely influenced by Scarlatti, but it’s equally obvious by the range that it’s a piano piece.

This has nothing to do with P.D.Q. Bach, but in my experience one of the things that makes J. S. Bach and Scarlatti stand out among Baroque composers is that their keyboard works seem to translate well onto piano. The music of other Baroque composers tends to sound exceptionally thin on piano, whereas Bach’s rhythm and line, and the color of Scarlatti, come through very well. I have a record of Glenn Gould playing Elizabethan music. He could pull it off, but I don’t think many people can.

Did you receive much training on harpsichord?

Not seriously — not even seriously on piano in any sense of being a concert pianist. It’s something that I regret very much. I wish I could play the piano better. I’ve known since I was a teenager that composing was what interested me. As a matter of fact, my problem when I studied piano as a teenager was that I always ended up writing instead of practicing. To this day I have a very odd technique.

In what way?

There are certain areas of classical keyboard training in which I’m very weak. I can’t play an even scale with my left hand to save my soul. I would never get up and play other people’s music — only P.D.Q. Bach’s or my own. My technique takes care of the music I have written and the P.D.Q. Bach pieces I have discovered that I want to play. But there are Peter Schickele and P.D.Q. Bach pieces I would not attempt to play myself.

What are some of the more challenging pieces in the P.D.Q. Bach oeuvre?

A couple of the pieces in the Notebook for Betty Sue Bach re somewhat virtuoso-istic. There is one isolated chorale prelude that I discovered and played on The Today Show a while back. It’s interesting in that the texture is established by the two hands playing very far apart at the bottom and the top of the keyboard. There’s considerable question of how the chorale melody isle is played. That melody, by the way, is “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star,” which Mozart himself wrote variations on. It turns out that the theme has to be played by the nose. In its own way, I would call that a virtuoso piece. I’ve established that this is part of a little notebook P.D.Q. wrote for his uncle, “Piggy” Bach. It will be published as soon as I’ve discovered the rest of the pieces.

P.D.Q.’s Abassoonata for Piano and Bassoon, played simultaneously by one performer, also seems to pose technical challenges.

That may be the hardest P.D.Q. Bach piece there is. I practiced that piece over a period of time. It is hard as hell. The hardest part is the least flashy-looking part. It’s in the third movement, where I’m playing the piano with my pinkies and the bassoon with my elbows.

“We do this piece, The Goldbrick Variations, where the fuse keeps being blown and the lights keep going out.”

So you’re able to write or “discover” keyboard pieces beyond your technical reach?

I do that sometimes. My Quartet for Clarinet, Violin, Cello and Piano has a piano part I wouldn’t want to have to play. It’s not that I couldn’t hack through it if I rehearsed, but I just never intended for me to play it. Now, David Oei, pianist in The Intimate P.D.Q. Bach Show, is a real virtuoso. It’s so fantastic in a comedy program to have someone like him. We do this piece, The Goldbrick Variations, where the fuse keeps being blown and the lights keep going out. The genesis of that piece came late one night, when I was driving back to New York from Philadelphia with David. I kept telling him that I wanted to do some new pieces for The Intimate P.D.Q. Bach Show that really showed him off. He said, “Well, Peter, I don’t know if this gives you any ideas or not, but anything I can play I can play in the dark.”

The choreography of the Goldbricks involves you and Peter quickly displacing each other on the bench without interrupting the keyboard part. Was that hard to work out?

Oh, no. When you’re doing a piece like that, you have to rehearse the moves as much as the notes.

…

You’ve worked with Leonid Hambro as your “straight pianist” too, haven’t you?

Well, not really. Lee played the harpsichord on Iphigenia in Brooklyn and he played the very first public P.D.Q. Bach public concert in 1965. But that wasn’t a long-term relationship in terms of touring or anything. In that sense, David Oei is the only pianist I’ve worked with. He’s been with the Intimate show since it began fourteen years ago. Lee was Victor Borge’s straight man. What was funny about that was that Borge is always completely serious onstage. He never laughs. But Lee couldn’t stop laughing when he was working with Borge, because Borge is so funny. So finally Lee just built his character around that. Borge said to him, “Go ahead, crack up all the time. That’ll be your thing.” What that did was to accentuate Borge’s straight face.

Have you ever thought of going into musical humor from something other than a classical perspective? Or is there something in classical music that pulls you in that direction?

That’s an interesting question. The thing is, I never started P.D.Q. Bach with the idea of it being anything as long-termed as it turned out to be. I just did some concerts at Juilliard and Aspen for the rest of the school. I’ve worked a lot of areas in music. In fact, I recently finished a concerto for bluegrass band and orchestra that was commissioned by a band down in Kentucky. But my core background really is classical, so maybe that’s where I feel most secure. Also, in extramusical terms, there is that whole business about the stuffiness that is unfortunately associated with a lot of classical concerts. That is particularly fruitful ground to explore.

…

I have always always done both the serious and the funny, ever since I was a teenager. I divide the year approximately in half, the winter being devoted to P.D.Q. Bach and the summer being devoted to Peter Schickele. But it’s true that I have always wanted to get a synthesis of all the folk and jazz and rock stuff I like, in addition to the classical. Just wanting to do that doesn’t make it easy to do. A lot of the third-stream pieces in the late Sixties that tried to combine jazz and classical were self-conscious and didn’t really work. But I’ve been writing music for more than thirty years now, and over the years it so happens that a lot of rock and jazz figures, a lot of drones from Eastern and folk music, and things that hang together to me in a pretty natural way. …

Beyond the Classical Fringe

One of your first rock-influenced works, the Serenade for Piano, was written in 1961, when rock was still in a pretty basic musical state. What did you hear in it that you could draw from for the Serenade?

Well, I was a great fan of the pre-Beatles, late Fifties stuff. I really liked the Everly Brothers — not just the Everly Brothers but the songs they sang, in spite of their determinedly teenage lyrics. They tended to have modal melodies, and their use of melody was folk-like, rather than like Forties pop songs. And they sang like angels! I remember the first time I heard “Wake Up, Little Susie.” I was in a diner or somewhere like that. The harmonies just grabbed me. Then I can remember when I was a student at Swarthmore. I would go into the student lounge and play songs by Elvis Presley and Ray Charles and Fats Domino. That would get raised eyebrows from some people, because I was always the big music major in school.

One of the things I always liked about Fifties rock was the figures. In other words, forget the melody but listen to the figures. The Piano Serenade has a bass line that is very much like what you heard in Little Richard’s “Lucille” and in a lot of Fats Domino songs. I moved that figure around in a very simple blues way, just like on a lot of those simple-minded but nifty Fifties things.

By the time you began doing arrangements for singers like Joan Baez and Buffy Sainte-Marie, a more sophisticated element had credit into pop music.

Right.

In some ways, that really was the heyday for serious classical composers who were exploring the folk-rock format.

I was just going to say that. Your word is right. There was a period in the late Sixties that was a heyday for that kind of thing, when I was doing that stuff and Joshua Rifkin and Bob Dennis were working with Judy Collins.

As someone with a lot of criticism about contemporary classical music, I was really hoping that this fantastic beautiful explosion that was happening in popular music would go on. It was really a folk music explosion, although a lot of people don’t tend to think of it that way because some groups made a lot of money. But it was folk in the sense that every kidding the country had a guitar and was writing songs.

What brought that heyday to an end?

At the end of the Sixties, everybody started going to Nashville and a completely different thing happened. They started doing head arrangements, working with musicians there for a very country sound. So that synthesis didn’t happen immediately. But I think that it may be happening over a longer term than I thought with that whole minimal thing that Philip Glass, Steve Reich and Terry Riley are doing. I know a lot of those guys. Philip is an old friend of mine, and when he was throwing on a tape or a record it would more likely be Elton John than classical music. And I listen to rock much more than classical these days, so there’s definitely an influence. Even though they don’t use rock figures specifically, they bring the rock influence back to classical music in the form of momentum or a feeling of infectious rhythm. It drives some people up the wall.

When you think of the post-Webern school, you never get a feeling for a beat at all. There was one movement in the Boulez Marteau Sans Maitre that had a regular beat, but I read a couple of years later that he didn’t like that movement too much anymore [laughs].

…

Madness In The Method

How did P.D.Q. Bach compose? Did he write at the piano?

Of course, each composer has his own way of working. Some composers work at the piano, some work away from the piano. It’s been fairly well documented that P.D.Q. Bach wrote under the piano.

From what I’ve heard, Professor Schickele, there are important differences between how you and P.D.Q. Bach compose for the piano. For example, on pieces like “To His Coy Mistress,” from the Liebeslieder Polkas, he displays a fondness for playing one note over and over again as a kind of elemental motif.

It’s an interesting point you bring up. That may be one manifestation of his limited intellectual ability. He had to play one note a lot before he could decide what to do next. Last week I played his Concerto for Piano Versus Orchestra, and there’s a place where there are a whole bunch of Gs played in a row.

My theory is that this may be his way of avoiding the dreariness of doing thematic development and variation as long as possible.

That could be. I once developed an interesting theory about P.D.Q. Bach, that his music is based on a one-note row and that every single note in all of his pieces can be thought of as a transposition of that one note.

Scales also seem to show up a lot in his music — simple, classic and boring. Was this his way of rebelling against all of the practicing he may or may not have done as a kid?

Either that or making use of that practicing. I’m thinking of a couple of his Twelve Quite Heavenly Songs, where scales run up and down and up and down in the piano part. I think it was probably his way of figuring that if he had to sit there and practice all those scales, he might as well make use of them.

“My personality as a composer is very melodic and lyrical, unmathematical and unthorny.”

I think I’m beginning to understand why Chick Corea once described you as the most inspiring teacher he’d ever had at Juilliard.

Chick was in my General Literature Materials of Music class. It was very nice of him to say that. I hadn’t heard him play at that time, but he certainly stood out in that class as being way above the general level. I’m a fan of his too.

Do you have any ambitions to teach again?

I enjoy teaching a lot. I love performing, and I regard teaching as an aspect of performing, not in the sense of being hammy but in the sense that explaining something is a bit like presenting a melody. Also, I’m comfortable up in front of people. But in ’64 and ’65, when I was at Juilliard, I found that I was spending less and less time preparing for my classes and more time composing.

Another problem was that as a serious composer, I wasn’t terribly comfortable in the academic avant-garde scene. Even though Juilliard wasn’t a particularly avant-garde place, my personality as a composer is very melodic and lyrical, unmathematical and unthorny. I felt it would be good for me to get out of the school scene and into a more commercial scene, not to make money but to work in fields which weren’t so dogmatic. In retrospect, it seems like a wise move. I’m writing the music I want to write, and I’m enjoying what I do.

###

At a prior PDQ Bach concert at the SF Opera House, we all noticed a lot of sirens, but the percussionists were not playing them. When the show was over we went out to the lobby to see the entire street lined with burning police cars and people fighting with the police. It was what would be later called the Dan White Night Riot! We went back into the theater and exited through the rear, getting away as quickly as possible... https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_Night_riots